Baldwin opened his eyes and saw an unfamiliar living room. A giant television, a glass case filled with cat figurines. A large painting of a woman wearing a beatific smile and a floppy hat. The boy, Newby’s boy, sitting on the orange rug and staring at him, still clutching that freaky toy.

Baldwin closed his eyes.

There was the Saddle Bar, the Cowboy Bar, and then the Big Tex. He remembered holding a drink, leaning up against a shining jukebox playing Dolly Parton’s “Jolene.” He remembered talking and talking. He could picture Newby’s face, brow furrowed, listening. Then: nothing. A blackout, for the love of Jesus Christ Our Lord, the first one in a year. Baldwin turned onto his back, pressed his fingers into his eye sockets. Seemed Katherine had been right after all, that bitch. He wondered how she was.

A burning smell made him start and look around. The kid was sitting closer now, a piece of toast held out like an offering on a china plate. “Thanks,” said Baldwin, sitting up. Pain sliced his brain clear through.

Not surprisingly, the kid didn’t answer. What in the hell was wrong with him? Baldwin felt a welling sorrow. Something awful had happened, or was about to. He chewed the toast and tried to shake off the familiar dread. “It’s chemical,” he told himself. That was what Katherine had always told him the morning after a bender. “It’s chemical,” she’d whisper, kneading his shoulders like dough. “Everything is fine. Nothing bad’s going to happen, baby.” Until she gave it up herself and spent the mornings cleaning, banging the pots around just to irk him and letting the kid scream.

“My Pop-Tart?” said Newby’s boy.

“Sorry?” said Baldwin.

The kid said it again: “My Pop-Tart?”

It was a question, that was clear, though Baldwin wasn’t sure he was making out the syllables correctly. Maybe the kid called his father Pop.

Baldwin ventured, “Where is your pop? He’s here?” Baldwin had a sudden vision—or was it a memory? A glittering house, decked out for the holidays. Newby, sitting next to him in a truck, staring at the strings of light through narrowed eyes.

“No! Pop-Tart!” cried the boy, and he got up and ran into a back room, slamming the door. The square-headed doll grinned at Baldwin maniacally. From behind the door, music started up. It sounded like the boy was playing some sort of electronic keyboard.

Baldwin took a breath. He stood and made his way to an unattractive kitchen. “Newby?” he called nervously. There was no answer, just the unnerving sound of a bass-heavy background beat. On the kitchen counter, an empty whiskey bottle rested next to two cups from McDonald’s, both featuring a character with a head like a hamburger.

“Oh, Christ,” thought Baldwin, “what have I done?”

This had happened to him before. Once, when he woke up fuzzy and Katherine was gone, he thought he’d killed her. They were living in Alabama, and the work was hell. There wasn’t even a bar in the godforsaken town, so he and some worms bought some rye and hung around in the parking lot of a Ramada. One thing led to another, and Baldwin woke up in the trailer he’d rented for the season, dry-mouthed and certain he’d ruined his life.

There was no memory of violence, only a thought that solidified as the day went on and the heat grew stronger. He searched every room, the yard, and, finally, underneath the trailer, expecting to see her long fingers poking out from the sludge, her hair wrapped around her neck, blue eyes blank and lifeless.

He’d been on the verge of calling the police when she’d pulled up in a taxi, arms full of Bugles corn chips and juice. She was pregnant then, just starting to show. “Oh, Clay,” she’d said. And now suddenly he yearned for her so intensely that he picked up Newby’s cordless phone and dialed.

He knew the number by heart. He knew the house and some of the furniture too. He knew the refrigerator and what was probably inside: Diet Coke, cheese, hot dogs for the boy. The ringing stopped, and Katherine’s voice said, “Hello?” Baldwin felt dizzy, and he reached out for one of the hamburger-head cups, drank the dregs down.

“Hel-lo?” she repeated.

“K-girl,” said Baldwin.

“Oh, you,” she said. And after a minute, “What is it this time?”

Rage rose in him, hot and bilious. “Why do you always—” he began.

“Save it, Clay,” she said. “Did you want something, or you just got a case of the dreads?”

“Katherine,” he tried.

“Check’s late again,” she said, flatly.

The thumping bass line continued from the boy’s room. Now there was a high-pitched voice as well, an off-key, eerie falsetto. Where the hell was Newby? And wasn’t there a wife in the picture?

“I’m calling from Twin Wells.”

“Twin Wells?” asked Katherine.

“Texas. It’s a small town . . .” Baldwin trailed off, not sure of what else to say. He tried to think of some words that could cover the distance back to Mississippi.

“Will you hold on?” said Katherine. “There’s somebody at the door. Here, talk to your son.”

Baldwin heard the phone change hands and then the boy’s nervous breath. “Well, hello there!” Baldwin said. In his own false cheer, he heard his father’s failings.

“That’s all,” said the boy, and the line went dead.

Baldwin held the phone to his ear. It had a pleasing shape and was cool in his palm. The buttons were long and flat. He traced them with his nose. After a while he went to Newby’s boy’s room and turned the knob.

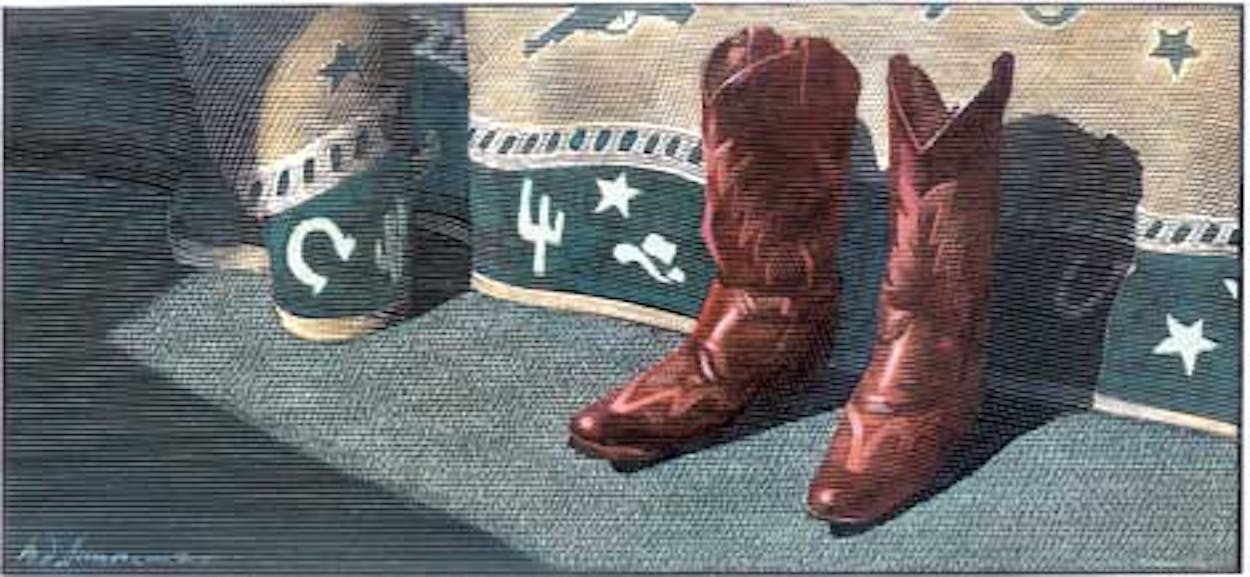

The kid was asleep on a fancy four-poster bed. A Casio keyboard was perched in the corner, next to a drum set and a pinball machine. There were toys scattered around, Legos and plastic swords and some things still in their colorful boxes. The boy’s breath was even and slow. Baldwin slipped the red boots from his feet and placed them carefully on the carpet. In the adjoining bathroom, a dressing table with a padded stool was jammed underneath a window that looked out on an empty clothesline. The table was cluttered with perfume bottles, a few photographs, and a Christmas card. Baldwin picked it up. On the front was a picture of Alexander Johnson III flanked by three children in holiday pajamas and a wife with hair like a large hat. Inside, someone had written in red pen: “I AM TRULY SORRY BUT YOU SHOULD HAVE KNOWN. SALLY.”

Outside on the porch Baldwin found a chair and a table, a pack of Winstons, matches from some place called the Warwick, and an ash-tray. He watched the afternoon fade to evening. Something awful had happened, or was about to.

The boy opened the door and came outside at about the same time headlights flashed in the distance. There was only one chair, so the boy stood. A truck approached, parking in the driveway. The driver cut the engine and climbed out. It was Newby. In the waning light, his face looked lined and tired. “It’s done,” he said.

He reached back into the truck and brought out a small handful of jewelry. An emerald pendant caught the light of the setting sun.