For Grandmother, it was always, “Next year, we’ll move him to Laredo.”

When my abuelo Leonides Lopez died, in July 1935, his expeditious summer burial in Tío Jose’s family plot in Cotulla was meant to be only a brief earthen sojourn. In the Cotulla summer heat, it was important to get the difunto into the ground quickly, after lying in state overnight in the family home.

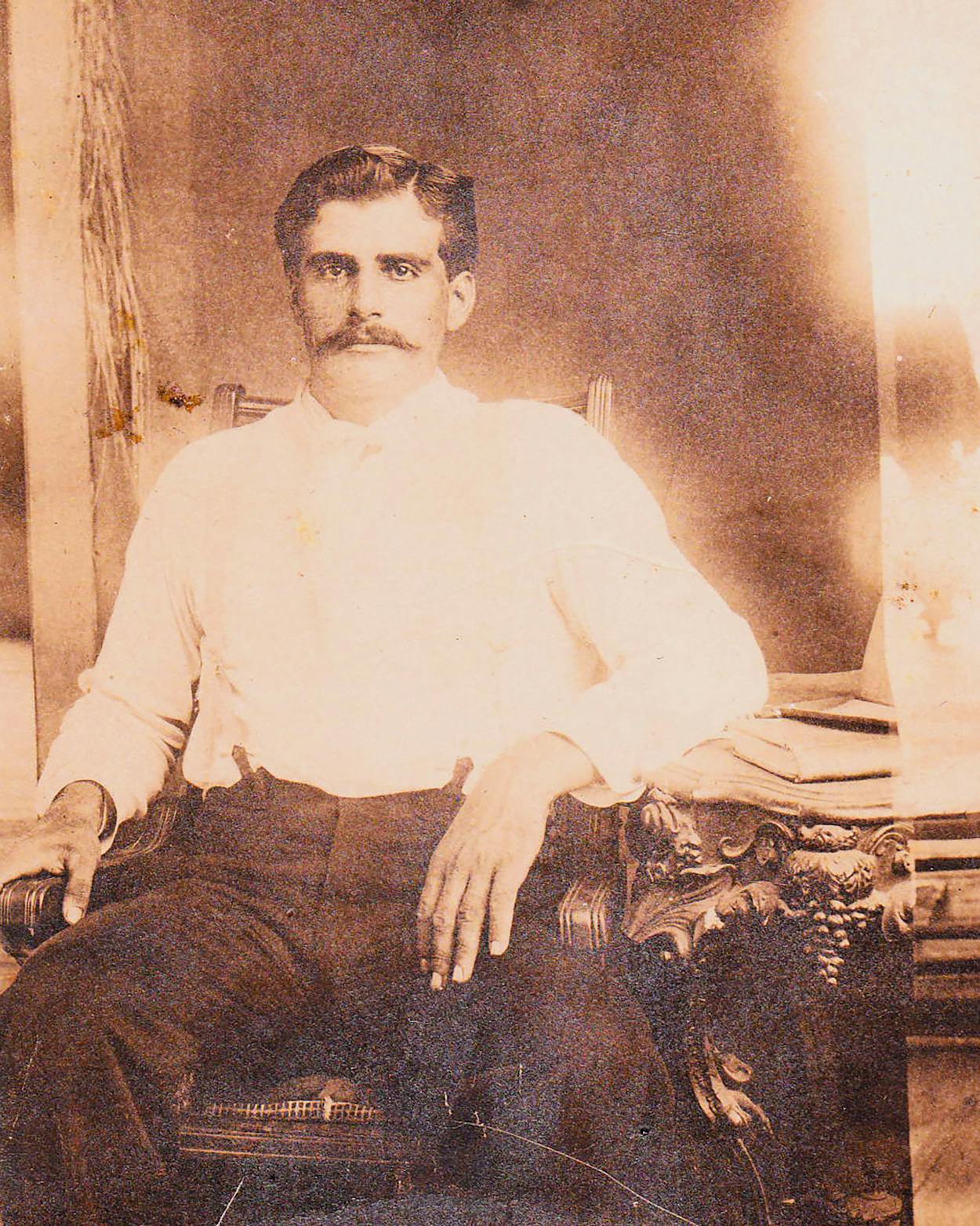

There are few surviving photos of Abuelo Leonides, none from his childhood or youth. In one studio portrait from 1908, sepia tinted, full of shadows and glowing orbs, he’s a vital young man, seated with one strong arm leaning on an ornately carved desk, a pen and notebook alongside an oil lamp. Broad-shouldered, he wears a white shirt with suspenders and black pants. One long muscular hand rests calmly on his lap as he gazes with a distant, pensive expression into the camera. With his dark features, wavy black hair, handlebar mustache, and penetrating eyes he looks almost like a Tejano Emiliano Zapata.

His funeral was one of the grandest for a Mexican that anyone had ever seen. And despite the fact that he was a Mason, and as such would ordinarily have been excluded from a funeral mass, Grandmother exerted her considerable powers of persuasion upon the priest to allow Leonides to receive a full religious funeral, which was attended by Mexicanos and Anglos alike.

Grandmother’s plan had been to transfer his body soon afterward to her family’s grander plot in the oldest cemetery in Laredo. Grandmother had never loved Cotulla, and she would not abide Leonides’ spending eternity there, even if it had been his home for most of his 52 years. This would happen as soon as possible after dispatching the business of closing Leonides’s grocery store, securing leases for the other properties in the town, and moving her children to San Antonio.

Even into the afterlife, Abuelo Leonides carried his orphan’s destiny with him. It would be 1954 before the plans were finally realized to disinter his bones from the Cotulla earth and transport them an hour to the south, to Leonides’s last repose, on the border with Mexico, just a few miles north of the Río Bravo.

Life in San Antonio had been very demanding for the widowed mother of five, with children ranging in age from nine to twenty.

Grandmother would not allow the children who were still in school to be sent to San Antonio’s segregated Mexican schools. My mother walked out of one such school on the city’s South Side. The two oldest boys, Leo and Lauro, were already teenagers. For them, the city’s always festive, brassy Mexican nightlife, with its boundless pageant of feminine beauty, was an invigorating change from Cotulla’s sleepy twilights and early bedtime.

Uncle Leo showed a predilection and a talent for card games. Uncle Lauro, tall, dark, suave, and already carrying an elegant, lonely air of being from far elsewhere, was more inclined to adoring las chicas Bejareñas. Grandmother watched her two eldest sons particularly closely, passing judgment on any alliances she deemed unsavory, whether among conspirators or romantic aspirantes.

But Grandmother’s lengthy delay in arranging Abuelo Leonides’s encore funeral may also have been occasioned by something that took place just after his death. A month after his funeral in Cotulla, there was a knock at the door in the early evening.

“Buenas noches, Doña Leandra.”

Grandmother received a lady visitor into the salon amid stacked boxes that were already being packed for the move to San Antonio before the beginning of the new school year.

My mother, always curious, told me how she overheard their conversation from a room next door.

“You do not know me, Señora Leandra. My name is Gertrudis Ramos. Forgive me for coming sin aviso.”

The woman was younger, perhaps in her late thirties, and Grandmother’s patience was already straining under the burdens of all the tasks of moving. She turned another lamp light on to have a closer look at the woman.

“What may I do for you, madame?”

“Forgive me, but I was very close to Don Leonides, señora.”

Grandmother then stared icily at Gertrudis Ramos, who had started to weep.

“What?”

“We were very close, Señora Leandra.”

“What do you mean by that, madame? My husband was a friend of everyone here.”

“Señora, he is the father of my daughter, Segunda.”

Grandmother let out a shriek, standing up.

“What did you say? ¿Que me dijiste? ¡Sinvergüenza! How dare you?”

“He loved Segunda very much. She’s three years old now.”

“Segunda? How many do you have?”

“Tengo solamente ella. Pobrecita. She is named after Leonides’s mamá—por eso, Segunda.”

The room went quiet for a while. Finally Grandmother moved toward the front door.

“I don’t care why you came here, and I don’t care what cuentos you tell about your daughter. He made no mention of these mentiras, if you’re coming to see if he put you in his will. I never want to see you again.”

The woman left without protest.

Mother always kept track of Señora Ramos and Segunda, the child who was her alleged half sister. Eventually they too moved to San Antonio, and Segunda went to the same high school as my mother, later marrying a pharmacist friend of hers.

Did she think the story of Abuelo Leonides’ second family was true?

Mother remembered the many nights Abuelo would set out in the evenings after dinner, dressed in a suit and a freshly ironed shirt, to sleep out on their little ranch, he said, coming back in the morning. That’s just the way things were.

And Segunda?

“Well, she really looked a lot like us,” Mother observed, grinning. “But we never mentioned it to each other. And she died a few years ago.”

This revelation may well have taken some of the urgency out of Grandmother’s desire to move Leonides’s bones to the family pantheon in Laredo. Let him pass a little bit of eternity there in the dry, knotty earth under infernal Cotulla. For a while, he was forgotten amid the new life in San Antonio.

Nearly twenty years later, it was two of “the boys”—Lauro and the youngest, Lico—back from the war and out of the Army, who pushed for their father to be taken on his last journey to Laredo. Grandmother went along with it, but my uncles found the Mexican gravediggers in Cotulla who would retrieve Abuelo from his sleep in the Cotulla tierra and then take him to Laredo, where they would dig his new tumba in the cemetery where Grandmother’s parents rested and where Grandmother would find her last repose.

A priest would await them all in Laredo, to readminister the sacred rite of extreme unction, which is ordinarily performed before death. Instead, by order of Leandra, it would now precede Abuelo’s second burial. Grandmother had insisted on this in light of what she had learned after Leonides’s death, and she wanted it done regardless of the theological objections or sacramental casuistry.

He had received final blessings once before, back in 1935, but she didn’t want to risk that he hadn’t repented himself of his shameful secret child before dying. So the despedida blessing of penance was reprised.

She would do Leonides that one last kindness.

Near the end of the century, I was in Laredo with my mother and Lopez cousins visiting from Maryland.

Robert Lopez was the younger son of my uncle Leo, a longtime radio deejay in Baltimore using the on-air name Lopez, doing the morning news and hosting a weekend program aptly called The Spanish Inquisition. I had always told him he was our walking cultural experiment, a Mexican raised in captivity, away from the environs of ancient Tejas. Uncle Leo and Aunt Lola had moved to Maryland in the fifties, partly to escape the disapproval of their families at what was then a controversial mixed marriage between a Mexican man and an Anglo woman. Never mind that both were Texas-born Americans.

In the years before, Bob had begun to make trips to San Antonio, as I put it to him, “in search of his awakening inner Mexican.”

“I’m half Mexican,” Bob reminded me. “My mom’s a Cherokee German.”

Of all my brothers and seventeen Lopez cousins, Bob was the first to begin wondering with me about the origins of our family story, even though he had grown up so far from the homelands. On this trip he was with his wife, Jean, and their ten-year-old daughter, Leandra, who was making her first trip to the ancestral homelands. Though Jean was very fair and Bob light-complexioned, Leandra had been born with the dark-eyed, morena Lopez look, and she delighted immediately in the curious Mexican world of San Antonio. She was the second child in the family to be named after Grandmother. The day before our trip to Laredo, we went to Kallison’s, an old Western wear emporium in the city’s downtown, and bought Leandra her first pair of cowboy boots, brown and pointy-toed, with curlicued pink thread piping decorating the shaft.

In Nuevo Laredo, on the Mexican side of the border across from Laredo, Leandra accompanied me to one of the noisy, parti-color wooden shoeshine stands with bright-red awnings in the plaza.

With norteño tunes blaring from a battered red transistor radio, two chamacos began the elaborate choreography of a proper frontera shine, starting with a vigorous terry-cloth wipe, rubbing in the shine paste, proceeding to first buffing, complete with back-and-forth samba dance steps, then twirls, before unleashing a battery of air guitar flourishes to daub the boots with cream, rubbing that in, then another buff, culminating in the signature technique of passing a flaming torch over the shoe of the boots, “para que se brillen bien,” one of the kids said, smiling up at us with two gold front teeth.

Leandra watched it all with an elegant bemusement. Puro Lopez.

Having a late lunch at the Rincón del Viejo, Nuevo Laredo’s famous mecca of roasted cabrito, the regional delicacy of charcoal-broiled young goat, we ate outside on the restaurant’s patio on a temperate afternoon in the spring. A shopping cart rattled out of the kitchen, heading across the courtyard toward the rustic grill shack. It was piled perilously high with an unwieldy heap of cleaned and skinned cabritos, still dripping from their overnight marinating in spiced milk, as they were prepared for the coming evening’s legion of diners. In an instant, Leandra grabbed the family video camera from the table and ran out in front of the cart of carcasses so that she could shoot its approach. She held out her hand, and the grinning kitchen porter stopped and let her get close-ups of some of the skulls, containing my mother’s favorite part of the cabrito, the brains.

She finished, the man continued to the grill with his cargo, and she came back to the table laughing, scrunching her face in mock disgust.

Very, very Lopez, we all agreed.

It was a very Lopez journey that day.

Earlier in the morning, we had stopped in Cotulla and found the badly aged and chipped stone bench in the town plaza where Leonides’s and Leandra’s names were still inscribed. On the seat, someone had scrawled “¡La EME Siempre!” the graffiti tag for the Mexican Mafia, a violent gang that has spread widely through the border region and cities with big Mexican populations.

Mother showed us the Welhausen Mexican school, where LBJ had taught for a year, making his students memorize Walt Whitman’s “O Captain! My Captain!” When we came to the place near the railroad tracks where the Lopez Grocery Store and home once stood, we found a vacant, overgrown lot.

In one spot, we thought we could still detect the lines of a broad foundation of a building, weathered over but still marking out a shape in the sand.

Mother pointed to a small hill where she said the porch of the house had stood. She remembered once when she had been given a silver dollar by her father and told she was not to lose it. Immediately, she tossed it into the air, laughing as it flipped and twinkled high above her, only to miss catching it; it landed instead somewhere in that fine straw-colored sand—and was never seen again.

“It just disappeared into the sand,” Mother recalled, “like it had never been here in the first place.”

After his death, Christopher Columbus’s bones were briefly buried in Valladolid, until they could be taken to the island of La Española, according to his wishes. After three years under the ground, he was moved to a crypt in a monastery in Sevilla. Eventually he was moved again, to Santo Domingo, but his remains were later sent to Cuba when the French took over the island, in 1795. The explorer was evicted once more, from Cuba in 1898, when the Spaniards were expelled, and then lost altogether until recently, when DNA testing confirmed his true whereabouts in a sepulchre within an ornate silver-encrusted chapel in Sevilla.

Hernán Cortés, El Gran Conquistador, died miserably of an intestinal infection and was buried in Sevilla in 1547. Nineteen years later, his bones were moved with great ceremony to Mexico City; then they were lost for more than a century, to be only recently rediscovered. Maybe this was some part of the destiny of Spanish pioneers in the New World, after a lifetime of wandering and displacement, to spend eternity looking for a final resting place.

It was in the Christmastime of 1954 when, after being dead nineteen years, Abuelo Leonides finally took his last drive down the highway from Cotulla to Laredo in the back of a battered pickup truck.