The movie would have to open with a shot of Jackson Field, in Alpine, home of the Sul Ross State University Lobos. Built in 1929 and having seen little touch-up since, the rock-walled stadium would give an instant feel for what it means to play small-college football in a West Texas ranching town. Narrow stacks of metal bleachers face off on either side of the gridiron, but there’s no horseshoe seating behind the goalposts, just practice fields, a few rooftops, then long stretches of scrubby desert floor. An ancient press box sits atop the home-side stands, its Plexiglas windows bowed and yellowed, with busy train tracks running just twenty yards behind it. In the film’s opening moments, an old freight train could roll by the field, hinting at a resilient power ignoring the passage of time. If the scene were filmed after a rare rainy period, as Alpine experienced in 2007, the hills around the stadium would be unbelievably green, implying a sense of renewal and rebirth. If by the time of filming the regular drought had returned, the verdant effect could be created in the editing room. Reality can never be allowed to interfere with the telling of a good story.

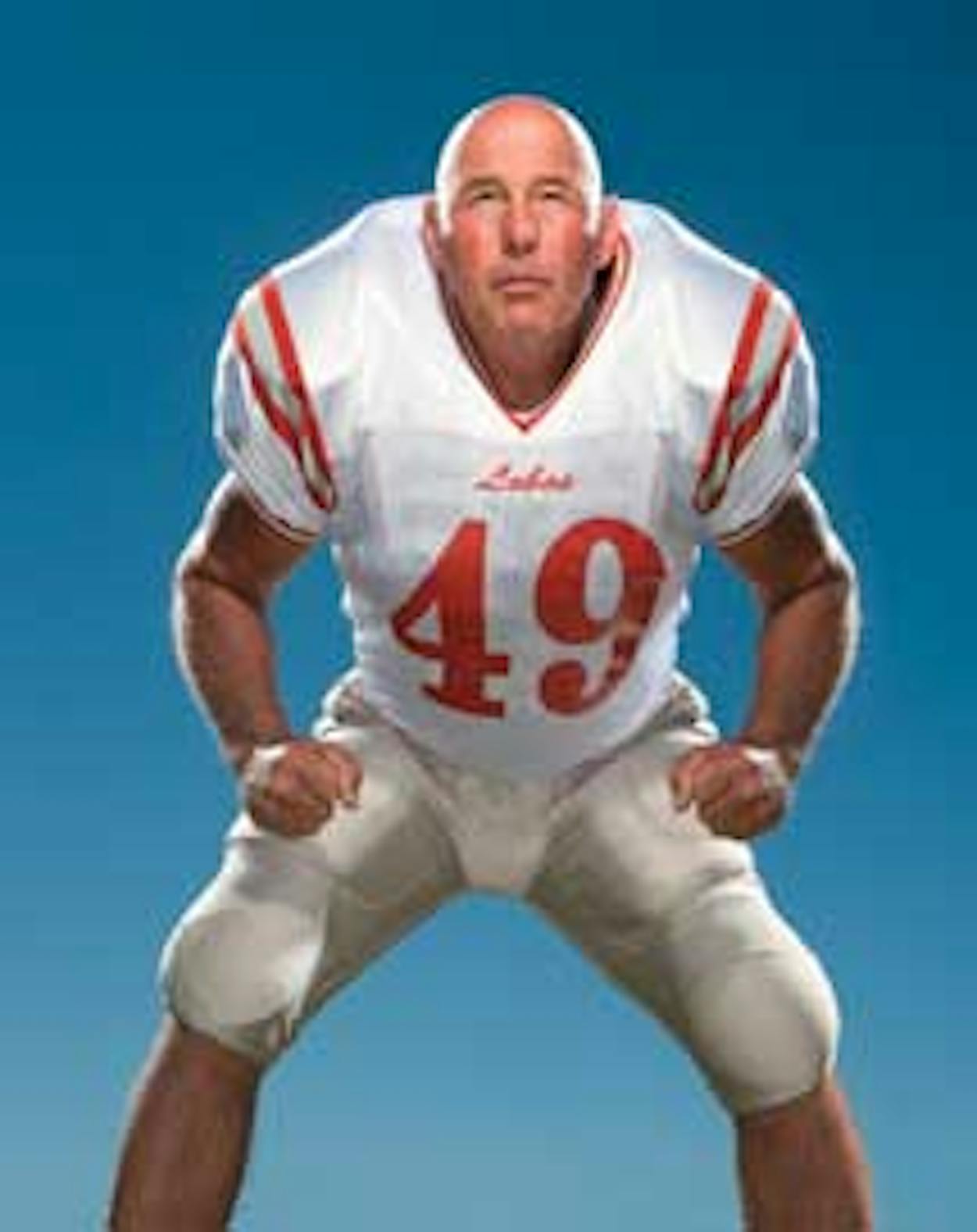

Set the scene at a practice. Since Mike Flynt didn’t see action at linebacker until the season’s final game, make it the Friday workout before that last contest, a home game against Mississippi College. Script it as much like that real November afternoon as possible: The players stroll onto the field in bunches, dressed in red shorts and jerseys, no pads, most carrying their beat-up gray helmets with the bar-SR-bar logo. Flynt stands out, but not because he’s forty years older than his teammates. At five nine he’s a little short, but his barrel chest, reputedly still capable of bench-pressing four hundred pounds, dwarfs everyone else’s, and his sleeves are bunched above better-defined biceps. His helmet never comes off, a nod to the old-school virtue of always being ready to go into the game.

Shots of other players reveal a ragtag bunch that couldn’t have played anywhere else, the Bad News Bears of Division III football. They’re all shapes and sizes, the tall and the short, the ripped and the rippled. Their mood is loose, and the trash talk is constant. Though their playoff dreams dissolved with a week-eight homecoming loss, they still hope for a victory on Saturday to cement a winning 6-4 record, an impressive feat for a team that played six games on the road. Finishing with a win would mean even more to the team’s seniors, most of whom—except Flynt, of course—have recently endured winless seasons at Sul Ross.

The comic relief comes from head coach Steve Wright. As the players assemble, he lounges on a sofa on the sideline. One of his players points out that at least he’s not chipping golf balls or lying at midfield talking on his cell phone, as he often is. After some brief words of inspiration, Wright sends the team off by position for drills, but the camera stays with him as he heads for a goalpost to visit with alumni and journalists. In his Smoky Mountain drawl—his “y’alls” sounding like “y’owls”—he tells them how unusual their presence is at a frontier program like Sul Ross. Traditionally, reporters and alums have been scarce even at Lobos games, forget Lobos practices.

Mike Flynt has changed all that, Wright tells the reporters. Big media outlets from all over the country have looked in on Alpine this season—CBS, NBC, ABC, Fox News, ESPN, the Los Angeles Times, Sports Illustrated. There have been movie and book offers by the dozens, blog posts and radio interviews in the hundreds. Flynt has even been writing a weekly column for the Associated Press. It’s been a strange autumn.

The camera finds Flynt. He’s jogging across the field with the linebackers, and by his gait you can tell he’s still a player—up on his toes, with his elbows in and his fists high and together like a boxer’s. Instead of pumping his arms, he swings them slightly side to side, as if he’s conserving his energy in case the chance comes to cream someone. He stops with his group to practice intercepting passes, and his voice can be heard over everyone else’s. “Attaboy, Milo!” “Good hands, Nate!” “That’s it, Kyle!” And then, when he takes his turn, his teammates give back. “Nice job, Mike!”

But some moment in this scene will have to explain why Flynt’s here. Maybe now he turns to a teammate and repeats the line he’s told reporters and players all year, that he has come back to right an old wrong, to make up for having been booted from Sul Ross for fighting during two-a-days in 1971. Have him add his invariable reality check, that though his aging body has kept him from contributing on the field the way he’d hoped, being teammate to these young men has been reward enough. But one thing will need to be made absolutely clear, maybe by having Flynt squint his green eyes at a tailback goofing near midfield, juking in and out of stationary teammates: Flynt has returned to Sul Ross to play linebacker, and tomorrow’s game will be his final opportunity to make one last big play, to deliver one last good hit.

The scene should probably end there, though if the movie were to depict the whole of that day, it would have to keep rolling through a curious moment after practice. As the players retired to the field house, two of the team leaders, seniors Austin Davidson, the school’s all-time leading passer, and his best friend, Zach Gideon, a giant defensive tackle with a mohawk and perfect nickname, Giddy, lingered on the field for a field goal—kicking contest. They made a ridiculous sight, the pretty-boy blond quarterback versus the hulking lineman, who finally won the battle with a straight-on toe kick from 25 yards.

Afterward, they talked about their years at Sul Ross, the fun they’d had playing despite all the losses, their readiness to get their degrees and get on with their lives, and Flynt.

“Mike’s a great guy,” began Giddy, “and if this brings attention to the program, that’ll be great. But we’ve got nine seniors on this team, and he’s the only one that anyone notices.”

“Nothing’s about us or anything we’ve done,” said Davidson.

Giddy paused, then added, “Mike’s first day on scout defense was at the second-to-last practice. He’s not contributing to the team. He’s only worried about getting a movie deal.”

That’s probably not a scene that would make it into the film. It’s a little too sour—and too self-conscious—for a feel-good sports flick. It’s also not a sentiment expressed by any of the other players I spoke with in the three months I followed the Lobos last season. Every one of them talked about the inspiration of seeing someone Flynt’s age survive two-a-days without ever once complaining. These late gripes sounded like the envy you might expect from kids ending their playing days in a newcomer’s shadow. There’d be no place for something like that in a movie about Mike Flynt.

The legend of Mike Flynt begins in Odessa, where his family moved from Mississippi when he was three years old. His father was a World War II vet who’d fought at the Battle of the Bulge, one of the few soldiers in his company to make it out of the Ardennes. Toughness mattered to J. V. Flynt, and he instilled it in his only son, a small kid, by teaching him early to never shy from physical confrontation. From the time Mike could hold up a pair of boxing gloves, his dad would get on his knees in their living room and they’d spar. Mike came to live by the lesson of those encounters: “There is no sin in getting whipped. The sin is in not fighting.”

The football field was the first place where he would distinguish himself, though it took a little time. As an eleventh-grader, he played sparingly on defense for the Odessa Permian JV team. But the next year, 1965, Coach Gene Mayfield took over the varsity squad and opened up the depth chart; every player would have to earn his starting spot. Flynt, already a dedicated weight lifter, busted his ass to impress the new coach. He went with the varsity players on unsupervised training trips to run in the nearby sand hills. He made first team offensive back, one more scrappy oil patch kid on a legendary squad that would go undefeated and win the school’s first state championship. It was the birth of the Mojo dynasty. Mike made all-district.

After graduation, he passed on chances to play at the University of Arkansas and Sul Ross to follow a girl. He ended up at Ranger Junior College, 85 miles west of Fort Worth. When neither the girl nor Ranger football nor a subsequent semester at Fayetteville worked out, Flynt wound up back home in late 1967. His football career apparently over, he began to make a name for himself as a bar fighter.

“It wasn’t something I broadcast,” he told me. “But people coming into Odessa knew me one of two ways. Either ‘Flynt played football here,’ or ‘There’s that ass-kicker.’ And then it’s a fastest-gun-in-the-West-type thing. Somebody wants to be talked about more favorably than you.”

The fights weren’t limited to punching and kicking. “It was chairs, pool cues, gouging . . . all of those. It was winning.” Before too long, word made it to Alpine that Flynt, that old Permian standout, was living in Odessa and not playing football. The Sul Ross coaches gave him a scholarship to come play for the Lobos.

In those days Sul Ross competed in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics’ Lone Star Conference, a powerhouse akin to baseball’s Negro Leagues. Since the Southwest Conference was still effectively segregated, the best black athletes in Texas played in the Lone Star. It was no minor league. From 1967 until 1973, the Lone Star’s two dominant teams, Texas A&I and East Texas State, had twenty players drafted by the NFL and the AFL. And beginning in 1969, Flynt’s first season at Sul Ross, a Lone Star school would win the NAIA football championship every year until 1979. But Sul Ross wasn’t one of them. It was the conference stepchild. Where every other school had a natural geographical area for recruiting, the Lobos were out in six-man country, where the few local recruits didn’t rate with the other schools’ and imports typically came because they couldn’t start anywhere else. Sul Ross made its way by being a little bit tougher, hitting a little harder. Flynt fit right in.

A natural leader, he’d take guys into the weight room and organize informal track meets on Jackson Field, just like he had at Permian. He was a second-string defensive back when the 1969 season opened, but by the fifth game he was starting at outside linebacker, and he proved to be a terror in the Lobos mold. Before an East Texas State game, Coach Richard Harvey had instructed the defense to neutralize the opposing quarterback, a brilliant passer named Dietz who was considered a showboat for wearing white shoes. At the end of a long scramble with Flynt in pursuit, Dietz turned and smiled as he stepped out-of-bounds. Flynt laid him out anyway, explaining to Coach Harvey later, “If I’m going to run that far, I’m going to hit somebody.” Sul Ross finished a disappointing 4-5-1, but the season did feature the single greatest moment in Lobos gridiron history, a bloody 13—12 homecoming victory over A&I. It would be the Javelinas’ only loss on their way to the national championship.

The Lobos started the 1970 season on fire, winning their first four games. An early highlight was a win against Tarleton State, in which Flynt recovered four fumbles and picked off a pass, earning conference Defensive Player of the Week honors. The next week they beat seventh-ranked Sam Houston State, in Huntsville, a game made famous after the Lobos’ bus broke down ten miles outside town. The players had to hitchhike to the stadium, trickling onto the field in groups of three and four until just before the coin toss. They went on to win 50—18, then the next week beat fourth-ranked Howard Payne, 31—21. The Alpine City Council declared 1970 “the Year of the Lobos.”

But the season turned south the following week, when A&I avenged the ’69 upset with a 27—0 thumping. The Lobos then dropped two of its next three, to McMurry and East Texas, before closing the season with two wins for a 7-3 record and a tie for third place. Flynt made honorable mention all-conference, won team awards as most conscientious player and a defensive standout, and was named a team captain.

By then he was known all over campus. A good-looking kid with a great shock of brown hair, he was considered not a kicker but a cat daddy for his snappy dress. But he had also cultivated his fighter’s reputation in Alpine. If the phone in the athletic dorm, Fletcher Hall, rang on a Sunday morning, the players assumed the caller was the sheriff and that he was probably looking for Flynt. In early 1971, there was a famous fight in the all-night truck stop cafe just outside town, followed by a trial that was well attended by Lobos and locals. Flynt and his roommate, Randy Wilson, were fined $100, and the team was banned from the cafe.

Flynt didn’t participate in spring football workouts but was back with the team for two-a-days in August. And like a lot of Lobos, he was hoping to turn the previous year’s success into a conference championship. But then came the fight that got him kicked out of Sul Ross. Last year’s newspaper stories called it “one fight too many.” Flynt calls it the great travesty of his life.

His comeback was born over beers at a Lobos reunion in San Antonio last summer. When a former teammate said that Flynt’s dismissal had killed bright hopes for the ’71 season, Flynt said he had never forgiven himself for letting the team down. Randy Wilson, still Flynt’s best friend, suggested he do something about it, and within days Flynt had phoned a former coach to inquire about eligibility. He discovered, to his surprise, that according to Division III rules, he could still play, but there would be administrative hurdles to doing it anywhere but Sul Ross. That was irrelevant to Flynt. “There was no consideration of doing this somewhere else.”

We were talking in the student center cafeteria on campus, where we visited periodically through the season. Still dressed like a cool kid in tight T-shirts, loose jeans, and cross trainers, he was impossibly solidly built, his head shaved clean and colored deep red from the Indian summer sun. The media spotlight had restored him to “big man on campus” status, and students walking by interrupted to wish him luck. They’d read the stories and knew him as that old guy on the football team. Used to be a troublemaker. Went on to be a strength coach at Nebraska, Oregon, and Texas A&M. Dabbled successfully in oil wells and gold mines. Had spent his recent years in Tennessee, selling a fitness device he’d invented called Powerbase.

He was soft-spoken, nothing like the mean-ass of legend. “I’ve had people tell me I’m the most changed person they’ve ever known,” he said the first time we talked. “I always hope that’s because they can see God and Christ in me, not through me preaching but through things that I do. And things that I don’t.”

When he decided to return, there were only a few weeks remaining before practice started. “I drove to Alpine,” Flynt said, “met with Coach Wright, and went out and ran with the freshmen. He watched me and saw that I could run with them. He said he was expecting chaos but that I blended.”

Flynt and his wife, Eileen, quickly sold their home outside Nashville and moved to Alpine, where he reenrolled at Sul Ross, signing up for History of American Sports, Health in Public Schools, and Seminar in Management. He changed up his training regimen to get into football shape. He ran sprints twice daily. He concentrated on explosive lifting in the weight room, medium weight with intense reps. After sweating through two-a-days in the blistering August heat, he made the team.

Where to play him was a problem. He had strength, size, and speed, but his lateral movement was lacking. Coach Wright said that in a 10-yard square, Flynt would be fine, but with more room to cover, he’d be a liability. Wright listed him at linebacker, but far down on the depth chart.

Then there was the matter of injuries. In the first weeks of practice Flynt suffered a stinger, tore an arch, discovered two bulging vertebrae, and pulled a calf and abdominal muscle. He learned quickly that his body didn’t recover like a young man’s. He spent much of his time at practice alone, high-stepping on the sidelines to keep his muscles warm in case a coach put him into a scrimmage.

But there were things he could do that the young bucks couldn’t. At a weight-lifting session, the coaches called two offensive linemen and Flynt to the middle of the room for a contest. They’d each lie on the floor and bench-press a 45-pound disk as many times as they could. The last one to stop would win. With the whole team circled around them, Flynt looked up and saw only one face, a player he’d met during two-a-days, with whom he’d discussed the power of Christ. “It was like God saying, ‘Okay, Mike, you can do this.’” Flynt asked the kid to say a prayer for him, then shut his eyes and started lifting. “I was thinking the whole time, this is such a blessing. I opened my eyes, and the guy on one side had stopped and the guy on the other was slowing down. I knew I had it won.”

The feeling was sweet, but it didn’t get Flynt any closer to the field. As a coach said later, bench-pressing talent only matters when you’re on your back, which is not where you want to be in a game. Flynt didn’t even travel to the first two games, a gutsy rally to win against Texas Lutheran, in Seguin, and a blowout over Southwest Assemblies of God, in Waxahachie. He suited up but didn’t play in the third game, a 55—14 loss to fourth-ranked Mary Hardin-Baylor that could have been a lot worse. (The Crusaders returned the opening kickoff for a touchdown and led 21—0 after barely three minutes of play.) Between the runaway loss, the national news crews, and the MHB band chanting, “We want Mike!” the game turned into a circus. Lobos alums in attendance were livid at Coach Wright for not playing Flynt in a game that had gotten far out of hand.

None of them knew that his injuries had already caused him to reimagine his dream. After standing on the sidelines during another lopsided loss, to East Texas Baptist at home, Flynt explained, “Initially I had visions of being a starter. But I’m not good enough. I see myself now in a support role, playing on special teams, giving guys a break when it’s hot, being their friend and teammate and keeping them motivated and focused on what we need to do to win.”

As he talked about the off-the-field aspect of his quest, he began to sound less like an old warrior and more like a modern businessman. “I never thought about the number of people that would be so interested and captivated by what I am doing,” he said. “And inspired. Gosh, I’ve gotten so many encouraging e-mails and phone calls about how I’m changing lives. But at the same time, I’m inundated. Book deals. Movie producers chomping at the bit. Some came in and met with the school president, Coach Wright, and me. They said there was going to be a writers’ strike and we needed to get this done. I told them, ‘I can’t sign anything right now. I’m not going to jeopardize my eligibility.’”

He stressed that there would be no deals until the season was over. He was distinctly aware that what Hollywood wanted were details about his past, specifically about the fight that had gotten him kicked out of school. But he intended to keep that card close to his chest. “I was told that when the AP story ran, my life became public domain,” he told me, referring to the first in-depth article written about him during the historic season. “That if somebody wanted to make a movie or a book out of my life, they could, without my cooperation. From a business standpoint, if Texas Monthly delves into my past, what’s to prevent you from selling that to someone who wants to do a movie?

“The story for me is about now. It’s Sul Ross and my teammates and Coach Wright and the sacrifices he makes to do what he does. That’s what has value to me.”

Steve Wright looks exactly like a 51-year-old football coach running a modestly successful program in a small town. His bowl-cut blond hair spills in a mess out over a white visor bearing the school’s logo. His lean, sturdy bowlegs hold up a pot belly clad in a wardrobe of only school colors. He projects a slightly beleaguered but ever-upbeat quality, though you won’t get much sense of this by looking into his eyes. They’re hidden behind heavy lids and wire-rimmed glasses, and when he’s talking about serious matters requiring serious contemplation, they’re usually closed.

His statements are also tough to decipher. He talks like Sparky Anderson auditioning for the starring role in a Casey Stengel biopic. His rambling addresses open with “Folks . . .” whether he’s talking to fifty people or one. He’ll tell you that football is not just about “wons and losses” and insist that the Lobos’ winning season in 2006 “was not an abolition.”

So you figure him out not by listening but by watching. His mouth puckers round when he senses that you’re missing his point. It purses flat as he sees you starting to understand. And when he realizes he’s taught you something, it blooms into a gap-toothed, coach-that-ate-the-canary grin, his teeth covered with tobacco flakes, like he’s just napped for an hour with a pinch of snuff in his mouth. Typically the lesson is that what matters most is not what happens on the field but what you take with you when you leave it.

Like when he talks about losing his first 26 games as head coach of Sul Ross, beginning on opening day 2002. “You have to trick your human computer, your brain,” he said, sitting in his office on the Monday morning after the week-four loss, to East Texas Baptist. “The first game Austin Davidson played, we lost 79—14, at Richard Simmons,” he said, referring to the school that everyone else calls Hardin-Simmons University. “That’s a pretty good whipping. To get in the bus and try to get to practice and play the next game, yeah, there was a lot of soul-searching. But the trick in the belief was ‘We can get this done.’”

He fiddled with a paper clip while he spoke, eventually making perfect sense. “The low point was at the end of the second season. The next-to-last game. We were getting beat pretty handily, getting ready to go 0-9, which is actually 0-19. There’s about twenty people in the stands at the end of the game, and one of our kids makes a play by crawling. He gets blocked out of the play, gets his butt kicked, and then, as the other guy is running down the hash mark, our kid crawls and makes a shoestring tackle. And folks, there’s nobody there to see it, because we weren’t successful in people’s mind.

“I remember watching film that night, then going home and saying, ‘That’s a shame.’ So I went to the kid’s dorm, found him, brought him to my office, and made him watch it. And I told him, ‘This is one of the greatest plays I’ve ever seen, and you need to know someone appreciates it.’”

Coach Wright’s office befits the brain trust of an underfunded program. The cinder block walls are painted white. A space heater stands unplugged in the corner. A laptop sits on his cluttered desk. There’s a whiteboard with stick figures positioned in the Lobos’ 3-4 defense, a game ball commemorating his 1989 junior college national championship at Navarro College, and a D3Football.com Regional Coach of the Year plaque honoring the Lobos’ 5-4 finish in 2006. His most precious keepsakes are an Olan Mills portrait of his two daughters, Stephanie and Synthia, and a painting of a redbrick dormitory at Carson-Newman College, in Tennessee, where his grandfather was the school president for twenty years and his dad played football. In the painting, the ghosts of legendary Carson-Newman gridders are depicted running through the clouds above the dorm. “I’ve been offered five thousand dollars for that painting,” Wright told me. “I said, ‘Uh-uh, baby, no way.’”

Try to find his salary inside a $247,000-a-year program and you’ll see the sacrifice he made by keeping the painting. Only two of his seven assistants are full-time, and they all pull double or triple duty to augment their paychecks. The defensive secondary coach is the head of the school’s equine science department. One of the line coaches is a graduate assistant who leaves practice early on Wednesdays to play a weekly gig with his country band. The defensive coordinator washes uniforms after games.

His players are issued one helmet, one pair of shoes, and one set of pads for the season. Socks, jocks, and underwear are the kids’ responsibility. Much of that goes with being a small Division III program, where scholarships are prohibited. As Wright frequently points out, his Lobos are actually paying to play, and getting them to do it in Alpine is no easy task. “Folks, we’re two and a half hours from the nearest Super Wal-Mart,” Wright said. “So a lot of these guys recruit us. They call, and we’ll tell ’em, ‘Send us your film. Let’s see if you can play college football.’” He winds up with kids who learned about Sul Ross because an older brother played there or because one of their buddies is going there. “Hell, we’re all misfits here,” Wright explained, “even the coaches.”

None of the Lobos have dreams of playing on Sunday, so Wright emphasizes enjoying what football they have left. He keeps practices unbelievably relaxed. He doesn’t have a playbook, calling his improvisational offensive scheme “basketball on grass.” The result is a program based on the only cliché he’ll use. It may be the only one he can afford or, as he might joke, the only one he can remember: “These kids play because they love this game.”

He paused to look out his office door at a group of players waiting to turn in proof-of-attendance slips. “This may be the only place where this Mike Flynt deal could have happened,” Wright said. “A guy walked in, and yeah, he’s fifty-nine, and after listening to him, I felt, ‘If I do this, I’m stepping on loose branches, because it’s so unique.’ But to me, out here, it’s not unique. If he could physically do this, why not give him a chance?

“Mike’s got his rationale. He’s trying to right a wrong. Well, there’s a hidden thread to why I let him do it. My oldest daughter, Stephanie, has an undiagnosed autoimmune neuromuscular disease. That’s what they call it when they don’t know what it is. And having her be handicapped, at times, I’ve had firsthand experience with the limitations we put on folks, for a disability or gender or age.”

He lifted his visor and scratched his head, then shut his eyes. “But you know, my younger daughter, Synthia, was also affected. When the doctors came in to see Stephanie, they didn’t address Synthia. I’m not sure that wasn’t good practice for this Mike Flynt deal.”

His lips puckered. “There’s no doubt we have a story here that can benefit people. There’s no telling the synergistic multiplication effect that this exposure can have. But this is not a publicity stunt. Mike will not bump in front of those other kids for publicity. I will manage this through the program first and then each individual athlete, whether it’s Mike or Fernie Acosta or Milo Garza or one of those freshmen who hasn’t seen the field yet.”

He seemed to be saying that Flynt was just one of eighty players, no more or less important than any other. When I asked if that was what he meant, Coach Wright leaned back in his chair and grinned.

As the season progressed, alums eager to see Flynt play felt their frustration with Coach Wright fester, then mushroom. Each week the coach passed on uniquely fitting occasions to return Flynt to the field. The East Texas Baptist game had been the home opener, a chance for a triumphant return to Jackson Field, yet Flynt spent the afternoon rooting on the sidelines. The next week’s game, against Howard Payne University, in Brownwood, was attended by Flynt’s three kids, his year-old grandson, and his 82-year-old mother, a manager at the local Wal-Mart. Again, no Flynt. Though the contest was a double-overtime barn burner—won by the Lobos, 34—31, when Giddy blocked a field goal that would have sent the game to a third OT—the alums who rushed the field after the win weren’t looking to celebrate. One former teammate of Flynt’s found Wright in the end zone and took him apart, pointing a finger and saying, “Nobody cares about you. These people are here to see Mike. You’re squandering an opportunity to make history!”

Over the next two weeks—the Lobos’ bye week came next—Wright received scores of ass-chewings in thousand-word e-mails and half-hour voice messages. On an Internet message board set up by an alumni group called the Sul Ross Baby Boomers, commenters likened him to a jackass and demanded he be fired. Randy Wilson posted a message urging the Boomers to complain to the school, providing e-mail addresses for the athletic director and president. The two officials declined to tell Wright what to do, but they frequently inquired as to just what he was doing.

Flynt, however, had become even more aware of his physical limitations and had asked Coach Wright to let him take it easy in practice. He explained in his weekly AP column, “Coach wants me to do what I can in practice at what I feel like is an acceptable risk to my body. He doesn’t want me going 100 mph in practice then not being able to play Saturday. I really appreciate that.”

The strategy worked. In a week-six rematch with Texas Lutheran, after Davidson threw a long touchdown pass on the opening drive, Flynt sprinted onto the field with the extra-point team. In the stands, there was bedlam. Hugs and kisses rained on the Flynt family, and a Boomer giving play-by-play on his cell phone screamed himself hoarse trying to be heard over the crowd. But there was no time for wonderment down on the field. Flynt lined up at left end. With the snap and the kick, the kid across from him didn’t make much of a move, and Flynt just gave him a little touch. What the moment lacked in excitement it made up for in history. Three months shy of his sixtieth birthday, Mike Flynt was back in the game.

And he wasn’t finished. The game proved to be another shootout, with either the score tied or the lead changing hands fully thirteen times. As the scoring mounted, the extra points and field goals carried greater import, and eventually Flynt’s man was challenging him. Flynt answered every time, standing him up when he came out of his stance, then patting him on the butt when the play was over. When Lobos kicker Mike Van Wagner’s field goal clinched a win in the third overtime, 45—42, Flynt was on the field. He wrote for AP the next week that he’d felt like a kid again, then closed by explaining how much these young men meant to him. “Come to think of it,” he wrote, “that’s another part of the script that’s been better than I could’ve written it.”

When the homecoming game with Hardin-Simmons came two weeks later, Flynt had two games under his belt. The team was riding a three-game winning streak and eyeing the playoffs, and the unprecedented attention to Sul Ross guaranteed a monster turnout. Flynt’s old teammates arranged a reunion of the ’69 and ’70 squads, and some forty of them made the trip. They were introduced on the field before the game, where Flynt joined them to receive a gubernatorial proclamation. Then he returned to the field house to get ready to play, and his contemporaries found places in the stands.

They saw the Cowboys take an early 7—0 lead but quickly noted—between comments on how much better the grass looked now and how much bigger the players were—the fight in the ’07 Lobos. The defense stiffened, and Sul Ross scored a touchdown at the end of the first quarter. Flynt’s old teammates were so busy pointing at him when he lined up for the extra point that most didn’t notice that the kick missed wide right.

The lead seesawed back and forth, and Sul Ross was up 19—18 early in the second half when Flynt got the chance everyone was looking for. It was storybook perfect. The Lobos lined up for a field goal attempt directly in front of the alums, with Flynt on the end nearest the home bleachers. Once again he hit his man, but this time the kick was blocked, and the ball bounced toward the near sideline. A Cowboys defensive back scooped it up and looked downfield. Flynt was the only player between him and the end zone. Flynt squared off and the old guys rose to their feet, remembering the way he used to take off players’ heads. But the kid, rather than run at him, headed for the pack at the center of the field. Flynt watched him go, then trotted gingerly behind. He would say later that he could feel his groin muscle with every step, that he knew if he had to perform, it would have ended his season. But he said he’d been ready for whatever he had to do.

Four minutes later Hardin-Simmons scored another touchdown and a lead it never relinquished. The Cowboys won 46—36, and the Lobos’ playoff hopes were done.

Spirits had picked up by the time the former players gathered at the Alpine Country Club for a barbecue dinner. Flynt had made them cool again, and they seemed to have drifted back in time to when they owned the school. Though nonplaying alums were presumably welcome, none came by. The only partygoers who hadn’t played football were the wives, Coach Wright, a couple reporters, and a Hollywood producer named Mark Ciardi, the money behind movies like The Rookie and Invincible.

War stories floated on a stream of free beer, some more believable than others. The men talked about driving opponents into the concrete wall just beyond the sideline and a New Mexican hotel they couldn’t enter before a game because a traveling whorehouse was using the rooms. When Coach Wright arrived, the players’ wives introduced themselves and said they’d never heard his name without the prefix “that SOB.” Everyone marveled at Flynt, how he had remade himself and pulled off his comeback. Throughout the night the running gag for everyone was “Who’s gonna play me in the movie?”

The Thursday morning before the last game, Flynt and I met again in the student center. Until that point we’d not talked about the fight that ended his first tenure as a Lobo. But when we sat down, I gave him a document he’d requested, a short letter stating that Texas Monthly wouldn’t sell his story to Hollywood without his participation and approval. He read it, then started to explain the pivotal event in his legend and life.

It began in the summer of 1971, with Flynt’s telling Coach Harvey that he thought the Lobos had a chance to win conference that year. But he insisted that to make that happen, Harvey would have to enforce curfew. The coach asked him, a returning team captain, to mete out punishments when teammates came in late. That’s what led to the momentous fight.

“We had an athlete here named Jacob Henry, a world-class runner,” Flynt recalled. “His older brother had spent four or five years in jail and then walked on to the team. The coaches didn’t know much about him, but they felt that if he had Jacob’s genes, they’d give him a shot.

“So I was checking rooms at curfew, and Henry’s brother and his roommate weren’t in. Forty-five minutes later they still weren’t. But Fletcher Hall was horseshoe-shaped, and looking over the balcony, I saw them in the courtyard, on the steps smoking cigarettes. I could see the cigarettes.

“I walked down there and said, ‘You guys know what time it is?’ I could smell alcohol on them and felt it was pretty brazen to be smoking. The coaches definitely didn’t want us doing that. I said, ‘Tomorrow morning at six a.m. we got some cars that need washing.’ The Henry guy had a few things to say, and now I could see it coming. I knew this guy’s history. I figured, ‘Well, he doesn’t mind fighting, so that’s what’s going to happen.’ When he thumped his cigarette and came off the step, I hit him. Broke his nose. He went down and out.”

Flynt said the roommate began hollering, waking up the dorm, including Coach Flop Parsons, who lived there with his wife. Guessing Henry had a concussion, Parsons called an ambulance. Then things got crazy.

“Everybody’s awake and screaming now, and the ambulance comes and loads the kid up. Then on the way to the hospital, he gets out of the ambulance. And he tells the driver, ‘I’ve got a gun, and I’m fixing to kill Mike Flynt!’ and heads back for the dorm. So the driver calls the police, who send squad cars and call the coaches and the university president, Dr. McNeil. And then they locked down the dorm, sent us all to our rooms. Well, we’ve got practice the next morning, so I just went to bed.

“The next morning, Coach Parsons came in around seven o’clock and said Coach Harvey wanted to see me down in the dressing room. When Coach Harvey let me in, he said McNeil had called and told him it was either him or me. The graduate assistants were in my room packing my luggage. They loaded me up and took me to Odessa.

“That fast . . .” he trailed off, “it all was over.”

Flynt nutshelled the rest of his life. He married Eileen in 1972, then finished college at UT-Arlington. In 1976 he talked his way into a strength coaching job at Nebraska with Boyd Eppley, a legend in his own right who all but invented modern football strength training. (Notably, Flynt got in a shoving match with Nebraska’s all-American center in the weight room his first day on the job.) In 1978 he went to Oregon and became the first strength coach in the Pac-10. The next year he took the same job at Texas A&M.

He left in 1981 and started working with children. He created a children’s workout video that he sold at homeschool conferences and eventually invented his Powerbase equipment, which he now sells to individuals and school districts. And somewhere in there he got right with God. “It was just depression over things that weren’t going the way I thought they should. I was drinking too much, really at rock bottom.” One night he went on a walk with Eileen. She quoted Scripture to him. “All of a sudden, it just sort of settled in on me.”

It was a remarkable story, of a life begun in prideful mistakes and redeemed in peaceful humility. Flynt spoke eloquently and at length about how humble he felt. It was no wonder that for more than 25 years some of his old friends had been expecting a big-screen depiction of his legendary life.

But legends are tricky. At their essence they’re stories crafted of memories that, with the passage of time, can come to look more like the legend than the events they recall. There’s not always room in the legend for being merely human, for the moments in a real life that point away from the pedestal.

Flynt didn’t talk much about the eighties. But buried in the mountain of media coverage of his historic 2007 season was an October blog post written by a Baptist minister who’d taught Sunday school to the Flynts after they moved to Tennessee, in 1985. He thrilled at the comeback, described praying with Eileen, and called Flynt a friend. He also recalled Flynt’s frequently approaching him with investment opportunities. “I never bought the stock he offered for Gold Mining in Arizona,” he wrote, “or the stock he offered about raising the Titanic. A little off-the-wall for someone like me.” When I asked Flynt about that in a December phone call, he said he’d once done consulting work for a man who was doing contract work for RMS Titanic, the Florida company that began retrieving artifacts from the shipwreck in 1987. But Flynt insisted he would not have offered stock because he had never held a license to sell securities.

The gold mine reference was more complicated. It was related to a series of investments Flynt had entered into in 1981 with a childhood friend from Odessa. The deals were ultimately determined to be a pyramid scheme that bilked hundreds of people out of tens of millions of dollars. Flynt had been close enough to the pyramid’s top to have been indicted, along with his friend, on four counts of felony fraud in 1985. The friend was convicted, but the charges against Flynt were dropped three years later, according to court filings, after he paid restitution to an investor who’d gotten in through him. When I asked Flynt about the scam, he said he’d been a victim too. He called the experience a painful nightmare. Presumably, that was the rock bottom to which he’d referred.

As for the fabled “one fight too many,” the hinge on which the Flynt legend swings, I talked to thirteen of his 1971 teammates about the infamous fight. Some had witnessed it in the courtyard, some had been inside the dorm and come out for the ensuing melee, and others had merely heard the next morning’s reports. Their memories had diverged over 37 years, and they told conflicting stories. Some cited the curfew violation, but others remembered the fight’s taking place in the early evening while the sun was still out, and most said that the real crime was that Jacob Henry’s brother, whose name was George, had shirked his freshman duties. The team had a tradition of initiating newcomers, who had to shave their heads and wear beanies until the Lobos’ first win. They were frequently made to wash upperclassmen’s cars. “Even in the rain,” a friend of Flynt’s joked.

Every player I talked to said that when Flynt made his demand of George, the freshman mouthed off and Flynt coldcocked him. But what Flynt left out of his version was that George was black. Though no former player, black or white, suggested or implied that race had anything to do with the punch, they all said that the commotion that followed, which was described as either a face-off or a gang fight, was divided along racial lines. They said no ambulance had come for George—most said they didn’t think Alpine even had an ambulance in 1971—and that he had never threatened to kill Flynt. Coach Harvey told me that the police had not been called, nor had president McNeil called him. Harvey’s concern had been that the fight would split the team, that bad feelings would resurface throughout the season. He said that was why he had made the hard decision to kick Flynt off the team.

But the bigger problem with Flynt’s story had to do with George Henry, whom I reached on the phone in December. He had recently retired and was moving to Kentucky from Denton with Jacob, who was actually his older brother. It turned out that George had been a true freshman in 1971 and that he had never, as Flynt stated, been in prison. He was nineteen years old and, at barely 150 pounds, the smallest player on the team. He also said he didn’t smoke back then.

“It was getting on to dusk,” George recalled, “and Flynt told me, ‘You’re going to wash my car tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Wash it yourself.’ He got pissed and threw the first punch. I don’t know why he’s saying this stuff now. I’ve always said I hated to see him kicked off the team. He was a good football player. We could have used him that year.”

After talking to George, I called Flynt to reconcile the stories. He quickly grew angry. “Look, I didn’t even have a car,” he said. “Apparently it’s pretty foggy to a lot of people if you’re getting this many stories.”

He tried to make his version fit with the others. He said that he had not actually seen the ambulance himself but had heard about it from Coach Parsons. He said that perhaps Coach Parsons, who’s now dead, had told him about the ambulance and the gun to get him to stay in his room. And he said that Coach Harvey had definitely mentioned McNeil, maybe to pass the buck. As for George, he said, “It was my understanding that he’d been in jail. I didn’t create that. As far as I’m concerned, the fight took place for whatever reason it took place, and it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Whether I hit him with a left hook or an uppercut, all that’s immaterial.

“If you can’t get comfortable with the facts, just don’t write the story.”

With 3:39 left to play in the season finale, against Mississippi College, Flynt finally saw game time at linebacker. The Choctaws were up 56—35, and Davidson, trying to engineer another miracle, had just been intercepted at Mississippi’s 14-yard line. Even in a season in which anything seemed possible, this unmistakably ended any chance of a Lobos victory. But it did nothing to the excitement level in the Jackson Field bleachers. Flynt’s five games spent blocking on kicks had been inspiring but uneventful. Here was his chance to complete his dream.

After watching a 4-yard pass, Coach Wright called a time-out to send Flynt in. The crowd reaction was exactly as expected. The Baby Boomers who were as hungry as Flynt, started chanting, “Push ’em back, push ’em back, way back!” Camera crews and photographers jockeyed with Lobos players for angles, and reporters scurried to find the Flynt family. As before, Flynt had no time for kudos or reflection. He later told the AP, “I was totally focused on my responsibilities.”

The first play was a run to his side. Flynt hooked up with a 270-pound offensive guard who was pulling on the play and watched the Choctaws tailback dart inside, gaining 3 yards. The next play was a handoff that went the other way. Flynt started in pursuit, then tripped and fell on teammate Chris Vela. The two watched the end of the play from their bellies.

On third down, Mississippi ran up the middle. Flynt was blocked out of the play but, refusing to quit, followed the ball carrier and jumped on the pile of tacklers 6 yards down the field. There was less than a minute to play as an official signaled first down. One more snap and the quarterback took a knee. Thirty-nine years after it began, Mike Flynt’s Sul Ross football career was over.

If the postgame scene on the field could have been viewed from above, the crowd would have looked like ants running for a dropped piece of candy. Everyone wanted a picture taken with Flynt, the players, their parents and girlfriends, the opposing coaches, and the referees. Reporters lingered on the periphery, trying to be respectful before moving in.

There was one person in the crowd who did not hustle to Flynt. Near the visitors’ benches, Coach Wright was lying on his side, picking at the grass. I walked over and sat down next to him.

“You know,” he said, “it’s so impressive to have bounced back after the way the first half ended. What were we down there, forty-two to fifteen? And for us to start the fourth quarter down only thirteen? Folks, if we convert that fourth down, we’re one play away—or one holding call or one interference call—from winning that ball game.”

He sat up, put his hands on his knees, and looked at the scoreboard. Then he watched the crowd.

“Isn’t this team fun?” he said. “God, if the injuries hadn’t hit us this year. I tell you, they’ve got something that in thirty years . . .” He grabbed another piece of grass and flashed a washed-out grin, looking significantly more worn than he had at the start of the year. A football season will do that to you.

He was already thinking about next year. He said Flynt had promised to be the liaison to the Boomers, to help realize his comeback’s institutional benefits by organizing fundraisers and game-day reunions. Then he talked about players he hoped would return. “Jamal Groover should eventually be able to replace T. J. Barber. And Carlo Dominguez will be a hell of a lot of fun to watch, wherever we play him.” He showed no indication that in a month’s time he’d resign.

I left him to find Flynt. As he finished talking to an El Paso news crew, I jumped in and asked what he felt he’d accomplished. “Personally, I came back and helped a group of young men I didn’t know, and that’s what I set out to do—to right what I felt was a wrong. I’d like to think these young men are better off for having known me. I know I’m better off for having known them.” Humble to the end, he gave no sign of the big developments coming his way. In mid-December, shortly after Coach Wright’s resignation, Flynt would sign with the sports marketing firm started by NBA superstar LeBron James. The agency would negotiate his movie and book deals, as well as arrange endorsements and speaking engagements. There would eventually be talk of a Mike Flynt—model Nike shoe. As a second news crew fired up its camera and nudged me away, Flynt fell into the crowd for more hugs and handshakes.

Somewhere in there, Flynt would later tell me, he had a short conversation with one of his teammates. He said he thought it was Kyle Braddick, an eighteen-year-old linebacker who saw most of his action on kick returns. Braddick played recklessly and left nearly every game banged and bruised. But he kept coming back, and Flynt was part of his inspiration.

“Kyle said, ‘Mike, I wanted to see you intercept a pass and run it back for a touchdown.’ And I said, ‘I know, Kyle. Maybe we can do that in the movie.’”