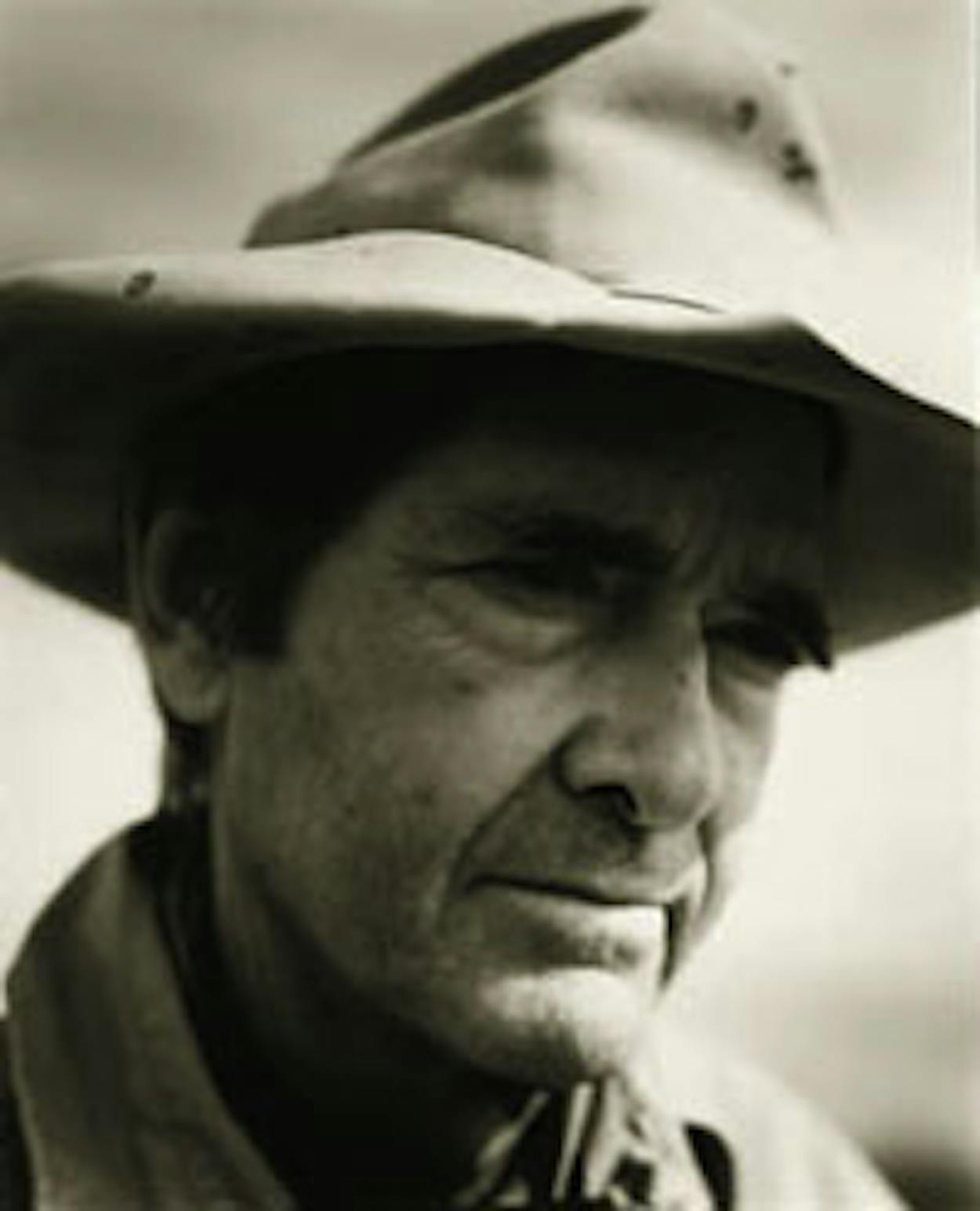

GENE RISER WHEELS HIS PICKUP over the caliche road in the thorny South Texas brush country near the town of George West, halfway between Corpus Christi and San Antonio. He’s showing off his 2,500-acre mesquite-studded property while explaining why he became a deer rancher. His grandfather, he tells me, bought this land and tried to make a living as a cattle rancher. He barely made ends meet. Riser’s father cleared a lot of the brush away and tried to farm the land, but the lack of rain doomed that effort too. In the sixties Gene left the family farm and took up other work. His father still kept a few cattle on the ranch, but that business, in Texas and elsewhere, was an increasingly bad bet. Over time the family land had been overgrazed, abused, hunted-out, and rendered more or less useless. If not for a small oil and gas lease, the family might have had to sell it off.

Then, in 1987, the Risers decided to try another way to earn money from their land. Instead of selling farm produce or cattle, they focused on selling hunters the right to kill deer on their property during the three-month hunting season every fall and early winter. To do this they put up an eight-foot-high fence to keep their white-tailed deer from roaming onto their neighbors’ property and to keep other deer from coming onto the Riser ranch. The Risers then selectively hunted the deer and allowed the herd to mature fully, something that rarely happens to deer on low-fenced lands. Older deer are larger and have bigger antlers, which allowed the Risers to charge higher prices for hunting leases.

The idea was not exactly new. High fences were already a signature of many South Texas and Hill Country ranches. They had first been erected in the thirties on spreads such as the YO Ranch near Kerrville to contain exotic game imported from Africa for the purpose of hunting—a lucrative means of supplementing ranching income. But the Risers and others like them wanted to use the same type of fence for what was already there—white-tailed deer—the one species of ungulate that is native to almost the entire state. The idea worked. The operation ultimately allowed Gene Riser to move his family back to the ranch.

Two years after the high fence went up, Gene Riser went one step further and became one of Texas’ first scientific deer breeders, a business that became legal for the first time in 1985. Under the new law, up to 320 acres could be set aside to improve the breed with stud stock from another game breeder. That stock and their progeny are the property of the game breeder and, unlike wild whitetails, can be bought and sold. Riser built some pens on a forty-acre plot, bought some hardy whitetails from other ranches, and started his breeding business. His main market: high-fence deer ranchers who wanted bigger bucks with bigger antlers.

This idea worked even better—and, indeed, was already working around the state for other ranchers trying to survive in a brutally depressed cattle market. The 56-year-old Riser now makes money from both operations, hunting and breeding. He doesn’t intermingle the deer he breeds with those on his hunting acreage because the breeding stock is far more valuable.

Deer ranching is hardly an isolated practice on a few experimental properties. What Riser is doing with his land is being replicated all across the state of Texas and especially in South Texas and the Hill Country. Our state leads the world outside of South Africa in high fencing: at least 3 million of the 16 million acres of deer habitat in South Texas are now high-fenced. High fences and genetics, combined with the huge natural constituency of hunters who will pay handsomely to hunt deer are effecting a massive change in land use. For large swaths of the state, what is happening amounts to the de facto privatization of deer, a wildlife resource that is defined by law as the property of the people, and the redefinition of hunting as a sporting amusement reserved for people who can afford hefty fees, similar to the system in Great Britain today. It has also caused an increasingly bitter controversy among landowners, hunters, and government regulators.

The first charge leveled at deer ranchers like Riser comes from their potential clientele, the hunters themselves. How, critics wonder, is it really “fair chase” when you shoot a corn-drunk whitetail that is confined on fenced land? And indeed, the Boone and Crockett Club, the arbiter of game records in North America, does not certify trophy deer taken within high fences. Someone who high-fences a spread, then jams it with imported whitetails who are then baited and shot, is engaging in what many people believe to be unethical hunting.

The second charge is more serious, and more practical. Confining deer within high fences can lead to overcrowding and the infection of whole herds with diseases. These include anthrax and chronic wasting disease. The latter, which is the wildlife equivalent of mad cow disease, has broken out on high-fenced elk ranches in Colorado over the past year, prompting the Texas Animal Health Commission, the agency which regulates domestic livestock health in our state, to ban the importation of both deer and elk from Colorado. Those same factors influenced the citizens of Montana in a statewide referendum last year to ban new game farms and prohibit property owners with high fences from charging hunters to shoot game within their enclosures.

“Anytime you put white-tailed deer or any animal in a confined area where their numbers are concentrated, you run a very high risk that disease will break out,” says Scot Williamson, the director of big-game programs for Parks and Wildlife from 1990 to 1993. “Landowners who say that they’re not going to let the deer on their land get a disease just don’t know enough to make the claims they’re making. There are too many variables, especially when you’re moving deer in from out of state. The risk is too high.”

Behind all this is an even larger question: whether deer that have been genetically manipulated or imported should be considered livestock or wildlife. As wildlife, they are a freely moving, natural resource that by law belongs to the people of Texas. As livestock, they stay where you put them (or export them) and are the property of the landowner who feeds them, breeds them, improves them, and makes money from them. From a regulatory standpoint, the two categories are radically different and almost completely irreconcilable.

And regardless of the definition, another ethical question remains: whether wildlife can or should be penned in at all. Doing so often requires drugging an animal so that it can be restrained. The stress as a result of capture, transportation, and relocation can kill a deer. Is “improved genetics” of our publicly owned deer herd worth that price?

I AM NOT A HUNTER. You might even be inclined to call me a tree-hugging environmentalist, so what I am about to say may surprise you. Not only am I in favor of the practice of using high fences to breed deer for contract hunting, but also I think it may be one of the few good things to happen to the land in this state since the days of the open range. I feel that way because of two basic truths that have gotten lost in the middle of all this fussing and feuding. The first is that private hunting preserves offer a practical solution to a larger question that has plagued Texas like few other places: In a state where wide-open spaces are practically a birthright but where 97 percent of the land is privately owned, how do you keep folks from selling their land to developers and forever destroying natural habitat? While there may be considerable public sentiment to purchase more lands for the enjoyment of the people of the state, it is unlikely that it will happen anytime soon because of tight budgets and the difficulty in managing the property the state already has.

Besides allowing ranchers like Gene Riser to keep the family land intact, deer ranching provides an incentive to restore the land to its original state, with native trees, brush, plants, and grasses. And while it might seem that such fences would severely restrict the movement of other animals, in fact the barriers are surprisingly porous. Some 550 species, many of which are also hunted, pass over, under, or through them (mountain lions climb the fences, javelinas dig under them). For most of those animals, life is no worse because of the fences, and may even be a bit better on ranches where land is no longer cleared.

Still, wouldn’t it be better if the ranch lands were turned to some other agricultural use? The answer depends on what your priorities are. Peach orchards, pecan groves, wine grapes, and other specialty crops are seemingly benign means of making money off the land. But they require extensive clearing of native brush and lots of water, fertilizers, and pesticides. While such cultivation has its place in the ecosystem, if all of Texas were farmed like that, the wildlife that lives off the land would not exist. Besides, there are just so many such businesses that the land, the water supply, and the greater economy can support.

The same goes for running goats and sheep. There is money to be made from them, although that economy may not be sustainable without government price supports. Worse, those livestock have a history of chewing all grasses and other small plants down to the root in times of drought, often ruining the land altogether, a legacy that is clearly visible on rocky spreads throughout the Edwards Plateau.

The second truth is that, whether we like it or not, hunting just isn’t what it was in Davy Crockett’s day. As noble as the concept of stalking animals across vast expanses of land for days on end may sound, that kind of hunting no longer really exists in Texas. People may remember the good old days when they took up their varmint guns and headed off into the nearest thicket. But they were likely hopping someone else’s fence to do it. Since then, ranches have grown smaller and landowners have grown far more particular about who hunts on their land. The truth is that most people pay to hunt. The only question is, How good is the game on the lease?

The reality—again, whether we like it or not—is that modern hunting often means packaged three-day hunts, selecting game from a photo album or a video, agreeing on a price for a particular animal, then riding around in specialized vehicles or sitting in climate-controlled deer blinds near automated corn feeders and waiting to pull the trigger. Fenced hunting preserves are an integral part of this trend; they are where American hunting is going. I admit that the issue of disease caused by overcrowding confined herds makes me nervous. But after talking to experts on both sides, I am inclined to believe the advocates of high fences who say that as long as Parks and Wildlife is able to regulate the private deer-ranching business—especially those ranchers who put large numbers of deer on small spreads—disease can be kept to a minimum.

AT GENE RISER’S PLACE IN South Texas you can see how hunting on a high-fenced game ranch works, both as a business and as a sport. A few days after my visit, a party of three from Mississippi was due to arrive at his ranch for a three-day package hunt in which Riser would house them, feed them, and escort them to a blind where deer were known to feed. A later group of five from California chose to rattle antlers to attract their quarry. The hunters pay a flat fee for the experience and a bonus if one of the party bags one of the bigger bucks roaming the ranch. “A big, mature eight-point will cost $2,500,” Riser says. (The size of a male deer’s antlers is determined by the number of tips, or points, on its rack.) “Ten points will fetch $3,500. And if he’s a wide and beautiful ten-point deer, with twenty-inch antlers, it’s $5,000. This season I’m getting eight paid hunters averaging $3,000 apiece. I could get a lot more than that, but I’m holding off to raise more mature bucks.” He can demand that price because, he says, “We supply them with a better product. If I don’t have high quality, I can’t charge a high price.” He now makes $50,000 every year from his hunting and breeding businesses, though he says he could make more than that from breeding alone.

Riser pulls up to the heart of his breeding operation, a cluster of fenced-off areas containing some eighty fawns and a barn. He stops to pet one spindly legged animal on the head while cooing to her. He calls her Baby. In a nearby pen are breeding does and a buck. A nine-acre plot holds 25 yearling bucks. “Over there is a two-year old,” he says, pointing to a robust-looking buck. “He’s going to be one of the biggest on the ranch. He’s typical of what is going on here. Deer are exploding in size, which is the result of genetics. But in this brush country, you also need age and food.”

Riser’s investment has been substantial. To build an eight-foot fence—the minimum to prevent whitetails from jumping over it—costs anywhere from $10,000 to $18,000 per mile. Barns and pens must be built. A biologist has to be retained to develop a management plan. This is the tricky part, because the number of deer per acre that a piece of land can support depends on the terrain, vegetation cover, and water sources. Breeding stock can cost up to $5,000 per deer, and buck semen for artificial insemination runs anywhere from $200 to $2,000 a straw. Nutritional feed must be purchased to supplement the normal diet.

After that the deer must be allowed to age. The average age of deer taken on low-fenced land in Texas is two years. If deer survive at least five years, or ideally, seven years for full maturity, they’re more apt to grow the kind of antlers that translate into big money.

Riser defends the practice of guiding hunters to blinds and baiting the deer with corn—which some have likened to fishing in a barrel—as a necessary part of the business. “Without that, you won’t see a deer,” he says. Fewer than 240 head of deer roam his land, or fewer than one per ten acres. “When you’re hunting behind a high fence, it doesn’t make hunting easier. My deer will be nocturnal by the time they’re three or four. They disappear. These guys are smart. You seen any today?”

I have not. But I also know that there are plenty of other deer ranchers, less ethical than Riser, who are fencing off smaller acreages, filling them with so many deer that the animals must be fed year-round to survive, and then arranging easy hunts. I do not approve of what they do. On balance, however—and though it goes against almost everything I used to think about hunting—I can see nothing harmful or unethical about what Gene Riser has done to his ranch. And it is probably the best thing that could have happened to this land.

IF YOU HANG AROUND HUNTERS long enough, you are certain to hear the term “deer queers.” They represent a growing subgroup of deer hunters who eat, drink, and sleep trophy bucks. They’re easy to pick out on the highway. Their pickups, SUVs, and sedans are the ones with the distinctive skull-and-antlers sticker in the rear window. The logo was designed by the most visible and influential of all deer queers, Jerry Johnston, a strapping middle-aged man with an abundant mane of white hair and a matching walrus mustache. Johnston is the founder and president of the Texas Trophy Hunters Association (TTHA) and the co-founder of the Texas Deer Association, which occupy separate offices in an anonymous San Antonio office park just inside Loop 410.

Johnston started Texas Trophy Hunters almost thirty years ago. But it has been only in the past five years that interest in trophy hunting—as opposed to plain old deer hunting—has blossomed, according to Johnston. This coincides with a seismic, generational shift in the sport: More and more hunters are now city dwellers with limited time who want instant gratification. The result is that hunting is now more often than not a highly organized activity run by professionals for enthusiasts who want the biggest possible deer in the least possible amount of time.

Johnston wants to do for trophy hunting what sportsman Ray Scott did for bass fishing—popularize and professionalize it—and so far, he’s done an effective job. Sixty thousand readers purchase copies of The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, a bimonthly magazine chock-full of hunters’ stories (“Remembering Dale Earnhardt: Fast Cars and Big Bucks,” “Kimble County Monster”) sandwiched between advertisements for rifles, hydraulic hunting blinds, hunting leases, and automated feeders. More than 100,000 people attend the TTHA-sponsored Hunters Extravaganzas held every August in Fort Worth, San Antonio, and Houston. You can watch Johnston every week on the half-hour Texas Trophy Hunters Show, on the Outdoor Channel. Though Johnston insists that his main objective is to improve the “quality” of the deer, the message being conveyed through those media is, It’s not about the meat anymore, or the chase, or the man versus beast struggle. It’s all about large, multipoint sets of antlers that you can mount over your fireplace. “Back in the old days, in a deer camp, when the hunting season opened, the hero of the camp was the one who got the first buck,” explains Johnston. “It didn’t matter if it was ten points or not. We didn’t think of management for quality. That kind of thinking has changed.”

His organization is the most visible advocate for high fences and for the right of the landowners behind them to manage their property as they wish. His influence is evident in the photographs hanging on the walls of his office. They show Johnston posing with Nolan Ryan, Ted Nugent, Goose Gossage, Slim Pickens, Earl Campbell, Red Duke, and Chuck Yeager. His argument boils down to this: The person who owns a ranch is the true steward of his land and should manage his own wildlife. This is in total opposition to tradition and history in Texas; the state has always regulated wild animals. “What happens in here is not going to affect anyone but me,” says Johnston, who has a three-hundred-acre high-fenced ranch near Castroville. Self-interest is a persuasive tool in keeping the deer on his land free of disease, he says. “If something goes wrong inside a high fence,” he asks rhetorically, “who’s damaged?”

In addition to the Trophy Hunters Association, Johnston helped start the Texas Deer Association three years ago as an advocacy group for scientific deer breeders. The idea was to try to fight some of the rules imposed by Texas Parks and Wildlife, which many breeders claim are unusually onerous and restrictive. The paperwork required to breed deer and to conduct hunts is the stuff dreamed up by bureaucrats. Parks and Wildlife is all about the number of deer on a given piece of land, breeders point out, not what kind of deer are on that land, which explains the runty condition of deer overpopulating lands on the fringes of Texas cities. The regulators are slow to adapt to change and are not inclined to accommodate high-fenced game ranches. “We understand why law enforcement wants certain things done,” says Johnston, “but how they get those objectives isn’t helping deer, as far as we’re concerned. The rules and regulations are being designed by non-users. Texas is way ahead of other states in terms of managing wildlife, but the state’s deal is quantity. Quality isn’t a factor in those regulations. Landowners just need to be turned loose. It’s been like pulling teeth.” Then he adds, “The state needs to see a separate set of regulations for intensively managed high-fence property.”

“GAME MANAGEMENT,” SAYS JAMES Kroll, driving to his high-fenced, two-hundred-acre spread near Nacogdoches, “is the last bastion of communism.” Kroll, also known as Dr. Deer, is the director of the Forestry Resources Institute of Texas at Stephen F. Austin State University, and the “management” he is referring to is the sort practiced by the State of Texas. The 55-year-old Kroll is the leading light in the field of private deer management as a means to add value to the land. His belief is so absolute that some detractors refer to him as Dr. Dough, implying that his eye is on the bottom line more than on the natural world.

Kroll, who has been the foremost proponent of deer ranching in Texas for more than thirty years, doesn’t mind the controversy and certainly doesn’t fade in the heat. People who call for more public lands are “cocktail conservationists,” he says, who are really pining for socialism. He calls national parks “wildlife ghettos” and flatly accuses the government of gross mismanagement. He argues that his relatively tiny acreage, marked by eight-foot fences and posted signs warning off would-be poachers, is a better model for keeping what’s natural natural while making money off the land.

A trip to South Africa six years ago convinced Kroll that he was on the right track. There he encountered areas of primitive, lush wildlife-rich habitats called game ranches. They were privately owned, privately managed, and enclosed by high fences. He noticed how most of the land outside those fences had been grazed to the nub, used up. “Game ranches there derive their income from these animals—viewing them, hunting them, selling their meat,” he says. “There are no losers.” At his own ranch Kroll has set up a smaller version of the same thing. His land is indeed lush, verdant, with pine groves, an abundance of undergrowth, wild orchids, New Jersey tea, jack-in-the-pulpits, and other native plants. He has also set up a full-scale breeding research center and is one of twenty Texas deer breeders using artificial insemination to improve his herd. “We balance sex and age ratio,” he says. “We manage habitat. We control the population and manage for hunting. I want to leave the deer herd better than it was before we came.”

When the subject of chronic wasting disease on high-fenced elk ranches in Colorado is raised, he casts a wary eye. “You know where that started? On a state-run research farm.” He believes that private landowners would never let that happen. Like Johnston, he argues that the landowner who relies on his land for a living has plenty of motivation to keep diseases at bay.

Lately the power has been shifting in Kroll’s direction. Last year deer-ranching interests persuaded Parks and Wildlife to alter rules and allow landowners to choose their own biologists in creating wildlife-management plans for their land, rather than have one from Parks and Wildlife. That has given landowners more freedom, says Kroll, but he wants even more. “You still have to let the state on your land to get a wildlife-management permit,” he says.

THOUGH HIGH FENCES REMAIN the subject of hot controversy, more and more experts seem to be coming to the opinion—however reluctantly—that when used properly they can be good for both hunters and environmentalists. Scot Williamson, the former director of big-game programs for Parks and Wildlife, isn’t particularly fond of the concept of high fences, but he condones the practice as long as it’s on land that would support the wildlife on it naturally. “If you have a twenty-thousand-acre ranch that is high-fenced, your conditions for managing your deer herd for quality and proper density are much better,” he says. “At the end of the day, the ecological health of that ranch is improved. But I don’t extend that to a two-hundred-acre place where you have to systematically feed your deer. You’re not improving your natural habitat or helping the ecology. All you’re doing is making money. If you’re going to enclose a deer herd, that herd should be able to survive without supplemental feed.

“Even the ultrapurist Boone and Crockett Club has begun to recognize that there may be no turning back. Though the organization still refuses to certify game that has been confined by artificial barriers, it recently formed a committee to set up a separate category in their North American Big Game Records Program for game taken behind high fences. Several other states already have some high fencing, including Michigan and Colorado.

I’m not sure it’s right for them. But for Texas, it’ll do, given the circumstances. Look at it as one of the latest manifestations of our peculiar, long-standing cultural relationship with hoofed creatures—from horses, buffaloes, cows, sheep, and goats to exotics like llamas, zebras, and scimitar-horned oryx. In a strange way, ranching the white-tailed deer brings the relationship full circle, back into the (tamed) wild, back to nature.

For those hunters and non-hunters who are still troubled by the ethics of high fences, I offer a quote from Dr. Deer on the subject. “Think of it from an anthropomorphic standpoint,” he says. “Cattle, we raise in pens, load them up, and knock them over the head. Deer, we raise and then release them into their native habitat. They’re harvested with guns and bows. If you had to be cut down, how would you want to die?”