Sandwiched between a crucial presidential election year and a crucial gubernatorial election year, 2009 has been the period in which just about all politics in Texas really has been local: Nearly every major city has had a decisive mayoral election or, in the case of Dallas, hard-fought referendums that tested its mayor’s power. In San Antonio and Austin, where mayors had reached term limits, change was inevitable—and, mostly, welcome. The young, glamorous Julián Castro trounced the establishment’s choice to succeed Phil Hardberger in San Antonio, while in Austin, back-to-business Lee Leffingwell replaced the laid-back Will Wynn. In Dallas real estate mogul Harlan Crow forced Mayor Tom Leppert into two recall-like fights over city infrastructure; that Leppert won was not only a personal victory but also one that signals the waning of time-honored Dallas kingmakers.

And now comes Houston, which is facing the mandated departure of three-term mayor Bill White in November. Beyond—or behind—civic issues, mayor’s races are always about identity, and because Texas cities are comparatively young, the same evolutionary arguments are replayed time and again. In San Antonio the fight is about ethnic versus Anglo power; in Austin it’s environmentalists versus developers; in Dallas it’s about image—who will best make Dallas the world-class city it perennially longs to be. The Houston mayor’s race has historically been a struggle between those who champion growth at all costs and those who long for some semblance of order, but this year it’s about something more. Specifically, the city that prides itself on moving ever forward is in a political funk over the idea of losing the immensely popular White. As T. J. Huntley, one of the fringe mayoral candidates, blurted at a recent forum, “We should continue his programs. He’s one of the greatest mayors I’ve ever run across.”

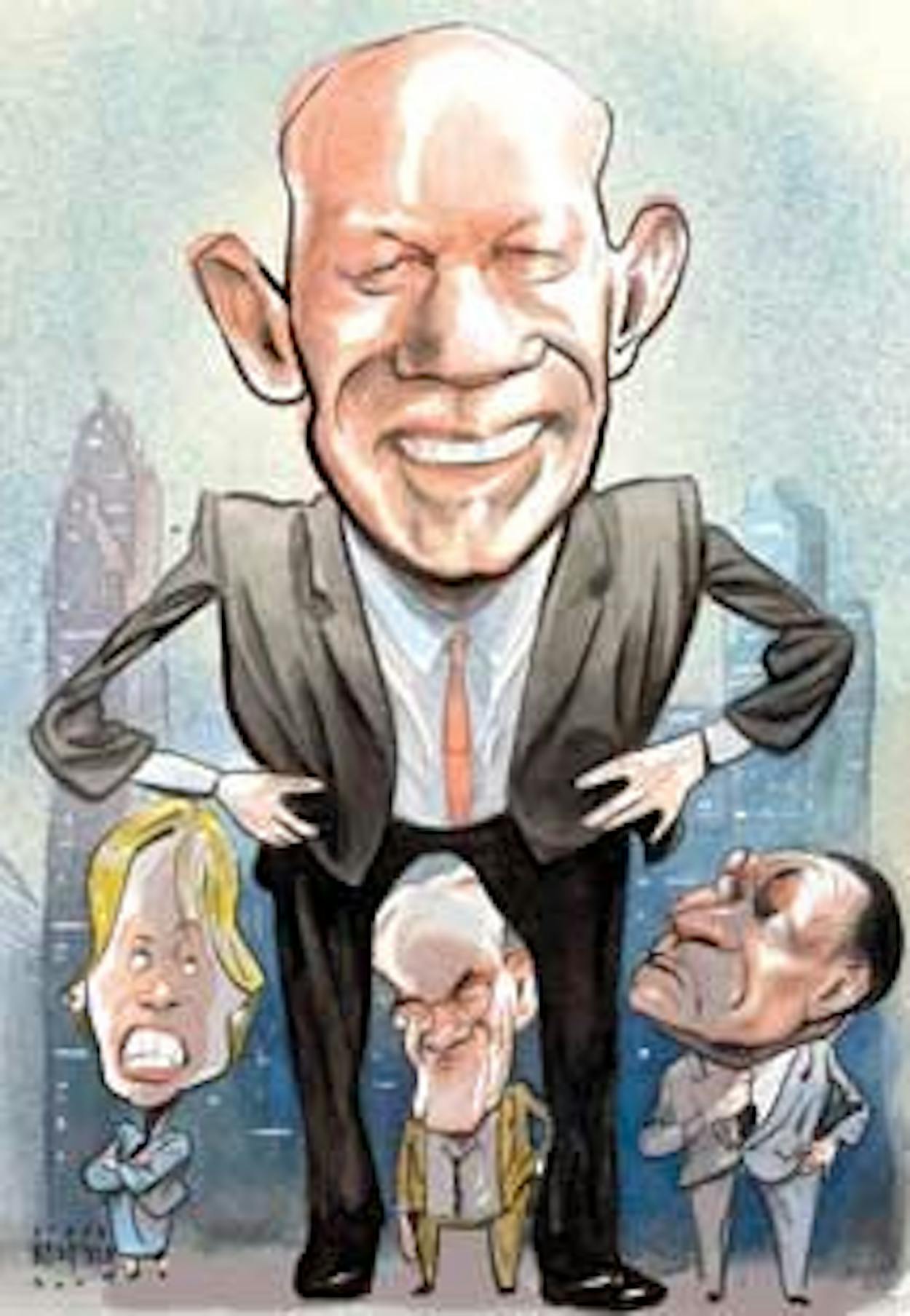

Three serious candidates are vying to replace him, and from the outside, the race looks big-city-progressive: Annise Parker, a gay woman, has been city controller for five years and, before that, sat on the city council for six; Gene Locke, an African American, is a former civil rights activist turned establishment lawyer; and Peter Brown, a wealthy, white eccentric, is an architect who has served on the city council since 2006. But so far the response to these candidates has ranged from denial to disinterest to outright dread. At a forum in June sponsored by the Houston West Chamber of Commerce, the three offered a torpid game of small ball, even though—or perhaps because—the voters in this conservative part of town will likely decide the race. Brown, white-haired and bespectacled, kept his storied energy in check while urging the need for new servers for the city system. Locke was warm and low-key as he subtly reminded the audience that he was the secure pick: He’d been anointed by much-beloved former mayor Bob Lanier (1992—1998), for whom he had served as city attorney. “I know government. I represent government,” he told the crowd of about one hundred. Parker, who has a reputation for being low-key herself—unlike other Houston controllers, she has never positioned herself as a mayoral watchdog to advance her political ambitions—wore a staid suit, and her hair was styled like a GOP matron’s. She touted her fiscal experience, which included the creation of a rainy day fund that has shrunk considerably since Hurricane Ike and the recession. “I want Houston to be cleaner, greener, and safer,” she said. “I’ve been working on this for thirty years.” Clearly aware that running the city required not just management but also leadership, she alone seemed to connect with her listeners.

But none of the three could promise the one thing Houstonians want most: more Bill White. “If you put them all together, you’d have the perfect candidate,” says Nancy Sims, a former political operative who keeps tabs on the race on her blog, mayoralmusings.com. Being mayor of Houston is more like being mayor of New York than, say, mayor of Austin. The fourth-largest city in the U.S. sprawls for miles, is as ethnically and racially diverse as the UN, and, unlike other major Texas cities, has a strong-mayor system: The mayor actually has to run the place without the help of a city manager. White—a Harvard graduate, a successful trial lawyer, and a former deputy secretary of energy, as well as the former CEO of a global investment company—brought a new sophistication to city government. Lanier got streets paved and neighborhoods policed (believe it or not, this was novel then); White pushed quality-of-life issues in a way that Houston’s long-opposed business leaders finally understood. He convinced them that without better parks, schools, and air, no one would want to move to Houston, and the constant growth that had always fueled its economy would disappear. White united the city in new ways (rich Republicans from Memorial joined forces with Montrose lefties), and his six years in office have been blessedly scandal-free. He kept a cool head during Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Ike. He was a shrewd steward of city finances. Not coincidentally, he tackled issues that were transferable to the larger stage, an agenda made evident by his current run for U.S. Senate. “We’ve never had a mayor who wanted to run for higher office,” says Bob Stein, a political science professor at Rice University. “Different ambitions set up different agendas. . . . Lanier’s idea was to pick three things and do one. White picked ten things and did fifteen—well.”

As of early summer, the race had yet to engage the average Houstonian, but politicos were already handicapping the candidates. Brown is by far the richest—he’s married to a Schlumberger heiress—but he’s also considered the flakiest. (His campaign tried to suggest that it was big news that funk star George Clinton endorsed him.) He has done well for his constituents from his at-large council position, whether they are poor blacks or wealthy patrons in the Museum District, but many operatives are dubious that he can broaden his base, especially with a well-regarded black candidate in the race. Parker has the most civic experience—but then there’s her personal life. She has neither advertised nor hidden her sexual orientation—she lives with a longtime partner and their two adopted children in Montrose—and though no one would attack her directly, whisper campaigns among conservative ministers have already begun. Both Brown and Parker have rabid supporters (think of Ann Richards’s), but they are the kind who won’t appreciate a liberal candidate who starts tacking too close to the middle, which is what the winner will have to do.

So far, Locke seems to have the best chance of claiming Houston’s moderate middle. As a divorced father, he put himself through college and then earned a degree from South Texas College of Law while working in an oil refinery. (“Gene’s not Harvard Harvard,” one of his backers said, making an Obama contrast.) He has authentic activist credentials—charges for misdemeanor rioting at a civil rights demonstration in 1969 were eventually dismissed—and he is part of the first wave of local black leaders that included the late Mickey Leland. State senators John Whitmire, Mario Gallegos, and Rodney Ellis endorsed Locke early, and as a Lanier protégé and a partner of the prestigious law firm Andrews Kurth, he is well liked by the developer types who have traditionally controlled the city. But that’s both a blessing and a curse, as some White supporters—powerful career women in particular—fear that Locke will reinstate the good-old-boy, growth-is-job-one system of old. If the election were held today, Parker and Locke would probably make the runoff and, while Parker would probably make a better mayor, Locke would win with the support of the business and black communities. (Blacks make up 30 percent of the electorate in Houston.)

Of course, the election is still months away, which leaves room for what Stein calls “a bad story”: a scandal, a disappearance (to Argentina?), or other drama-injecting news. In fact, the state of city finances could become just that. (“The dirty little secret is that Houston’s broke,” a local journalist claimed recently.) For more than a year, a prominent conservative businessman, Bill King, has been showing local breakfast groups a Cassandra-like PowerPoint presentation that purports to reveal how the city employee pension fund and other “unfunded liabilities” will bring financial disaster to Houston soon—maybe even before the election. If King is right, Brown and Parker, as public servants, will be in big trouble. “Annise hasn’t been waving her hands and saying the sky is falling,” said one campaign junkie. “After eleven years, she can’t run as an agent of change.” A fiscal crisis in the middle of a Senate run would also be bad for White—if he saw one looming. “In brief, Mr. King is just wrong,” White says. “Because we planned ahead and built up cash reserves, Houston is in far better shape than other cities. Our pension systems are also more secure, and the unfunded liabilities have been reduced. It’s not that Houston will be immune to the downturn, but a lot of cities would gladly trade places with us right now.”

Crisis or no, this debate reveals the biggest problem with running in the wake of a wildly successful incumbent: No candidate can attack the mayor directly without losing his support—probably the difference between winning and losing. But a candidate who doesn’t speak out about real problems risks looking asleep at the wheel.

Not surprisingly, the situation has inspired some wishful thinking, mainly that someone with a different skill set would enter the race. “No current candidate can claim they’ll run the city like a business,” says Sims. “There’s no CEO candidate.” The business community’s white knight of choice is currently John Hofmeister, the former head of Shell, who is telegenic, dynamic, and a proponent of renewable energy. State representative Sylvester Turner briefly floated his candidacy, which would have provided some nifty political self-immolation—Turner has longstanding enmity with Lanier, and his candidacy threatened to split the black vote—but not much more. It’s also rumored that if Locke falters, King, voice of doom, might jump in. King probably wouldn’t pull off a victory, but he could challenge the competition to respond to his concerns. As Richard Murray, the former director of the University of Houston’s Center for Public Policy, points out, Hillary Clinton became a much better campaigner after Obama started chipping away at her sense of entitlement.

But until the runoff, at least, the real opponent will be White, as the major candidates try to explain why they can do a better job than he did—or that they can at least keep the city afloat in hard times. As Stein notes, “The banner story will be competence.” In a city known for energy, innovation, and irascibility, that used to be the baseline, not the goal.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy