The yellow door of the Porto-San toilet banged open and out lurched a man who fumbled with the fly of his jeans, then scratched his crotch and stared dully at a pasture decorated with scrub mesquites, the tents and quilts of four or five thousand concert-goers, a far-flung spew of garbage. The voices of Asleep at the Wheel, raised in some hymn to the ghost of Bob Wills, seemed to penetrate the man’s senses, and he lurched toward the stage where the band was performing. The man wore a soiled fedora and a short untrimmed beard. David Allan Coe, his T-shirt read. Damn Near as Big as Texas.

As the man stalked along the trail from the row of privies to the stage, concessionaires tried to entice him with hot links and packaged cookies. “I got Quaaludes!” an unlicensed peddler yelled. “Black Mollies!” Their offers went unacknowledged by the man with the Coe T-shirt. He walked with his spine braced, but his aim was unsteady and his knees buckled, which caused him to wobble and stumble. His fists were clenched. His expression was so sullen, so distorted with macho posturing, that it was hard to take seriously; an approaching girl in a long skirt mocked him, as if to tease him into a happier mood, then laughed quickly when he turned the unamused look on her. The man braked to a sudden halt, stood pondering for a couple of seconds, then swung about and started after her. Apparently unaware of her pursuer, the girl in the long skirt found an unoccupied Porto-San and closed the door behind her. Her follower stood a few feet away, arms folded across his T-shirt, waiting. His expression had still not changed. Before the door opened again, a taller bearded man wearing a knapsack came up to the waiting man and cuffed him hard on the shoulder. Staggered by the blow, the man with the soiled fedora looked ready to fight, then abruptly nodded at his grinning assailant. Side by side they stumbled down the dusty trail toward the stage. I don’t know what the man with the Coe T-shirt intended to say to the girl in the outhouse. I do know the prospect of witnessing that conversation frightened me.

Another girl stood talking to a burly security guard at the barricaded entrance to the backstage area. “This concert is so fine,” she told him. “It’s ten times better than Willie’s picnic was.” Hopefully so. According to one count, Willie Nelson’s last Fourth of July Picnic at Gonzales inspired eighteen overdoses, fifteen stabbings, and seven rapes. The backstage activity at the Outlaw Concert west of Austin was reminiscent of Nelson’s most recent festivals, though not as frenzied. Some of the insiders were old country regulars; one woman who drove up in a white finned Cadillac got out wearing a bright pink pantsuit and a Dolly Parton rack of platinum curls. Others were Austin VIPs. James Street, the former Texas quarterback, stood beneath the ten-foot stage digging his boot heel in the dirt and spitting tobacco. But the most visible backstagers were the Bandidos, whose motorcycles were parked in formation beside David Allan Coe’s trailer. The Bandidos wore uniforms of grimy denim and black leather, and they made no attempt to conceal the handguns bulging from their pockets and stuffed inside their jeans. They wanted people to see those pistols. Earlier in the day, somebody said, one of the Bandidos bloodied the face of a girl who sassed him. The concert promoters had reportedly hired the outlaw bikers to help maintain order at the concert. Nice fellows to have around as a security force. Remember Altamont?

A leaden sky spat rain as Waylon Jennings and his band took their turn onstage. Jennings is one of the outlaw kings of country music, duly anointed by the Nashville powers that be. The cut of Jennings’ beard gives him a rather villainous look, and his predilection for black leather attire enhances the outlaw mystique, but his routine predates the latest fancy of the music industry flacks. Jennings is an old rock-a-billy, the bass player for Buddy Holly’s Crickets, and nothing about his music is new. One of the sad facts of American culture is that if a performer hopes to support himself with his music, more than likely he will lead a subterranean, barroom existence. Few American bars are clean well-lighted places. Redneck drunks have bounced Elvis Presley’s head off the concrete a time or two. Holly used to carry a gun because he was afraid the blacks were out to get him. Jennings’ music grew out of that environment. Nowadays he writes songs of deference to Bob Wills and Hank Williams, and his commitment to country music is no doubt very real, but onstage he remains the aging, hard-luck rock-a-billy: raw, suggestive, handling the neck of his guitar like the phallic prop it is.

Each of Jennings’ songs prompted a roar of appreciation from the crowd, but the loudest ovation came when Nelson appeared alongside to harmonize (if harmony is the word for the impossible mix of those rough-hewn voices) the lines of “Good Hearted Woman.” The sun was down by then, and Nelson was the next act onstage. As is to atone for his much-publicized non-performance at the Gonzales picnic, Nelson worked hard for the crowd at the Outlaw Concert. The same tight nonstop medley kept on and on for more than an hour: a working pace that would exhaust most hard-hat laborers. Willie Nelson is a splendid performer. Flashing that grin, shooting looks of direction to his sidemen, singing songs about the Bible while a plague of insects swarmed in the orange light, Nelson seemed almost angelic as he stepped to the rim of the ten-foot stage. Not too long ago you didn’t have to crane your neck that much to admire Nelson’s stage manner. If you were standing at the foot of the stage in the roadhouses he played in Round Rock and Helotes, you were close enough to touch him. One night in Helotes, Nelson was dogged every step by the lavender Stetson of a front-row true believer. She had a little paunch above her belt buckle and her face was lined and slack with misfortune. As he began his routine of old sad songs she moaned and moved her hips and gulped long swallows from her bottle of beer; when he got to “Pretty Paper” she wrung her hands together and bawled, “Oh yeah, Willie. Oh yeah, yeah, yeah.” Tears were flooding down her cheeks. I’m sure Nelson was moved by her involvement in his music, and he couldn’t stray too far from the microphone, but he looked like he wanted to whistle to himself and edge a few steps away. On the VIP bleachers at the foot of the Outlaw Concert, a happier cowgirl climbed up on her boyfriend’s shoulders, took her shirt off, and offered her pale young breasts to the maestro with an inviting wave of her chartreuse Stetson, but Nelson didn’t seem eager to surrender an inch of his ten-foot advantage. In fact he looked like he’d just as soon jump in a hole full of snakes.

The crowd may have gone a little berserk, but Nelson is no stranger to that scene. The crowds were crazy years ago when he ducked flying beer bottles in the bars of northside Fort Worth. Only now the crowds are much, much larger. Nelson commands upwards of $10,000 for a single performance these days, and people are positively scrambling to get close to his side. Every man he meets has an admiring rap or a proposition. Willie Nelson is the flip side of the Will Rogers homily; I’ve never met anyone who engaged Nelson in social conversation and did not come away liking the man. But as the demands of fame grow more persistent, Nelson is surrounded increasingly by a gang of bareknucklers whose jobs depend upon their ability to protect his cocoon—to say no with whatever force might be necessary.

Nelson has never run with a saintly crowd. His longtime chauffeur and bodyguard, Billy Cooper, handles a gun with practiced ease. When one of Austin’s outlaw camp followers insulted Paul English’s teenaged daughter, English waited until he saw the outlaw joker in a bar, then laid his drumsticks aside, slipped off the back of the bandstand, sidled up from behind, and waited for the young man to turn around. The first punch landed in a fistfight is extremely important; Nelson’s skinny drummer knocked the would-be outlaw cold. Billy Cooper and Paul English live their lives way out on the edge. But there’s nothing sinister about Cooper or English. They can be the best old boys you ever swapped tales with. If you get along with them they’ll get along with you. Some of Nelson’s newer followers are more ominous. Moving around in the shadows of the Outlaw Concert was the hulking blond man, supposedly a former Hell’s Angel, who has hounded Nelson’s operation for the last several months as a self-appointed bodyguard. Unlike the Bandidos, the blond bodyguard wears his gun holstered on his hip, a left-handed gunslinger. Reportedly he’s an expert in the art of pistol whipping. He hopes some fool will get out of line. The blond man’s not overly concerned with Willie Nelson’s art. He’s far more taken with the outlaw mystique. Nelson knows what’s going on around him. At the Gonzales picnic he told his chief disburser to keep the blond man off the official payroll because there was no telling what he might do. Still, the blond man continues to ride Nelson’s bus. Maybe it’s easier to say yes than no to a protector like that.

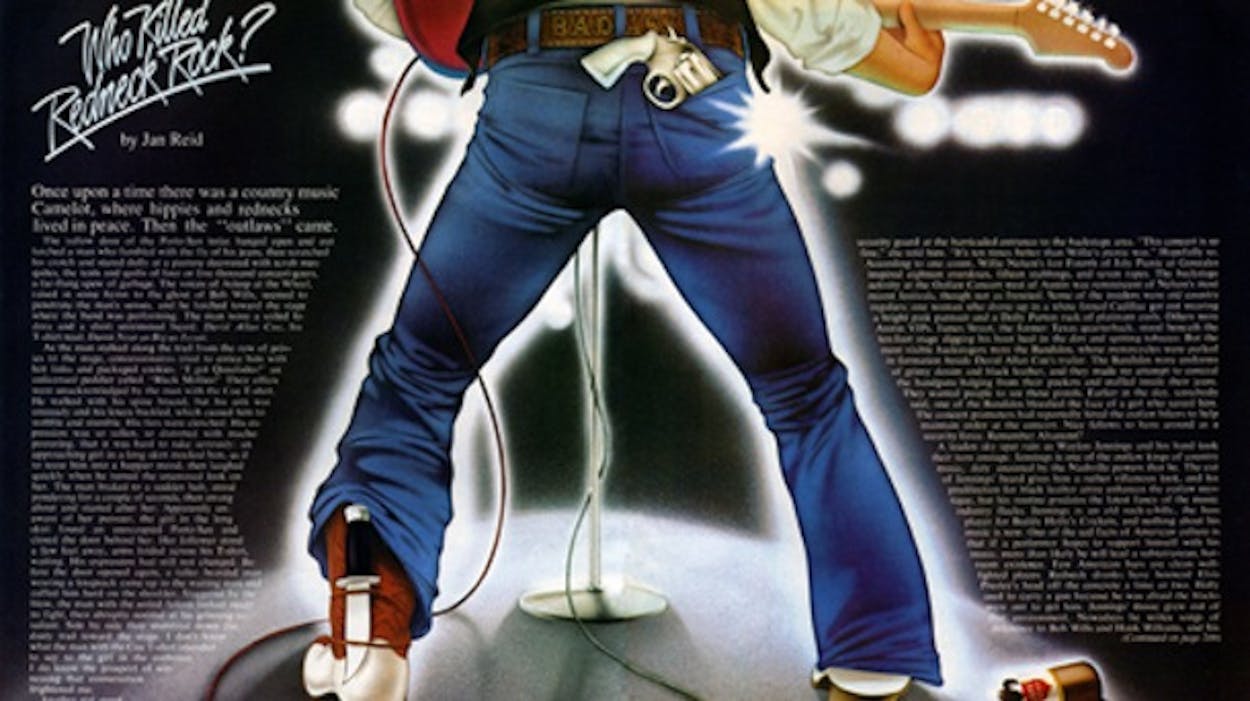

Outlaw country music is not just some misguided notion of the crowd. It’s a sales promotion hawked by the recording industry with Madison Avenue zeal. And it’s given birth to a new breed of popular performer. David Allan Coe didn’t flaunt a magnum in his hip pocket at the Outlaw Concert as he did at Gonzales, but as he moved around the stage during Nelson’s Outlaw Concert set his presence was no less forbidding. He was dressed like his Bandido buddies: stomping boots, a long earring that dangled from one ear, a sleeveless Levi jacket bearing Florida Outlaw colors and a small but prominent swastika. Coe has a neck the size of a small bull’s and he looks very much like the bad customer he claims to be. However, that night he didn’t add much to Nelson’s music. Mostly he banged a tambourine and crowded in on the microphones to sing backup. Being seen with the Man. Who is this hooligan, David Allan Coe, and what is he doing onstage with Willie Nelson? How did the good guys of country music come to wear black hats?

Half a decade has now passed since KOKE-FM in Austin introduced progressive country to radio programming. It quickly became the standard label for the country-rock-blues-gospel music blaring in the bars of Austin. The musicians who worked in those bars tended to associate professional misfortune with the big cities of the music industry, and in their music their flight to Austin became a symbolic retreat to the countryside. Sown deep in Texas tradition, sentimentally attached to the rural lifestyle, country and western was the handiest means of expressing that pastoral fantasy. The term progressive country encouraged instrumental departures from the Nashville straight and narrow, however, and implied a more positive set of lyrical values. The time had come to mend those fences torn down by the emotion-charged sixties, when relations between middle-class elders and anti-establishment youth were portrayed as a virtual state of war. Presuming to speak for his redneck audience, Merle Haggard fairly sneered the lines of “Okie from Muskogee.”

The rock ’n’ roll counterculture responded in paranoid fashion, accepting violent movies like Billy Jack, Joe, and Easy Rider as the gospel redneck truth. What a way to go, Dennis Hopper. Shoot the world the finger and get your head blown off: the death of a martyred saint. Progressive country insisted all that hostility was senseless. The differences of the past should now be reconciled. Understanding should be emphasized, not violence. Longhair and cowboy boots, beer and marijuana, rock ’n’ roll and country and western were no longer incompatible. Progressive country was a songwriter’s poetry of homecoming, celebration of nature, intelligent soul searching. Steve Fromholz took sympathetic strolls through the small towns of his youth. Jerry Jeff Walker exulted in the Hill Country rain. Michael Murphey lifted lines from the theology of Albert Schweitzer. Cosmic cowboys, riding point for Texas culture.

For a time there was a lot of boosteristic talk that Austin might challenge Nashville someday as a multimillion dollar entertainment capital. In terms of actual industry, Austin has never posed much threat to Nashville. Nashville studios produce roughly half the recordings released in the United States each year. Counting live-performance recordings, the long-play albums produced in Austin during the last five years number no more than a dozen. Viewed from a broader perspective, however, the feverish barroom activity in Austin lent credence to the notion that Nashville country and western was being driven in a new direction. Little storms of musical activity were brewing all around Nashville. Almost forgotten during the years of the Beatles, Southern rock ’n’ roll flowered again when Eric Claption enlisted the accompaniment of the Georgia slide guitarist Duane Allman for the agonized love songs of Derek and the Dominos. In Macon the Allman Brothers and Marshall Tucker developed a style of rock that owed most to the blues tradition of Southern blacks but also borrowed themes and riffs from country and western and gospel. Jimmy Buffet recorded vivid songs about the retirees and Cubans of Florida. Lynyrd Skynyrd of Alabama and ZZ Top of Houston contributed a crude strain of rock laced heavily with undertones of violence. All of that complemented the progressive country craze that seized Austin and then Dallas–Fort Worth. The underwriters of that musical activity were the rock recording industries of New York and Los Angeles. Nashville’s grip on the musical South was slipping.

Nashville is a conservative town, and the establishment of its music industry reflects that conservatism: one of Richard Nixon’s last hours of public glory was his appearance at the opening of the Grand Ole Opry auditorium. But ideology in Nashville country and western is always outweighed by acquisitive instinct and financial self-interest. Jennings and Nelson were frustrated recording artists in Nashville because they never quite got along with their bosses. They refused to conform in their music, and their standing—or at least potential—in the pop field enabled them to disregard accepted procedures. Jennings stepped on several toes in Nashville to get what he wanted from RCA executives in New York. Nelson signed with Atlantic in New York, then maneuvered a deal with Columbia that allows him to recruit and record artists on his own Texas label. Those were highly troublesome attitudes. For 25 years Nashville has been virtually the only place where country musicians can record. Jennings and Nelson weren’t originally perceived as outlaws by the corporate executives of country music. They were seen more as labor agitators. They were attracting a growing crowd of younger performers who played follow the leader both in their music and their approach to business. Nashville had effectively monopolized country and western music, and its money men didn’t want any overaged hippies rocking the boat. On the other hand, Nashville couldn’t afford to alienate all its musicians from Texas. Jennings, Nelson, and their motley followers had proved themselves capable of selling records. They appealed to the Southern rock crowd. Nashville’s money men have always envied the sales receipts of rock ’n’ roll.

Once a decision is made to market a new product, it has to be packaged and promoted. Assume, for example, that Waylon Jennings has recorded an album of Billy Joe Shaver’s rock-a-billy blues songs, using sidemen of his own choosing. One of their cronies, Tompall Glaser, produces the album. After the final mix, that music exists on its own terms, reeled on several hundred feet of recording tape or stamped flat on a phonograph. But now we have to package it. Shaver’s “Honky Tonk Heroes” is selected as the title cut of the album. For cover art we have a photograph of Jennings biting down on the filter of a cigarette while he repairs a broken guitar string and throws his head back to laugh. He’s surrounded by a rugged by jovial gang of barroom cronies. Nelson’s bass player, Bee Spears, stares at Jennings with apparent admiration. Billy Joe Shaver grins and grips a beer glass with the nubs of two partially amputated fingers on his right hand—major reasons why Shaver’s attempts to play the guitar are so ineffectual. Just a bunch of honky-tonkers, hanging out. Brown-tone the photograph to give it an old-time look and commission a worshipping Nashville flack to write the liner notes: “Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver are the first of the last real cowboys. Tompall Glaser is another one. . . . It ain’t easy being a cowboy in this day and time. But Waylon, Billy Joe, and Tompall get it done.”

Now that may seem merely banal, but lurking between those lines is the concept of the country music outlaw. If you’re trying to rope these disgruntled musicians with a common identity, you call them rebels . . . or mavericks. Now there’s a good Texas metaphor. Carry the Texas theme a little further. By authority of Waylon Jennings’ admiring flack, the Texas musicians are hereby granted sole rights to the romantic metaphors of the Old West. These honky-tonk heroes are not the singing cowboys who rescued maidens but kissed their horses in the folklore of the forties. In this new folklore the cowboys don’t punch cattle and they don’t even ride horses, because they were born too late. A range in the world where they live is an electric stove, and most of the words they hear are discouraging.

Only country music can keep the independent spirit of those frontier times alive. Cosmic is not the word for these cowboys. They’re life’s losers, like all of us, only these guys are going down swinging. If they had really been alive in the Old West, they would have been outlaws, sure as shootin’. That, in short, is the hype. Some observers credit Dave Hickey, a Texas writer who lives in New York, with original use of the outlaw metaphor in a Country Music article about Jennings. Whatever its origin, the idea has certainly caught on—not only in Nashville but in the New York and Los Angeles record industries as well. How many songs have we heard now about desperados and renegades? The most lavishly successful exploitation has been RCA’s Wanted! The Outlaws anthology of Nelson, Jennings, Glaser, and Jessi Colter. We are living in a time of outlaw hard sell.

In Texas, the last thing Nelson really needs is an outlaw identity. He may be a cult figure in these parts, but it’s still not hard to find a school board president who’ll tell you Nelson has always been a disreputable character, or a Sunday school teacher who shudders at the mention of Willie’s appearance on TV the other night. A subpoena to testify before a grand jury is by no means evidence of criminal activity—our system of law warns there should be no implication of that—but Nelson’s image was undoubtedly tarnished by his appearance on the periphery of the Joe Hicks drug-running trial in Dallas. The Gonzales County group who opposed Nelson’s last picnic called themselves Citizens for Law, Order, and Decency. On the other hand, as a recording artist Nelson is in the business of selling himself to the public, and the country music outlaw has sold well. The fad has made him a star. Nelson has won his fight with the Nashville establishment; during the recent awards ceremony of the Country Music Association, on three occasions Willie bounded to the podium in his Adidas to wave and laugh victoriously, “On behalf of me and old Waylon . . .”

Nashville may be forced to accept new gimmicks; Hollywood, on the other hand, is always in the market for them. During October a truckload of pumpkins overturned in downtown Austin, and stunt actors rode motorcycles through the lobby of the Driskill Hotel. Peter Fonda was making another low-budget movie called Outlaw Blues. According to advance summaries of the story line, Fonda, an inmate musician, plays first act for a country and western star who records a live album behind the Walls of Huntsville. Fonda’s performance winds up on tape, and the country star steals one of those songs. After he’s released by the warden, Fonda finds the country star and demands his songwriter’s share of the profits. Fonda shoots the Nashville star in the leg, flees the authorities on his motorcycle, then becomes an underground country star in his own right. Easy rider reborn as a redneck musician.

Austin musicians stood in line as extras on the set of Outlaw Blues, but few seem really comfortable with the role of the country music outlaw. In terms of their lifestyles, the concept is fairly ludicrous. Jerry Jeff Walker is one of the roughest tumblers of the lot, but he recently succumbed to the vanity of a nose job. In their careers some of the artists originally associated with progressive country have steered very clear of the outlaw crowd. Bobby Bridger has found a more congenial audience in Denver for his mountain-man and Lakota Sioux epics. The original cosmic cowboy, Michael Murphey, long ago moved to the Rockies and severed most of his ties with Texas music. Murphey’s performance as a pop star in the mold of John Denver has been disappointing, but you have to give him credit for knowing what he does not want to be associated with. The implications of outlaw chic are decidedly ugly. Now as much as ever, the redneck ethos is alive and well in the bars of Texas. Indeed, in some quarters it is the height of social fashion. The posturing toughs who congregate backstage bragging about jail-time and recalling favorite maimings have forgotten that it’s only music. Romantic metaphors can’t hurt you. Knives and bullets can.

The outlaw craze has focused attention on other songwriters whose lyrics are less esoteric than Murphey’s. Delbert McClinton’s music evolved in the squalid black bars of Fort Worth’s south side, and is still more indebted to blues than country and western. Through his first album, Victim of Life’s Circumstances, received most of its air play on progressive country stations, McClinton is bitterly critical of progressive country and its outlaw successor. “Whenever a bunch of bullshit comes in there’s a bunch of people that start playing bullshit music,” he told Jay Milner, editor of the new magazine Texas Music. “I’m sick and tired of somebody saying, ‘I’m a cowboy from Texas, gimme a longneck. I can’t drink nothing but longnecks.’ I’m sick of hearing that. It’s like the hippie cult before that and the surfin’ cult before that.” Yet for all his professed disavowal, McClinton’s first album was a pointed play to the outlaw country market. The hungover protagonist of one song learns from his jailer that he’s been incarcerated for “cuttin’ up some honky with that bone-handled knife.” Another boats that he’s known the special terror of being held at gunpoint. McClinton doesn’t question the ethics of songs that glorify violence. He plays his own hard-luck background for all it’s worth. He just thinks the outlaw image is all posturing.

Another songwriter we hear a lot these days is Charlie Daniels. A touring rock ’n’ roll performer in his younger days, for years he has been one of the most versatile and respected sidemen in the studios of Nashville. Often associated with the community of Macon rock ’n’ rollers, Daniels was recently hired back into the Nashville fold by a $3 million recording contract. Those are impeccable credentials in the outlaw country crowd. “The people who are into us are general admission people,” he told an interviewer from Dallas. “They don’t make a lot of money, they’re just what I call street people—the mainstream of the whole world—that’s what I’m talking about.” Daniels apparently likes to think of himself as a musical populist, but the lyrics of his most popular song, “Long Haired Country Boy,” read like the martial anthem of his generation’s poor white trash. He sings with the exaggerated drawl of a Gunsmoke villain; he crows exultantly that it took “half the cops in Dallas County to throw one coonass boy in jail.”

So we have an art form that extols violent behavior. Scrapes with the law are prestigious affairs. The sullen resentments of poor Southern whites are represented as positive values. Toss in racism, sexism, and a preference for scatological turns of phrase—you have described the music of David Allan Coe. In virtually every song he contrives some way of likening himself to that other ex-convict singer, Merle Haggard. He warns his audience that he’s never lost a fistfight—just in case anybody in the crowd is thinking of calling his bluff. Some of Coe’s songs have a vein of self-deprecating humor, a suggestion that he’s in on a fad, another Alice Cooper satisfying some kinky American need. His latest jukebox entry is entitled “Willie and Waylon and Me.” But Coe doesn’t want his authenticity questioned. He wants people to believe that he was in prison, that he picked up a mop wringer and bashed in the skull of an inmate who tried to sodomize him. It’s a reverse morality. Not only is Coe unashamed of his prison record; he offers it as his most legitimate credential. The outlaw pose is obviously important to David Allan Coe. It’s his badge of courage, his stamp of importance. He’s a honky-tonk hero, a performer in touch with the ugly mood of his crowd.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson

- Waylon Jennings