This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

All I know about the best man in my wedding is he didn’t exist.

Five days before John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, I got married for the second time. It was a Sunday, the day after I’d covered the SMU-Arkansas game at the Cotton Bowl, and Jo and I—who had known each other a good three weeks—were convinced by this romantic con man who called himself Richard Noble that we should drive to Durant, Oklahoma, and get married. Richard Noble personally drove us in his air-conditioned convertible. He paid for the blood tests and license. We used his 1949 Stanford class ring in the ceremony, and we drank a quart of his scotch and sang “Hey, Look Me Over” (“Remember when you’re down and out, the only way is up!”) on the way back to Dallas.

There was no such person as Richard Noble, and the Stanford class ring was bought in a hock shop. Whoever the man was who called himself Richard Noble had set up a bogus sales office in a North Dallas apartment complex inhabited mainly by airline stews and indomitable seekers and had managed to ingratiate himself with his personality, credit cards, liquor supply, and national WATS line. A month or so after the assassination, which I assume he had nothing to do with, Richard Noble vanished in the night. The FBI came around asking questions, and that was the last I heard.

A lot of bizarre people were doing some very strange things in Dallas in the fall of 1963, and Richard Noble was only one of them. Madame Nhu bought a dozen shower caps at Neiman-Marcus and tried to drum up support for the Diem regime in Saigon, even while her host in the U.S., the CIA, laid plans to assassinate Diem himself. Members of the American Nazi Party danced around a man in an ape suit in front of the Times Herald building. Congressman Bruce Alger, who had once carried a sign accusing Lyndon Johnson of being a traitor, went on television to denounce the Peace Corps as “welfare socialism and godless materialism, all at the expense of capitalism and basic U.S. spiritual and moral values.” Zealots from the National Indignation Committee picketed a UN Day speech by Ambassador Adlai Stevenson; they called him Addle-Eye and booed and spat on him and hit him on the head with a picket sign. When a hundred civic leaders wired strong and sincere apologies to the ambassador, General Edwin Walker, who had been cashiered by the Pentagon for force-feeding his troops right-wing propaganda, flew the American flag upside down in front of his military-gray mansion on Turtle Creek. There were pro-Castro cabals and anti-Castro cabals that overlapped and enough clandestine commerce to fill a dozen Bogart movies. Drugs, arms, muscle, propaganda: the piety of the Dallas business climate was the perfect cover. A friend of mine in banking operated a fleet of trucks in Bogotá as a sideline. Airline stewardesses brought in sugar-coated cookies of black Turkish hash without having the slightest notion of what they were carrying.

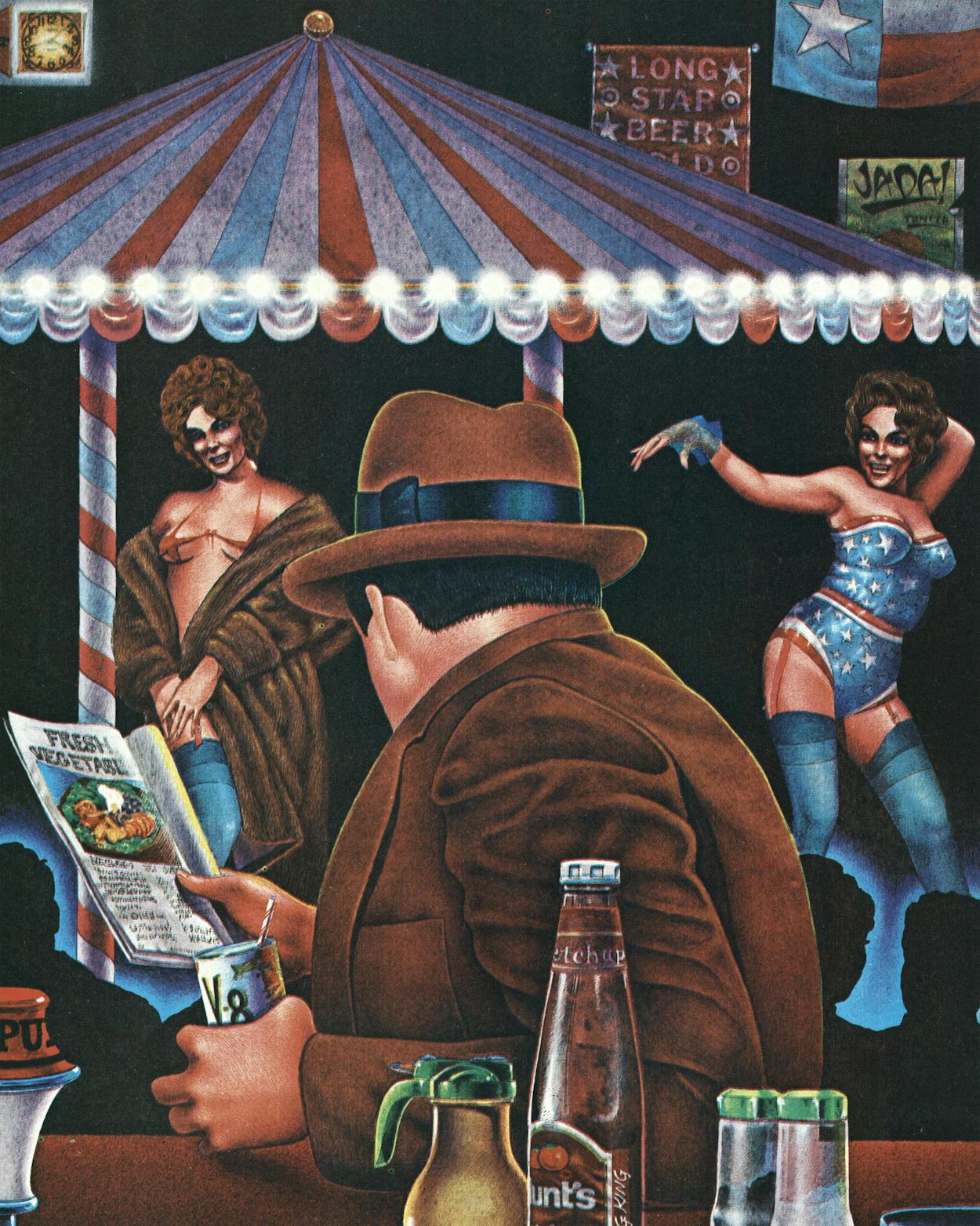

Jack Ruby was having one of his customary feuds with an employee of his Carousel Club, but this one was serious. His star attraction Jada claimed that she feared for her life and placed Ruby under peace bond. Newspaper ads for the Carousel Club during the week of November 22 featured Bill Demar, a comic ventriloquist—hardly Ruby’s style, but the best he could do.

And someone took a pot shot at General Walker in his own home. People said later it was Lee Harvey Oswald.

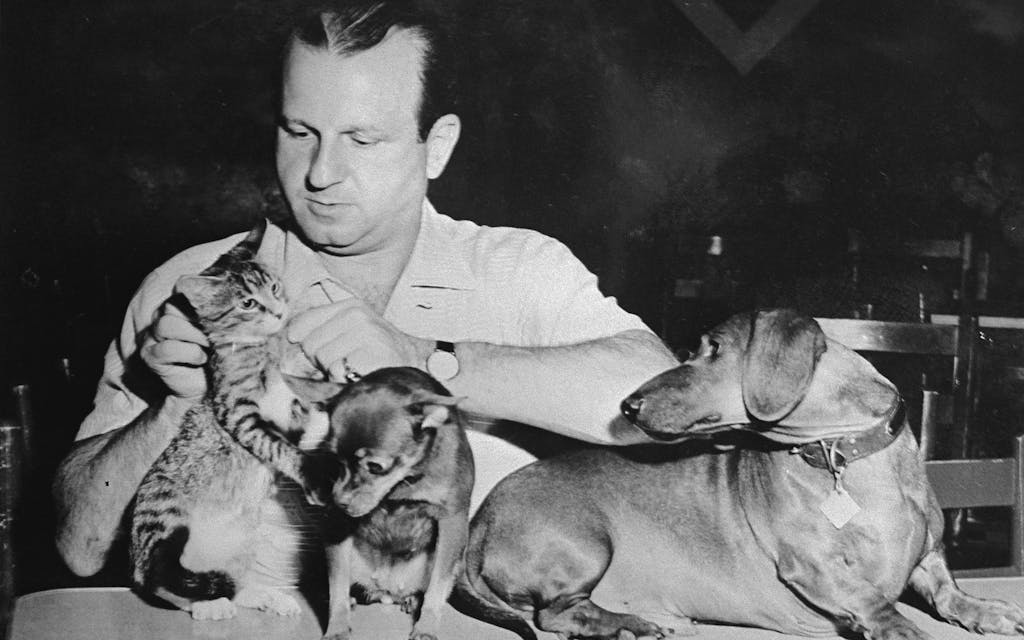

If there is a tear left, shed it for Jack Ruby. He didn’t make history; he only stepped in front of it. When he emerged from obscurity into that inextricable freeze-frame that joins all of our minds to Dallas, Jack Ruby, a bald-headed little man who wanted above all else to make it big, had his back to the camera.

I can tell you about Jack Ruby, and about Dallas, and if necessary remind you that human life is sweetly fragile and the holy litany of ambition and success takes as many people to hell as it does to heaven. But someone else will have to tell you about Oswald, and what he was doing in Dallas that November, when Jack Ruby took the play away from Oswald, and from all of us.

Dallas, Oswald, Ruby, Watts, Whitman, Manson, Ray, Sirhan, Bremer, Viet Nam, Nixon, Watergate, FBI, CIA, Squeaky Fromme, Sara Moore—the list goes on and on. Who the hell wrote this script, and where will it end? A dozen years of violence, shock, treachery, and paranoia, and I date it all back to that insane weekend in Dallas and Jack Ruby—the one essential link in the chain, the man who changed an isolated act into a trend.

Jack Ruby had come a long way from the ghettos of Chicago, or so he liked to think. He described the Carousel Club as a “f—ing classy joint” and patrons who challenged his opinion sometimes got thrown down the stairs. The Carousel was a dingy, cramped walkup in the 1300 block of Commerce, right next to Abe Weinstein’s Colony Club and close to the hotels, restaurants, and night spots that made downtown Dallas lively and respectably sinister in those times of official innocence. You can see more flesh in a high school biology class now than you could at any of the joints on The Strip in 1963, but that wasn’t the point. Jack Ruby ran what he considered a “decent” place, a “high-class” place, a place that Dallas could view with pride. “Punks” and “characters” who wandered in by mistake were as likely as not to leave with an impression of Jack Ruby’s fist where their nose used to be.

Cops and newspapermen, that’s who Ruby wanted in his place. Dallas cops drank there regularly, and none of them ever paid for a drink. Any girl caught hooking in his joint would get manhandled and fired on the spot, but Ruby leaned on his girls to provide sexual pleasures for favored clients.

Jack Ruby was a foul-mouthed, mean-tempered prude who loved children and hated ethnic jokes. He didn’t drink or smoke. He was violently opposed to drugs, though he maintained his own high energy level by popping Preludin—an upper—and it was rumored that he operated a personal clearing house for mob drug runners. He was involved in shady financial schemes, and the IRS was on his back. A swindler who called himself Harry Sinclair, Jr., told Secret Service agents that Ruby backed him in a bet-and-run operation. Ruby supplied cash and introduced Sinclair to likely victims. (H. L. Hunt was supposed to have been one.) If Sinclair won, he’d collect; if he lost, he’d write a hot check and split. Ruby got 40 per cent of the action.

Sex shocked and disturbed him, and that’s how Ruby had his falling out with Jada, who had been imported from the 500 Club in New Orleans so that the Carousel could compete with the much classier Colony Club (where Chris Colt was stripping) or Barney Weinstein’s Theatre Lounge around the corner, where you could catch Nikki Joy. Ruby was childishly jealous of the Weinsteins, who drove Cadillacs and Jaguars and took frequent trips to Las Vegas; and he assuaged his envy by drafting complaints to the stripper’s union, the Liquor Control Board, and the IRS, accusing the Weinsteins of whatever. Even the FBI, to its sorrow, knew of Ruby’s antipathy for the Weinsteins. Of all the Ruby rumors that have flourished and died through the years—that Ruby fired at Kennedy from the railroad overpass, that Oswald visited the Carousel Club a few days before the assassination—only the most current one, that Ruby was an informant for the FBI, seems to have much truth to it. Hugh Aynesworth, a Times Herald reporter who knew Ruby well, verified it: “In 1959 the FBI tried eight times to recruit Jack Ruby. They wanted him as an informer on drugs, gambling, and organized crime, but every time they contacted him, Ruby tried to get his competitors in trouble. ‘Ol’ Abe over at the Colony Club is cheating on his income tax. . . . Ol’ Barney at the Theatre Lounge is selling booze after hours.’ After a while the FBI gave up on the idea.” The Weinsteins, not surprisingly, considered Ruby a creep.

I first met Jada about a month before the assassination. Bud Shrake and I shared an apartment on Cole Avenue that autumn, and since we were both sportswriters, Ruby considered us favored customers. He invited us to the Carousel one night, and Shrake came home with Jada. We all became good friends, and when Jo and I got married a few weeks later, Jada gave us our first wedding gift—a two-pound Girl Scout cookie tin full of illegal weed she had smuggled across the border in her gold Cadillac with the letters JADA embossed on the door. Jada cleared customs with 100 of the two-pound tins in the trunk of her car. She was accompanied by a state politician (who knew nothing about the load) and wore a mink coat, high-heel shoes, and nothing else. The first thing she did at customs was open the door and fall out, revealing more than the customs official expected. That was one of Jada’s great pleasures, driving around Dallas in her mink coat and high heels, her orange hair piled high and the coat flaring open. It was a better act than the one Ruby paid for.

Ruby planted the story that Jada was trained in ballet, had a college degree in psychology, was a descendant of John Quincy Adams, and a granddaughter of Pavlova. Jada’s name was Adams, Janet Adams Conforto, but she hadn’t been inside a classroom since she ran away from a Catholic girls school in New York at age fifteen, and she couldn’t dance her way out of a donut. Her act consisted mainly of hunching a tiger-skin rug and making wild orgasmic sounds with her throat. As a grand climax Jada would spread her legs and pop her G-string, and that’s when Ruby would turn off the lights and the hell would start.

The other strippers and champagne girls hated Jada. She was a star and acted the part. The bus-station girls from Sherman and Tyler came and went—Ruby automatically fired any girl who agreed to have sex with him—but Jada treated Ruby like a dog. She called him a pansy and worse, and she spread word among the customers that the hamburgers served out of the Carousel’s tiny kitchen were contaminated with dog shit.

One night while Jada was ravaging her tiger skin, a tourist stepped up and popped a flashbulb in her face. Ruby threw the startled cameraman down the stairs. Jada popped her G-string about a foot, and Ruby threw her off the stage. All this took a few seconds, but for those few seconds Ruby was an absolute madman. Then he walked over to our table and said in this very weary, clear, huckster voice, “How’s it going, boys? Need anything?” I don’t think he remembered what had just happened.

On the morning of the assassination, Ruby called our apartment and asked if we’d seen Jada. Shrake said we hadn’t. “I’m warning you for your own good,” Ruby said. “Stay away from that woman.” “Is that intended as a threat?” Shrake inquired. “No, no,” Ruby apologized. “No, it’s just that she’s an evil woman.”

Unlike the other clubs on The Strip, the Carousel was strictly a clip joint where Ruby’s girls hustled $1.98 bottles of champagne for whatever they could get.

“We kept the labels covered with a bar towel,” a one-time Ruby champagne girl told me. The woman, who is now married to a well-known musician, went to work for Ruby when she was seventeen. “Jack would tell us to come on to the customers, promise them anything—of course he didn’t mean for us to deliver, but sometimes we did on our own time. The price for a bottle of cheap champagne was anywhere from fifteen to seventy-five dollars. We’d sit with the customer as long as the bottle lasted, drinking out of what we called spit glasses—frosted glasses of ice water. We worked for tips or whatever we could steal.

“Actually, Jack had a soft heart. He was always loaning us money and knocking the snot out of anyone who gave us a bad time. He liked that image of himself—big bad protector. He’d fire you, then ten minutes later break in on you in the john and demand to know why you weren’t on the floor pushing drinks. One girl there got fired about three hundred times.”

The only “decent” woman in Jack Ruby’s life was Alice Nichols, a shy widow who worked for an insurance company. He dated her on and off for eleven years. The reason Ruby couldn’t marry Alice, he told many of his friends, was that he had made his mother a deathbed promise that he wouldn’t marry a gentile. Ruby’s mother had died in an insane asylum in Chicago.

Ruby had the carriage of a bantam cock and the energy of a steam engine as he churned through the streets of downtown Dallas, glad-handing, passing out cards, speaking rapidly, compulsively, about his new line of pizza ovens, about the twistboards he was promoting, about the important people he knew, cornering friends and grabbing strangers, relating amazing details of his private life and how any day now he would make it big. He once spotted actress Rhonda Fleming having a club sandwich at Love Field and joined her for lunch. You could always spot him at the boxing matches. He’d wait until just before the main event, when they turned up the lights, and he’d prance down the center aisle in a badly dated hat and double-breasted suit, shaking hands and handing out free passes to the Carousel.

He was always on his way to some very important meeting, saying he was going to see the mayor, the police chief, some judge, Stanley Marcus, Clint Murchison. And every day he’d make his rounds—the bank, the Statler Hilton, the police station, the courthouse, the bail-bond office, the Doubleday Book Store (Ruby was a compulsive reader of new diet books), the delicatessen, the shoeshine parlor, radio station KLIF.

KLIF was owned by Gordon McLendon, whom Ruby once identified as “the world’s greatest American.” McLendon, who billed himself as “the Old Scotchman,” made his reputation recreating baseball games on the old Liberty Broadcasting System until organized baseball conspired to shut him down. The Old Scotchman would sit in a soundproof studio a thousand miles from the action he was describing, reading the play-by-play from the ticker, his voice shrill and disbelieving, while his sound man (Dallas’ current mayor Wes Wise was one of them) beat on a grapefruit with a bat and faked PA announcements requesting that the owner of a blue 1947 Buick please move his car out of the fire lane. Later McLendon pioneered the Top Forty music/news format, introduced a series of right-wing radio editorials, ran unsuccessfully for Ralph Yarborough’s Senate seat, and launched a one-man campaign against dirty and suggestive songs like “Yellow Submarine” and “Puff, the Magic Dragon.” The Old Scotchman, Jack Ruby liked to say, was his idea of “a intellectual.”

Ruby wasn’t a big man—five-foot-nine, 175 pounds—but he had thick shoulders and arms, and he was fast. He swam and exercised regularly at the YMCA, and was a compulsive consumer of health foods. He had an expression that dated from his street-fighting days in Chicago: “Take the play away.” It meant to strike first. He usually carried a big roll of money, and when he carried money he also carried a gun.

Hugh Aynesworth saw the many personalities of Jack Ruby as clearly as anyone. Aynesworth recalled a night at Ruby’s second club, the Vegas, when a drunk came in after hours with a bottle bulging from his inside coat pocket. Ruby took the man’s two dollars, showed him to a table, then smashed the bottle against the man’s rib cage. Another time Aynesworth encountered a dazed, bleeding wino staggering near the Adolphus Hotel. The wino had tried to bum a quarter from Ruby, who smashed him in the head with a full whiskey bottle. Yet at times Ruby could be embarrassingly sentimental.

“Ruby was a crier,” Aynesworth recalls. “I mean, he could go to a fire and break out crying.”

Aynesworth has been investigating the events of that week for twelve years and has concluded that the Warren Report is mostly accurate. Two nuts, two killings. “In Ruby’s case the conspiracy theory is totally ridiculous,” he told me. “Ruby would have told everyone on the streets of downtown Dallas. Ho, ho, ho, they asked me to help kill the President. Of course I’m not gonna do it.

Joe Cavagnaro, one of Jack Ruby’s best friends, made the same observation.

“Nobody would have trusted Jack with a secret,” he said. “He talked too much.”

Cavagnaro is the sales manager of the Statler Hilton, a neat, manicured, gregarious man who exudes the personality of downtown Dallas, but he was just a man in need of a friend when he arrived in 1955. Cavagnaro was eating at the Lucas B&B Restaurant next to the Vegas Club one night when Ruby sauntered in, said hello, and picked up the check.

“He was a fine person,” Cavagnaro said. “Much different than the picture you read. He had a big heart. He was good to people. Anyone down on his luck, he’d help them out to the point of excess. There was a policeman whose wife and kid were in an accident, he took over a sack of groceries. He’d read something in the paper about some poor family and he’d go to the rescue. Sure, he had a short fuse, but remember, he had to police his own business; otherwise they’d close him up. The vice squad was always hanging around his place. Some drunk would act up and Jack would remove him without the vice squad being aware it ever happened.”

Cavagnaro and Ruby had coffee at the Statler a few hours after the assassination. Ruby was extremely upset, and blamed the Morning News.

“He said it would be a cold day in hell before he placed another ad with the News,” Cavagnaro told me. “Jack was a true patriot. He was also a Democrat. He thought Kennedy had done a lot for the minorities. Just from a business standpoint, he said, something like that could kill a city.”

Did he say anything about killing Oswald?

“I think everyone in Dallas said something to the effect that ‘I’d like to kill that SOB.’ ”

But Ruby did it; that is the difference. What did Cavagnaro think when he heard the news?

“I thought, yes, Jack could do that. I’d seen him hit a guy once for insulting a girl. The guy practically left his feet and flew across the street.”

In the same block as the Statler Hilton and the Dallas police station, in a spot called the Purple Orchid, Ruby’s ex-champagne girl joined 80 million viewers of Ruby’s astounding crime on television. The girl turned to the bartender, who had also worked for Ruby, and she said: “Well, Jack’s finally gonna get recognized.”

Times Herald editorial page editor A. C. Greene and his wife had just driven home from church. Betty Greene ran ahead to answer the telephone, and when A.C. walked in the kitchen door she told him that someone had just killed the man who killed the President. He was someone who owned a downtown nightclub, Betty Greene said, bewildered. Oh, God, A. C. thought: Jack Ruby!

While Ruby was shooting Oswald, Jo and I were driving from Columbus, Ohio, where I had just met my new in-laws, to Cleveland, where the Cowboys were playing the Browns. The NFL was the only shop that stayed open that weekend. They claimed that it was a public service, and in retrospect I think they were right. Shrake met me at the press box entrance and told me what had happened.

“Jack Ruby!” I said. “Why not.”

“Why not,” Shrake said, shaking his head.

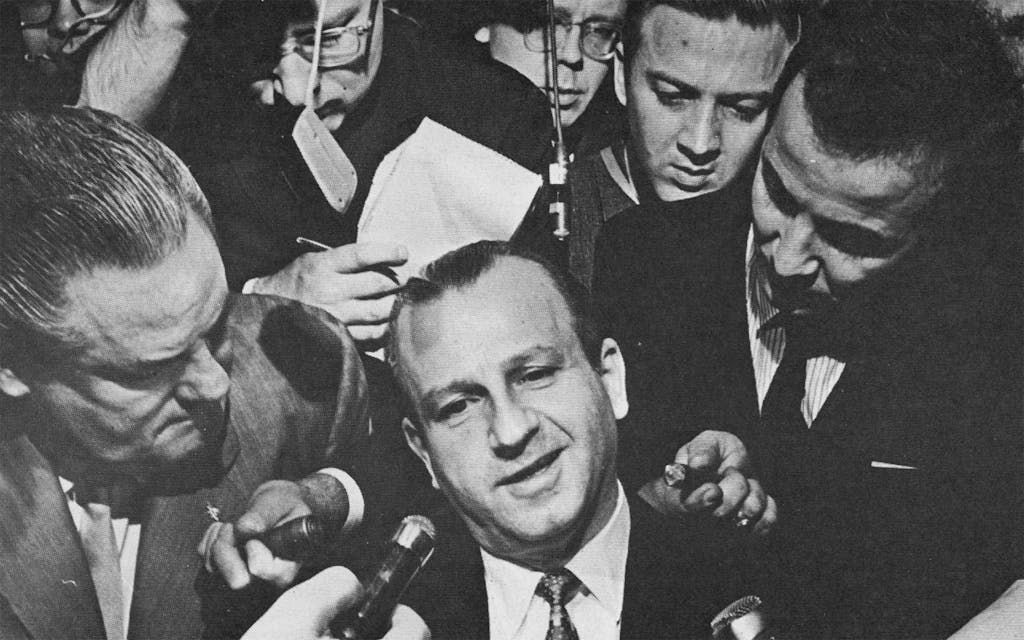

If you believe that Jack Ruby was part of a conspiracy, a “double cutout” as they say in the spy trade, then you must also conclude that the conspiracy involved dozens or even hundreds of plotters, including Captain Will Fritz of the Dallas police department. Time and events make Ruby’s role in a conspiracy almost impossible. Oswald was to have been transferred from the city jail to the county jail at 10 a.m.—that was a solid commitment Chief Jesse Curry made to his intimates among the press corps. If Ruby had been gunning for Oswald, if he had premeditated the crime that 80 million witnesses saw him commit, he would have been at the police station at 10 a.m. But he wasn’t. There were several reasons for the delay in transferring Oswald, but the main one was Will Fritz’s insistence on interrogating the suspect one more time in city jail.

Ruby knew when the transfer was scheduled. He had covered the event like a reporter on a beat: Parkland Hospital, the assassination site, the press conferences. He was always at the center of the action, passing out sandwiches, giving directions to out-of-town correspondents, acting as unofficial press agent for District Attorney Henry Wade—who, like everyone else on the scene, simply regarded Jack Ruby as part of the furniture. Twice during a press conference Wade mistakenly identified Oswald as a member of the violently anti-Castro Free Cuba Committee. The second time a friendly voice at the back of the room corrected the DA. “No, sir, Mister District Attorney, Oswald was a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.” The voice was Jack Ruby’s. How did he know that? Well, it was in all the news reports, but there is a more intriguing theory: an FBI report overlooked by the Warren Commission suggests that one of Ruby’s many sidelines was the role of bagman for a nonpartisan group of profiteers who stole arms from the U.S. military and ran them for anti-Castro Cubans.

Ten o’clock came and went, and still Oswald hadn’t been transferred. It was after ten when Ruby received a telephone call from one of his strippers who lived in Fort Worth. The girl needed money, she needed it right then. Ruby dressed and drove to the Western Union office in the same block as the police station. He couldn’t have missed the crowd lingering outside on Commerce and on Elm. At 11:17 Ruby wired the money. He walked up an alley, passed through the crowd, and entered the ramp of the police station, a distance of about 350 feet. He was carrying better than $2000 in cash (he couldn’t bank the money because the IRS might grab it) and his gun was in its customary place in his right coat pocket.

Three minutes after Ruby posted the Western Union money order, he shot Oswald.

If the world at large was shocked at that precise minute, consider the bewilderment of Jack Ruby as the Dallas cops pounced on him. What was wrong? Had he done something he wasn’t supposed to do? Didn’t everyone want to kill Oswald? What the hell was this?

“You all know me,” he said pathetically. “I’m Jack Ruby.”

Jack Ruby had to believe that he was guilty of a premeditated, calculated murder. The alternative—to admit he was crazy—was too awful to contemplate.

During the trial he told his chief attorney, Melvin Belli, “What are we doing, Mel, kidding ourselves? We know what happened. We know I did it for Jackie and the [Kennedy] kids. I just went in and shot him. They’ve got us anyway. Maybe I ought to forget this silly story that I’m telling and get on the stand and tell the truth.”

The silly story that Belli, Joe Tonahill, and other members of the defense team were attempting to pass along to the jury was that Ruby killed Oswald during a seizure of psychomotor epilepsy. Belli and Tonahill still subscribe to this contention.

“The autopsy confirmed it. Ruby had fifteen brain tumors,” Joe Tonahill told me. Tonahill, a huge, deliberate, friendly man, maintains the Ruby trial “was the unfairest trial in the history of Texas.” Judge Joe Brown, exhibiting a classic downtown Dallas mentality, appointed Dallas advertising executive Sam Bloom to handle “public relations” and overruled the defense on almost every motion. Ruby himself considered hiring a public relations man—or that’s what he wrote in a letter to his intellectual hero, Gordon McLendon.

“Jack Ruby needed help long before Kennedy came to Dallas,” Tonahill said. He was seated at the desk of his law office in Jasper, in front of a four-by-eight-foot blowup of Bob Jackson’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning photograph of the Oswald murder. “He was a big baby at birth—almost fifteen pounds. That could have had something to do with it. His mother died in an insane asylum in Chicago. His father was a drunk and was treated for psychiatric disorders. A brother and a sister had psychiatric treatment. Ruby tried to commit suicide a couple of years earlier. His finger was once bitten off in a fight. He had a long history of violent, antisocial behavior, and when it was over he wouldn’t remember what he had done. What provoked him? Maybe the flashbulbs—that’s a common cause in cases of psychomotor epilepsy—or the TV cameras, or the smirk on Oswald’s face.”

I asked Tonahill what he thought of Ruby as a person.

“He was a real object of pity,” Tonahill said. “Anytime you see a person overflowing with ambition to be someone, that person is admitting to you and the world that he’s a nobody. Ruby was like a Damon Runyon character—a total inconsistency.”

If Jack Ruby was not crazy when he gunned down Oswald, it’s a safe bet the trial drove him that way. Day after day in the circus atmosphere of Judge Brown’s courtroom, Ruby was forced to sit as a silent exhibit while psychiatrists called him a latent homosexual with a compulsive desire to be liked and respected, and his own attorneys described him as a village clown. He didn’t even get to tell his own story, and by the time the Warren Commission found time to interview him months later, Ruby was convinced that there was a conspiracy to slaughter all the Jews of the world.

“In the beginning,” Tonahill told me, “Ruby considered himself a hero. He thought he had done a great service for the community. When the mayor, Earle Cabell, testified that the act brought great disgrace to Dallas, Jack started going downhill very fast. He got more nervous by the day. When they brought in the death penalty, he cracked. Ten days later he rammed his head into a cell wall. Then he tried to kill himself with an electric light socket. Then he tried to hang himself with sheets.”

Ruby wrote a letter to Gordon McLendon claiming he was being poisoned by his jailers. Many Warren Report critics take this as additional evidence of a conspiracy. If someone did poison Ruby, it was a waste of good poison. An autopsy confirmed the brain tumors, massive spread of cancer, and a blood clot in his leg, which finally killed him.

The trial of Jack Ruby may have been one of the fastest on record. The crime was committed in November and the trial began in February. “The climate never cooled off,” Tonahill said. “He was tried as it was peaking. There was this massive guilt in Dallas at the time. The only thing that could save Dallas was sending Ruby to the electric chair.”

Though there are unanswered questions in his mind, Tonahill supports the conclusions of the Warren Report.

“If there was a conspiracy, and it was suppressed, it had to involve maybe a million people. That’s a bunch of crap.

“The worst mistake the Warren Commission made was yielding to Rose Kennedy and suppressing the autopsy report. There was something about Kennedy’s physical condition the family didn’t want made public. I don’t know what it was. Possibly a vasectomy—there was a story he had a vasectomy after the death of his baby. Being good Catholics, the Kennedy family wouldn’t have wanted that out.”

Once close participant in the bizarre happenings of Dallas who isn’t satisfied with the Warren Commission investigation is Bill Alexander, the salty, acid-tongued prosecutor who did most of the talking for Henry Wade at the Ruby trial. Alexander and former state Attorney General Waggoner Carr both urged the commission to investigate FBI and CIA personnel for information linking the agencies to Lee Harvey Oswald. There is no indication that such an investigation took place.

“I’m in Washington telling the commission to check out this address I found in Oswald’s notebook, in his apartment, the day of the killing,” Alexander recently told the Houston Chronicle. “None of those Yankee hot dogs are paying any attention to me.

“So I say ‘Waggoner, c’mon, let’s get a cab.’ We jump in and tell the driver to take us to this address. We get there and what do you think it is? The goddamn Russian Embassy. Now, what does that tell you?

“To this day, I don’t think anybody from the commission followed that up.” Although Alexander, known to members of the press as “Old Snake-Eyes,” was the main reason Henry Wade got all those death penalties that the leaders of Dallas were convinced would deter crime, he is no longer on the DA’s staff. Shortly after his infamous declaration that Chief Justice Earl Warren didn’t need impeaching, he needed hanging, Alexander resigned to enter private practice.

When I telephoned Alexander for an interview, he told me he didn’t want to talk about the assassination.

“I’d like to kick the dogshit out of every Yankee newspaperman, club the f—ers to the ground,” he said. You can still see them, right up to this day, hanging around the Book Depository,” Alexander went on. “Fat-ass Yankees in shorts and cameras getting the roofs of their mouths sunburned. A carload of Yankees pulled up to my friend Miller Tucker and said [Alexander slipped into an Eastern accent], ‘Officer, where did Kennedy get shot?’ Ol’ Miller taps the back of his head and says ‘Right here, friend, right here.’ ”

That afternoon I met Alexander in his law office and he told me about his Manchurian Candidate theory.

“I worked a solid two years on this,” he began. “I read the entire twenty-six volumes of the Warren Report just to protect myself, and tracked down every lead I could get my hands on, and I don’t have any evidence that anyone acted with Oswald.

“Now,” he said, raising a finger and slipping into third person singular so that it would be clearly understood he was speaking hypothetically, “Who knows how a person has been brainwashed—motivated—hypnotized?

“A man is cashiered out of the Marine Corps—he moves to Russia—he marries the niece of the head of the OGPU spy school—he stays a certain amount of months, then turns up at the American Embassy and says, ‘King’s X, fellows, I want to go home. Do you think you people might could pay my way back to New York?’ Wouldn’t somebody debrief that man? Hell, the FBI knew he was in New Orleans. They sent his folder to Dallas before the assassination.

On the other hand, Alexander has not the slightest doubt that Ruby acted alone in a legally sane, premeditated manner. Alexander and Dr. John T. Holbrook were among the first to question Ruby after the shooting.

“I’m paraphrasing now,” Alexander said, “but it was like he wanted to open the Jack Ruby Show on Broadway, get a TV show, write a book. He asked me if I thought he needed an agent.”

Alexander spat tobacco juice in a can and said: “Jack Ruby was about as handicapped as you can get in Dallas. First, he was a Yankee. Second, he was a Jew. Third, he was in the nightclub business.

“That’s horseshit about him being a police buff. He didn’t think any more of a policeman that he did a pissant. It was just good business. The vice squad kept plus and minus charts on the joints ’cause the licenses came up for renewal each year. The vice squad can kill a joint if they get in the wrong mood. Who wants to drink beer with a harness bull looking over his shoulder?

“Quit kidding me about how much Ruby loved people. Or how much he loved the Kennedys. Hell, where was he while the motorcade was passing through downtown? In the goddamn Dallas News, placing an ad for his club.”

The ex-prosecutor sat back and sighed.

“It’s a real experience to see how real, factual history can be distorted in ten years so that people who lived it can’t recognize it.”

And the end of all our exploring

—T. S. Eliot, from Little Gidding

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

On a warm day twelve years removed from that time of Ruby and Oswald, my son Mark and I walk the streets of downtown Dallas and know the place for the first time.

The Blue Front where you could eat the world’s best oxtail soup and watch Willie sweat in the potato salad is gone. The Star Bar is gone. Hodges, Joe Banks, the Oyster Bar, the musty little book stores with their dark volumes, the mom and dad shops, the smell of pizza, of chili rice, of peanut oil, of stale beer, of perfume, lost now in the tomb of our memory. What you smell twelve years later is concrete. What you see are the walls of a glass canyon.

The corner of Commerce and Akard, which used to bustle with beautiful women in short skirts and quick men with briefcases, is nearly deserted, except for a few Hare Krishnas and some delegates to the Fraternal Order of Eagles. The Carousel, the Colony, the Theatre Lounge, the Horseshoe Bar, the whole Strip has been leveled and turned into a gigantic parking lot for the invisible occupants of the glass skyscrapers. The big department stores and the theaters and the good restaurants have gone to the suburbs. Twelve years ago you could have dropped a net sixteen blocks square from the Republic National Bank tower and have been fairly sure that you had caught a quorum of the Dallas oligarchy. There is still a feeling of affluence, but the vortex of power has moved to the suburbs, out Stemmons, out Greenville, out Northwest Highway, out to Old Town—whatever Old Town is.

There are blacks on the city council, and the mayor is a former grapefruit hitter for the Old Scotchman. The Old Scotchman long ago sold KLIF and is seldom seen anymore; he is a Howard Hughes figure, dabbling, so it is said, in multinationals and worldwide real estate. When the sun disappears behind the canyon walls, what you see in downtown Dallas is blacks with mops and brooms, waiting for an elevator. Slack-faced office workers wait for a bus in front of the old Majestic Theater, and black hookers with beehives appear to show the Fraternal Order of Eagles the sights.

I wonder: could there be a Jack Ruby in 1975? Where would he go? What would he do? The Dallas Jack Ruby knew is gone.

That Dallas was a city of shame, but it wasn’t a city of hate. It was ignorant, but it wasn’t mean. Its vision was genuine and sincere, but it had the heart of a rodent. In the subterranean tunnels of those proud spires of capitalism and free enterprise crawled armies of con-men and hustlers, cheap-shot artists and money changers, profiteers and ideologues, grubbers, grabbers, fireflies, eccentrics, and cuckoos. Dallas was just like every place else, except it couldn’t admit it. It was not Lee Harvey Oswald and the murder of John F. Kennedy that proved what Dallas was really like, but Jack Ruby and the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald.

We drive out Turtle Creek past General Walker’s prim gray fortress. On the front lawn, a crude, hand-lettered marquee said DUMP ESTES, a reference, I suppose, to the Dallas superintendent of schools who apparently wasn’t resisting integration fast enough. Like downtown Dallas, the General is quieter these days. Ken Latimer, a resident actor at the Dallas Theater Center, tells us, “General Walker and his people used to picket us fairly regularly, but they’ve been quiet for some time now.” Latimer played the lead in the DTC production of Jack Ruby, All-American Boy, a drama that attempted without much success to answer the question: Was Jack Ruby a typical American?

“Ruby wanted to be liked, to be respected, to be successful according to the value system of our society,” Latimer says. “He was a cheap success, but in his own mind he had class. Violence was admissible to his system—toughness—let no one push you around.

“You asked me was it the climate of the times that made Ruby do what he did? No, Jack Ruby would do the same thing today.”

We talk to stripper Chastity Fox, who played the role of Jada. Chastity had never met Ruby or Jada; she was a junior in an all-girls Catholic school in Los Angeles when Kennedy was assassinated. She is fascinated that I had known them and asks me four questions for every one I ask her. Chastity looks something like Jada, except better.

She refused to do Jada’s tiger-rug hunch in the play. “Her show was nasty,” Chastity says. “I’m more of a dancer.” Chastity’s best act is belly dancing, a subject she teaches at the University of Texas at Arlington. But like Jada she’s come through some tough places—she remembers stripping in the Lariat Bar in Wyoming while a three-piece Western band played “Won’t You Ride in My Little Red Wagon?”

“The club action in Dallas is different now than it was in Ruby’s time,” Chastity says. “There are still a few clip joints like Ruby ran, and there are three, maybe four, traditional strip places where you can go watch a show and not get hustled. The big thing now is topless. The traditional strip show—we call it parading—is dying out. It’s sort of sad. It is an American tradition, but it dates back to the Forties and Fifties when you couldn’t see ass or boobs walking down the street.”

Although she never knew Jack Ruby, Chastity had heard of him for years from her agent, Pappy Dolsen. Pappy was one of Ruby’s contemporaries, an old-time club owner and booking agent, a gentleman tough from a truly tough time. Pappy had told the story many times how Ruby telephoned him the day before Oswald was killed and said: “I know I did you wrong, Pappy, but I’ll make it up to you. I’m going places in show business, and when I do, you’re going with me.”

Pappy has had a heart attack and is in the intensive care ward at Baylor Medical Hospital, but Chastity shows us a letter that Ruby had written to Pappy years ago. It said:

We regret, at this time, we are unable to book the “act” you have for us—I’m sure its as wonderful as you mention but the price is too f—ing high. Hoping to confront you on a more senseable base in the future. I remain.

Jack Ruby

There is one more thing to do. Mark was six years old, a Dallas first-grader when Kennedy was murdered. He doesn’t remember much of it. But there was an article in Look, written by a Fina Oil Company executive named Jack Shea, which mentioned that at one public school in Dallas, children cheered the news of the assassination. Jack Shea was a good Catholic and a top-level businessman, but his gut feeling that Dallas was big enough to hear the truth from one of its own was a serious miscalculation. Shea was fired. He is now a partner in a Los Angeles ad agency.

Jo and I named our son Shea after the Fina executive, and I was curious to read the article one more time. Funny, I had never told Mark or his sister Lea how Shea got his name. I hadn’t thought about it for a long time. Too many things had happened.

Twelve years ago, when the first announcement that the President had been shot was broadcast over the PA system at Richardson Junior High School, Gertrude Hutter, an eighth-grade teacher, began crying. Bob Dudney, who is now a reporter for the Times Herald, recalled the moment. She turned her back long enough to compose herself, then addressed her class with these prophetic words:

“Children, we are entering into an age of violence. There is nothing we can do about it, but all of us must stay calm, and above all, civilized.”