You really ought to see Bob Dunn’s Hawaiian-style lap-steel guitar. In 1934 Dunn was playing with western swing founder Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies when he attached a small metal pickup to his instrument, plugged it into an amp, and became arguably the first country musician to play electric guitar. Emulating the tailgate trombone of Jack Teagarden, Dunn churned out boozy, feedback-laden licks so incredibly loud, humorous, and dissonant that they still sound radical today.

Thanks to the new Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, which opened in Nashville in May, you can see one of Dunn’s gems. The instrument was discovered in the attic of the old Crystal Springs dance hall in Fort Worth, where Brown appeared regularly. It is so tiny it will leave you wondering how such a small guitar could have created such big sounds. Even more impressive, the lap steel shares a case in the hall’s special Texas exhibit with one of Flaco Jimenez’s red Hohner button accordions. That may not seem remarkable at first glance, but any museum that forces music fans to consider the relationship between conjunto and country is making connections too long overlooked. And that’s exactly what the new hall of fame does.

This downtown museum, run by the Country Music Foundation (CMF), is a huge improvement over its predecessor. The CMF opened the old hall in 1967 as Music City’s monument to itself: The cramped space equated the history of country music with the history of the Nashville industry. Its holdings were little more than a random collection of artifacts—some of them, admittedly, quite impressive and worthy of their inclusion in the new facility—and they certainly didn’t add up to a coherent picture of the music, musicians, and fans.

The new $37 million, four-story building boasts 40,000 square feet of exhibit space, and its view of country music is broad-minded enough to include, for example, Jason and the Scorchers and other alternative-country artists that are generally more popular with rock audiences than with country fans. And like a good country song, this museum tells a story, about a working-class music that sprang up in various guises over much of the nation, was consolidated in Nashville after World War II, and then spread out again to achieve worldwide popularity. Even the building’s architecture does its part. Depending on your angle, the limestone-brick-and-glass structure looks like a piano, a railroad station, or the fins of a Cadillac. Viewed from the air, it’s shaped like a treble clef, and the rotunda is designed to resemble a stack of records and CDs.

Most important, the hall does Texas proud. Artists from the state figure throughout the permanent exhibits, and Texas musicians are the subject of a special display that will run through May. Beginning August 18, when former Bob Wills fiddler Johnny Gimble and his band Texas Swing perform, the museum will also stage a Celebration of Texas Music series. Though most of the events remain in the planning stages, organizers hope to include a film festival, concerts featuring various songwriters, and a scaled-down version of the Kerrville Folk Festival.

“We hope people come away with a real sense of the musical richness of this one state, because country music in Texas means so many different things,” says content curator Daniel Cooper. Though Cooper laments that even the new museum doesn’t have the space to tell the full story of Texas’ contributions to country music, the special exhibit suggests the state’s varied styles by smartly juxtaposing seemingly unconnected items in a single glass case. Hence, Dunn’s rude steel and Jimenez’s delicate accordion. Another eye-opener features two prominent songwriters, old-school Cindy Walker (“You Don’t Know Me”) and hard-edged Townes Van Zandt (“Pancho and Lefty”). The latter is represented by his composition book, which is open to the lyrics of “Maria” and some simple line drawings that suggest that songwriting was indeed his true calling. Walker contributed the ancient, portable Royal typewriter on which she completed the lyrics to her songs. It is painted pink and covered with flowery decoupage. You couldn’t ask for a better symbol of her starry-eyed, fairy-tale romanticism. Nor could you more dramatically illustrate the differences between the two songwriters.

There are plenty more treats like that—western swing bandleader Adolph Hofner’s red Pearl Beer tie, Todd Oldham’s outrageous black outfits worn by the Dixie Chicks when they picked up their Grammys in 1999—but the other true standout is a portfolio of photographs by singer-songwriter Butch Hancock, which shares two walls with candid backstage shots by Scott Newton of Austin City Limits. Hancock’s West Texas landscapes almost invariably have natural elements—floodwaters, tornadoes, and such—at their heart, with fence posts, barbed wire, and windmills emerging from the ground like skeletons. This, Hancock’s photos say, is where his songs come from, as well as those of Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Terry Allen, Al Strehli, and so many others; this is the unforgiving environment that shaped both the rough, leathery ethos of Waylon Jennings and, somehow, the cheery rock and roll of Buddy Holly.

When the special Texas exhibit ends, some of the items will be eligible for inclusion in the main hall that occupies the second and third floors of the museum. In that area, placards identify the displays and give the birthday and state of each artist. There’s no doubt how Texas rates. Already a hugely disproportionate number of the musicians hail from here, beginning with Amarillo fiddler Eck Robertson, who recorded the first country single in 1922. It is hard to walk these two floors without concluding—correctly, I might add—that Texas had as much to do with shaping each stage of country music as any other state.

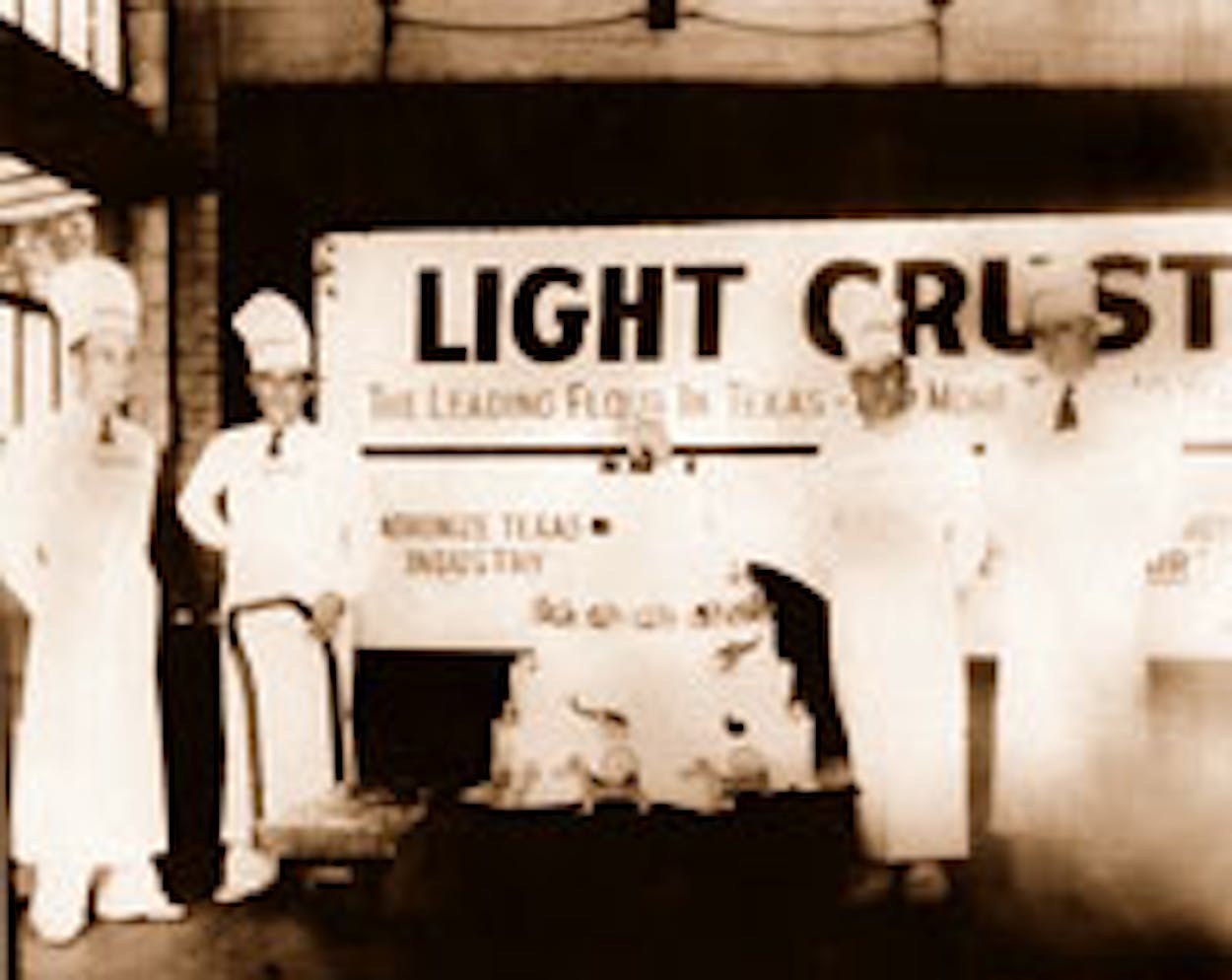

At the same time, the western swing section—with its great photo of original Light Crust Doughboys Milton Brown and Bob Wills wearing bakers uniforms advertising their sponsor, Burrus Mill and Elevator Company—demonstrates how country has always been inextricably bound with commerce. Rare film footage of Wills and his Texas Playboys horsing around outside their bus and playing a dance as the horn men fan their instruments with their hats also conveys just how much pure fun Wills’s music was, and what a relief it provided from the everyday woes of the Depression. Likewise, succeeding generations of Texans had a lot to do with injecting show biz into the music; just look at Tex Ritter’s silver-plated saddle, songwriter Ted Daffan’s spiffy black Western suit, and Hank Thompson’s red-white-and-green boots inspired by his 1948 debut hit “Humpty Dumpty Heart” (at the top of each boot, a red heart sits precariously on a brick wall; on the foot of each boot, the heart has fallen and split in two). Texans also led the way in the reaction against show biz; witness Willie Nelson’s grubby sneakers and headband. Of course, Texans didn’t control country music any more than did Tennesseans; other regions (such as Southern California) also win more prominence under the CMF’s ecumenical approach. Again, this is as it should be.

Best of all, the museum invites—no, demands—that visitors participate rather than view passively; many of the displays feature interactive elements, and you can even take country dance lessons as part of the tour. I found little to complain about: The live music in the conservatory echoes obnoxiously and the embossed explanations on some of the all-glass display cases are difficult to read. But for the most part, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum strikes a pleasing note, both in its overview of Texas and in its overall history of the music. In doing so, it shows that the state and the music are inseparable.