This is a Horatio Alger story of sorts about Leonel Castillo. I say “of sorts” because Horatio Alger wrote nineteenth-century rags-to-riches sagas and Leonel Castillo, at age 37, is making the unspectacular salary of $14,800 a year as Houston’s city controller and still buys some of his clothes at the Salvation Army. But he doesn’t care too much about money, and he can boast that he has the largest electoral constituency of any Mexican-American politician in Texas. Because he is a liberal Democrat who has campaigned much of his adult life for the civil and political rights of blacks as well as Chicanos, he enjoys an impressive reputation in certain national circles. The reputation brings him invitations like one last month to meet with McGeorge Bundy of the Ford Foundation, which is wondering what it should do about the fact that sometime in the next decade Hispanic Americans are expected to overtake blacks as the most populous minority group in this country.

In Texas, Mexican-Americans already outnumber blacks, the two groups representing 17 per cent and 11 percent respectively of the state’s approximately 12 million people. These figures alone encourage some of Castillo’s strategists to suggest that by the 1980s the first member of an ethnic minority group will be elected to statewide office, probably some secondary post like state treasurer or comptroller of public accounts- and, of course, they are betting on Castillo.

Still, in these times of an apparent slide to the political right and a return to consensus politics, ambitious minority leaders are facing a basic dilemma: to succeed they must move away from acting as advocates for their political base in order to appeal to a larger constituency. The moment they do, they are inevitably barraged by accusations that they have “sold out.” Yet it is significant that someone like Charles V. Hamilton, who collaborated with black activist Stokely Carmichael in writing the book Black Power in the Sixties, is now advocating what he calls “deracialization” of politics. Issues should be advanced, the theory goes, not simply because they are important to blacks, but because they matter to a much larger, much more amorphous group of which blacks are only a part. Leonel Castillo is in the forefront of this return by minority politicians to the political mainstream; he is a liberal making his reputation as a fiscal conservative.

Of course, before he can win a statewide race, he must first be known statewide and be able to raise a lot of money. Two years ago Castillo came surprisingly close to being elected chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee, a position that would have helped him greatly with both requirements. He wants to run for party chairman again this September. A couple of key votes at the June State Democratic Convention in Houston demonstrated that Governor Dolph Briscoe’s handpicked party chairman, conservative Calvin Guest of Bryan, will be far more vulnerable than he was in 1974, when Castillo got about 42 per cent of the vote. Indeed, it’s clear that if the Jimmy Carter supporter and uncommitted and liberal delegates unite in September as they did in June, Castillo or any other candidate they support will win. (Castillo originally favored Sargent Shriver for president but signed into the June State Convention as a Carter delegate.) But whatever happens in September, you are likely to see and hear more of Leonel Castillo before the decade is out.

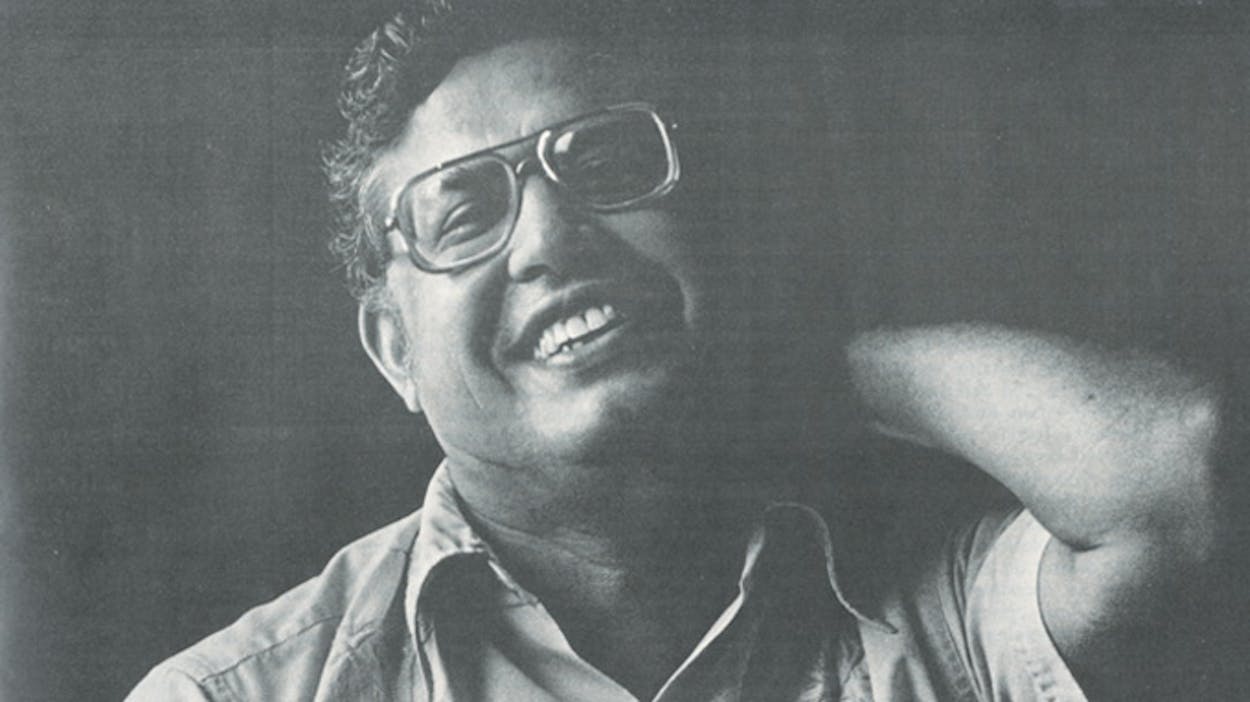

In high school they called him Lone, a nickname that persists today among family, friends, and acquaintances. It’s short for Leonel, a name still often mi pronounced

Lionel, but it was partly inspired by the funny, goggle-like glasses he had to wear because of his extreme myopia when he played for the Kirwin Buccaneers, the football team of the Catholic high school he attended in Galveston. Those glasses made him something of a masked man, so Lone was a natural, the Lone Ranger then being a popular television hero. The tag fit in another way, too: a studious, shy, gangling kid, he was a bit of a loner.

The youngest of four children of a union dock worker on the Galveston waterfront, he wore those round wire-frame glasses that were a badge of poverty, not fashion, in the Fifties, and he tended toward gentle and aesthetic pursuits. He played the piano for a while until his older brother Seferino convinced him that was sissy and steered him to an acceptably macho alternative, lifting weights with the guys at the YMCA. Still, he tended to keep his distance from the group. John Sanchez, a Galveston longshoreman who used to lift weights with the brothers Castillo, recalls that after weekend football games he and Seferino would go out to drink -“and Lone would go back to his books. I think that’s why he had trouble with his eyes, he read so much.” Castillo remembers being horrified by the Aztec Bar, then a Mexican-American hangout near his family’s east end home and a notorious bucket of blood. He still doesn’t do much drinking except for an occasional beer. When a persistent host recently asked if he could “put something in” the Coke Castillo had requested, he responded, “Ice.”

Castillo’s political awareness first blossomed at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio. As a political opponent’s dossier noted later, in 1961 Castillo was a member of Students for Civil Liberties, described by the opponent as a group that “joined forces with Armed Forces personnel to force a downtown movie theater to eliminate segregated seating.” Activism like Castillo’s helped make San Antonio the first major city in Texas to open its hotels and public facilities to Negroes. His efforts were an early expression of his enduring efforts to form alliances between blacks and browns, a commitment that later helped land him a seat on the board of the black-dominated national Urban Coalition, balancing his more predictable place on the board of the Mexican-American Legal Defense and Education Fund and the National Council of La Raza (a Hispanic group unrelated to the Southwest’s radical Raza Unida Party). His inclinations naturally led him to work as a political foot soldier in the Viva Kennedy organization, which was set up to mobilize the Mexican- American vote for John Kennedy in 1960. That same year he served as president of the college’s student government. After he graduated cum laude with a B.A. in English from St. Mary’s in 1961, Castillo responded to JFK’s call to idealism and joined the first wave of Peace Corps volunteers. He was assigned to the Philippines and soon rose to a staff position in which he supervised 85 volunteers.

Peace Corp officials were impressed by his ability to master obscure Philippine dialects, but Castillo says he found many of the words little different from the mutations of Spanish he had heard used in Galveston’s east end or South Texas. During his four-year tour, he married Evelyn Chapman, daughter of an American contractor and hi Chinese-Filipino wife, in whose large home Castillo was a boarder. Next came a short stint as a director of the Peace Corps Philippine training program at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By that time the former scholar was committed to politics, and he quit the Peace Corps in the fall of 1966 to seek a master’s degree at the University of Pittsburgh in community organization.

The year in Pittsburgh was austere for the Castillos. The family (a daughter had been born in the Philippines and a son was on the way) took its meals off a cardboard box that doubled as a dining room table. Castillo bought a $14 pair of hair clippers and Evelyn began giving him haircuts-as she does today. Then as now they bought day-old bread. “Basically we live very cheaply,” Castillo says. “We don’t spend money to eat out. We don’t spend money on drink. We don’t belong to any country clubs. I have a couple of suits bought in stores now, but before them I got almost all my suits at Goodwill or the Salvation Army. Five dollars for a suit. Twenty-five cents for a shirt.” And, as his political enemies are quick to point out, $72,000 for a house. But more about that later.

Castillo took a job in Houston in 1967 as a supervisor for a neighborhood center’s day care program. A year after that he quit to direct a couple of programs to train the hard-core unemployed. Almost immediately he plunged into activist Mexican-American politics. Six months after his return to Texas he went to a conference on Mexican-American affairs in El Paso attended by then Vice President Hubert Humphrey and three members of Lyndon Johnson’s cabinet. Castillo caught some national attention because he called for blacks and browns in the Southwest to join in a vigorous effort to lower the voting age to 18. The two minority groups had median ages much lower than those of Anglos, he argued, and stood to pick up proportionately more votes. In 1969 he surfaced as a member of an ad hoc group called Citizens for an Effective Housing Code. About the same time he began to involve himself with an interracial committee pressing the conservative Roman Catholic bishop of the Houston-Galveston diocese. Ln June 1969, the group taped a list of demands to the door of the chancery. The core of their complaint was that the church was doing next to nothing either to promote integration or to help meet the secular needs of its poor parishioners. That September Castillo began publicly needling the Houston school districts over the inferior education Mexican-American children were receiving. In March 1970, Castillo’s persistent but diplomatic hectoring of the church paid off, at least for him personally: he became head of the Catholic Council on Human Relations, charged with creating and coordinating social action projects within the diocese. He gave grant-writing seminars to show Mexican-Americans and others how to apply successfully for available federal funds to start or finance local programs.

Looking back with the advantage of hindsight, it’s easy to say now that Castillo stood out, that he was obviously on the way up. But Houston was full of ambitious, aggressive young politicians, all of them comers, all of them leading this board or that group, all of them looking for a break. Castillo was the one who got it.

On August 25, 1970, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals handed down an order approving the integration of white and black schools in a controversial pairing plan. What made it controversial was that the enrollments at the paired white schools happened to be overwhelmingly Mexican-American. A loose confederation of Latin groups called the Mexican-American Education Council (MAEC) hastily formed to protest the order, and its more volatile and politically inexperienced young members called a press conference to announce plans for a boycott of Houston’s schools. Conservative members of the organization telephoned Castillo and pleaded with him to intervene. Castillo, who had just had his eyes dilated for an optic examination, arrived to find the conference in progress, run by militant youths in khaki fatigues. Castillo himself looked like a Mexican-American version of a mafioso, wearing a dark blue suit and sunglasses to protect his eyes. But because he was older and at least wore a suit, the media focused on him. Calmly, Castillo articulated the Mexican-American community’s outrage at the way the pairing plan used their children-who were even more disadvantaged educationally than blacks-to shield more affluent Anglos from busing and integration. “If we are mixed with blacks simply to say Houston’s schools are integrated, this is not justice,” he said.

At the twenty-five paired schools and two others which had been rezoned, principals reported attendance off between 25 and 50 per cent. The school district estimated 3500 Mexican-American children stayed home during the three-week boycott, and Castillo claimed an enrollment of 2000 at the fourteen alternative schools he organized for students participating in the protest. The Huelga schools-that’s “strike” in Spanish, but Castillo translated it as “freedom” for the Anglo media- managed to attract 85 state-certified teachers. That was a tribute both to Castillo’s church and community connections, and to the depth of resentment in the Mexican-American community over the pairing system.

The court decision had been announced just five days before the beginning of the school year. Both inside and outside Houston’s barrios, community leaders had been impressed by Castillo’s skill in directing the spur-of-the-moment boycott and in setting up the panoply of tutoring and other program that survived it. Yet there was discord, too, over MAEC’s ultimate failure to convince the thin (4- 3) liberal majority on the Houston School Board to include Anglo schools in the pairing plan. The board eventually agreed to appeal the black-brown pairing to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately refused to hear the matter. After school officials agreed to increase hiring of Mexican-American teachers and administrators and promote the use of bilingual education, the MAEC called off the boycott.

Although substantively it had achieved mixed results at best, psychologically and politically the boycott was a signal achievement. And although Castillo had not seemed to seek personal recognition, he had achieved it. A relative newcomer to Houston, he had been in the right place at the right time when the Houston media were seeking a spokesman for the burgeoning Mexican-American civil rights movement. His intelligence and his carefully considered speech, his disarming friendliness and willingness to compromise, and his obvious commitment to Mexican-American causes helped catapult him to prominence. His efforts in the boycott had also, as a side effect, created an organization-a cadre of bright, capable, and hard-working Mexican-Americans. Inevitably, he began to think about his next move.

Saul Alinsky, the late radical community organizer, wanted to train an organizer from Houston who could return to “rub raw the festering sores of discontent.” Castillo met with him at an airport restaurant in Dallas to discuss the idea, but nothing came of it; their philosophies were too different. Alinsky was suspicious of politicians and felt that the proper way to deal with them was to create movements so strong that politicians couldn’t ignore or even fight them. Castillo had a different agenda: “I always thought Alinsky’s techniques actually stopped short of getting into the political process. They involve raising a lot of sand to throw in the mayor’s eye, but when it’s over, he’s still the mayor and you’re still raising sand. If you want to change power, you have to get power.”

To Castillo, the obvious way to do that was to run for office. It was the logical next step for him. Almost as soon as he arrived in Houston, he had joined and helped revive the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO), an almost moribund outgrowth of the 1960 Viva Kennedy organization. He had intended to run for city council but discovered in checking the city charter that the residency requirement for council member was five or more years; in 1971 he had lived in Houston only a little over four years.

Exploring the charter for other alternatives, Castillo could find no such residency requirement for the post of city controller. The charter’s archaic language did not make perfectly clear what the controller’s specific duties were, but it suggested that the job had pivotal-if negative-power. In fact, the controller is the city’s fiscal watchdog, chief disbursing agent, and banker of its funds. Because the controller’s signature must appear on every check issued by the city and on every contract entered into by it, he is the only official who can say no to Houston’s strong mayor and weak council. Obviously, he does so at his own peril unless he can demonstrate that the funds haven’t been lawfully appropriated or are insufficient to meet obligations. But before the city’s annual calendar-year budget is submitted by the mayor and approved by the council, the controller’s authority is magnified immeasurably. (In 1976, as sometimes in the past, half the year was gone before the budget was approved. In the absence of an approved budget, the controller theoretically could veto any expenditure. In practice, Castillo has only questioned spending which greatly exceeded a department’s budget for the prior year.)

The office had one main drawback: politically it seemed practically invisible. Few voters seemed to know the duties of the controller, although for 24 years they had elected a fellow named Roy Oakes to do the job. In fact, in all those years Oakes had never even had an opponent. Maybe that was because he looked so much like what central casting would order if it needed someone to play the part. A flinty fiscal conservative whose financial prudence was mirrored by his personal style, Oakes dispensed his change from a coin purse and sometimes even wore a green eyeshade. Mayor Louie Welch used to joke that Oakes was the only man he knew who wore both suspenders and a belt. And Oakes was as cautious with the city’s money as with his pants: he required, for example, that the bank serving as the city’s depository must pledge as collateral security U.S. Treasury bonds or notes rather than the bank time deposits or certificates of deposit accepted by some other cities. That way, Oakes reasoned, at least the whole federal government and not just a single bank would have to go under before the city lost its money.

Early in 1971, Oakes suffered a stroke that partly paralyzed him, impaired his ability to speak, and kept him away from his desk. It was widely expected that he would retire at the end of his term in December. Nonetheless, despite his disability and his age-he was then 71-Welch induced him to go for the job one last time in the November election. Welch was worried about his own campaign- he faced a tough challenge from millionaire political novice Fred Hofheinz-and he didn’t want any chinks in the establishment’s solid front.

Once again a piece of luck involving the media aided Castillo’s political career. Leonel and a funeral home accountant named H. Lloyd Jennings announced for the office, both of them praising Oakes while lamenting the state of his health. Oakes was shaken by repeated reference in the news to the fact that he had been out of his office for ten months and began making pilgrimages there for an hour or two each day. On one of these occasions a television crew came in to film him at his desk. Although no formal interview was planned, the reporter accompanying the crew approached Oakes and asked him his age. In a pitiful scene witnessed on the evening news by thousands of voters, Oakes tried but was unable to answer. Oakes and Jennings split the conservative vote, taking 59,340 and 44,743 respectively. Castillo led the field with 67,754. Before the runoff, Jennings announced he was throwing his support to Oakes, but the gesture made little difference. Neither did Welch’s extraordinary step of dispatching City Treasurer Henry Kriegel to warn that “to turn over more than $200 million in city funds a year to a completely inexperienced man might well result in the city’s losing its high credit rating and strong financial position.”

In the end, the voters seemed to say that they preferred a healthy man who had no special background for the controller’s job to a sick one who had the background but could not work. In the December runoff in which Welch defeated Hofheinz by about 141,000 to 126,000, Castillo beat Oakes 143,000 to 104,000. Welch and Hofheinz had spent a total of more than $1 million on their campaigns. Castillo and Oakes spent less than $9000 apiece. Oakes died the following September.

Castillo won his first race by building on the organization he set up for the MAEC. State Representative Ben Reyes, who quit his family business to work for Castillo in the boycott, recalls, “The council was set up as a tool for organizing. He had three people from each of the barrios-Denver Harbor, Second Ward, Magnolia, Sixth Ward, South Houston, El Dorado, the North Side-as contacts and core workers. He did the very same thing all over the city when he ran for controller.” He needed it, too, because Castillo has little of the personal appeal of such disparate Mexican- American politicians as fiery Zavala County Judge Jose Angel Gutierrez or moderate State Senator Tati Santiesteban of El Paso. Just as he did back at Kirwin High, Castillo comes across as a little studious and slightly withdrawn, a man whose commitments are intellectual rather than emotional. Democratic National Committeewoman and liberal warhorse Billie Carr, herself one of the best political organizers in Houston, interprets Castillo’s victories as proof that systematic politics can overcome lack of charisma. “He may be a little low-key,” Carr says, “but he has great organizational ability. He’s one of very few candidates l know who really understands the nitty-gritty of precinct politics and likes it.”

When he finally took office in January1972, Castillo moved slowly and prudently and seemed to try to allay fears that Welch’s scare campaign against him had inspired.

“He was aware of political realities and didn’t bust in and throw people around, and that’s to his credit,” says City Treasurer Kriegel, who has remained as Hofheinz’s main budget adviser after Welch left as mayor to become president of the Houston Chamber of Commerce in 1974. “On financial matters, he pretty much defers to our recommendations,” Kriegel continues, speaking of himself and Roland Brunet, who serves Castillo (as he did Oakes) as assistant controller. Kriegel says Castillo has done a “better job than I expected” as an administrator. “Most of his staff likes him, and that’s usually a pretty good indication.”

During the two-year term Castillo shared with Welch, he functioned mostly as a gadfly and irritant to the business-as-usual school of city administration. He criticized the annexation of water districts that permitted developers to reap windfall profits when the city acquired the districts’ bonded debt. He announced that the River Oaks Country Club’s prime 182.6 acre was on the tax rolls at $5000 an acre, compared with a valuation of $12,500 per acre for the much less prestigious 116 acres of the Golfcrest Country Club. He pointed out other flagrant discrepancies in commercial valuations and called for a complete tax equalization study; he discovered seven special city bank accounts that had not been bearing interest and estimated that they had cost the city $2 million in potential interest over ten years. He took special pleasure in publicly tweaking Welch when the mayor, who had earlier criticized Castillo’s “partisan” endorsement of Sissy Farenthold in her first race against Dolph Briscoe, endorsed Richard Nixon for reelection in 1972.

Under Welch, Castillo used the office as a forum, a bully pulpit to raise questions and take positions, such as his argument that the city should end the privileged status of the Ship Channel Industrial District. Under a ten-year deal with the city, industries along the Ship Channel pay no taxes on new construction for the first five years and a sliding sum ‘in lieu of taxes” for the second five years- and pay nothing at all on their inventories. Castillo said that the city should annex the district “to raise taxes and reduce pollution.”

But he had no power to be anything more than a thorn in Welch’s side, and Welch often accused him of going off half-cocked. Castillo lost a fight with Welch over what role the controller should have in estimating the city’ revenue when Welch successfully usurped the whole function. At one point, Castillo threatened to veto Welch’s 1973 budget unless Welch lopped $10 million from the $234.4 million total. That was something he could have done, but he failed to make good on the threat-a sign of prudence or weakness, depending on your perspective.

He did continue sniping at the mayor, charging that Welch inflated his revenue estimates and was sandbagging the man who would follow him. “He’s just trying to push off a tax increase on the next mayor,” Castillo told Houston Chronicle city hall reporter Bob Tutt. (Sure enough, Hofheinz announced in his 1974 inaugural address that he would have to raise taxes.) But Castillo was sniping with a shotgun, and there were inevitable misses, such as his advocacy of a four-day (but still 40-hour) work week for city employees. Welch won that round by producing an old city ordinance that set the week at five days. That episode remains a prime example of Welch’s favorite charge, that “Castillo has a tendency to go off on tangents.” Welch feels that politically Castillo never laid a glove on him—or at least never landed a solid punch. “We just ignored all those things as if he never said them,” Welch insists. “It really irritated him.”

Castillo’s campaign for a second two-year term was a cakewalk. While Welch stepped down and Hofheinz slipped past former city councilman Dick Gottlieb by a hair, Castillo trounced a black accountant, who had been an unsuccessful Republican candidate for state representative, by getting 79 per cent of the vote. After his reelection Castillo took one last shot at Welch, complaining that a police academy cadet class of 55 white males violated the spirit of the federal laws banning discrimination. He did not threaten to hold up the money, but he did say he would not approve any funds for future ”lily white” classes. It was a safe enough threat, for the next class would be held under a Hofheinz administration, and a mayor elected with solid support of Houston blacks was unlikely to countenance another all-white cadet class.

Castillo’s conflicts with the mayor’s office stopped almost as soon as Welch retired. He occasionally has played the gadfly under Hofheinz, particularly when he advocated, at some political risk, collective bargaining for firemen and even taped TV spots for them to use prior to the city referendum. Hofheinz ducked the issue entirely, and wisely so, since the referendum failed miserably. Castillo abo reiterated his suggestion that the city annex the Ship Channel area when the present ten-year agreement expires in September 1976. Hofheinz was silent on that one, too. A number of Castillo’s pronouncements have been remarkable for their lack of controversialness-advocating that the city purchase small cars to conserve fuel (Castillo himself actually drove an electric car for a while), or that police and firemen be offered incentive pay to take an annual agility test. (Both ideas fell on deaf ears, however.)

But mostly, during Hofheinz’s administration, Castillo has seemed to lie low. Billie Carr attributes his low profile to the fact that “he’s a team player and wants to do what’s best for the overall picture,” but others think Castillo is simply bored and ready to move on. In the closing days of his 1976 campaign Castillo showed up at an academic conference on shrinking resources at the Woodlands community about 40 miles north of Houston. Not many politicians let their long-range involvements get the upper hand over their immediate survival in the waning days of an election. The day after his reelection Castillo was quoted in the newspapers as saying his next race might be for railroad commissioner. He would like to run for mayor, but he wouldn’t oppose Hofheinz, and there is word around that Hofheinz is committed to support black former State District Judge Andrew Jefferson as his successor. Houston lawyer David Lopez, a Castillo adviser and a former member of the Houston School Board, thinks the mayor’s race would be a mistake. “He would have to raise a fantastic amount of money, and I don’t know whether he can do that,” Lopez says. Other possibilities include running for county judge against incumbent Republican John Lindsey when his term expires in 1978 or running for state treasurer or comptroller if either Jesse James or Bob Bullock steps aside. But Castillo could hardly be unaware that another Mexican-American politician from Houston-an earnest but unspectacular state representative named Lauro Cruz- was a candidate for treasurer in the 1972 Democratic primary, but ran far down in the pack with only 13 per cent of the vote.

So the problem is the old one of name recognition, and that’s the number one reason Castillo has his eye on a second challenge for chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee (SDEC). In the fall of 1974, Castillo’s decision to run against Calvin Guest came at the last minute, after Bob Bullock dropped out as the stalking horse for the liberal wing of the party. It was an uncharacteristic decision for Castillo, who, unlike some Texas liberals, is not a devotee of futile gestures and hopeless causes. “Leonel’s favorite comeback is, ‘I need a head count,'” complains former State Senator Joe Bernal of San Antonio, who is still a little piqued at Castillo for refusing to use pressure to deliver uncommitted Mexican-American delegates to Jimmy Carter last May. Lopez describes Castillo as “very careful, very good at looking at political realities, gauging them, and acting accordingly.” And former Castillo aide George Hernandez, now a member of Hofheinz’s staff, says, “He always leaves his options open. He’s forever asking questions like, ‘What do you think the odds are?’ “

Yet Castillo put together the campaign for chairman in two weeks. There were predictable react ion from delegate who asked questions like, “Can he speak English?” and tore up his card when Hernandez handed it to them, but there was some unexpected opposition as well. Although he had constantly supported labor—including the very unpopular stand in Houston of supporting collective bargaining for public employees−labor voted against him. “It crushed him,” says Eric Nelson, former attorney for a minority Teamsters local in Houston and a longtime ally. After some of the bitterness had subsided, Castillo wrote to Harry Hubbard, president of the Texas AFL-CIO. “It hurt me that you and some other labor leaders felt you had to support the side that included some persons who . . . displayed more hostility toward me and my supporters than I thought still existed in Texas,” the letter said. “Basic principles cannot be violated for short term political expediency. . . Admittedly, politics includes the art of picking winners; when I announced, I was a long shot. But hopefully in future races political philosophy will also be taken into consideration.” Hubbard’s letter in reply stressed that he had made clear all along that he was sticking with Briscoe and “party unity.” In response to racist incidents Castillo enumerated—delegates calling him a spic, telling him to go back to Mexico, refusing to shake his extended hand, and booing him before he spoke—Hubbard said he had nothing to do with them and expressed little sympathy: “I understand during heated campaigns things are said and done which would have been better not said or done. However, those things are not new to me or you.” Castillo ended up with about 42 per cent of the vote.

Having come so close last time, Castillo would seem well positioned to win the state party chairmanship this September after the June State Convention demonstrated how weak the conservative party leadership is. But it isn’t that simple. Late this spring Castillo was running afoul of an increasingly intense rivalry between blacks and browns, a destructive competition cleverly exploited by the conservatives in control of the party machinery. In a gesture consistent with his history and with reality as well, Castillo pledged not to run for state party chairman without the endorsement of the black caucus. But the caucus already cut a deal with the party leadership to have a black elected vice chairman in September and was worried that Castillo’s election might upset that deal. Some black leaders argued that neither Castillo nor any other Mexican-American deserved the state party chairmanship because browns, although more numerous than blacks in Texas, vote less faithfully and less solidly than the black bloc. There were also complaints that Castillo had not consulted enough with blacks over the past two years and had not put enough of them in jobs in the controller’ office. Typical of this view is State Representative Craig Washington of Houston, who nominated Castillo for state party chairman in 1974. Now Washington charges that Castillo has been virtually ignoring blacks, although “we elected him.” The onus is on Castillo, Washington says, to prove to blacks that he isn’t like those Anglo politicians “who only come around every two years looking for votes.”

As his next challenge for leadership of the SDEC nears, Castillo is looking less and less like a community organizer made good, and more and more like a fiscally responsible politician and administrator with statewide ambitions. The controller’s staff is undertaking an “energy audit” of power usage by city departments and facilities, an idea possibly inspired by his visit to the Woodland conference. He has held up a $632,000 expenditure sought by the police department to fund its third cadet class of the year because the department by early June was already $5 million, or 26 per cent, over last year’s expenditures and the city council still hadn’t adopted a budget for this year. Like conservative Texas politicians, Castillo isn’t above drawing comparisons between

Houston and financially troubled New York City. Justifying his denial of the police department’s request, he said, ”Maybe if Abe Beame had done something like this when he was New York’s controller, New York might not be in the shape it is today.” And Castillo talks now about the need for a Hispanic Chamber of Commerce in Houston and the value of Junior Achievement and similar business-oriented programs for Mexican-American youths.

Not long ago Castillo moved his family in to a large four-bedroom house with a swimming pool and a spacious lawn on South MacGregor, a neighborhood that once was home to some of Houston’s most prominent Jewish families like the Weingartens and the Sakowitzes but is now overwhelmingly black. Castillo explains that he and his wife sold their former house for $29,000 and used the entire sum as a down payment on a new one, and they meet the payment from their joint annual income of about $24,000 (she runs a small real estate business and he teaches evenings at the University of Houston graduate school of social work). Still, the fact that he sends his children to parochial schools and lives in a $72,000 home has not gone unnoticed, either inside the Mexican-American community or outside it.

So far, however, Castillo has retained the strong loyalty of virtually all factions in the traditionally divisive and byzantine world of Mexican-American politics. His relaxed personal style has deflected the hypercritical envy Mexican-Americans have often shown to their fellows who get ahead politically. Castillo has also managed to assuage both radicals and conservatives, starting with the boycott, when an appearance by angry young Chicanos before the Houston School Board erupted into a fist-swinging melee (you can still get an argument on whether police, school security men, or the youths threw the first punch). Castillo publicly deplored the incident— but he personally bailed the kids out of jail. Carlos Calbillo, one of those arrested at the school board meeting, says now, “Leonel has an understanding of Chicanos as a colonized people, but he has also made some of us appreciate that in Houston we are a minority. The fact is, he’s made progress and the others who were preaching hate have not.”

How much progress? Because of his efforts, there are a few more Mexican-American politicians in public offices—precinct judges, constables, his ally and protegé, State Representative Ben Reyes. Undoubtedly Castillo’s supreme technical skill at the business of politics has helped raise Mexican-American consciousness about, and involvement in, electoral politics. But despite what pluralist arguments say, politics is not just a matter of participation. It is the business, as political scientist Harold Laswell has written, of who gets what, when, and how. For many Mexican-Americans, especially those who do not speak English, he serves a function not unlike that performed by Irish or Italian ward heelers in the Northeast around the turn of the century: he serves as their ombudsman and interpreter in dealing with city government, shepherding them through the often complex and confusing processes entailed in routine matters like getting a disputed water bill adjudicated or having a dangerous nuisance like a dead tree removed from a city right-of-way. Ward heeling is hardly a traditional activity for a controller, but his role of advocate and friend-in-the-system for 12 per cent of the city’s population was inevitably thrust upon him as Houston’s most visible Mexican-American. (Castillo’s staff estimates that at least a third of his callers, sometimes as many as three-fourths, speak only Spanish.) Not surprisingly, Castillo’s role as ombudsman irritates other city officials far more than his occasional criticisms or policy pronouncements. City Treasurer Kriegel complains that Castillo “spends a lot of time and effort seeing what he can do to help the minority community,” an attitude shared by much of the old-line bureaucracy which stayed over after Welch. All politicians, Anglo or Mexican-American or whatever, use their offices to keep their fences mended and to shower benefits on their political base. Castillo does it; so did Louie Welch. The only difference is that Castillo’s Mexican-American constituency is much more readily identifiable than Welch’s cronies in real estate and business.

Exactly how much Castillo has done for Mexican-Americans as a group, rather than individually, is a matter of conjecture. The flow of federal money into Houston has mushroomed from $11 million to $60 million since Castillo’s election, and although he has no power to initiate requests for federal funds, if he were disposed against them (as his predecessor Oakes was), he could stop them cold. When he has found abuses, as he did in programs to aid Mexican-American and black contractor, he overruled the city council and shut the programs down entirely. But he has clearly not become what the Houston establishment feared, and some radicals hoped he might: a Mexican-American Huey P. Long who would try to take over the city on behalf of its poorer class.

Radical Rice University sociologist Chandler Davidson, in his 1971 book Biracial Politics, argued that a political coalition to accomplish such a takeover in Houston could be formed from minorities, trade unionists, and religious groups. By training, Castillo would be better suited than any other Houston politician to forge such an alliance. But although he calls himself a “populist progressive” and shows up at conferences around the country where New Left politics are bandied about, Castillo has made no effort to be a Kingfish, nor has he trafficked much in the political goods other politicians traditionally have dealt to their constituencies—jobs, contracts, services.

Instead, he has put his energy and intelligence into projects like devising a municipal variant of Louis Kelso’s Employee Stock Ownership Plan, a proposal to “save” capitalism by putting some stock in the hands of the workers. Castillo’s variation would allow city employees and others of low and moderate means to buy small-denomination municipal bonds, the interest on which is tax free. He toys with ideas such as Buckminster Fuller’s mouth-filling concept called “ephemeralization”- which Castillo defines as “getting more and more from less and less.” He delights in “right-turn-on-red” types of ideas and produces a steady flow of piecemeal suggestions to ameliorate traffic congestion, create educational parks, and cut the tax burden on low- and middle- income people presently penalized by higher taxes if they improve their property. He shines at conferences such as one recently in Austin on alternative state and local politics.

Meanwhile, he seems to be soft-pedaling some of his earlier causes that might alienate a business constituency, such as his longtime advocacy of annexing the Houston Ship Channel Industrial District. He hasn’t backed off from the idea, precisely. He simply has not found time for developing the kind of data necessary to win that fight— by clearly demonstrating that the taxes gained would not be offset by the city services that would have to be provided. Similarly, he hasn’t found time to act on improving the status of city laborers—a program he had declared a priority at the end of last year. City laborers are hired, in effect, on a new contract every day. They lack the most rudimentary civil service protection and are among the lowest-paid workers—and they happen to be mostly Mexican-American and blacks. Recently Castillo went to the computer printouts and was surprised to find that there were hundreds of people in this classification. As of this writing, he hadn’t yet acted on the situation. One reason may be that to ask the city to treat these workers more equitably runs counter to “‘fiscal conservatism”: it means paying more money at a time when the political mileage is in paying less. Perhaps Castillo has come to the point at which social justice and higher political horizons for himself are incompatible. Perhaps they are for any minority politician who seeks state office.

This is a Horatio Alger story without an ending. Leonel Castillo’s promising story is still unfinished. All anyone can be sure of is that this fall he will be out on the hustings, working to bring in the Mexican-American vote for Jimmy Carter, whether he is SDEC chairman or not. If Carter is elected and is as good about appointing minorities to his administration as president as he was as governor of Georgia, maybe Leonel Castillo will become an under secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, or perhaps he will get omc other of the personal rewards that are the accepted spoils of politics. Maybe he will remain home and become Houston’s mellower answer to San Antonio’s maverick Congressman Henry B. Gonzalez. Whatever he does, he will move as he always has—slowly, carefully, a step at a time, checking his options, covering his bases, getting his head counts. One night, as he drove his 1972 Toyota from Austin back to Houston, a reporter asked him what fantasy appointment he would want if Carter were elected and were disposed to grant his wish. Castillo pondered a long time. Then he said, “I could really get into being the Ambassador to the Philippines.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy