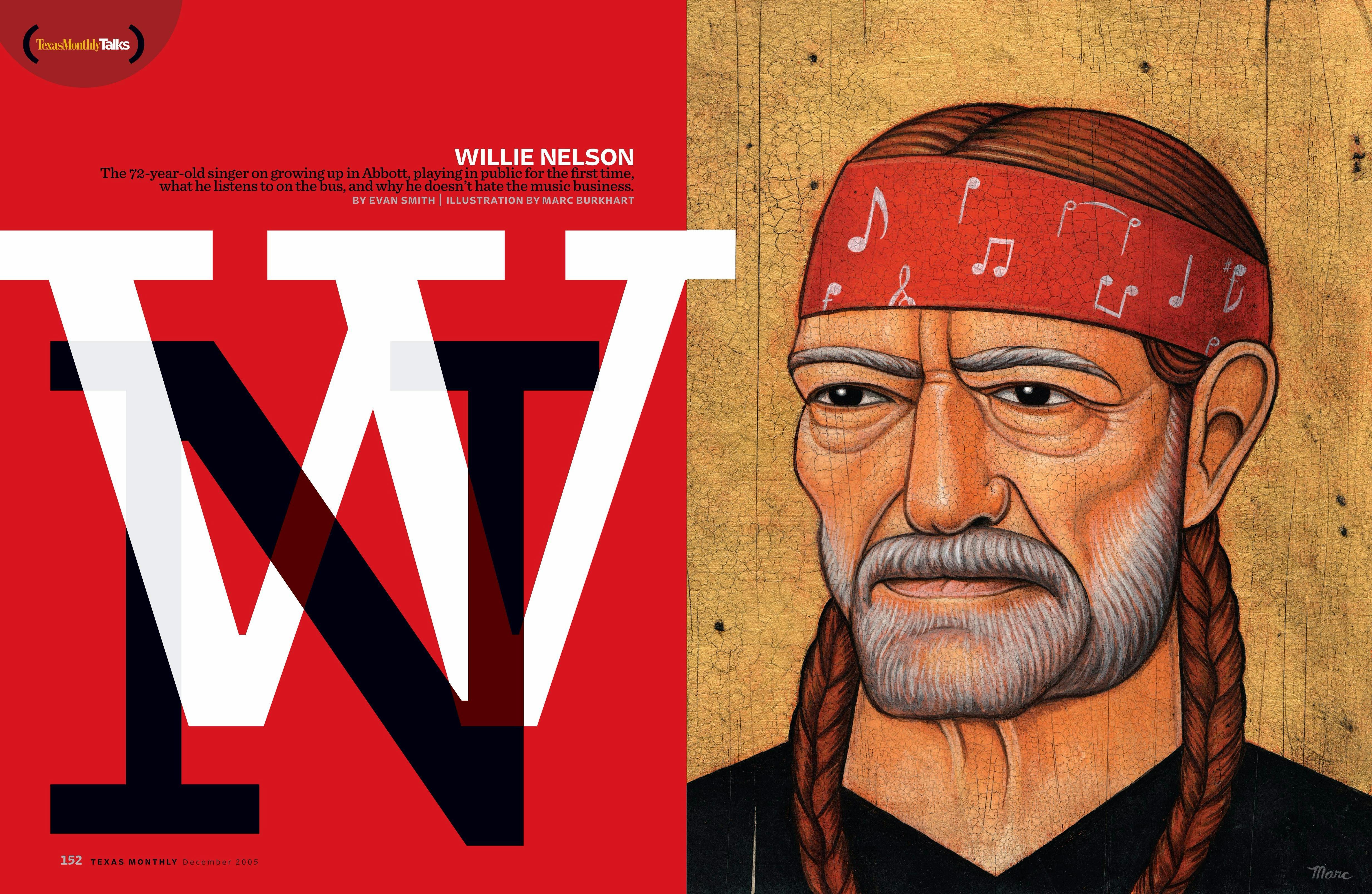

Evan Smith: Could there have been a Willie Nelson without an Abbott?

Willie Nelson: I doubt it. I’ve always felt like Abbott was a special place. It was the perfect place for me to grow up because it was a small town and because everybody knew everybody. Everybody there was friends or family or worked together or went to school together. There was something real positive about that.

ES: In a lot of small towns, everybody gossips about everybody else; there’s nothing positive about that. But not in Abbott?

WN: If it’s gossip that bothers you, you’re in trouble, because there’s gossip everywhere, in little towns and big towns. I was a telephone operator in Abbott back when they had telephone exchange operators. My sister was really the one who had the job. Whenever the operators would take a vacation, they would hire her to run the board, and I would come in and help her. All the time I was sitting there, I’d be listening in to the conversations going on all over Abbott. I tapped every phone in town! I knew everything about the whole county.

ES: What’s your earliest memory of Abbott?

WN: Playing in the mud and the creeks and the water and the cotton patches.

ES: Did you have any sense back then that there was a whole other world out there, and were you interested in seeing it?

WN: No, I didn’t think there was a lot out there for me. I was surprised when I left Abbott that there was another world out there, because I thought we had it all right here. In a way, Abbott was a little bitty picture of the whole world. You had nice people, you had assholes, and you learned to live with them and like them and work with them. I thought it was a good education growing up there.

ES: Tell me about the house your family lived in.

WN: The first one was down at the edge of town. We had a house with a well where we got our water. We had a garden we grew vegetables in. We had a hog pen where we raised hogs and cattle. We had a barn where we fattened up calves. I was with the Future Farmers of America, so every year I had a project. I loved being outside.

ES: Big house or small house?

WN: Very small house. My parents were divorced when I was six months old, so it was my sister and my grandparents who raised me. My grandfather was a blacksmith. I hung out with him every day in his shop. After he died, we moved to another house just a couple of blocks to the north, and my grandmother started teaching school and cooking in the school lunchroom. The house was a little bigger and a little nicer. It was right next to the church tabernacle, so we got religious services through the summer. We were pretty well soaked in religion.

ES: Did it take?

WN: Yeah. I realized there’s a higher power. There’s somebody smarter than I am out there, and I’m not picky about who it is. It’s like Kinky [Friedman] says: “May the God of your choice bless you.” If you’ve got one, you’re all right.

ES: You’ve been back to Abbott a bunch of times over the course of your life, right?

WN: I still go back a lot. I just bought another house there—the doctor who delivered me used to own it—and we fixed it up a little bit. That’s where I spend some time every now and then.

ES: Could there have been a Willie Nelson without a Texas?

WN: I don’t think so. Texas suits me so well. I love the freedom, the wide-open spaces. Now, a lot of people out there might say, “That’s a load of horseshit, because I live in Oklahoma, and we’re just as crowded as you are.” I’m sure that’s true.

ES: Is Texas a good place to make country music, or do you have to go to Nashville?

WN: I went to Nashville because that’s where I thought you went to sell your product. Maybe it still is. Maybe you take care of your business in Nashville because that’s where the store is—that’s where they pay you off, that’s where your publisher and your record company are. In my day, Nashville was where you needed to go to get some recognition, so I did. And then, when my house burned up there in Ridgetop, Tennessee, I thought it was a good time to go back home.

ES: Did it ever occur to you while you were in Nashville that Tennessee had become your home, or was it always just another stop along the way?

WN: Well, I have a lot of friends in Nashville and all over Tennessee, so it really was my home for a while. But I always thought I’d probably go back to Texas one day. I didn’t realize it would be sooner rather than later.

ES: Do you respect the popular strain of country music that comes out of Nashville now?

WN: I respect songwriters and musicians probably more than anybody. It’s difficult dealing with the record company. You’re supposed to be commercial today and tomorrow. That was always one word I couldn’t get along with, “commercial.” I never could fall into any of the categories that they would say were commercial.

ES: Was there ever a point in your career when you thought, “I need to get with the program and figure out a way to be more radio friendly or album friendly or I’ll never be successful”?

WN: Never. I always thought that if I was having fun doing what I was doing and making a living doing it, then I was already successful. I didn’t have any idea I’d be this successful, but the first night that I made money making music, I knew that I had succeeded.

ES: Do you remember when that first night was?

WN: I played rhythm guitar in a bohemian polka band in West, Texas. It was John Rejcek’s band. There’s no way he could’ve heard anything I did, but I would just sit there and play, make my mistakes and move on. I made $8, so I’ll never forget that.

ES: How did you get the gig?

WN: He was from around Abbott, and he was a blacksmith, like my granddaddy. We had a lot in common, I guess, and I think he just liked me. I grew up playing with his kids. He had sixteen kids, and they were all musicians. Every one of them could play horns or drums or something.

ES: Could you ever imagine having sixteen kids in your life, Willie?

WN: There probably would have been sixteen wives and one Willie.

ES: Who taught you to play the guitar the first time?

WN: My grandfather taught me some open chords and taught me to play a couple of songs. After that, I picked it up from various people, listening to the radio and hanging out with other guitar players who happened to come by.

ES: Do you remember the first song you learned?

WN: The first song I learned was “Show Me the Way to Go Home.” You ever hear that song? [Singing] “Show me the way to go home/I’m tired and I want to go to bed.” You remember a song called “Polly Wolly Doodle”? That was another one I learned.

ES: How old were you?

WN: I was six when I started playing guitar, but I started writing songs when I was about five.

ES: And your grandfather gave you your first guitar?

WN: Yeah. It was a Stella guitar, from Sears, Roebuck.

ES: When was the first time you played by yourself?

WN: I started a band when I got to high school. It was me and my sister—she was a junior then—and a guy named Bud Fletcher, who she eventually wound up marrying. I had my football coach in it; he played trombone. My dad played fiddle, and we had a guy named Whistle Watson, out of Hillsboro, to play drums. We were probably pretty bad.

ES: And the name of the band was . . .?

WN: Bud Fletcher and the Texans.

ES: Why not Willie Nelson and the Texans?

WN: I was the guitar player and the singer, but I wasn’t really old enough to go out and book the jobs. We put Bud’s name on it because he was the front man.

ES: Was there ever a time when you thought you would end up doing anything other than this to make a living?

WN: I always thought I would figure out a way to do it with music. I knew I might have to do other things along the way. Of course, I have had to do other things: I was a disc jockey, a vacuum salesman. I got a pretty good education in that respect.

ES: At what point did you no longer have to do those odd jobs to make enough money to live on?

WN: When I started playing in clubs all the time, it was harder to do a day job as well as play six nights. So it kind of eliminated itself. I drifted over into the nighttime and got away from the salesman stuff that you have to get up early in the morning to do. I couldn’t do them both for very long, so I finally gave up the salesman part.

ES: What do you like about what you do?

WN: I love to play. I love to play to an audience. I love having good musicians around me. I love the fact that we travel from one place to another. That keeps it new and fresh every day.

ES: You’re on the road an extraordinary amount of time.

WN: Almost all the time.

ES: What sort of music do you listen to on the bus?

WN: I listen to XM satellite radio a lot because I can pick it up all the way across the country. When you travel as much as I do, satellite is the most dependable thing. You hear a song and think, “Wow, that takes me back.” That’s the joy in listening to traditional music. It’s like Trisha Yearwood said in her song: “The Song Remembers When.”

ES: Since you mention traditional music, there ought to be a Willie Nelson channel on satellite radio, if there isn’t one already.

WN: Well, I do a radio show on XM channel 171 every Wednesday. They call it Willie Wednesday. I’m on with Bill Mack, my old disc jockey buddy from years and years ago. When he was in Fort Worth, he was the Midnight Cowboy, but now that he’s on XM, he’s the Satellite Cowboy. A guy named Eddie Kilroy also has a show, on channel 13. I listen to that a lot, because you can hear Lefty Frizzell and Bob Wills and all that good stuff 24/7. What happened to that kind of music? Why has it been forgotten by so many people? The bottom line is whatever’s commercial today, whatever’s selling. And, you know, Hank Williams is dead, and Bob Wills is dead, and they can’t make any more money off of them. They move on to somebody else.

ES: Do you have the bad feeling about the music business that a lot of other people have?

WN: No. You might think, “Whoever is running this record company is going to run it into the ground and ruin music” or “Whoever’s doing all these radio stations, they’re going to ruin music,” but I don’t think so. I don’t see it. I know a lot of guys who are doing it a different way. In Austin there’s Sam and Bob. They have a radio show in the morning over there on KVET, and they play great music. And they’re at a Clear Channel station! It just depends on the personalities. Some stations will play good music and some won’t.

ES: How hard must it be to play good music?

WN: There are a lot of politics going on with a lot of those records you hear played. The word “payola” has been around since I can remember. I don’t remember anybody giving me any, and I don’t remember paying anybody any, but I know it happens. Payola ain’t dead. It ain’t even sick.

ES: Does it make a difference, really, if Willie Nelson moves product anymore? Don’t they just want to have you on their label? You must get an exemption.

WN: I don’t think anyone has an exemption. I think maybe there might have been a time, years ago, when they carried you for a while even if you weren’t selling, but I don’t think that’s true today. Even with the great guys, at some point the record companies say, “That’s it for you.” They’re pretty cold-blooded; they’ll drop you in a second.

ES: I bet you’ve probably been dropped at least once in your life.

WN: Oh, I’ve been dropped and drop-kicked. But I don’t mind it. I’m just looking for a good label. I’m just looking for a fan. If I can find somebody in the executive branch who’s a fan, then I don’t really care what label it is. I can figure out a way to make it happen.

ES: Am I remembering correctly that you’re about to be 73?

WN: Born in ’33.

ES: A lot of people much younger than you would have already said to themselves, “You know something? I’ve had a good career. I want to sit in a lawn chair and drink a beer.”

WN: Well, I don’t like lawn chairs, and I don’t drink beer.

ES: So you’re not tired of this life of yours?

WN: I’ve been home [outside of Austin] now a few days, and I’ve had a lot of fun. I played some golf and rode my horse, but now I’m ready to go back out and play “Whiskey River.”

ES: How’s your golf game?

WN: I lie so much that I don’t really know.

ES: Can you get out there and beat the average person?

WN: I really don’t like to play people I can’t beat.

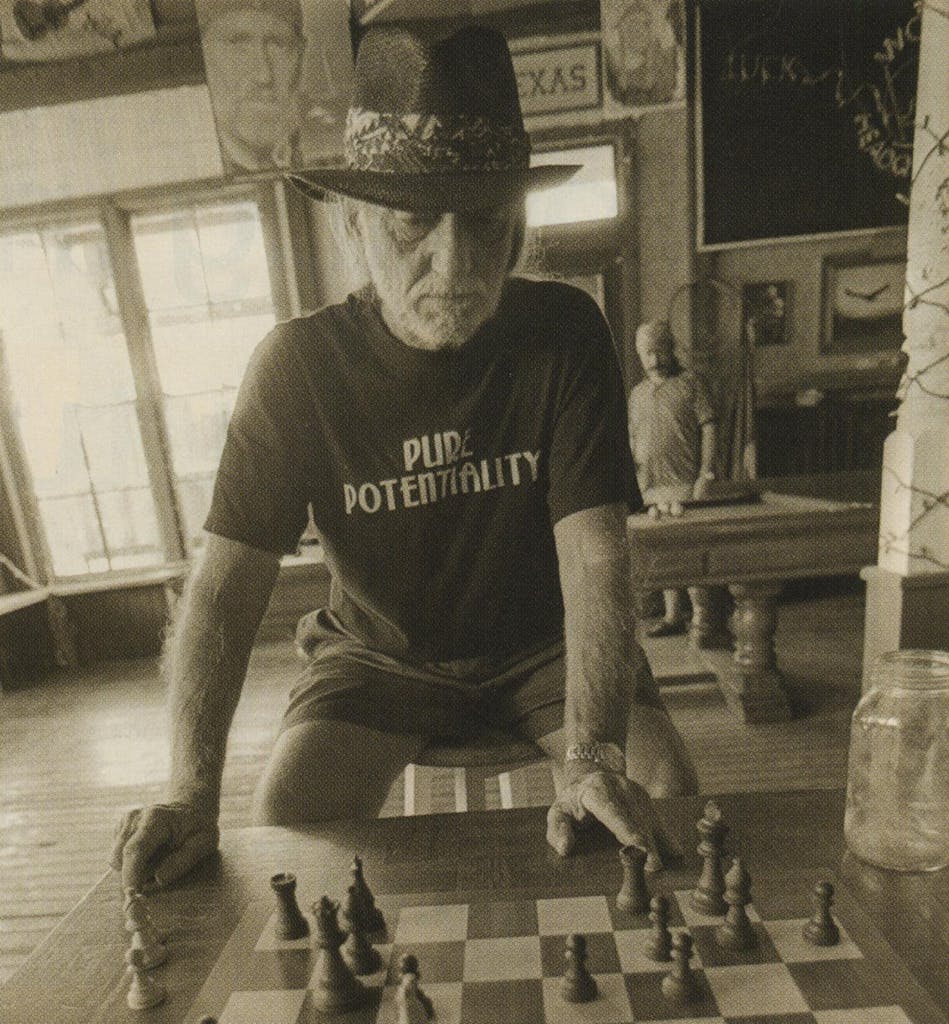

ES: Probably the same with chess.

WN: The same with chess and dominoes. I love to play all those games. I’m not a horrible golfer, but, you know, the real good golfers can have their way with me.

ES: Speaking of golf, you’re about to play in a tournament to raise money for Kinky’s campaign for governor. Are you totally on board with his running as an independent?

WN: I like what he says about himself. He says, “I might not be worth a damn, but I’m better than what you got.” I’m a farmer and a rancher, and I want to see agriculture do well. I haven’t seen any help from either Democrats or Republicans on that front. There’s plenty of blame all over the place.

ES: Kinky has made so many jokes about what your job will be in a Friedman administration that I can’t keep track of them.

WN: The last offer I had was to be head of the DEA or the Texas Rangers. I’m not sure.

ES: This is not the first time you’ve been involved in politics. You campaigned for Dennis Kucinich during the last presidential race.

WN: Right, I did back him. I didn’t have any idea if he could win, but we felt the same about the war and oil. I had to go with the guy I believed in.

ES: You don’t cut George Bush any slack because he’s from Texas?

WN: Hell no. Being from somewhere doesn’t give you any rights. I don’t have anything at all against the president personally. In fact, I understand he’s a pretty nice guy. He’s said a couple of nice things about me. I’ve got nothing derogatory to say about him, but I do think he’s getting a lot of real bad advice. The people around him who whisper in his ear all the time? They’re not his friends.

ES: So when are you going back to Abbott?

WN: I was just there a few days ago. I rode my bike around the same old roads that I used to a long time ago.

ES: I’m imagining what a kid—say, six years old or a little bit older—must think walking down the street in Abbott, and here comes Willie Nelson riding his bike. It must be a total shock.

WN: It’s not exactly like I sneak into town. The last time I was there, we had two buses parked in the driveway with the generators going. I’m sure everyone knew I was home.

- More About:

- Music

- Golf

- Willie Nelson