This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

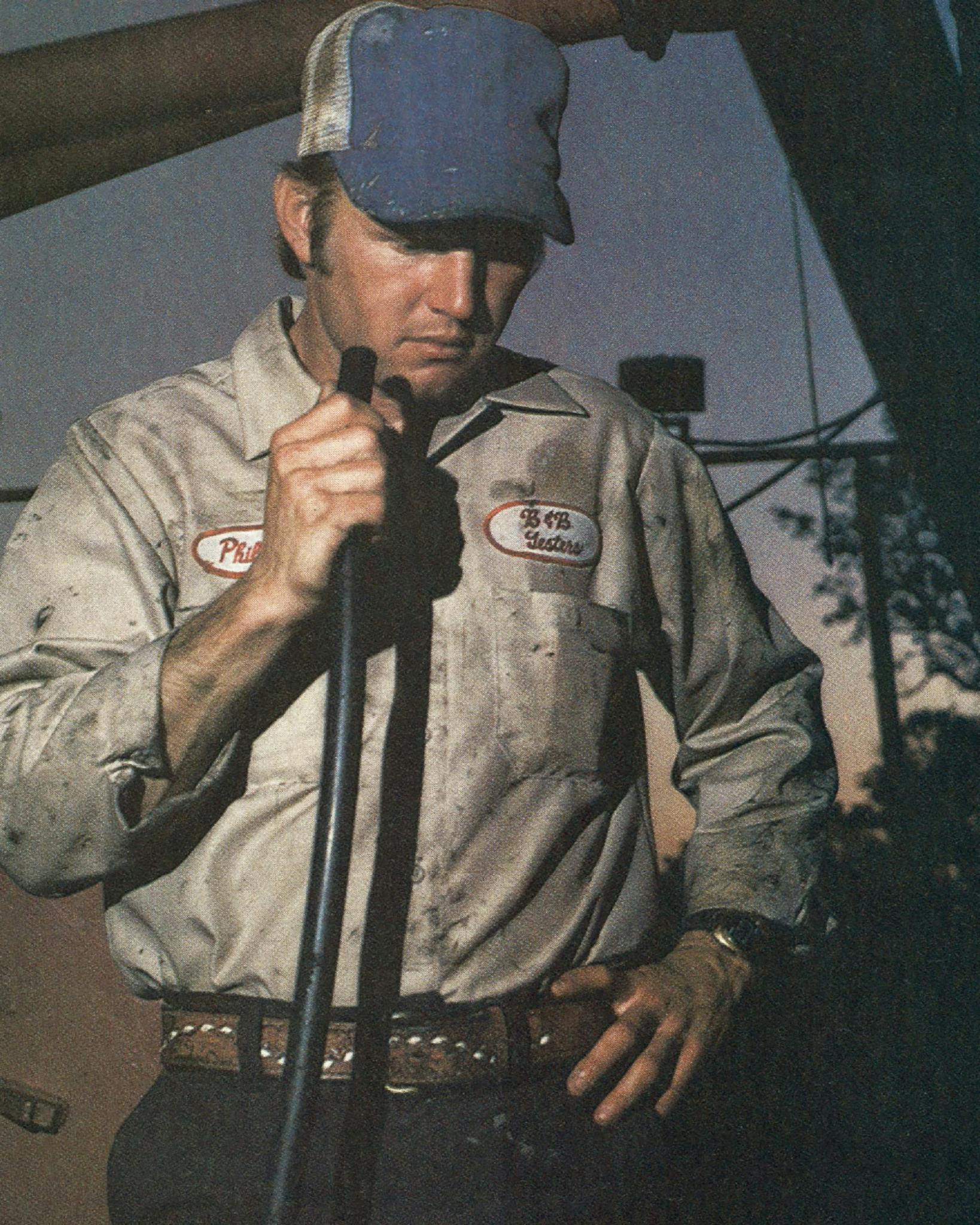

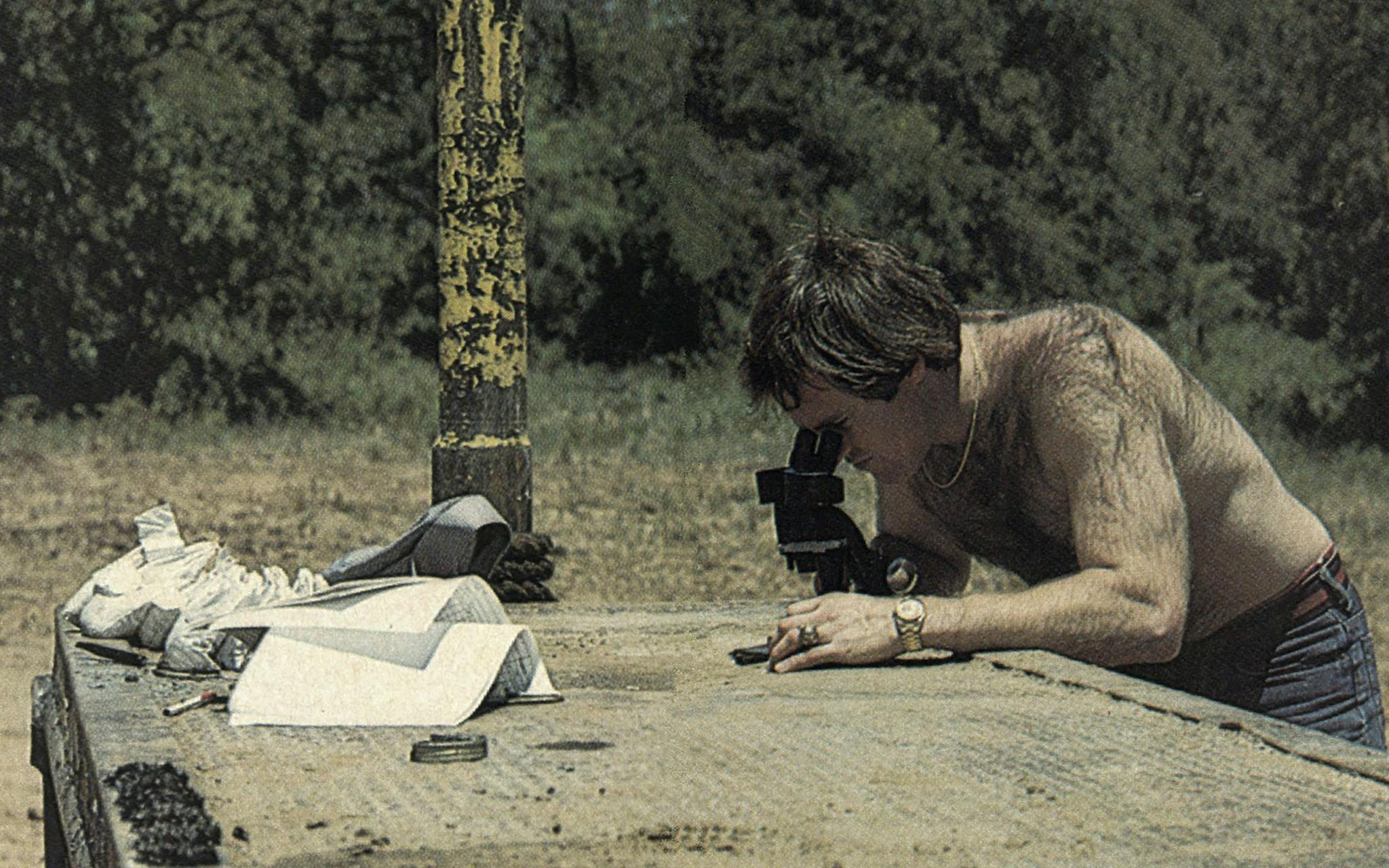

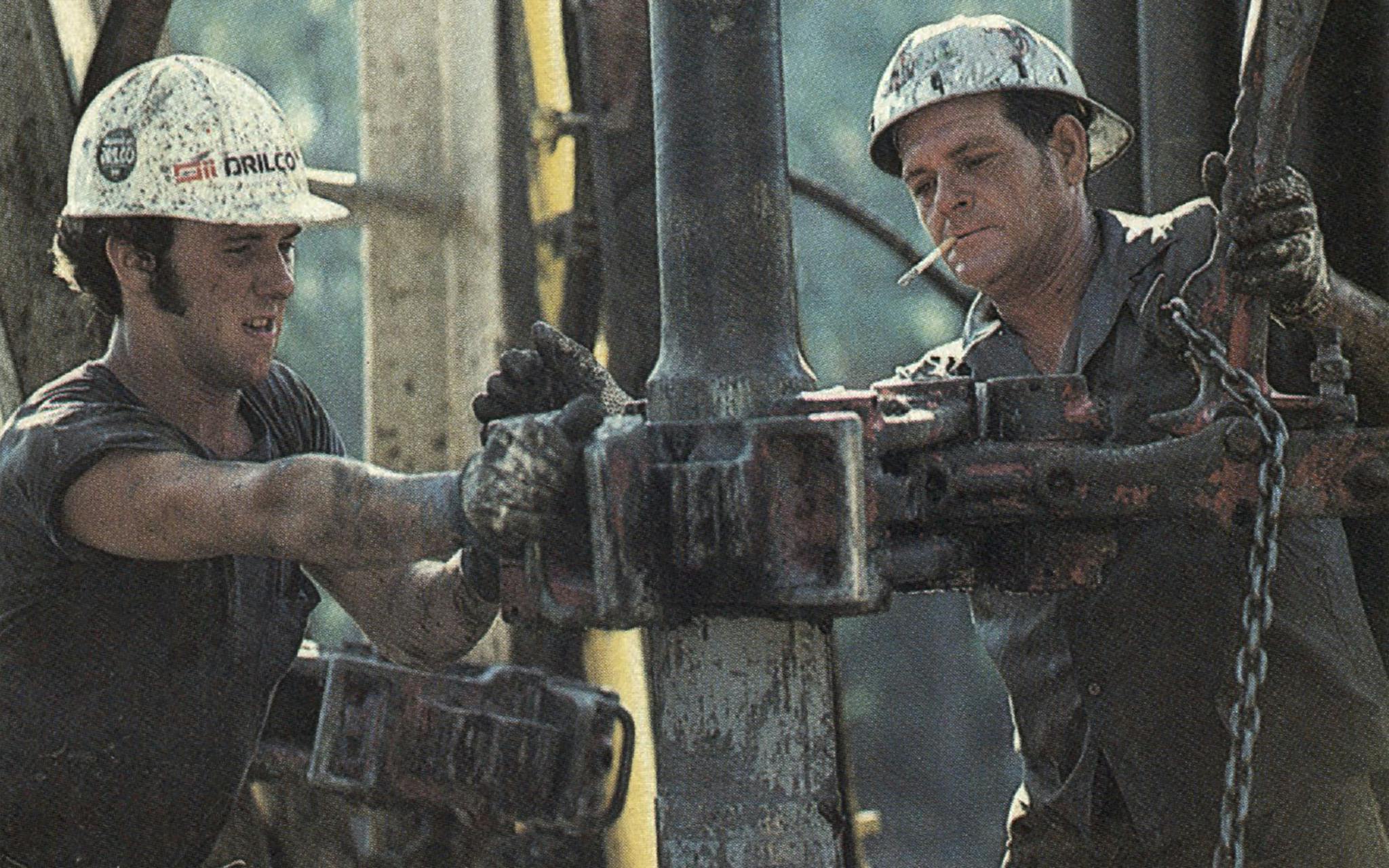

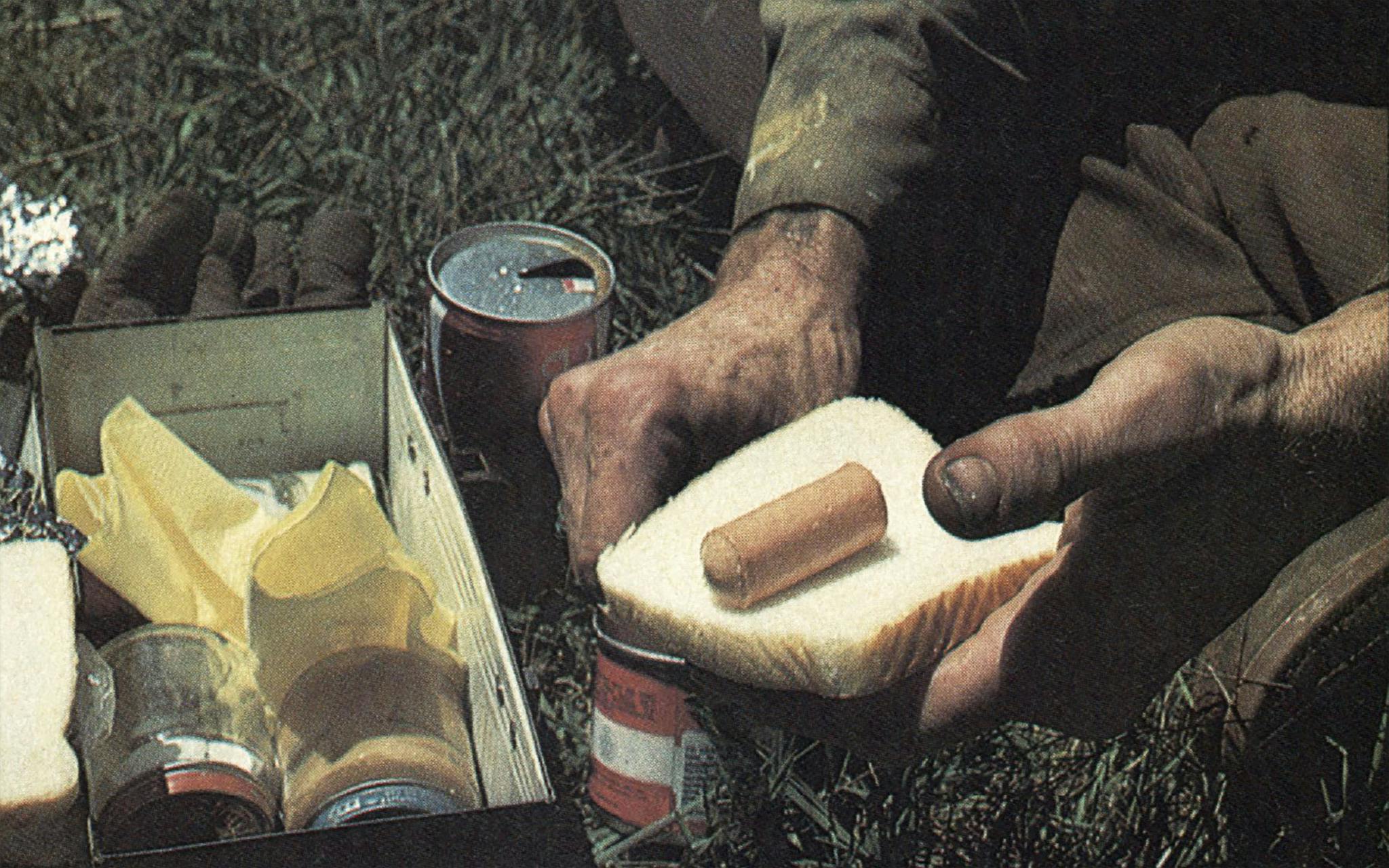

No one really likes the work. No one really likes getting out in the Texas sun and skinning his knuckles on heavy sections of steel pipe or wrestling with a spinning chain or climbing to the top of a rig where a single slip can lead to a ninety-foot fall or mixing drilling mud that gets in work clothes and combines with the grease, sweat, and oil to make a smell that no amount of washing can remove. No one likes to put up a rig in one isolated spot then take it down later only to put it up again in another isolated spot miles away. And no one likes the long hours and graveyard shifts and the endless driving back and forth to the job and coming home, as one roughneck put it, to “warmed over coffee and an asleep old lady.”

Then why do people do it? They may like the money: when there’s plenty of work, as there is today, roughnecks can make $15,000 to $25,000 in a year. They may like the people they work with. They may take pride in their toughness and satisfaction from knowing they can do a particular dirty and dangerous job better than the next man. And they may like the life that surrounds the oil rigs—the high school football games, the fishing trips in a pickup with a camper on the back, the beers on Saturday night, the long Sunday dinners after a morning in the Baptist church. But no one really likes the work.

“My dad drank an awful lot then. We literally lived in bars. I remember sitting under the table when I was just a little bitty thing, beer bottles would be flying through the air so thick you couldn’t get up. I’d reach up on top of the table and rake change off and put it in my pocket.

“They’d party all night long, then they’d get up the next morning and go to work. I don’t know how they did it. I know as a grown man now, I can’t. I could last two days and then I’d go down.”

Mickey Gaines

Roughneck

Odessa

______

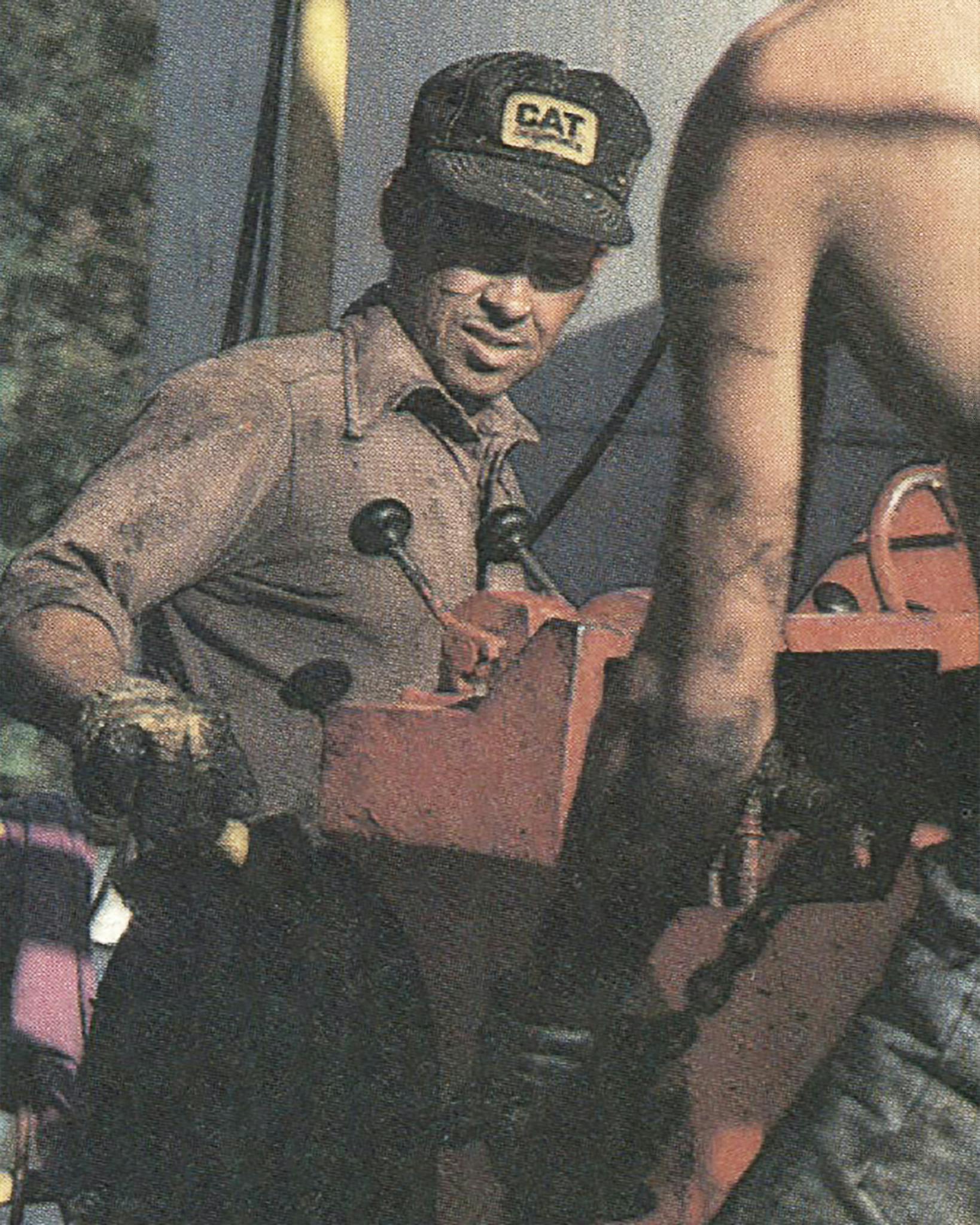

“After you spend ten to fifteen hours running pipe on a twelve-thousand-foot hole, it gets monotonous. You do the same thing over and over.

“To break the tedium the old boys that work for me goof off a little, but all the time they keep an eye on the work. Once you get bored you don’t pay attention and someone could get hurt.

“I don’t tell the crew what to do, ’cause they really know. All the crazy things they do don’t bother me.

“You start to question people—why they do things —and it breaks them apart as a crew. I don’t want to do that. I want to keep it all a sort of family-type affair.

Bob Mayer

Casing-crewman

Corpus Christi

_____________

“I was born and raised in Mississippi. I come from oil country over there. That’s how I met Tommy. I was working in a little old Dairy Queen. We met each other. I knew everybody in the oil field and helped him find work. Back then the oil field was a lot harder. If you missed a day you needn’t go back the second day ’cause you didn’t have a job.

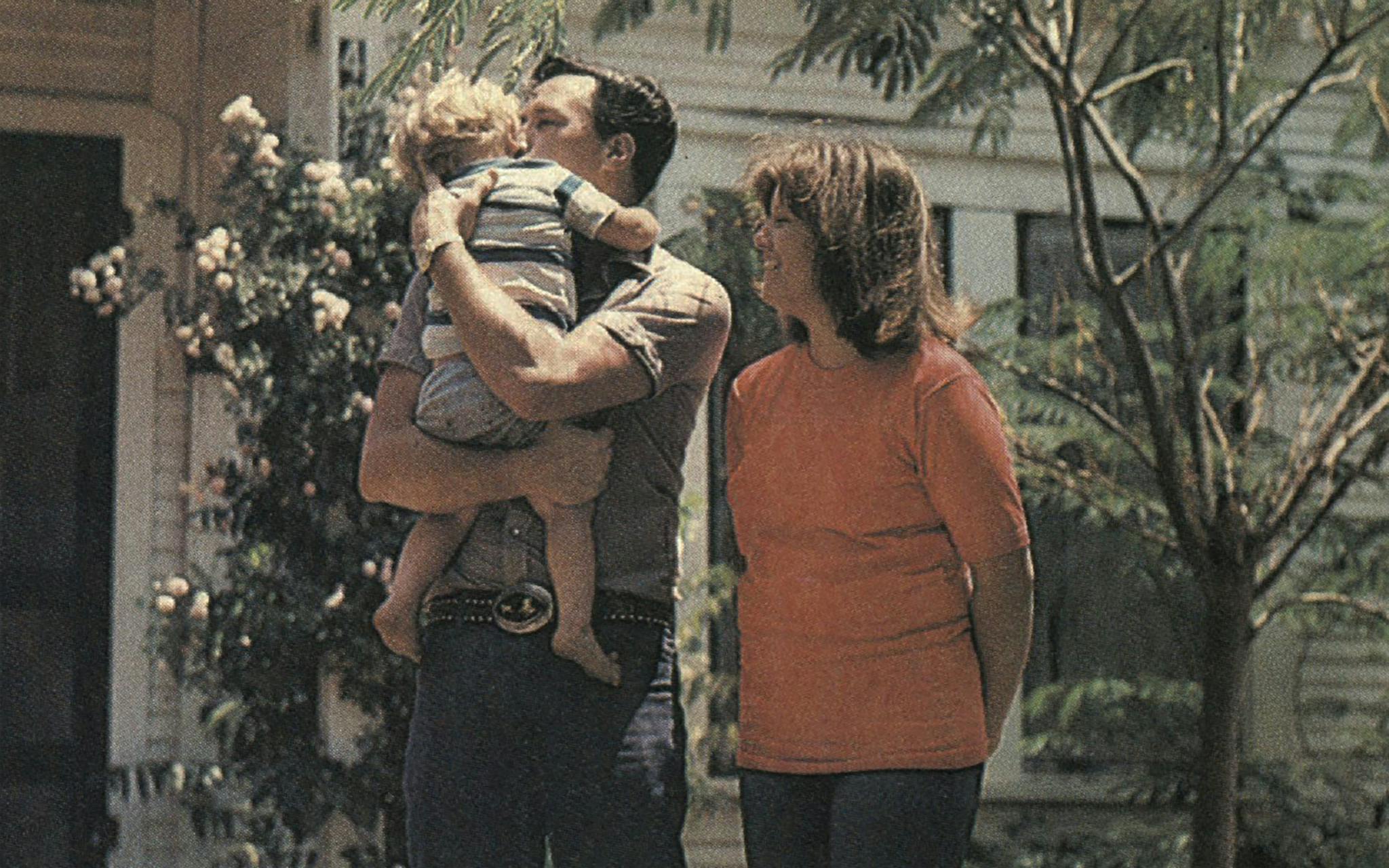

“My husband has been in the field twenty-two years now. It’s buttered my bread many a day. I love it.

“I have two sons in it. They work with their daddy. And I have another son sixteen. That’s what he’s going to do when he comes of age.

“When we go on a rig we all like to take a part in it. We like to have cookouts and invite everybody. We like it sort of like a big family. Meet a lot of people. Some good people and some ain’t worth a damn.’’

Eula Jones

Oil-field wife

Rusk

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics