Pissing off the porch seemed like the perfect metaphor for his chosen profession until one night last January, when John Graves was heading outside to relieve himself and fell down the stairs. His longtime friend Bill Wittliff had warned him this might happen. No bones were broken, but there resulted some impressive damage to his internals and his sense of dignity. After three trips to the hospital and a surgery to repair his prostate, he was still hobbling about on his cane four months later when I visited him at his home outside Glen Rose, southwest of Fort Worth, on the spread he calls Hard Scrabble.

“He’s back there, working,” said his wife, Jane, as she opened the kitchen door for me, and the way she tweaked the word “working” carried with it the question, What else would you expect? She pointed to a door at the back—or was it the front?—of the house. It’s hard to get a fix on the Graves homestead, which appears to have three or maybe four front doors and I don’t know how many porches. The house rambles topsy-turvy on so many levels and in so many directions that you’re never sure whether to step up or down. The word that springs to mind is “homemade.” Every fieldstone, wooden plank, sheet of tin, and length of pipe carries John’s fingerprints. Out back is a toolshed; an old lean-to where the pet goat Door Bell used to dwell when the Graveses’ two girls, Helen and Sally, were small; and a weathered barn where John stored bales of hay when he still raised livestock.

The house is the centerpiece of nearly four hundred acres of rough limestone cedar country that John bought in 1960 with part of the proceeds from his masterful first book, Goodbye to a River. It sits on a hillside above White Bluff Creek, which flows into the Paluxy River, which in turn empties into that stretch of the Brazos that John immortalized in the book. Though it was an instant classic and hailed the coming of a major new talent, his publisher, Alfred Knopf, despaired when he heard that John was buying this piece of land. “There goes his next book,” Knopf’s wife, Blanche, groused. Their experience had been that when a writer gets interested in a piece of land, he stops being a writer, at least for a considerable time. Her fears were well-founded. It was fourteen years before John mailed off his second book, which he called Hard Scrabble: Observations on a Patch of Land, a loving meditation on this spread of rocks, cedar, and rushing creeks. “Hardscrabble” indicates a piece of land that approaches but does not completely measure up to useless. It’s the kind of place that only a writer could love and make work. Fortunately, John, who turns ninety this month, is a born writer, one of the best our state has ever produced. “If I hadn’t wasted so much time building and chasing cows,” he confesses, “I could have written a whole lot more. But what the hell, that’s how it was.”

It has now been fifty years since John published Goodbye to a River and bought Hard Scrabble. Blanche Knopf may have been right; maybe we would have had more books had he spent the past half-century living in Fort Worth, watering the lawn and walking his dogs around the block. I doubt they would have been as good as the ones he did write, but it doesn’t matter anyway. In Hard Scrabble, John writes that the place “had me,” and I suspect that it’s always been with a strong grip. His writing life seems to be an organic extension of this hostile soil, and his attempts to put his feelings for it into prose form a type of love song. Whether he shaped it or it shaped him is a matter of no great concern.

I’ve known John Graves for thirty-something years but hadn’t seen him in some time. He’d been on my mind, though. Whenever the trivial pulse of contemporary life gets to be too much for me, I tend to think of John, who measures contentment in direct proportion to the time it takes him to reach an interstate or a shopping center. His deep streak of contrariness rejects that which obsesses most people, the grasping at fame, fortune, and a view of the eighteenth fairway, and for some time, I’d been feeling a strong pull in his direction. As I traveled the back roads to Hard Scrabble, leaving that buzzing world behind me mile by mile, I realized that just breathing this air was a rejuvenating sensation I’d been in danger of losing.

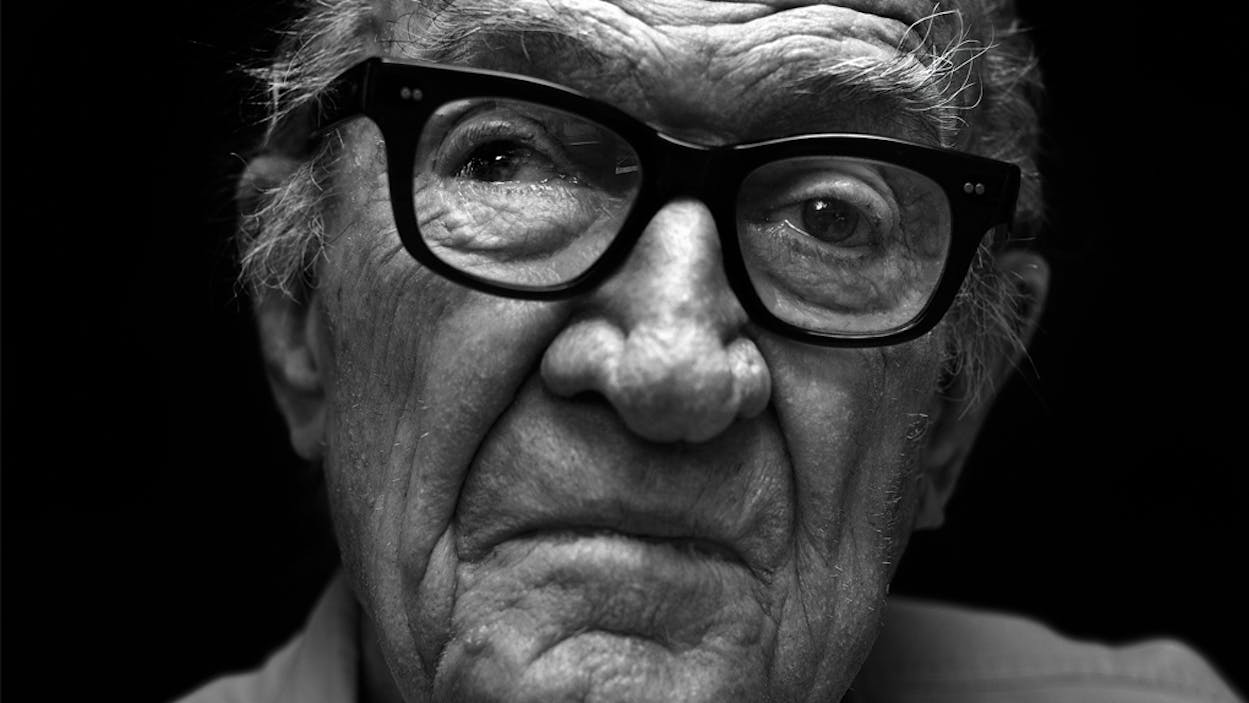

I was mildly alarmed, therefore, to find John looking so frail. He was thin and bent, fragile as a leaf. His trademark horn-rim glasses kept sliding down his nose, but that familiar twinkle of mischief was still backlighting his right eye—the left one has been glassy blank as long as I’ve known him, victim of a Japanese grenade on the island of Saipan in World War II. Tiny pieces of metal remain buried over his right eye, under one knee, and in his back.

“I’m still here,” he said cheerfully, inviting me into his present-day office, a large room in the oldest part of the house. The walls are covered with shelves of books on every subject you’re likely to think of. Propped on the mantel of a huge fireplace is an old photograph of John fishing for tarpon in the Florida Keys. John told me he no longer uses the fireplace for fear of disturbing a family of swifts that nests in its chimney when the weather is warm. The outside door—he still calls it “the front door”—leads to the porch where he fell while peeing. John is working on a new book about “defunct friends and World War II,” working not on the old upright typewriter that was retired some time ago to Wittliff’s Southwestern Writers Collection at Texas State University, in San Marcos, but on an incongruously sleek new Apple computer. Most of his papers and memorabilia are now in the collection, including the paddle he used for his trip down the Brazos, which Wittliff rescued from a pile of kindling behind John’s house. “A cow had stepped on it and broken it in half,” Wittliff laughed, “so John just threw it away.” Rearranging the stack of pages of his newest manuscript, John sighed.

“You don’t worry much about publishing anymore, do you?” I asked him.

“No, I don’t.”

“Writing is its own excuse?”

He nodded. “These things will just end up down in San Marcos. Quite a few of them won’t be read until after I die.”

For the better part of an afternoon and again the following morning we talked about history, nature, rivers, hunting, fishing, camping, birds, Texas, Spain, Mexico, Hemingway, Thoreau, Emerson, books, writing, and, occasionally, growing old. It was a cool day, and John wore a padded vest over his plaid shirt, khaki-colored trousers, and boat shoes. Hair that long ago went white had thinned considerably. He seemed alert as ever, but his memory sometimes short-circuited, and he’d stop in the middle of a sentence and say, “What was I talking about?” Sometimes, when I’d ask a long, complex question, he would think about it for a time, then say, “I wrote about that in . . .” He’d find a book, turn to the appropriate passage, and read aloud by way of response. And why not? He’d worked hard to get that thought down in those exact words.

John is a writer’s writer, a craftsman who worries and frets over each sentence until the composition falls magically into place, a process he can’t fully explain but trusts to be there when called upon. His books manage to combine folklore, history, and nature as adroitly as the honored old guard—Dobie, Webb, and Bedichek—and do it with considerably more literary flair than any of them. Every successful writer I know went to school on John Graves. Bill Broyles, the founding editor of TEXAS MONTHLY (for whom John used to write a column) has observed that the reason John is so important is because he “takes language, which we waste out in torrents . . . and distills it into honesty.” Novelist and naturalist Rick Bass has written that John’s work “is a conduit between us and our ancient attachment to the land.”

From a middle-class Fort Worth upbringing, John grew up reading Conrad and Scott, books on Texas lore, as well as a staggering variety of arcane subjects—how to make buckskin out of rabbit hides, how to brew tea out of sumac, anything to do with the land and the people who worked it. When I asked how he knew how to build a house, he told me, “I didn’t. I got it from books.” After graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Rice University, he went away to fight with the Marines in the South Pacific. He never wrote much about war, he told me, “because so many people had far more adventurous experiences than I did.” Nevertheless, he kept track of the “band of brothers” who served with him until the last of them died. Later, he got his master’s from Columbia and taught freshman English at the University of Texas and writing seminars at Texas Christian University (one of which was attended by a young Dave Hickey). “I knew pretty quick I would never be happy teaching,” he told me. “Writing is something I’ve always had to do. I learned that when I let it take hold of me, it would somehow get up on its tiptoes and take me where I was going.”

War changed things for John, as it did for millions of others. “I came to think of myself as a sort of citizen of the world,” he once wrote, “and I felt a certain satisfaction in having never been known as ‘Tex’ anywhere except in one New York bar near Gramercy Park, where the astute owner detected my twang.” Like many writers of his generation, John was fascinated and heavily influenced by Hemingway. In the fifties, he set out for Spain to do all the things Hemingway did, fly-fish in the Pyrenees, watch bullfights, drink red wine with expatriates, write and publish. He wrote for slick magazines but also for himself, “one for them, one for me.” Once, at a bar in Pamplona, he saw Hemingway, larger than life, demonstrating how to cape a bull. He saw the great man a second time at Harry’s Bar in Venice. Both times John resisted the opportunity to introduce himself. “I thought about it,” he said. “But I hadn’t done any decent writing yet.” Besides, though he admired Hemingway’s writing, he didn’t especially care for the man himself. John told me that among his favorite writers was the Spanish poet and philosopher Juan Ramón Jiménez and quoted a line from Jiménez that expressed his own sentiments: “Foot in one’s accidental or elected homeland; heart, head in the world’s air.”

When he came back from Europe, in 1955, he had no intention of returning to Texas, except occasionally to visit family or friends. Instead, he rode the world’s air to Sag Harbor, on Long Island. He completed the novel he had been working on, “A Speckled Horse,” but his agent hated the book and eventually John gave up on it. “I probably could have got it published,” he told me. “But I decided it wasn’t good enough. I think I wasn’t suited for long fiction.” An excerpt from the book was published a few years ago, which prompted critic Don Graham to write in this magazine that “the prose sometimes sounds like an entry in ‘the bad Hemingway contest.’” I asked John if he had read Graham’s critique, and from the rumbling of his response I could tell that he had and was still pissed about it. “He was correct about the value of the book,” he admitted after a time. “But he didn’t have to be such an asshole about it.” The novel, however, taught him much about writing: “Everything you read goes into you,” he explained. “The style goes into you too, and then when it comes back out again, in your own writing, it’s yours. That has been going on since the Greeks and Romans.”

He was still struggling with the novel when he returned to Texas in 1956 to take care of his daddy, who was dying from cancer. What started as a short trip home turned out to be a lifetime, inadvertently redirecting his career. When I asked him about it, he thought for a moment, then said, “I wrote about that in . . .” He went to the shelf and pulled down a recent book by the Texas landscape photographer Wyman Meinzer. John had written an introduction concerning his relationship with the state. He looked it over and then handed it to me to read: “My writing up to that point in life, though it had supported me during my geographic ramblings, had not been distinctive except in a few short stories and an essay or two. I was well aware of this, especially after my faulty novel, and I was still hoping to find my own writing voice somehow. And ironically, where this particular ‘citizen of the world’ did at last work out his voice, whatever its merits, was right back where he had started out, in Texas. He was home, and he liked being there.”

In the early afternoon, Jane interrupted us to bring peanut butter sandwiches and milk shakes. John lost fifteen pounds in the hospital, and she’s still trying to put some meat on those old bones. While we ate, I tried to get John to talk about his historic trip down the Brazos, but we somehow got off talking instead about Henry David Thoreau, which is a sore subject with him, for reasons I’ll try to explain. The Brazos trip started as a magazine assignment from Sports Illustrated, whose editors demanded many rewrites before rejecting the story. John was teaching a course in writing at TCU at the time and still sulking about the failure of his novel; he decided the magazine piece could be a book. It was an instant success, hailed by its publisher as “a minor masterpiece.” Critics eagerly compared him to Thoreau, which seemed inaccurate to John, who refers to his predecessor throughout the book as “Saint Henry.”

“You thought Thoreau was too polemical, too preachy?” I suggested.

“I admire his best work, but I have ended up not wanting to do anything polemical,” he replied. “There’s good polemical writing, but I don’t think I would be up to it. Polemics to me destroys . . .” He paused. “I just want to write good prose. I don’t want to preach. Preaching carries its own death within itself.”

The big difference between him and Thoreau, he said, was their temperaments, in particular Thoreau’s adherence to “purity.” “I have always admired purity in others, at least when it fosters adherence to principles I agree with,” he wrote to an interviewer a few years back. “I admire it in Thoreau. But I most often distrust its symptoms in myself, because it constitutes a barrier between me and the whole messy, sinful, sensual, fallible, unpredictable ruck of humanity, of which I rather gladly know myself to be a part.”

John’s style has always been humble, however profound its effects may be. His famous trip down the Brazos wasn’t a dramatic protest but just a deep urge to see the river in its native state one final time. The Corps of Engineers and other “progressive-minded souls” had announced plans to convert the distinctive 150-mile stretch between Possum Kingdom Dam and the upper reaches of Lake Whitney into a series of small lakes. John just wanted to look at it again before it “ended up down yonder under all the Chris-Crafts and the tinkle of portable radios.” Tongue resolutely in cheek, he wrote that one can’t in conscience oppose such “praiseworthy projects” as “electrical power and flood control and moisture conservation and water skiing,” but one can regret the whole affair personally. Partly because John Graves expressed his regret in such elegant language, the project died on the drawing board. When I reminded him of that, John only smiled.

Among those who greatly admired Goodbye to a River and helped put it on the map was J. Frank Dobie, then the grand old man of Texas letters, though it took some doing to get him to read it. The story goes like this: Dobie hadn’t gotten around to reading John’s manuscript until John and Harry Jackson, a soon-to-be-famous Western sculptor, visited him at his home in Austin; John had made friends with Jackson in Spain, and both of them were big fans of Dobie’s. The old man had had a heart attack, so Mrs. Dobie extracted a promise from the younger visitors that they’d stay for only half an hour, but they got to talking and joking and drinking Jack Daniel’s and pretty soon three hours went by. At one point Dobie told John that he’d been sent a manuscript of Goodbye to a River, but he hadn’t read it because he didn’t have the time, and John told him, with customary modesty, “I don’t blame you, Mr. Dobie. I didn’t tell them to send it to you.” Dobie ended up buying one of Jackson’s pieces, and as they were leaving, he took John’s arm and said, “Now I’ll read your book.” A short time later, Dobie wrote a glowing review of the book in his syndicated newspaper column. Critics who insisted on comparing Graves to Thoreau, Dobie informed his readers, hadn’t read enough Thoreau, much less enough Graves.

John sat back for a time, finishing his milk shake, thinking about Dobie, remembering things. John has always been a quiet, hermetic sort, and Dobie was a larger-than-life raconteur, but the two men became close friends over the years, despite their differences. After a bit, John said, “One time, we were with Dobie in a Mexican restaurant in Southeast Austin, and they brought a TV over and set it down by our table, and there was Dobie on it. He was talking about something or other, and we looked at it and he waved his hand and said, ‘You know, yesterday I believed that stuff.’ ”

John slept late the following morning—since his fall he doesn’t usually get moving until about ten or ten-thirty—so Jane graciously offered to show me White Bluff Creek and some of the outlying pastures, which were covered this April with a spectacularly thick carpet of bluebonnets and paintbrushes. Though Jane is in her early eighties, she is still spry, trim, and attractive, with curly gray hair and nearly perfect bone structure. She was raised in New York City, where her mother owned an elegant boutique, Helen Cole Inc., at Seventy-first and Lexington. “My father was a Southerner who thought women should look pretty and smell sweet,” she told me. “I never shot anything except, once, by mistake, I shot a hawk.” Nevertheless, she has learned to love dirt, rock, and cactus for themselves. “It took me a long time but I finally got it,” she said. As she jumped behind the wheel of her old pickup truck, I could easily picture her sliding gracefully into a limousine or window shopping on Fifth Avenue, though probably in something more uptown than the slacks and denim blouse she was wearing at the moment.

In 1955, while she was working in her mother’s shop, Jane learned from friends about a Texas writer named John Graves who was getting ready to move to Sag Harbor. They met a short time later. “My friends had warned me not to look at his left eye because they said it was glass and had an American flag in it,” she recalled. “Of course I looked at it right away, not realizing they were joking.” In 1956 she accepted a job at Neiman Marcus and moved to Dallas, where she reacquainted herself with John. A serious courtship followed, as he showed her his beloved hills and rivers around Glen Rose. When I asked her if the cedar country came as a shock, she laughed and said, “Dallas came as a shock.”

“When we were dating, John would take me on canoe trips down the Brazos,” she recalled. “I had canoed at camp, and I had three brothers, so that part wasn’t strange. I wasn’t captivated with the river—I didn’t think about where I was until later, when I read his book—but I was captivated with John. I decided, he’s for me.” They married in New York in December 1958. Jane worked at Neiman’s until 1961, when she took leave to raise their daughters. She returned to the job when the older one, Helen, went off to Princeton and the younger one, Sally, started high school, and she continued until her retirement, in 1992.

“When John first brought me to this piece of land, it was a blazing hot day,” she recalled, steering the truck around clumps of cactus and dodging brakes of cedar. “He said we could swim in the creek and cool off, but the water was only two inches deep. I was used to the ocean. He said something about building a house. I didn’t get it until he actually started building. Then I had something to do with my hands. Yes, I began to think, we could live here—part-time.”

For years that’s what they did. During the school year, Jane and the girls stayed in Fort Worth during the week, while John worked on the house and wrote in his corner office in the barn. Gradually, Hard Scrabble became the family home. “Our idea was to teach the children that you can almost exist without a grocery store,” she told me. “We raised our own beef, froze our own fruit and vegetables in a huge freezer, milled our own flour. Except for salt and coffee and rice, we had everything right here. The girls raised and showed goats, milked them, helped them have babies. Goats were a big part of the girls’ lives. They carried them up to the house in cardboard boxes when they were newborns, bottle-fed them every four hours, sometimes took them to bed with them.” There were horses and cows too, and always dogs—Pan, Blue, many others, including Watty, a dachshund pup identified as “Passenger” on John’s famous canoe trip. “It’s hard to remember the many parts,” Jane said, brushing hair from her eyes. “It’s all a life, a whole.”

Inching the truck down a steep, muddy grade toward the creek, she said, “I hope we can get back up.” So did I. To my surprise, she began driving along the limestone bed of the creek, which, except for a few pools, was only a couple inches deep. She parked the truck on a rock ledge, just above a four-foot-high waterfall. “This is where we come in the summer when our children and grandchildren are here,” she said. “It changes every year. Sometimes after a big rain, those huge rocks you see down below us are underwater.”

We stood on the limestone ledge for a time, listening to the roar of the falls, enjoying the perfect peace of country life. “One of these days,” Jane said, directing my attention to some rocks the size of trucks that seemed to balance on the cliffs behind us, “those giant rocks will tumble into the creek and be washed away.” One of these days, I thought, we all will.

It took her four runs before she got the truck back up the muddy incline.

While John ate breakfast, I asked him some questions that had been bothering me. Reviewing my notes the previous night in one of the Graveses’ upstairs bedrooms, I had been troubled by some of his remarks about his native land. He had talked about his indifference to all things Texan until his accidental return to nurse his dying father, at which time he saw the land with new eyes. I also recalled a line from Goodbye to a River, where he said that Texans had lost their “organic kinship to nature.” I wondered if he considered the loss permanent.

“What are your feelings about Texas today?” I asked.

“Maybe it’s a sign of old age, or decrepitude, but I’m not very optimistic about the future of this country,” he said, sipping his coffee. “People here, they weren’t what you’d call an admirable hunk of American society, but they had their own ways, which I got used to. They were a distinctive variety. But that’s all been wiped out. It used to be that the differences among people were big, and those differences always interested me greatly. But now I find a lot of sameness. I don’t like the way things are shaping up.”

He drank some more coffee and looked out the window. “I’ve written about this,” he said, directing me again to the Meinzer book, where he had observed in his introduction, “Differences in modes of human work, play, manners, language, and even appearance have fascinated me forever, and I have come to believe that these differences not only hold rich and interesting color and drama but are a stout force in the possibility of humankind’s endurance on this planet, for as Darwin knew, variety fosters survival.” He nodded. “I still feel that way,” he said.

And if it’s true, at least John has done his part, holding fast to his particular view of the world in his particular place, never claiming too much for his work other than that it was his and his alone. In a long writing life he has put only a handful of books on the shelf, but the ones he has put there are powerfully informed by his activities away from the desk, in a way that few other writers come close to. Who but John could have prefaced a book with these lines, from Hard Scrabble: “If at some point in his perusal of this book a perceptive and thoughtful reader should ask why in the hell . . . anyone even half aware of the currents of the world would choose to spend heavily out of his allotted time on such archaic irrelevancies as stonemasonry, the observation of armadillos, vegetable gardening, species of underbrush, and the treatment of retained afterbirth in ruminants, with very slight expectation of even crass cash gain, he will be asking the same thing I have often asked myself.”

Nowadays, life at Hard Scrabble has become too sedentary to include much of those archaic irrelevancies. John is too old and feeble to hunt or fish, much less clear cedar. He could, if he chose, sit on the creek bank with a cane pole, but that’s never been his way. There hasn’t been a dog on the place for years. He misses them, like he misses a lot of things that were once natural and everyday. He will celebrate his ninetieth birthday on August 6, though “celebrate” isn’t the word he would use.

There were other questions I had intended to ask, but I knew it was time to go. John needed to get back to his office, back to work, back to his book about friends. It’s a typically idiosyncratic project, which he describes as “just an alphabetical list of people who’ve meant something to me in my life. What happened between us, what we did together.” The office is his sanctuary. “I leave him alone in there,” Jane says. “It’s his room, his computer, his printer, his books.” When the weather is good, he sleeps in a bed on the office porch, close to his work. Work is what he has left. Work is who he was, who he is, who he always will be.

By the time I was packed and ready to leave, John was already lost deep inside his current composition. “Drive safely,” Jane admonished. The gate opened automatically as I pulled up in my car. Camped in the road ahead, six turkey vultures were cleaning up the remains of a small animal. One of the steers from a pasture of Longhorns had found an opening in the fence and gave me a look of supreme indifference before resuming his meal of roadside vegetation. The narrow gravel road back to the highway hugged the creek. Just past the low-water crossing, I stopped and climbed out of the car and stood there a good five minutes, savoring the essence of this lost place, drinking down its sounds. Finally, reluctantly, I turned south toward home. Walnut Springs, Meridian, Clifton, Valley Mills, each small town opened one eye as I passed by, as slowly as the law allowed.