The parents of artist Carlos Ramirez, whose public art installation Altar to a Dream is on view through February 14 in downtown Dallas, were born in Mexico, came to the Rio Grande Valley area as teenagers, and traveled across the United States as young adults, following the harvests. As they drove through states like Texas, Oklahoma, and California in a 1951 Studebaker, they nurtured a young family (Carlos and his two older sisters spent much of their childhoods on the road) and a dream of prosperity and belonging, while keeping one eye peeled for unfair bosses and anti-immigrant sentiment.

Sometimes the car was their home for the night. “They would never stop at hotels because they never knew if people would be hostile to them or friendly,” Ramirez explains. “They would go through word of mouth—other immigrants who would share locations or places that were safe.”

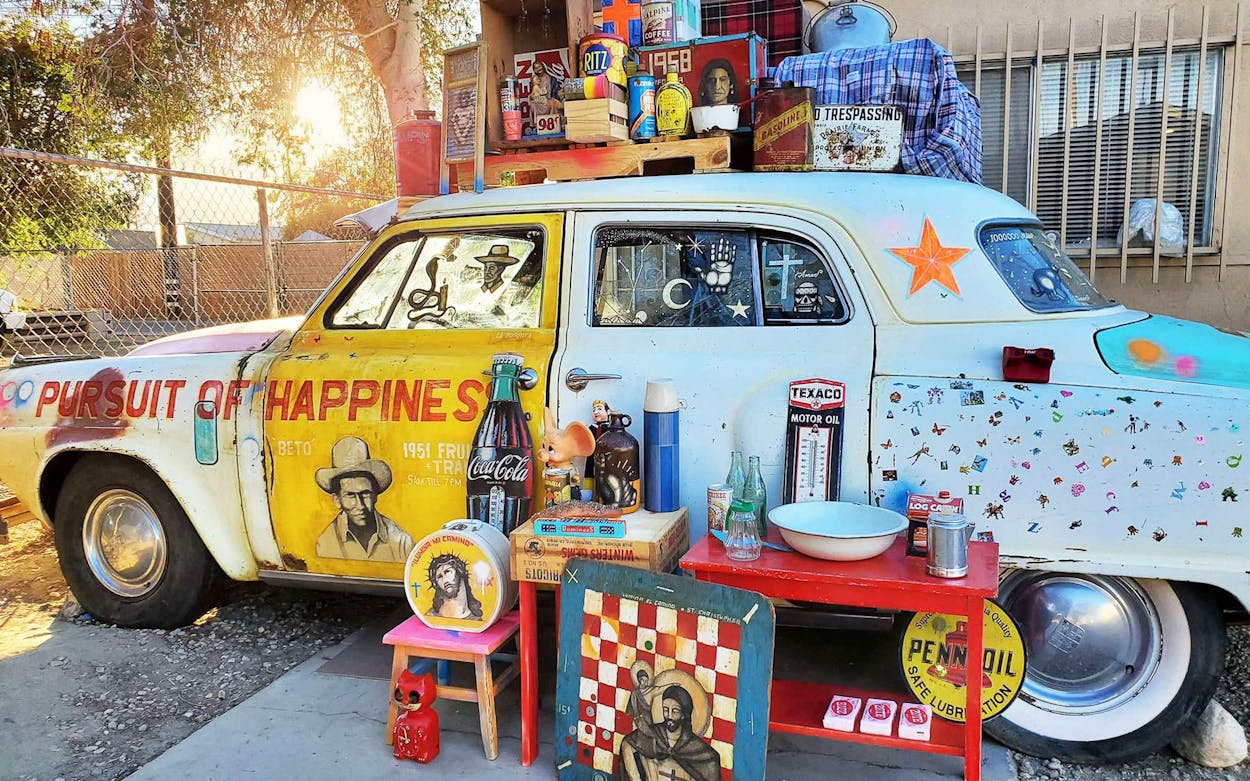

For Altar to a Dream, Ramirez has installed a 1951 Studebaker, similar to the one his parents once drove, in the heart of downtown Dallas, adding colorful and meaningful decorative touches. Around the car are three small tables invoking the homemade altars often seen in Mexican and Mexican American homes. Ramirez’s altars feature found-art assemblages of religious icons and vintage brand-name detritus. One table, for example, is made partly of an upside-down crate advertising apricots from Sacramento, California. The table holds Zote soap, bread, Alpine and Taster’s Choice coffee tins, a thermos, and a decorated bottle of Clorox. To one side is a metal lunchbox with a picture of Jesus and the phrase “Illumina Mi Camino” (“light my way”). To the other side is an item that carries special weight for Ramirez: a hundred-year-old vintage checkerboard decorated with an image of Saint Christopher, the patron saint of travelers.

“My mother would tell me how crisscrossing the United States in mid-century America was like crossing a checkerboard, that you never knew when you were going to land on a friendly spot or an unfriendly spot,” he explains.

Many details of Altar to a Dream were inspired by stories Ramirez heard from his mother, who picked grapes, onions, grapefruits, and other crops, and who joined the 1960s United Farm Workers labor fight with César Chávez. Ramirez’s father, who passed away two decades ago, is also present in the work, as a 19-year-old, in a crosshatch portrait painted on the door by the driver’s seat, where Ramirez remembers him sitting. The back seat of the Studebaker is an even more personal realm for Ramirez; he’s decorated the outside with kids’ stickers and fanciful images of constellations in white paint.

“I thought I’d pepper it with small images, as an ode to all of the young children that have to work at early ages out there in the fields,” Ramirez says. “I remember riding in the back seat, looking out the window and letting my imagination just wander.”

Altar to a Dream is part of PBS’s American Portrait initiative, a multimedia storytelling project including both a broadcast TV docuseries and public art displays around the country in celebration of the network’s fiftieth anniversary. Other public art exhibits funded by PBS for this project include a mobile art exhibition in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by Rick Lowe, founder of Houston’s Project Row Houses, to engage residents with the history of the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, in which at least 26 Black Tulsans were killed.

Ramirez says he talked with American Portrait and partner organization RadicalMedia about several locations for Altar to a Dream, including sites in San Francisco and Los Angeles. He decided on downtown Dallas because of Texas’s importance to his family, and because it is the place where John F. Kennedy was murdered. For Ramirez, both Kennedy and his assassination are closely linked to the civil rights struggle. Altar to a Dream is a work of outdoor public art, but the car is protected by a red-rimmed plexiglass box, which may for some invoke thoughts of Kennedy’s final, unshielded motorcade.

Altar to a Dream is installed in a small private park on Main Street across from boutique hotel The Joule, in front of another, more permanent public art installation, sculptor Tony Tasset’s Eye, better known to Dallasites as the selfie-magnet “giant eyeball.” It’s a strange juxtaposition of artistic styles, but Ramirez says he likes the proximity. During Black Lives Matter protests last summer, Eye was vandalized with the spray-painted phrase “NOW UC US,” and local artist lauren woods (who spells her name in all lowercase) called for the graffiti to be left intact in order to remind future selfie takers of the unfinished struggle to end systemic oppression, calling the blue-irised eye sculpture “symbolic of the surveillance state and white supremacy.” The graffiti has since been removed.

The Dallas-based oil, hospitality, and service-industry giant Headington Companies, which owns The Joule and Eye, is the location sponsor for Altar to a Dream. Ramirez’s work can now be understood as part of the ongoing conversation on the site. “Where we are today, as America, I think there’s still a reckoning, or there’s still a lot of healing to be done,” Ramirez says. “I think it fits well there because of that.”

To the extent that his work has a political message for our times, Ramirez points to the phrase emblazoned in red paint across the front half of the Studebaker: “PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS.”

“I was thinking about today’s social climate, how crazy it’s becoming, how chaotic,” Ramirez says. “I thought that phrase fit perfectly, just to illustrate what it took for so many different people—regardless of where they’re from, what color they are, or anything like that—to establish their legacies, and how America was shaped also by them. I thought: The pursuit of happiness applies to everyone.”