A light drizzle was falling in the early morning hours of May 9, 2010, when detective Dwayne Thompson pulled up in front of a modest home on Spring Grove Avenue, in a tree-lined neighborhood in North Dallas. A uniformed officer walked over and told Thompson that the house belonged to a man named Michael Burnside, age thirty. At around twelve-thirty, the officer continued, a woman had called 911 from the house. She identified herself as Olivia Lord, Burnside’s girlfriend, and said she had just found Burnside lying on the kitchen floor with a gunshot wound to his head. When the paramedics arrived, Burnside had faint vital signs, but he died shortly after reaching the emergency room at Parkland Memorial Hospital.

The officer pointed to a woman sitting on a chair in the front yard, her face in her hands. She was wearing a blue T-shirt and gray sweatpants, her knees stained with blood. That’s Olivia Lord, he told Thompson. The officer looked at the notes he had jotted down. Lord was 33 years old and worked as a loan officer for a mortgage company. She had started dating Burnside, the co-owner of a company that retrofitted homes to make them energy-efficient, about a year earlier. The way Lord had described it, she and Burnside were deeply in love, and they had been talking about marriage. Although she had her own apartment, she was planning to move in with him as soon as he finished remodeling the house.

“So what happened?” Thompson asked.

The officer flipped a page in his notebook. Lord said that she and Burnside had gotten into an argument—something about a birthday party. She said Burnside had been drinking heavily, and at some point, in the midst of the fight, he had walked into the kitchen and shot himself. The officer shrugged.

“Who’s that?” Thompson asked, pointing to a man kneeling beside Lord in the front yard. He was wearing a T-shirt, khaki shorts, and sandals. The officer identified him as Brian Jaffe, a thirty-year-old civil engineer who had been Burnside’s best friend since high school. The officer flipped another page. Jaffe said he had been at the house earlier that evening, helping Burnside install a dishwasher while Lord was painting the doors and baseboards, and that he had left before midnight. After arriving at his house, which was a ten-minute drive away, he had received a call from Lord. She was so hysterical he could not understand what she was saying. Jaffe said he had sped back to Burnside’s home, arriving at the same time as the paramedics.

Thompson studied Lord and Jaffe for a moment, then walked over to them. The detective was 47 years old and built like a linebacker at six feet two inches and 230 pounds. He had on a dark fedora, a dark suit, a white shirt with a tie, and dress shoes. Strapped around his shoulders was a thick brown leather holster that held his department-issued pistol, a 9mm Sig Sauer. After telling Lord and Jaffe that he was sorry for their loss, Thompson asked them to sign releases agreeing to gunshot residue tests—routine procedure, he assured them. He then asked them to ride down to Dallas police headquarters in separate squad cars to give their statements. Between sobs, Lord begged to be taken to Parkland to be with her boyfriend. “That won’t be possible,” said Thompson. He noticed that there was a chemical odor—it smelled like bleach, he would later say—on her clothes.

Jaffe and Lord were taken to the station, and Thompson headed inside Burnside’s home. He walked into the kitchen and nodded at Dale Lundberg, a detective who was on call that night to work as Thompson’s backup. On the floor was a pool of blood along with bloody towels. Scattered around the floor were a few bottles of household cleaning products. A 9mm Beretta was also on the floor about five feet from where Burnside’s body had been. A bullet hole was in a wall near the ceiling.

Thompson and Lundberg started talking. Why the bottles of cleaning products and the bloody towels? And if the young man had shot himself, wouldn’t the gun have landed closer to his body? There was something else that didn’t seem right: drops of blood leading into another room. He told Lundberg that he wasn’t sure this was a suicide. There were too many unanswered questions, he said. Something did not add up.

Thompson returned to headquarters and took the elevator to the homicide offices on the fifth floor. A couple of clerks grinned at him. He is one of the most popular detectives in the Dallas Police Department—“a charismatic man, big and boisterous, with a powerful deep voice,” says Craig Miller, a former deputy police chief who served as Thompson’s lieutenant in the homicide unit in 2010. Raised in Ohio, Thompson spent five years in the Army, earning the rank of captain and commanding a military police unit in Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Storm. After being honorably discharged, in 1991, while stationed at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, he joined the Dallas police. He first worked in patrol, where he was assigned to some of the city’s tougher neighborhoods, and then spent ten years as a detective in the robbery and property crimes division before being promoted to homicide, in 2007.

One of the few black detectives in the unit, Thompson quickly made his mark. “Let’s solve some murders, my brothers,” he would cheerfully bellow as he barreled into the office at the beginning of his shifts. “Let’s make a bad thing right.” His fellow detectives nicknamed him D-Train. They liked to say that when he pursued a suspect, he was as unstoppable as a locomotive. In 2008, when the producers of The First 48, a reality series on the A&E network about homicide detectives in big-city police departments, came to Dallas to film some episodes, they were riveted by Thompson. Cameras followed him as he solved a murder case in which the body was never found. That was one of the most-watched episodes in The First 48’s run, drawing 2.3 million viewers, and the producers told Thompson that they wanted to do more shows with him. He was so compelling in front of the camera—cajoling witnesses to open up and then lashing out at a suspect—that he looked like a television actor playing a detective.

When he wasn’t solving murders, Thompson restored sports cars and tooled around in a black Corvette convertible. (As he said in one interview for The First 48, “Bringing stuff back to life is what’s up, Jack.”) He taught classes at the Dallas Police Academy, and a private training agency hired him to lead seminars on detective work around the country. In his lectures, he often told other officers that to find out why a killing had taken place, it was as important to study the life of the victim—“victimology,” he called it—as it was to study the behavior of the criminal. He often said that victimology was the most overlooked part of a homicide investigation even though it could help explain whether a suspect was guilty or innocent.

And on this morning, Thompson was especially interested in the victimology of Burnside. Why, he wanted to know, would a man suddenly shoot himself after what seemed to be a routine argument with his girlfriend?

Thompson stared at a copy of Burnside’s driver’s license. He had been a good-looking young man, with a magnificent, wide grin. He’d been as tall as Thompson, with a lean, athletic build. Thompson picked up his cellphone and called Burnside’s father, John, a successful Dallas business analyst. John, who had already been informed by Jaffe about the incident, could barely maintain his composure. He told Thompson that his son had had the most positive personality of anyone he had ever met. He said that Michael had called earlier in the week, telling his mother, Cindi, that he was looking forward to coming over to their home for lunch on May 9, which was Mother’s Day. “There’s no way my son shot himself,” John said.

Thompson asked if there was any chance that Jaffe had been carrying on a secret relationship with Lord. Was there a chance he was involved in the shooting? John said that was impossible—Jaffe would have never betrayed Michael.

Thompson thanked John and told him he would be back in touch. An officer came over to Thompson’s cubicle and handed him Lord’s and Jaffe’s cellphones. He studied the call histories on the phones and took some notes. Then his own cellphone rang. It was Lundberg, who had gone to Parkland to examine Burnside’s body. Lundberg said that there was a gunshot wound to his right temple, a contact wound where the muzzle had been pressed directly against his head, which is common in suicides involving a handgun. There was no sign that he had struggled with an assailant—no bruises or scratches on his skin, no scuffed knuckles.

But, said Lundberg, there was no sign of blood spatter on Burnside’s right hand or arm. And the bullet had exited toward the top of the left side of Burnside’s head. In a typical suicide, he said, when someone shoots himself in the temple, he points the gun straight at his head and the bullet travels through the brain and exits in a line roughly parallel to the floor. Thompson asked Lundberg if he thought it was possible that a person who was much shorter than Burnside—someone, say, who was five feet two inches tall, the height of Olivia Lord—could have aimed the Beretta at a 45-degree angle toward Burnside’s head and pulled the trigger?

Yes, said Lundberg.

Something is definitely not adding up, Thompson thought, as he walked into one of the interview rooms where Brian Jaffe was waiting.

Jaffe was sitting in a plastic chair next to a small table pushed against a wall. Thompson sat in another chair and asked about Burnside. Jaffe told him that “Mikey” was a “good ol’ boy” who liked hunting and fishing. As for Burnside’s relationship with Lord, Jaffe said, “It was one of those old-school-type things. She cooked, she cleaned, he was happy.”

“Was she Miss Right or Miss Right Now?” Thompson asked.

“She was Miss Right as far as he was concerned,” Jaffe replied. But, he added, his friend “wasn’t the type to get married at any point.”

Jaffe said that he and Burnside had been drinking earlier that evening. (Jaffe had been drinking Shiner Bock, and Burnside had been having Red Bull mixed with vodka.) They couldn’t get the dishwasher installed because of a broken valve, which sent water all over the floor, so they took a break. They began talking about planning a surprise birthday party in a few weeks for one of their friends and flying to Las Vegas later that summer to attend a bachelor party for another. According to Jaffe, Lord overheard the conversation and “started to get upset.” She told Burnside she was hurt that he would go to the trouble of organizing a friend’s birthday party when he had done next to nothing for her own birthday a few months earlier. What’s more, she didn’t want him to go to Las Vegas for a bachelor party.

“Basically she said, ‘I know the kind of stuff that goes on in Vegas,’ ” Jaffe told Thompson. “Mikey said, ‘I’m not going to cheat on you in Vegas. Don’t worry about it.’ ” Although the couple appeared to be joking, said Jaffe, “you could tell they were serious.”

At that point, Jaffe said, he decided to leave, and when he returned after getting the frantic phone call from Lord, he found her in the front yard. “Olivia kept saying, ‘I wasn’t going to leave him. I wasn’t going to leave him. It was a stupid fight.’ ”

Jaffe paused. “Brian, we got a problem,” Thompson said. “Something happened there tonight, and it doesn’t make sense.”

“The only thing I can think of is that he was careless sometimes with guns,” Jaffe said. “Sometimes he would think [a gun] was unloaded and he would swing it around, you know, not trying to hurt anybody, just being stupid. And you’d say, you know, ‘That’s not a toy.’ ”

Jaffe said that Burnside had pulled out a gun that night. “We were joking around about something—I don’t remember what—and I said, ‘Hey, where’s your Beretta?’ And he opened up [a kitchen drawer] and said, ‘It’s right here.’ ”

But, Jaffe added, Burnside didn’t wave the gun around. He also said he had seen Burnside act recklessly with a gun only two or three times over the past fifteen years.

Then Jaffe added one more detail. “I’ll tell you this about Mikey: his motto was ‘I love my life.’ Every time something worked out, he’d be like, ‘I love my life.’ ” In fact, Jaffe said, Burnside had used that very phrase that evening because his company was about to bill $70,000 for work it had done in a single week. “He was not a depressed type of person at all. He was the life of the party.”

Thompson left the room, walked down the hall, and opened the door to another interview room. Lord was slumped over in a chair, still wearing her blood-stained clothes. It was now 5:44 a.m. Her voice shook when she spoke. She told Thompson that she too had been drinking that night, a mix of vodka and sweet tea.

And, yes, she said, she had grown irritated when she heard Burnside and Jaffe talking about the birthday party. “I was picking at him all night long about that,” she said. After Jaffe went home, the argument escalated. Burnside told her that he was under financial stress, having to pay both his mortgage and his income taxes. According to Lord, he became “obnoxious” and “sarcastic,” which often happened when he drank.

Tired of fighting, she stopped talking to Burnside and went into the bathroom to take off her makeup. But he stayed in the bedroom, “pacing, walking around, yelling at me, screaming, angry.” Finally, after he couldn’t get her to respond to him, he left the room.

“I heard what I thought was glass shattering really loud,” Lord said. “I went into the kitchen and he was on the floor and there was blood. I grabbed him and held him.”

Thompson looked at his notebook, where he had written down the calls Lord had made on her cellphone. He asked her why, after finding Burnside on the floor, she had first called Jaffe but then waited seven minutes before calling 911. Lord seemed shocked. She said that she had phoned Jaffe because she initially thought Burnside had fallen and was hurt. But when she realized how serious his injury was—“I think I saw a spot on his head,” she said—she called 911 several times.

Thompson asked why there was so little blood on her hands and arms. Had she washed up with towels before the paramedics and police arrived? “No,” said Lord.

Had she touched her boyfriend’s gun? “No,” she said again.

Thompson said he had heard that Burnside was making money. “He wasn’t stressed-out,” Thompson said.

“I know verbally from him that he owes the government a lot of taxes,” Lord replied. “It was a very overwhelming issue.”

Thompson leaned back in his chair and stared at Lord. “We’re missing something,” he said to her. “Something is not right.”

He allowed a few seconds to pass. He asked her again about what she was doing during that seven-minute gap between phone calls in the house that night.

“I was leaning over my future husband’s body,” Lord said.

And then Thompson pounced. “You f—ing shot him!” he bellowed, nearly coming out of his chair. “That’s what you did! You shot him!”

Lord’s mouth fell open. “No, I did not!”

“Olivia, you’re not telling me the truth.”

“I’m telling you exactly what happened!”

“You’re arguing about a goddamn birthday party, and he says, ‘I’m so upset about the goddamn birthday party that I’m going to kill myself’?” Thompson said, his voice growing louder. “How are you going to explain that to his family? You think they are going to accept this bullshit you are giving me?”

For the next hour, Thompson continued to berate Lord, trying to get her to crack. But she never did: she kept saying that she loved her boyfriend, that they were happy together, and that he had taken his life for reasons she could not imagine. “I’m just as baffled as you are,” she said. “Do I want to know an answer? Yes. Do I feel an overwhelming feeling of guilt because I may have provoked something? Yes. I’m devastated.”

Thompson bore down. “Who do you think you are? Who do you f—ing think you are?”

“I’m a person who just lost her boyfriend,” Lord wailed.

“And I’m a person who thinks your behavior tonight doesn’t add up.” He pointed his finger at her. “If I discover anything that substantiates what I believe, I’m going to charge you with murder.”

He glared at her for a moment. “I do believe you killed him. I believe that with all my heart.”

Thompson stormed out of the room and asked Lundberg to see what he could get out of Lord. Compared with Thompson, Lundberg was a quiet man who wore glasses and spoke slowly. In his free time, he read Civil War history and played Internet chess. Lundberg walked into the interview room, pulled his chair close to Lord, and played the role of the good cop. He spoke to her the way a loving father would talk to his daughter.

As he nodded sympathetically, she again talked about how hurt she had been on her birthday. She added a detail about their relationship that she hadn’t told Thompson, saying that she had been disappointed that Burnside hadn’t proposed to her the previous Christmas. She also said that when he got angry, he could be “a little scary” and that he threw “stuff in the house.” She would usually ignore him when he got into one of his moods, but this time it had only made him angrier.

Lundberg gently brought up the bloodied towels in the kitchen, asking if she had used them to wipe blood off her body. No, Lord said. The towels had been on the floor to soak up the water that had spilled when the dishwasher valve broke. Lundberg then brought up the trajectory of the bullet through Burnside’s brain. His voice got even softer. “We’ve been detectives for a long time, and we understand that sometimes things happen and we can’t always control the situation,” he said. “We understand that people get upset, get scared, get angry—and when all those emotions are happening at once, people do things.”

He paused and kept his eyes on Lord. “At Christmas, you thought you were going to get a ring. You were very disappointed. And now you have this thing where he was spending a lot of money on his friend, but he didn’t spend near as much money on your birthday. And that’s hurtful. . . . You said he was upset and he hollers and starts getting destructive, and the thing is, you said he gets scary. . . . Based on what we see, it looks like you got upset and shot him. Because that is the only thing that makes sense.”

Lord shook her head. “The only thing I can tell you that might make any sense to anybody is that when he’s drunk, he’s very irrational,” she said.

“Olivia, everyone we talked to said one consistent thing about Michael: that he loved life.”

“He did love life. We loved our life together.”

Lundberg paused again. “And now he’s dead,” he said.

Lord spent the next four days at her mother’s home in the Dallas suburbs, lying in bed, taking sleeping pills. She’d given her telephone to her aunt, who was screening her calls. Her father, who lived in California—he and Lord’s mother had divorced when she was a child—flew in to be with her. She told her parents that Thompson had brutalized her. Every time she tried to answer a question, she said, he cut her off and called her a liar. At the end of the interrogation, he had discarded her “like trash.”

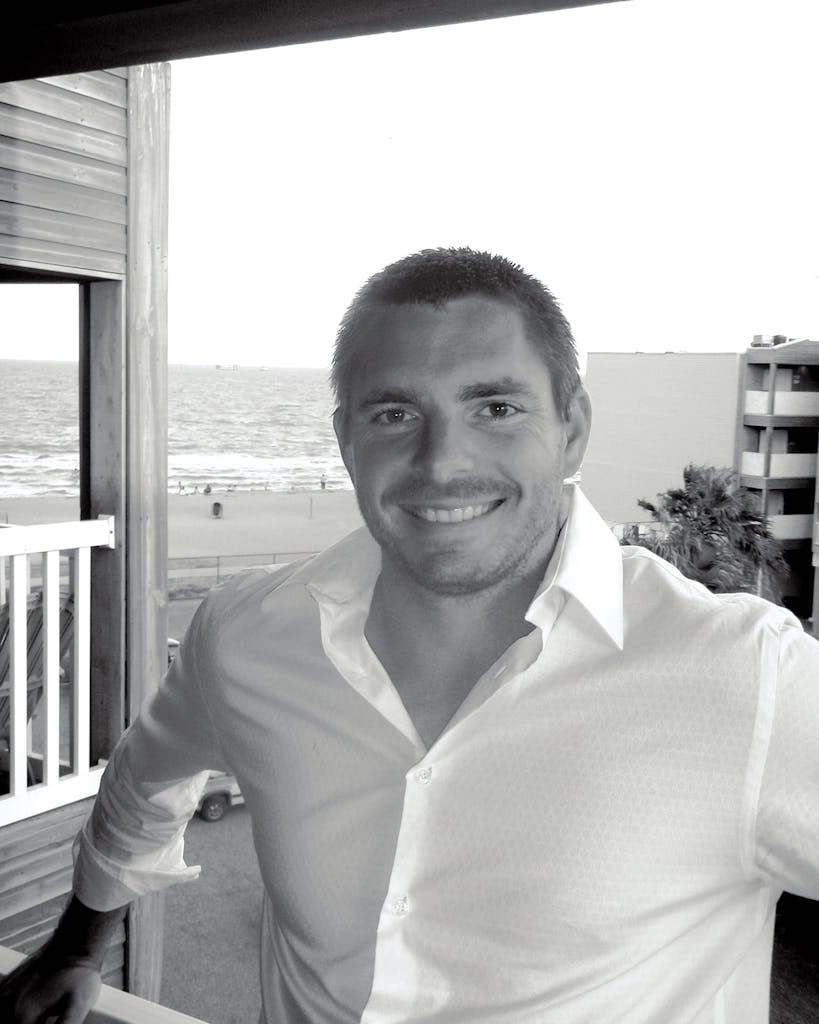

Lord is a striking green-eyed woman, with wavy auburn hair that sweeps down past her shoulders. She grew up in the Dallas area and after graduating from high school, she went straight to work, leasing apartments for a large real estate company and later selling cosmetics at Neiman Marcus in NorthPark Center. During her twenties, she always seemed to be out and about, a regular at trendy nightspots and concerts. In October 2008 a mutual friend introduced her and Burnside at a small bar on Dallas’s Lower Greenville Avenue. By that time, Lord was working as a loan officer, and although they were both romantically involved with other people, they were clearly attracted to each other. Several months later, when he called Lord to refinance his home, their other relationships had ended. He took her to dinner, and the date lasted the entire weekend.

Lord told her friends and family that Burnside definitely liked to have a good time. She said that he was a big drinker and that he could sometimes be reckless. Burnside had been involved in a couple of accidents. He also had run up some debt: he owed a rental car company money for crashing one of its vehicles, and he had received letters from the IRS demanding that he pay more than $50,000 in back taxes.

But Lord insisted he had a good heart. He was confident and charming, she said. She liked pampering him, waiting on him hand and foot so that he could focus on building his company. She helped him with his finances, reminding him to pay his bills and to keep his spending in line. She was so in love with him that she was always able to forgive him when he screwed up—like the night of her birthday, when he got rip-roaring drunk, staggered around the restaurant, and didn’t even pay for dinner. There was no question in her mind, she said, that she and Burnside would soon get married.

On May 14, five days after the shooting, Lord finally left her mother’s house to attend Burnside’s funeral with her family and friends. She walked to the front of the chapel to look at Burnside in his casket, and her legs nearly buckled as she said his name. After the service, she told Burnside’s friends that she hadn’t returned any of their calls because she had been overwhelmed with grief. But she was pointedly not invited to a get-together that Burnside’s friends were throwing after the service at one of his favorite bars. By then, a couple of those friends had talked to Thompson, and he had made it clear to them just what he thought of Lord: he said he would stake his career on his belief that she had killed him.

Nor did Burnside’s parents invite her to the reception. They too had been talking to Thompson and they were furious. A few days after the funeral, Lord called Burnside’s brother to ask if she could retrieve some of her belongings from the house. Burnside’s father showed up to let her in, and when Lord tried to tell him she had not murdered his son, he cut her off. “Why did you wait seven minutes before calling 911?” he yelled. “Why did you let my son bleed to death on his own kitchen floor? I hope you die in jail and burn in hell!”

For the rest of the month, Burnside’s father regularly called Thompson to get updates on the investigation. The detective told him that he was doing what he could. What he didn’t say was that the case was going nowhere. A lab technician had been unable to find any fingerprints on the Beretta because the gun had been covered in blood. Thompson also had not told the Burnsides that he had misread a crucial piece of evidence. The day after the shooting, he had checked the records and discovered that there was no seven-minute gap on Lord’s cellphone between the calls to Jaffe and 911. In truth, she had called 911 seconds after she had tried to reach Jaffe.

Nevertheless, as far as Thompson was concerned, that did not eliminate her as a suspect. In his opinion, it was perfectly plausible that in the heat of the argument with Burnside, she had taken his pistol, slipped up behind him, and pulled the trigger. She had then grabbed the bottles of cleaning products from under the sink to wash away the blood and the gunpowder residue, which would account for the chemical odor he thought he had smelled on her. And, Thompson guessed, she had wiped down her hands and arms with the towels he had seen on the kitchen floor.

Still, Thompson had only a theory. What he needed was irrefutable evidence pointing to Lord’s involvement in the shooting. By the first of June, he’d put aside Lord’s file to work on his other cases. Then, on June 5, his phone rang. It was Burnside’s father. In an excited voice, he said that he had been told by his son’s next-door neighbor that a neighbor who lived across the street—an attorney named Sheida Rastegar—had information that linked Lord to the killing.

Thompson and Lundberg drove to Rastegar’s house. The lawyer was reluctant to open the door. Finally, after Thompson barked at him, he stepped onto the front porch and told a flabbergasting story. According to Thompson, Rastegar said he had been in bed during the early morning hours of May 9 when he heard screaming in Burnside’s front yard. It was Lord. Rastegar ran outside and asked her what had happened. She fell to her knees and said it was an accident and that she didn’t mean to shoot him.

When Thompson asked why he didn’t immediately tell that story to the police, Rastegar replied that the uniformed officers who first arrived at the scene had rudely ordered him to go back to his home before he had a chance to say anything. Thompson told Rastegar to go to the station and make an official recorded statement, which Thompson later used to obtain an arrest warrant charging Lord with murder. He called Jaffe, who had also turned against Lord, to see if he could help him locate her. Jaffe called Thompson back the next day and said that he had reached Lord. She was on an airplane—on her way to California. She had told Jaffe she had driven past Burnside’s house before leaving and had seen crime scene investigation vehicles parked outside. She wanted to know why they were there. For Thompson, there was no question about it: Lord was on the run.

A team of U.S. marshals found her at her father’s home in Palmdale, about an hour north of Los Angeles, and Lord was held in custody for nine days. She appeared to be so despondent that a jailer thought she needed to be put on suicide watch. “I’m innocent,” Lord kept saying. “I’m innocent.”

Her parents hired an attorney named Joe Shearin, a former guard for the University of Texas Longhorns who had played in the NFL before becoming one of Dallas’s most prominent criminal defense lawyers. Shearin called a friend in the homicide unit to ask about Thompson, whom he had never met. Thompson just happened to be standing at the detective’s desk, and he was more than happy to talk to Shearin. He said that based on Burnside’s victimology, there was no way that a young man with a bright future would put a bullet in his brain simply because his girlfriend was peeved at him. And now that he had a witness who was going to provide “bombshell testimony” about what had really happened that night, he was ready to go to trial.

Shearin got Lord out of jail on bail. She had always insisted that she had not fled from the police. In fact, she had purchased the airline tickets for herself, her nieces, and her nephew to go to California thirteen days before the arrest warrant had been filed. When she flew back to Dallas, she went straight to Shearin’s office. He asked her about some of the puzzling physical evidence that had been found at Burnside’s home the night of the shooting. Why, for instance, were there bottles of cleaning products scattered on the kitchen floor? Lord explained that Burnside had taken them out from underneath the sink when he was trying to install the dishwasher. She certainly had not used them to wash herself off, she said. If the detectives thought they had noticed the smell of chemicals on her, it must have come from the paint thinner and the floor stripper that she and Burnside had been using that day.

Shearin questioned Lord about the drops of blood around the house. She explained that after she had found Burnside, her calls to 911 kept getting dropped due to a weak signal on her cellphone. She had desperately run from room to room trying to get better reception. His blood must have dripped off her clothes.

Shearin then asked if she was included in Burnside’s will or his life insurance policy. Of course not, she said.

Shearin ordered Lord’s cellphone records and received more good news: there was no seven-minute gap in her calls. (Thompson still hadn’t told anyone outside his office about the discrepancy.) Shearin paid a visit to Reade Quinton, the medical examiner who performed the autopsy on Burnside, to ask him why, just prior to Lord’s arrest, he had changed his ruling about the cause of death from “pending” to “homicide.” Quinton replied that Thompson had informed him about the statement made by Rastegar. Thompson had also told him that he believed there was blood spatter from the gunshot on Lord’s clothes, which meant that she could not have been in the bathroom at the time of the shooting, despite what Lord had said in her interview.

Shearin asked if Thompson had mentioned that an inebriated Burnside had shown the Beretta to his friend that night. (The autopsy report revealed that he had at least a .17 blood alcohol level when he died—twice the legal limit to drive a vehicle.) Or, asked Shearin, did Thompson say that Burnside was stressed about owing money to the IRS?

No, said Quinton, Thompson hadn’t mentioned either of those things.

In August, three months after the shooting, Shearin requested an examining trial, a legal procedure in which a police officer must appear in a magistrate’s court to lay out the probable cause for the arrest of a suspect in a felony case. Thompson testified that Lord had little blood on her hands and that she smelled “of cleaning solution,” which led him to believe she had washed her hands. When Shearin asked if he had told anyone that there was blood spatter on Lord’s clothing, he replied, “I may have said it, but I don’t know whether I said it or not.” Shearin then asked about the trajectory of the bullet through Burnside’s skull. Thompson formed his hand into the shape of a gun and pointed at his jawline, aiming upward at a 70-degree angle, which infuriated Shearin, who accused Thompson of wildly exaggerating the location and angle of the shot.

The judge ruled that there had been probable cause to arrest Lord, though the testimony in the examining trial did little to prove or disprove Lord’s guilt. When the lab report on the gunshot residue was completed, it wasn’t much help either. It found that “two particles characteristic of primer gunshot residue” had been discovered on the back of Burnside’s right hand and that “one particle characteristic of primer gunshot residue” had been discovered on the back of Lord’s left hand. Another particle had been discovered on the front of Lord’s shirt. The report could be interpreted several ways: Maybe, as Shearin believed, after Burnside had pulled the trigger, some of the gunshot residue had been transferred onto Lord when she held him in the kitchen. Or maybe, as Thompson theorized, Lord had missed some of the residue on her hand and her shirt when she cleaned herself up after pulling the trigger. Or maybe the two had struggled for the gun before it went off, leaving residue on both of them.

When Quinton studied the gunshot residue report, he concluded that the trace amounts of residue on Lord “did not necessarily indicate handling or firing the weapon.” But he couldn’t say for sure that she didn’t fire the Beretta. As for the question of blood spatter on Lord’s clothes, however, Quinton did have a definite opinion. He saw no “high-velocity” blood spatter. He was convinced Thompson had misled him, and on September 22, Quinton changed the cause of Burnside’s death to “undetermined.” Quinton’s new ruling was definitely a boost for Lord’s case, but it was hardly enough to guarantee an acquittal.

Then Shearin got his big break. Toward the end of the year, he finally saw the video recording of Rastegar’s interview at police headquarters. Lundberg conducted the interview because Thompson had a prior commitment to teach a class at the police academy. In the video, Rastegar initially seemed to confirm what he had supposedly told Thompson and Lundberg on the porch. He said when he came up to Lord in the yard, she fell to her knees and “said something to the effect of ‘He’s dying.’ ” Rastegar told Lundberg, “I got the impression she was trying to tell me it was accidental. That she didn’t mean to do it.”

As the interview continued, however, Rastegar said that he wasn’t certain what he had heard. “I don’t remember the exact words that were used,” he told Lundberg. “I’m not even sure the word ‘accident’ was used.” He said he later “surmised” that Lord had shot Burnside because he had heard a story going around the neighborhood that Burnside had been shot in the back of the head, which would suggest he had been murdered. By the end of the interview, Thompson had returned from his lecture and walked into the room. Rastegar again tried to explain what he had heard Lord say that night. “I had the impression that she told me that [Burnside] had nothing to do with it and she did it.” But he refused to say, like he had said on his porch, that he had definitely heard Lord confess to the shooting.

Shearin was outraged. The arrest affidavit had never mentioned that Rastegar had backed off during his interview. Shearin went to see Brandi Mitchell, a prosecutor with the Dallas County district attorney’s office who was in charge of the Burnside case, and claimed that Thompson had perjured himself. What’s more, he said, Thompson had left out of the affidavit the fact that Burnside, who was right-handed, had been shot at point-blank range in his right temple, which would give a judge another reason to believe he had committed suicide.

All prosecutors know that almost every murder case contains inconsistent and sometimes contradictory evidence. Physical evidence can be more baffling than conclusive. Witnesses can shift their statements from one day to the next. Prosecutors are also aware that detectives can develop a kind of tunnel vision about a case. They can try too hard to make the existing evidence fit their theory as to who is guilty. As one Dallas County prosecutor put it, “They can, even for the most well-intentioned of reasons, get too focused on making an arrest at the detriment of the true story.”

Mitchell began evaluating Thompson’s case against Lord. She did her own interviews, speaking, for instance, with a firefighter who said he believed he had accidentally kicked the gun away from Burnside’s body. Mitchell realized that the evidence against Lord was weak, but she wasn’t prepared to say that Lord was innocent. “I wasn’t in the room when that young man got shot,” she would later say in an interview. “I can’t say unequivocally whether the young woman did or didn’t do the shooting because I wasn’t there.”

At the same time, Mitchell and other prosecutors in the DA’s office were not convinced Thompson had committed any serious wrongdoing. “For someone to say Dwayne maliciously would go after Miss Lord and try to set her up, I would say, ‘You have the wrong guy,’ ” said Andrea Handley, one of the office’s senior prosecutors. “Yes, the video of him interviewing her is pretty rough, and it looks like he comes across as a bully. But there was no corruption involved. If he had wanted to go after that girl, he could have made stuff up, trumped up reports, and hidden the Rastegar tape. Instead, he gave Brandi Mitchell everything he had.”

Mitchell eventually told Shearin that she was willing to dismiss the charges against Lord. But Lord wanted her arrest to be permanently removed from her record, which would require her to be “no-billed” by a grand jury, a finding in which the jurors refuse to indict a suspect, primarily for a lack of evidence. Nearly a year after the shooting, a grand jury met and heard the evidence. Shearin made his own presentation, about 25 minutes in length, laying out the case for his client’s innocence. When he finished, he left a packet of evidence that he’d compiled for the grand jurors to peruse, including the results of two polygraphs that concluded that Lord had not shown “deception” when she said she had not shot Burnside.

On May 11, 2011, in the case of Texas v. Lord, the grand jury returned a no bill. When Shearin called Lord with the news, she thanked him for all he had done for her, but then she said something else. “Who cares? Thompson has still destroyed my life and he’s still out there working cases. I want him held accountable. I want him brought down.”

Prior to her arrest, Lord had been known for her good-natured personality. She had loved dogs and painting. She had volunteered at an AIDS hospice. But after her arrest, Lord read The Count of Monte Cristo, the Alexandre Dumas novel about a wrongfully imprisoned man who seeks revenge against those responsible for his imprisonment, and she memorized one of the book’s famous lines: “May the god of vengeance now permit me to punish the wicked!” That was her goal, she said. She wanted to not only vindicate herself but also make sure the public knew just what Thompson had done to her.

Lord hired Don Tittle, a high-profile Dallas lawyer who specializes in civil rights litigation, to file a lawsuit against Thompson, which he did in late 2011. The lawsuit claimed that Thompson had violated Lord’s civil rights by engaging in “malicious prosecution”—in particular, that he had intentionally “misrepresented the facts” about Burnside’s shooting and omitted “significant exculpatory information” that would have proved Lord innocent of any wrongdoing. The lawsuit also claimed that Thompson had “permanently damaged” Lord’s reputation in Dallas and caused her to suffer “extreme emotional and mental anguish,” including “depression, insomnia, nightmares, and constant anxiety of the most extreme nature.” Lord was asking for monetary damages, and according to courthouse gossip, Tittle was not willing to settle for less than seven figures.

Burnside’s family and friends were caught off guard by the lawsuit. “It was so hard for us to believe that she was doing this,” said Jaffe. “I mean, she got no-billed. Okay, fine. Why wasn’t that enough? Why try to make money off Michael’s death?”

For her part, Lord said that she would gladly give up any money in return for Thompson’s being sent to prison. At the least, she said, she wanted to make sure his actions were “publicly documented” so that he could never do to someone else what he had done to her.

The trial finally began in a federal courtroom in downtown Dallas this past January—nearly four years after the shooting. Wearing a black dress and black heels, Lord came into the courtroom, followed by her friends and family. Dressed in one of his dark suits, Thompson strode toward his seat. Filing in behind him were at least a dozen of his fellow homicide detectives, there to show support. Lord glanced at Thompson and he glanced back. They had not laid eyes on each other since he had interrogated her. Then U.S. district judge Barbara Lynn gaveled the court to order.

In this trial, Lord was definitely the underdog. A police officer receives a high degree of protection when he conducts a criminal investigation. He can go so far as to lie to a suspect to try to obtain a confession. A citizen filing a lawsuit for false arrest must prove that the officer acted with malice, which is difficult to do. As Tatia Wilson, one of the City of Dallas attorneys representing Thompson, explained to the jury in her opening statement, “Sometimes homicide detectives may make mistakes in their evaluation of the evidence. They make honest, reasonable mistakes. But those mistakes do not amount to malice.”

Tittle, however, wasted no time going on the attack, telling the jury in his opening statement, “There is not and was not a shred of credible evidence to suggest that Olivia Lord had anything to do with Michael’s death. But Detective Thompson couldn’t or wouldn’t accept that.” Tittle said that Thompson “allowed a screenplay [of the shooting] in his mind to take over.” “And that’s a dangerous, dangerous thing if you’re a homicide detective with the Dallas Police Department.”

Lord took the stand and was overcome with emotion as she described her love for Burnside. She called Thompson’s interrogation of her “a mental rape” and characterized her days in jail as “torture.” Even now, she said, she felt like an outcast, afraid to go out in public. She had lost her career because potential employers, when running a background check on her, would always find a reference to her arrest for murder. She needed pills to go to sleep. “I’m still going to suffer for the rest of my life for this,” she said. Then she looked at Thompson. “I can’t undo what he’s done.”

When Thompson took the stand, he seemed utterly likable as he described his history as a detective. He calmly explained that his ferocious questioning of Lord after the shooting was nothing more than a technique used by detectives in police departments around the country—the “direct method,” he called it—in which a suspect is openly accused of a crime to see how he or she reacts. Thompson wanted to find out if Lord, under such heated questioning, would crack. And he knew she was hiding something, he said. He knew it. In fact, when Tittle asked Thompson, “Is it still your belief that Olivia Lord murdered Michael Burnside?” the detective didn’t hesitate.

“Yes, it is.”

“There hasn’t been one bit of evidence in this case that has caused you to pause in your opinion that she murdered Michael?”

“No, sir.”

For several seconds, the courtroom was quiet except for Lord’s muffled sobs. Then Tittle fired back. He asked Thompson if he had told one of Burnside’s friends that “this was the case of a lifetime”—the kind of case that could make him famous.

“No, that’s incorrect,” said Thompson.

“This has been kind of a sexy case here: an attractive female shoots the boyfriend, you solve the crime. That’s the exact type of case that might have been portrayed on The First 48, right?” Tittle asked.

“I don’t work cases for the sexiness of them,” Thompson snapped. “I work cases because that’s what I get paid to do.”

Tittle asked Thompson why he didn’t seem particularly disturbed that Burnside was drunk and had showed off his Beretta on the night of the shooting. “People drink all the time who own guns,” Thompson said. “That doesn’t mean they kill themselves.”

Tittle then asked about Rastegar. Thompson acknowledged that without the statement regarding Lord’s confession, “I wouldn’t have filed a case.” Tittle asked Thompson a series of questions about when he had actually written his arrest affidavit, which described Rastegar as making a “recorded interview” to the police about Lord’s “excited utterance.” Thompson was eventually forced to admit that he had typed up the affidavit before Rastegar had come down to the homicide offices to make his statement.

Thompson did his best to defend himself. He said that Lundberg had told him that Rastegar had “wavered a little bit” in his statement but that Lundberg had also let him know that “the gist was the same” and “nothing substantively” had changed from what he had already written in his affidavit. Lundberg also took the stand, testifying that he too remained convinced that Lord was guilty of murder. He insisted that what Rastegar told him in the homicide office “was the same and consistent with what he said out on the porch. Just because the words were less strong doesn’t mean they were any less true.”

Tittle next called to the stand a retired Dallas homicide detective named Kim Sanders, who said that Thompson’s interrogation of Lord was outlandish and that he left out key evidence in his arrest warrant. Tittle then had the jurors watch Thompson’s interview with Lord and Lundberg’s interview with Rastegar. He also had the medical examiner testify about what Thompson supposedly told him about the blood spatter on Lord’s clothes.

“I had to cover my mouth I was so appalled,” Judy Durbin, an accountant who was the foreman of the jury, would later recall. “There was no way a person with an IQ above 65 could have concluded that Olivia had shot Michael.”

Perhaps sensing that the jury had turned against the detective, Jason Schuette, another attorney for the City of Dallas, resorted to a surprise tactic in his final arguments. He told the jurors that he didn’t believe that Lord had shot Burnside. He actually turned to Lord and said, “I know you didn’t do it.” He turned back to the jury and continued, “But that’s not the issue in this trial. What this trial is about is whether this detective had probable cause to believe that she did it.” Then Schuette began listing all the reasons that would make a detective like Thompson believe Lord had killed her boyfriend.

The jurors, however, weren’t buying any of it. They returned a unanimous verdict in favor of Lord, and ultimately the city had to pay her $1.2 million, which reportedly was the largest judgement of its kind in Dallas. As Lord hugged Tittle and members of her family, Thompson stood at the defense table, his mouth open.

The day after the verdict, Thompson was placed on desk duty. One of his tasks was to take boxes of cold-case files out of the “death room,” where all homicide files are kept, and haul them to a storage area in city hall. In early May, word spread that the department’s Public Integrity Unit had launched an investigation of Thompson’s work on the Lord case. Most of Thompson’s fellow officers assumed it would be only a matter of time before he was fired—and perhaps even indicted.

But there was one more turn in the story to come. On July 15, the Public Integrity Unit’s report landed on the desk of Dallas police chief David Brown. The detectives in charge of the investigation had concluded that “there was no evidence to substantiate that Det. Thompson misrepresented any facts or falsified any government documents.” They also declared that there was “no evidence that Det. Thompson misrepresented any of the facts that were provided by Witness Rastegar” and that there were “no signs of a criminal offense.” Indeed, the report continued, Thompson “did have probable cause to arrest Suspect Lord.”

On August 6 Brown signed the report, and Thompson was cleared of any criminal wrongdoing. The case was then sent to the Internal Affairs division for an “administrative review.” If the review, which is ongoing as of press time, finds that Thompson violated departmental policies, he could be fired, suspended, or demoted. If the review determines that he did nothing wrong, he could be reinstated as a detective.

Although Thompson would not consent to my request for an interview, people who have talked to him say he feels that he has done nothing wrong. He remains convinced that he got a raw deal at the civil trial and that Tittle played the video of his interrogation of Lord only to plant in jurors’ minds the idea that he was an intimidating black man taking advantage of a grieving, attractive white woman. He was simply doing his job, he tells his friends, hunting for answers about a mysterious death. And even if he took a shortcut or two, he adds, he didn’t hide or invent evidence. He says he knows, without a shadow of a doubt, that he got the goods on Lord—and she not only avoided prosecution, she made a lot of money. “It’s insane,” he was overheard saying one afternoon at a restaurant near the police department. “I can’t say any more, but it’s insane.”

Lord, who is now 37 years old, still lives in the same apartment, and she has barely spent any of the money she won in her lawsuit. She works at a clothing shop, making $14 an hour, far less than what she was earning when she was in the mortgage business. She has also enrolled in college for the first time. (For a philosophy class, she wrote a paper on Socrates’ being sentenced to death under false charges.) After she graduates, she hopes to go to law school and perhaps someday work for the Innocence Project.

“I’m trying to figure out how to move on with my life,” she said recently, sitting at a back table at an Italian restaurant in North Dallas. She glanced around the dining room. “But I don’t know how to do it. It’s difficult to go out in public without thinking someone is saying, ‘There’s the girl who killed her boyfriend.’ ”

Right at that moment, a waiter walked up, clearly taken with her, and asked if she was ready to order. Lord could hardly look at him. “I did start dating a guy not long ago,” she said after the waiter left. “He eventually learned about my arrest, and he was so bothered by what he read that he never called me again. Thompson is the one who’s gotten away with the crime.”

Lord told me that she was not surprised to hear that the police department’s Public Integrity Unit had ignored the civil jury’s verdict and cleared Thompson. “What other results could you have with the police policing themselves?” she said. “You realize, don’t you, that if I didn’t have money from my family to fight back, I could have been wrongfully convicted, fighting this from prison. And what’s really frightening is that Thompson could come back after me, plant some new fake evidence, and arrest me for murder again. It’s terrifying.”

Lord’s claim of innocence has been bolstered by Rastegar, who told me that he never said to Thompson or Lundberg, not even on his front porch, that he had heard her confess to shooting Burnside. And a handful of Burnside’s friends have reunited with Lord, saying they now believe that she had nothing to do with his death. “I’ve talked to her many, many times, and if she is lying about what happened, she’s a hell of an actress,” said one friend, Eric Love. “Believe me, she adored Michael with all of her heart. The idea that she would put a gun to his head and pull the trigger is just unfathomable.”

But Love also acknowledges that he is “bewildered” at the idea of Burnside shooting himself. Burnside’s parents say that they still cannot believe that their son took his own life. “All we want is for Olivia to go through a criminal trial,” said John Burnside, sitting with Cindi in their East Dallas home. And then there’s Jaffe, Burnside’s best friend, who says he remains convinced that Lord is hiding something. Sipping coffee at a Starbucks one afternoon, he went through various scenarios of what he thinks could have taken place after he left Burnside’s home. Maybe, Jaffe speculated, when Burnside and Lord had started arguing, he had declared that he was never going to marry her, which sent Lord into a tailspin and led her to grab the gun. Or maybe in the midst of the argument, Burnside had pulled the Beretta out of the kitchen drawer for a second time, handed it to Lord, and said, in an effort to be dramatic, “If you hate me so much, then just shoot me.” And she did.

“Or maybe Mikey did it,” Jaffe said. “I know that he could get dramatic and a little crazy when he drank. And who knows? Maybe he got dramatic and put the gun to his own head and said to Olivia, ‘To hell with all this, I’m just going to end it now.’ And then, accidentally, he pulled the trigger. Or he mistakenly pulled the trigger thinking the Beretta was unloaded.”

Jaffe shook his head. “I’m willing to accept that it might have been an accident. I’m willing to accept that Mikey might have totally screwed up. But we at least have the right to know that. Seriously, does anyone believe this story that Olivia tells about being in the bathroom and hearing something that sounded like glass breaking in the kitchen? In that small house, she mistook the sound of a pistol shot for a glass falling to the floor? Come on.”

Lord closed her eyes when I asked her about those detractors who continue to believe she’s hiding something. “It’s so ridiculous. If I had killed Michael, then doesn’t it make sense that I would have walked away after I had gotten no-billed by the grand jury? If I was guilty, would I really have gone out and filed a lawsuit, knowing everything would be brought up again, giving Thompson and all the other naysayers one more chance to come after me?”

A few weeks later, I called Lord and asked her again about Burnside’s death. I wondered about the story Jaffe had told Thompson about finding her in the front yard, desperately saying, “I wasn’t going to leave him. I wasn’t going to leave him.”

She then told me something she had not mentioned before. After the argument was over, “Michael stopped being sarcastic and he became quiet and somber. He said that he couldn’t handle disappointing me on top of all the financial stress and tax problems that he was enduring.”

I asked Lord if she had said anything to Burnside that night that would have led him to believe that the relationship was over. Did she, in fact, tell him that she was leaving him?

“I wasn’t going to leave him,” she said, her voice breaking.

“But what did you actually tell Michael during the argument? Was it possible that he thought he was about to lose the woman he loved?”

Lord seemed to be trying to control her breathing. “I don’t want to answer that,” she said.

There was another, longer silence. And then she burst into tears. “I think Michael might have gotten the impression that I was going to leave him,” she said.

Five years later, Lord clearly remains tormented by that conversation, haunted by the idea that she might have said something that pushed her boyfriend into committing an impulsive act that no one could have imagined him doing. “Every day, dozens of times a day, I think about that talk and how I wish I could take it all back,” she told me. Thirty seconds passed as she wept before she added, “There are still nights when I drive by our home just to look at it. Sometimes I want to walk inside, thinking he will be there. But the man I loved is gone forever. Can you possibly understand how I feel?”