The caption on the front of the century-old postcard reads, “Gruesome scene, Juarez, Mex.,” and this is no lie: the image shows a dozen bodies laid flat on the scrubby desert floor in the shadow of at least fifty handmade wooden crosses. The message on the other side of the card? Bizarrely mundane. It reads, in its entirety, “Friend Edith, How is every thing Bob.”

Such peculiar juxtapositions are among the unpredictable payoffs of collecting old photos that were abandoned, for reasons unknown, by their owners. This postcard, picked up by artists Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey during thirty years of poking around the dark corners of junk shops, flea markets, and websites, is one of five thousand postcards, vintage snapshots, and other photo-oriented ephemera from their collection that have recently been purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. An installation including nearly sixty of their quirky finds, alongside portraits by legendary artists such as Andy Warhol and Diane Arbus, opens at the MFAH on November 21.

At a time when we’re swimming—or is it drowning?—in digital pictures, curators have realized that old “found” snapshots can be repurposed to tell the broader stories of our changing world. Levine and Ramey, who split their time between Houston and San Miguel de Allende, focused their collecting on a handful of themes—Mexico and the border, women, LGBTQ life, gun culture, and African American portraits, among others—that anticipated many of our current preoccupations. So why surrender the stockpile just as the culture is catching up to their interests? “These subjects matter to me personally,” Levine says. “But they touch all of our lives. Now feels like the right time to share the collection with a larger audience.”

Texas Monthly surveyed the collection and selected a few of our favorite images. Because found photos rarely come with detailed background information, we asked Lisa Volpe, the museum’s associate curator of photography, to provide a bit of CSI photo sleuthing.

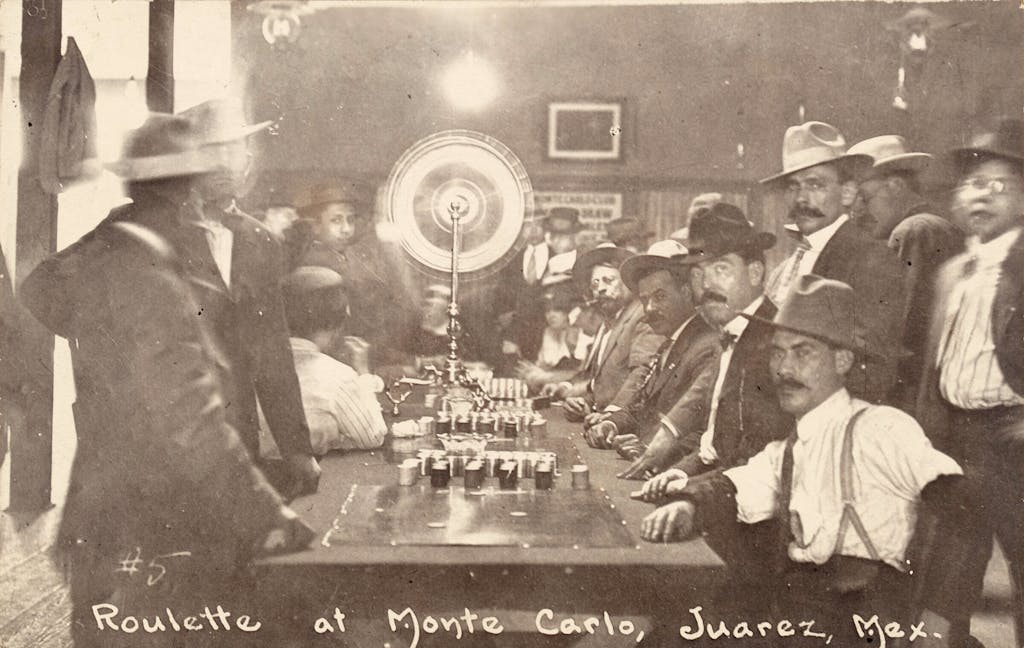

Roulette at Monte Carlo

During Prohibition, New Yorkers quenched their thirst by shimmying through unmarked doors and into clandestine speakeasies. Texans simply went to Juárez. “You could basically jump across the border for a few hours, get all your drinking done, and then go back home,” says Volpe. “There were actually shuttles from El Paso.” The Monte Carlo, pictured above during the Prohibition era, was, she says, “one of the three biggest gambling establishments in Juárez at the time.” If you look closely at this image, you’ll see, seated four mustaches down on the right, a man with glasses, a hat, and a big cigar. A striking resemblance to Teddy Roosevelt, you say? “There are a lot of theories about this,” says Volpe, who was instrumental in bringing the collection to the museum. “We do know Roosevelt was in Juárez at one point. And he’s kind of a man’s man, so it wouldn’t surprise me if he stopped in at the Monte Carlo.” At the same, she says, if it truly was Roosevelt, she believes the photographer would have capitalized on that in the caption in order to sell more postcards.

Women Smoking and Drinking Surrounded by Alligators

The half-dozen alligators might be first thing you notice in this studio picture, but they aren’t what make it interesting. In the early twentieth century, when this photo was taken, it was frowned upon for women to drink or light up in public. So these two, with their smokes and their bottles—not to mention that slight hike of the skirt—were leaning toward audacious. “These women were in control of this image and really wanted to present themselves as pushing the boundaries and fighting against the contained role of women at the time,” says Volpe. “Which is fantastic.”

Studio Cowboy

Back in the thirties and forties, when this picture was taken, you’d walk into a photographer’s studio and there would be a variety of costumes, props, and backdrops from which you could create your own scene. “The proprietors weren’t just selling you a photograph,” says Volpe. “They were selling you a fantasy.” Nothing concrete is known about this man or the studio in which the picture was taken. But there’s one deduction that can be made: the studio owner was probably Black, because at it’s unlikely that the “cowboy” would have been able to visit a white-owned photo studio.

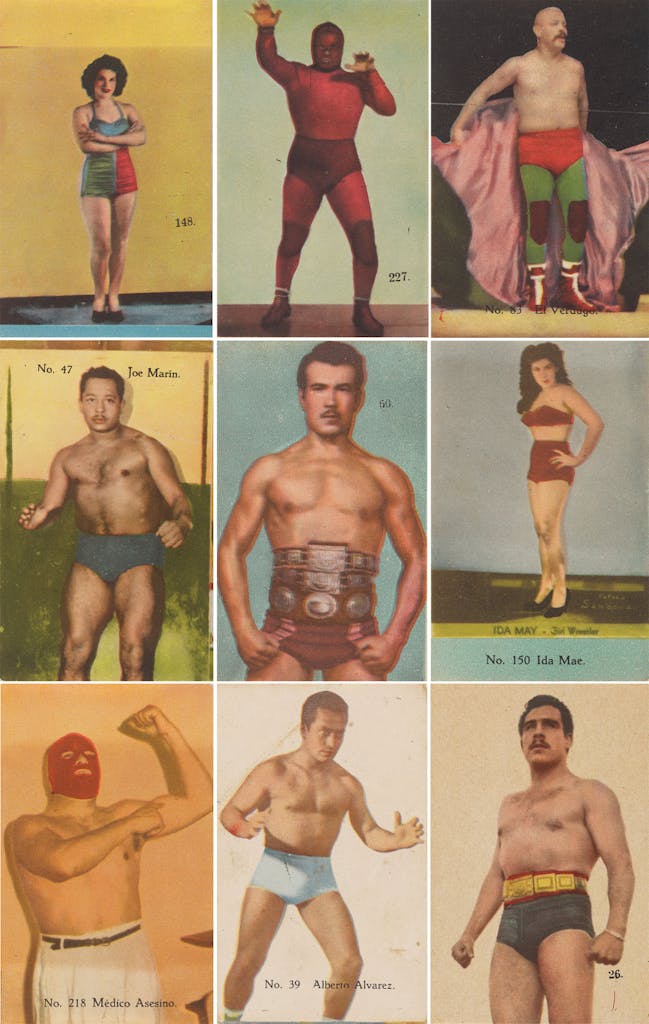

Luchador

Levine and Ramey’s collection isn’t composed only of photographs. It has photo-related objects as well, such as these luchador trading cards from the fifties. “Wrestling was on TV every Saturday night then, and these would have been very familiar figures at the time,” Volpe says. And the woman in the center? That’s Ida Mae Martinez. “She was an American who made a wrestling career in Mexico,” says Volpe. “So that’s kind of fun.” Indeed.

Birthday Dinner, 16 Years Old

If anyone was excited about celebrating this birthday dinner, it doesn’t appear to have been the birthday girl. And who was the young lady in this wonderfully (if accidentally) composed photo? Don’t know. Where was it taken? Los Angeles, apparently. (A quick Google search reveals that a restaurant called Armand’s was located in L.A. at that time.) For Volpe, the picture captures a cultural inflection point: “This is the moment that the category of ‘teenager’ is being coined.” In the postwar boom, kids this age had money and so became the focus of marketers’ attention: “This is the perfect representation of that because the girl is surrounded by all this commercialism, all these cars, all these billboards advertising various things.” The girl would be 82 today.

Walking Together

This is the kind of gem that people who love vernacular photography—people who skip Sunday brunch to hunt through dusty flea market bins—hope to find: a perfectly composed picture that holds within it mystery (why are these women carrying a suitcase uphill on a dirt road?), metaphor, and unspeakable tenderness.

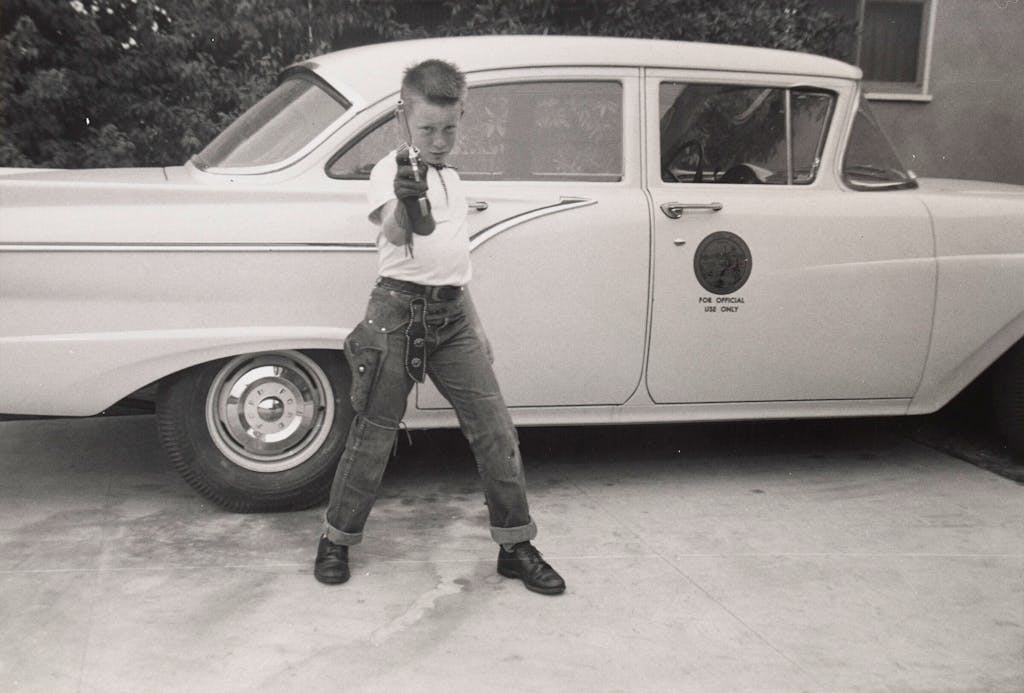

Boy With Pistol

You may not have stood in your driveway with your pants cuffed, holster hanging from your hips, silver six-shooter in your hand, but this photo still serves as a 3-by-5 time machine, conjuring those moments when, costumed and with childhood imagination cranked all the way up, you posed while Mom said “now keep still.” Such is the power of the “found” photo. (That said, this found photo is unable to explain why the car in the driveway carries an emblem that reads, in part, “for official use only.”)

Woman with Sunglasses Behind the Wheel

Often, the elements that we think ruin a picture—Uncle Louie both in the shadows and out of focus—are precisely what give a vernacular photograph its homespun charm. In fact, it’s not often you come across a found photo that plays like a professionally shot and styled movie-star image. Which is what makes this picture (with the cool shades, lipstick, and perfect over-the-shoulder glance) not only compelling but rare. The photo itself is undated but thanks to a careful examination of the steering wheel, Volpe knows that the car the woman’s driving is a 1940 Dodge.

Texas Mexico Border

What’s compelling about this picture is not the photo itself but the hand-drawn words—“Texas” and “Mexico”—on either side of the river. Without them, you’d have no idea what you were even looking at, which, oddly enough, is what makes this one of Volpe’s favorites in the collection. In her slightly photo-nerdy reading, the fact that you can’t see a border actually highlights the fact that, like all borders, it’s imaginary, a construct. At the same time, the photo itself isn’t doing its job because you have no idea what you’re looking at. (And, of course, we don’t even know if the captioning is accurate—it might not even be Texas!) As if to underscore that confusion, says Volpe, “There’s the guy standing there, almost like he’s trying to puzzle it out.” The picture dates from the 1910s or 1920s.

Two Men, One With Cigarette

When photo booths hit the scene in 1925, they were a revelation: for the first time, you could pose in absolute privacy, free from the judgmental eyes of the photographer, image developer, and kindly woman who handed you your pictures. When this picture was taken, in the late ’20s or early ’30s, the photo booth was still relatively new. The men are dressed identically with matching shirts, bow ties, and jackets. What to make of this? Like a visual detective, Volpe starts to assemble the clues: she first points to what looks like a saxophone neck strap hanging from the gent on the left. “I now think these guys are part of a band. And they’re in a photo booth, you know, so I’m thinking they’re performing in Atlantic City or someplace where you can see a band and have a photo booth, so probably a tourist destination,” she says. “None of this might be true, of course, but the story just starts exploding in my head once I see these small details.”

The installation opens at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, on November 21; for more info about Levine and Ramey’s projects, go to ProjectB.com.

Bill Shapiro, the former editor in chief of LIFE magazine, writes about photography.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- Houston