One Saturday night three years or so ago, I celebrated the impending nuptials of two friends at a dinner party in East Austin. Much wine was drunk, and, I’m relatively certain, at least one joint was passed in the backyard. Not bad, I thought, for a bunch of thirty- and forty-somethings. After dessert, the more resilient of us opted to take the party public. We grabbed beers for the four-block walk to a string of refashioned dive bars that had recently opened on East Sixth Street, an area we knew, not without affection, as Little Williamsburg.

Ten minutes later we arrived at the Liberty, which was the watering hole du jour for bewhiskered hipsters. Our bottles empty, we were looking for a trash can when suddenly a great, woolly bear of a doorman stepped from the shadows, snatched them from our hands, and gruffly informed us we were not coming in. That was fine. Street drinking is illegal in parts of Central Austin, particularly in front of bars. We acknowledged our transgression and readied to move on. But then a furious kid in a hoodie popped up and informed us we’d committed a far greater crime. “Hey, yuppies, why don’t you get in your BMW and drive back to Pflugerville!”

“Excuse me?” I said. (Full disclosure: I may have been wearing a blazer.)

“We rode our bikes here!” he spat. “We’re from the neighborhood.”

“From the neighborhood?” I asked. “As in, you came up on the hard streets of East Austin? You used to hang here when this was a string of Tejano bars? Because I don’t remember seeing you twenty years ago when I used to come hear conjunto bands at La India Bonita.” Actually I didn’t say any of that. I was too busy keeping a buddy from dropping the kid in a dumpster.

Once order was restored, we repaired to the Brixton, another new place with a friendlier beard-to-blazer ratio, meaning it was a quarter the size of the Liberty and I knew a bartender. Nursing a Lone Star, I wondered if this was my Lost Austin Moment, the instant I’d realize the city I knew and loved was no more. But it occurred to me that my hood-rat adversary might be mulling the same question over a Brooklyn Lager at the Liberty. We couldn’t both be right. But what if both of us were wrong?

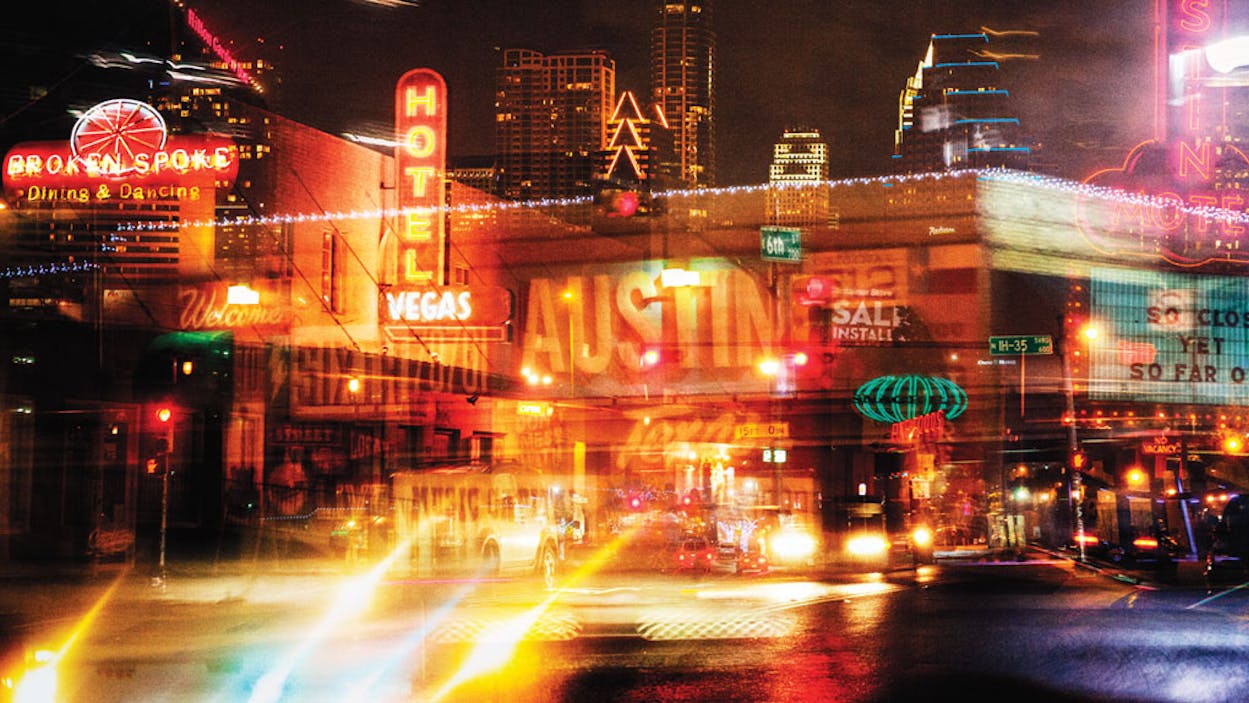

Everybody’s got a gripe with Austin, and it typically revolves around growth. Traffic’s a nightmare. The cost of living is too high, driven up by newcomers who don’t share our values. Annual events like ACL Fest, Formula 1, and the ever-expanding South by Southwest have turned us into a high-rolling tourist town with an unseemly yen for celebrity culture. The sea changes to downtown portended by plans for a new multibillion-dollar medical school and a multimillion-dollar reimagining of the pathway and parks along Waller Creek don’t make sense in the small town that Austin once was and should rightly still be. The list goes on but always winds up in the same place: Austin quit being Austin when some favorite haunt of the complainant either (a) closed down, (b) moved to cleaner, roomier confines, or (c) was overrun by people the complainant didn’t know.

All you ever learn from such criticisms is the general time frame in which the critics came of age. If they miss the punk-rock stages at Emo’s, they’re from the nineties; if it’s Liberty Lunch’s open-air, college-rock eclecticism, they’re from the eighties; and if it’s the Armadillo’s cosmic cowboy mélange, they’re from the seventies. They’re like people who only listen to the music they loved in college. Their deeper beef is with their own fading relevance, their loosening grip on the handle of cool. And if you are one of them, if you sincerely believe that Austin was better when the only place to get a steak was the Hoffbrau—which, by the way, is still serving—then there’s a ribeye at Lamberts you should try.

The Armadillo didn’t create Austin any more than Emo’s did. It was, in fact, the other way around, and the forces at work are considerably older than the fashion statement made by wearing cowboy boots with cutoffs. There was the natural beauty that prompted Mirabeau B. Lamar to put the capital here when Texas was still a republic, in 1839. The landscape lent itself to retail and white-collar commerce rather than large-scale farming, attracting a free-thinking citizenry that would make Austin one of the state’s few areas of opposition to secession in 1861. The University of Texas, established in 1883, created a constant flow of youth, and the combination of the school’s faculty and staff with thousands of state employees at the nearby Capitol complex ensured a steady supply of jobs and a reliable economy. Those three widely cited factors—scenery, students, and state jobs—bred a fourth constant that nobody ever bothers to remember: growth. Austin’s population has grown at virtually the same rate for seventeen straight decades. And at any given moment in history, somebody was bellyaching about how much better Austin was before all these damn people got here. The Austin that people fret over now is of a fairly recent vintage, created by three key twentieth-century imports: dams, guitars, and microchips. The perception of Austin as an outdoor-rec mecca was encouraged by the chamber of commerce in the fifties and sixties after the construction of seven dams on the Colorado River created the Highland Lakes. Back then the emphasis was on motorboats and water skis, and our nickname was the Funtier Capital of Texas. The city’s jogging and bicycling cultures grew from that push, and now Austin brags of being regularly listed among the nation’s fittest cities. Austin first gained acclaim as a music town after Willie Nelson moved here in 1972, and it went on to produce rock stars as varied as Stevie Ray Vaughan and Spoon. And we started moving toward technopolis status when the computer R&D consortium MCC announced it was coming to town, in 1983. The ensuing tech boom finally brought fine dining and meaningful philanthropy to town.

To be sure, growth has affected the Austin ideal. Driving downtown is impossible most weekends because of all the fun-run road closures. Seemingly every restaurant features an off-key singer-songwriter. The techie invasion drove housing costs through the roof. But with nimble navigation, none of those problems is unmanageable, not even the housing. Though Austin went from being Texas’s most affordable city for housing in 1990 to its most expensive in 2000, my own rent dropped during that same period from $150 a month to $0. (And note: at no time did I move in with my parents, though I did have to do chores for my landlords and endure a lot of Kato Kaelin jokes.)

None of those aspects of Austin life are in danger of extinction. “We are growing because of the attractiveness of the city,” says Will Wynn, Austin’s mayor from 2003 to 2009. “The Census Bureau just found that more 25- to 34-year-olds are moving here than anywhere else in the U.S. It used to be that to draw people you had to build huge pieces of economic infrastructure to draw jobs first. But in today’s world, jobs follow people, particularly younger, educated, creative people. And that’s who’s moving to Austin, because they like what’s here. They’re not moving here to make it more like Ohio or Michigan.”

The bigger problem may be that the new kids don’t just like it—they love it. I’ve occasionally complained about the evolution of Austin City Limits, the live-music TV show born of the music scene in 1975. When I was at UT in the late eighties, the performers were typically country acts, and I could get tickets to every taping. But at some point, ACL repurposed itself and now features the biggest recording artists in the world. Do I really think that the Moe Bandy–Gene Watson double bill I saw in 1988 was better than the Radiohead episode taped last year? No. My problem with the Radiohead show is that I couldn’t get in. Neither the show nor the city is a secret anymore.

A frequently heard defense of the changes in Austin is that the city is growing up, and there are those who argue that “growing up” means growing out of the quality that made Austin Austin. They’ll tell you that real Austin was a place where you could wear shorts and a T-shirt into any restaurant in town, no matter the hour. For my part, I’m thankful to the old girlfriend who instructed me that grown men don’t wear short pants in public after dark. I’m also grateful for the city leaders who, in the mid-nineties, got the maturation ball rolling.

A little history may help. When the tech boom took off, Austin’s public life was defined by the Development Wars, a ferocious conflict between developers planning subdivisions for transplants from Silicon Valley and environmentalists fighting to protect the Edwards Aquifer. Neither faction showed the other anything but contempt, depicting each other, respectively, as profiteering land-rapists and communist tree-huggers. But in 1997, Mayor Kirk Watson, now Austin’s state senator, ended the battles with a highly evolved recharacterization. He started talking up the city’s natural beauty as one of the primary reasons companies wanted to move here. He described protecting the environment as a financial concern, not a moral imperative. Suddenly the lions and lambs shared a common goal. The city began to encourage development in a then-empty downtown and pushed bond ordinances to buy environmentally sensitive acreage in the aquifer’s recharge zone. Today, while downtown booms, 60,000 outlying acres have been purchased and protected, and our sacred public swimming pool, Barton Springs—which spent the nineties silted up from subdivision runoff—is crystal clear, just as in the glorious seventies.

Another example: “Keep Austin Weird.” The rest of the state likes to mock the slogan as more ill-placed Austin smugness (never mind the irony of Texas viewing Austin in much the same way the rest of the country views Texas). But the fact is that “Keep Austin Weird” was a savvy grassroots campaign that is now keeping millions of dollars in the Austin economy.

In mid-2002 a developer armed with $2.2 million in incentives from the city planned to put a Borders Books and Music store near Sixth and Lamar, barely spitting distance from two Austin institutions, Waterloo Records and BookPeople. The local shops fought back, not in protest of oncoming competition but against the idea that a national chain would receive incentives that locals don’t. They adopted “Keep Austin Weird” as their battle cry, putting it on bumper stickers and in the subject lines of a massive email blitz on city hall. But they also opened their books for a study contrasting the economic impacts of national chains and local businesses. The study, which the local businesses commissioned along with several Austin activists who, in an earlier era, might have tried to stop bulldozers by chaining themselves to trees, found that for every $100 spent in a national retailer, $13 stayed in the local economy. But that same $100 spent in a local, independent business would keep $45 here. The protesters stressed the economic argument. And though Borders’ decision to give up on downtown Austin in early 2003 may have owed as much to the national economy as anything, both the city and developers took note.

Half a mile away, the Second Street District was beginning to take shape and was already being derided as Dallasification. Tall, shiny buildings will inspire such slander. But when developers started looking to fill street-level retail space, the city pushed them to include 30 percent local businesses; the project managers ended up more than doubling that. So while the district includes chain restaurants like Cantina Laredo and III Forks, they are far outnumbered by homegrown success stories. The Royal Blue Grocery, a one-stop corner store started by two dudes who used to wait tables at Chuy’s, has added two more locations downtown. The Violet Crown Cinema, situated somewhat awkwardly above a tapas bar, is believed to be the number one movie theater in the country in terms of dollars generated per seat. And the district’s endlessly informal, unofficial hub is Jo’s, a coffeehouse and restaurant that the owner, Austin hotelier Liz Lambert, named after her mother.

Lambert exemplifies the blurred line between old and new Austin. She grew up in Odessa before coming to UT in the eighties and then, after four postgrad years in New York, moved permanently to South Austin in 1994. At the time, South Congress Avenue was relatively deserted, its commerce split fairly evenly between a fifties-era holdover nightclub, the Continental Club; the gun shop next door; and hookers in the parking lot of a dirty-movie theater eight blocks south. Lambert bought an hourly-rate motel across from the Continental, the Hotel San José, then tricked it out and reopened it in 2000, introducing Austin to the concept of hip hotels.

Over the next decade, the South Congress strip filled with retailers and eateries, becoming one of Austin’s primary destinations for citizens and tourists alike. There’s a gripe to be made about the crowds on the weekends: forget finding a parking space—it can be hard to find room to move on the sidewalk. Yet all but two of those businesses are local, and old-Austin priorities reign. Home Slice Pizza co-owner Jen Strickland, who developed her recipes and business plan with her husband and a college friend while bouncing between web jobs in the early aughts, has rejected numerous pitches for new locations and franchising, saying simply, “We don’t want to dilute our vibe.” Lambert tells a similar story. “I own the San José’s parking lot, where the original Jo’s coffee stand is,” says Lambert, “and people have said I should develop it. But it brings a value to the hotel and the neighborhood. We hold benefits there, free SXSW parties, our Easter pet parade. If all I wanted to do was make a profit, that’d be five stories of hotel rooms.”

She’s neither ignorant nor immune to the need to make a buck. But just like her customers who used to walk past a Starbucks—now closed—to pay a little extra for coffee at Jo’s, she feels a loyalty to the town. By some traditional measures (racial diversity in particular), Austin may not be as progressive as it projects, but it has always allowed people to be themselves. It doesn’t just tolerate otherness, it celebrates it. In the Austin mythology, struggling country singers become Willie Nelson; nerdy college dropouts become Michael Dell; and bored party-girl homemakers become Ann Richards. The people here appreciate that quality and want to protect it.

That’s the emotional core to keeping Austin weird, and it persists, even in the districts that seem to have the least to do with what used to be here. Among the slick, million-dollar, high-concept bars on Rainey Street, you can find the best Indian food in town at G’Raj Mahal, a food truck parked in a vacant lot. Amid the trend chasers slumming on East Sixth—and just around the corner from the Liberty—you can two-step with a sixty-year-old at the ramshackle White Horse honky-tonk, where every Sunday afternoon there’s a neighborhood potluck with live conjunto accompaniment. Or walk one block from there to the Yellow Jacket Social Club to discuss classic literature and skateboarding history with Stan the bartender and co-owner. Ask him about how he and some friends built the beer garden out of salvaged pieces of old skate ramps or about his intermittent stints as a roadie for the Riverboat Gamblers punk band. But don’t forget to grat him; though he and his wife, Mimi, finally paid off their investor, they’re still living out of the tip jar.

That’s not old Austin or new Austin. That’s just Austin.