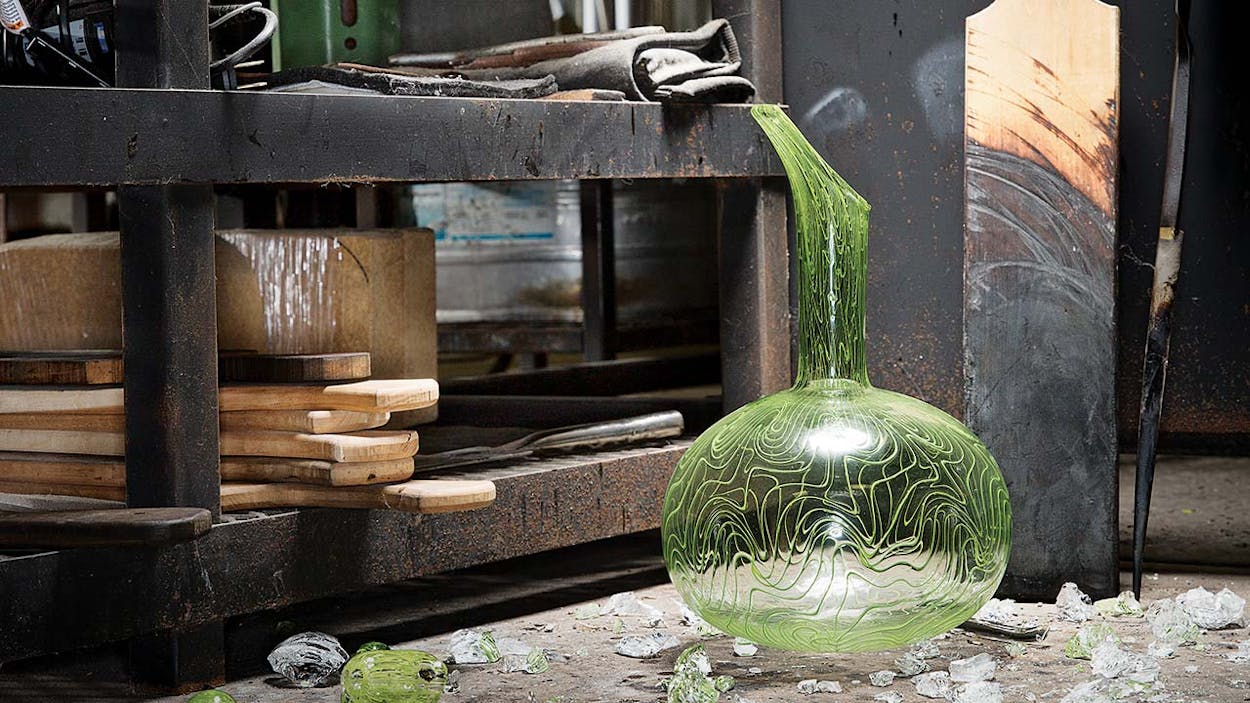

The furnace in Brad Pearce’s downtown workshop is blazing at 2,100 degrees, the perfect temperature for working glass. Fortunately there’s a breeze coming off Corpus Christi Bay, three blocks away. Freda, the shop cat, looks on as Pearce rotates a five-foot-long steel rod in the fire to gather molten glass. Then he walks the rod to a steel table—a marver, in glassblowing speak—and begins to roll the hot glass back and forth on the tabletop. Every so often Pearce blows into the end of the rod until a brilliant red vase emerges. The vase is part of his Marea (Italian for “tide”) collection, which includes not only vessels but boldly colored light fixtures, stemware, and tableware with a pattern of undulating lines embedded in the glass. He’s been honing this signature look for nearly fifteen years, ever since a broken foot in high school turned his attention away from football and toward art. He enrolled in a studio art class and, after watching a TV segment on glassblowing, was inspired to visit the Rockport studio of Steve Russell. “He gave me the full tour and asked if I wanted to attempt to gather some glass from his furnace,” Pearce recalled. “I was seventeen, and it was surreal, because in that moment, I discovered what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.” After high school, Pearce worked at the Taos Institute for Glass Arts, in New Mexico, before heading to the Cleveland Institute of Art, where he majored in glass and minored in ceramics. Upon graduating, he was a teaching assistant everywhere from Washington to Maine to North Carolina. But when he started his own business, in 2015, there was no question in his mind that he wanted it to be in his waterfront hometown of Corpus Christi.

Q&A With Brad Pearce

What drew you back to Corpus?

I love the relaxed island vibe within the confines of a big city. Corpus is filled with all types of people and cultures, but no matter how much it grows, it always feels tight-knit.

What about your visit to that studio in Rockport made you want to pursue glassblowing as a career?

The intense heat. When Steve opened that furnace door, it was as if he had opened the gates to hell. I immediately knew this was a serious medium that demanded the utmost respect and focus, and I was attracted to that. At seventeen I had never met anyone like him, a man making a living with his hands totally on his own terms. No boss, no rules, no limitations. I also liked that the process required teamwork. I knew that this craft had the potential to fulfill all the things I was missing about sports.

Do you always work with someone else?

Some people work alone, but anytime I have the furnace going, I always have a partner. The heat is dangerous. The studio can be 130 degrees in the summer. And while it’s difficult to find someone capable, when you do, the process is a magic dance that requires little to no verbal communication.

You built your shop out over a year. What are the most important tools of your trade?

The heart of the operation is the furnace, but each part of the shop is vital. The glory hole is a secondary furnace where we can keep the glass at a steady temperature in order to manipulate the shape. Without the glory hole, the molten glass would cool and harden and become unworkable within minutes. There is a garage, which is essentially an oven that keeps parts that we have made at an ambient temperature—roughly 1,000 degrees—until we are ready to incorporate them into the work. And the last major piece of equipment is an annealing oven. This allows us to slowly cool a glass piece from working temperature to room temperature over ten to twelve hours. Without annealing, the glass simply cannot withstand the dramatic temperature change.

How long does it take to make a vase?

That varies based on size, difficulty, and pattern. A series of several similarly styled works made at the same time could take several days. But whenever I’m asked this, I generally respond with “fifteen years, two days, and two hours.” Cheeky, but true.

For more information, go to bradpearceglass.com.

- More About:

- Art

- Corpus Christi