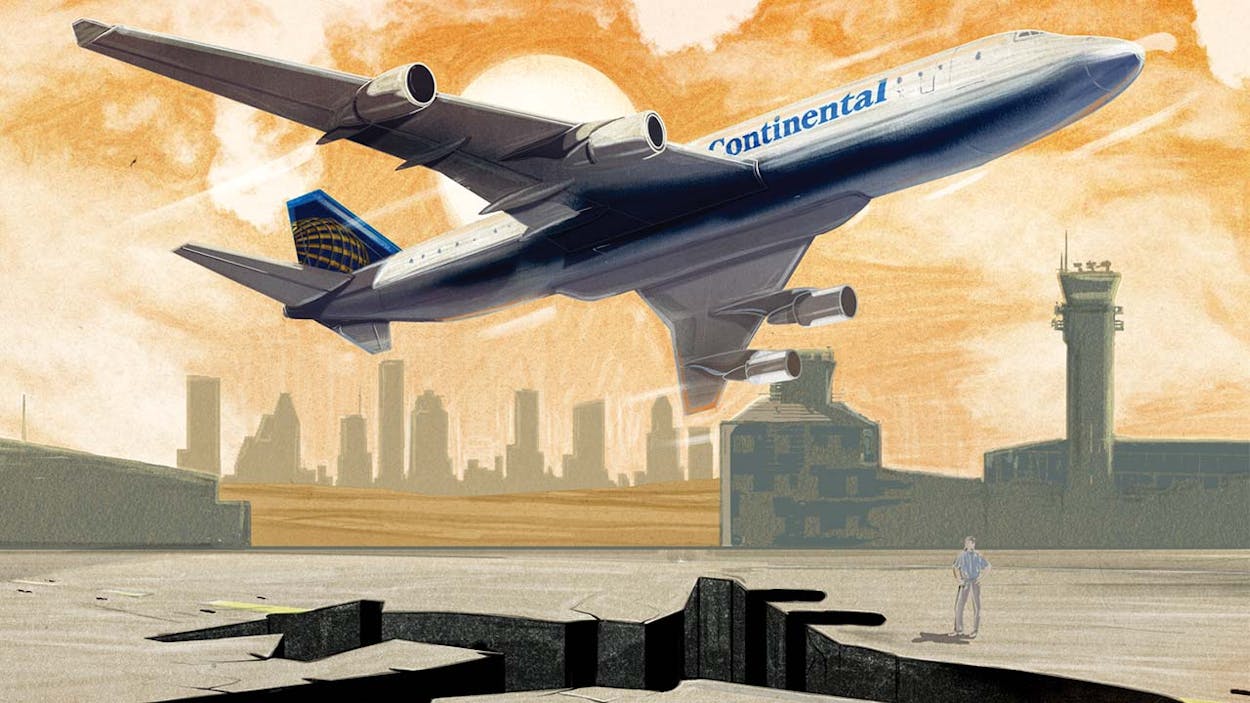

As news of United Airlines CEO Jeff Smisek’s departure reached Houston in early September, you could almost feel the collective response: good riddance. Even before Smisek was caught up in the corruption investigation that led to his resignation, many Houstonians resented him for merging their hometown airline, Continental, with the Chicago-based United five years ago. The move cost Houstonians more than first-rate air service—it stole a bit of civic pride. Just months after NASA ended the space shuttle program, Houston lost its only airline; Space City was grounded. “Continental had Houston DNA,” says Jeff Moseley, the former head of the Greater Houston Partnership. “To see it fold up and move out of town was painful.”

What hurt the most, perhaps, was that Continental was a paradigm of the sort of corporate innovation that Houston has long prided itself on. “Continental’s whole history was being a maverick airline,” says Phil Bakes, the company’s president in the mid-eighties. And much of that history was tossed out the window after it was swallowed up by United. “When the merger was announced, I went, ‘Uh-oh,’” says Huntsville businessman Rich Heiland, who flew about 100,000 miles a year on Continental. As a management consultant, Heiland knew that the biggest hurdle for the two companies wouldn’t be integrating systems, processes, or technology but reconciling their cultures. “When it was announced that the headquarters would be in Chicago, I felt the war was lost.” He still flies regularly on United—he really has no choice, as the airline accounts for the vast majority of flights out of George Bush Intercontinental Airport—but he says the quality of the service has declined markedly.

Continental’s maverick character was baked into the company three decades ago. The airline arrived in Houston from Los Angeles in 1983 following a hostile takeover by Frank Lorenzo’s Texas Air. The Carter administration had deregulated the airline industry in 1978, and carriers were still figuring out how to thrive in a market in which the government no longer controlled prices or routes. Lorenzo realized that competing on price meant Continental needed to lower its costs. The biggest expense was labor, so he asked his pilots to cut their pay in half. They refused and vowed to strike.

On September 24, 1983, Continental filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which Lorenzo claimed allowed him to void the union contracts. The pilots took him to court, touching off a two-year legal battle. In the end, the hardball tactics worked, wages were cut, and Lorenzo became the most hated man in the airline business.

While his methods were harsh, they were influential; many of the big carriers went on to use bankruptcy to restructure their costs. “That bankruptcy in many respects was part of the legacy of innovation,” Bakes says.

After the labor acrimony ended, Bakes, who became the airline’s president in 1984, began rebuilding Continental’s culture. He aligned employee incentives with the carrier’s goals. To save on fuel costs, he gave bonuses to pilots who used less fuel. In 1985 he developed “the airport of the future,” a plan to introduce ticketless check-in, self-serve baggage checks, and other ideas that employed computer technology to cut costs and increase convenience. But Lorenzo, who had been buying up airlines for most of the decade, never implemented Bakes’s plan and sent him to Miami to run the newly acquired Eastern Air Lines. (Eastern was liquidated a few years later.)

Despite these changes, by 1987 Texas Air was staggering under the debt amassed from its takeovers, and Lorenzo executed a massive merger of many of the company’s holdings. People Express, Frontier Airlines, New York Air, and several commuter operations were folded into Continental. Among other things, Continental inherited People Express’s Newark base, which is at the center of the current scandal that brought Smisek down. (The feds are trying to determine whether United did favors for a government official in order to get improvements made to Newark’s airport, a major hub for the airline.)

Texas Air, renamed Continental Airlines Holdings, remained burdened by debt, and in 1990 Lorenzo agreed to sell his stake to the Scandinavian Airline System. The sale came with a key condition: Lorenzo had to go. “Without that in the picture, we wouldn’t have done it,” SAS chief executive Jan Carlzon said at the time.

With little choice in the matter, Lorenzo departed as CEO (though he remained on the board for two more years). But Continental’s problems continued. Soaring oil prices and debt pushed the carrier into bankruptcy once again. The first era of Continental’s innovation ended with a whimper.

But Continental’s second wave of innovation was about to begin, led by a CEO who was in many ways the anti-Lorenzo. Investor David Bonderman, a protégé of Fort Worth’s billionaire Bass brothers, orchestrated a $450 million buyout of Continental in 1992 and hired pilot and former Boeing executive Gordon Bethune to lead the turnaround. Greg Brenneman, a former Bain & Company consultant whom Bethune hired as chief operating officer, later recalled that the company’s planes were old, dirty, frequently late, and notable for interiors that often had multiple color schemes. Thanks to Lorenzo’s 1987 mega-merger, Continental was an amalgam of half a dozen different airlines. “When a seat needed to be replaced, the company used whatever was in stock,” Brenneman said in a 1998 Harvard Business Review article.

The U.S. Department of Transportation ranks airlines by four key benchmarks: on-time arrivals, lost baggage, customer complaints, and “involuntary denied boardings.” Continental ranked worst in all four categories. The company hadn’t posted a profit outside of bankruptcy since deregulation, in 1978.

To improve customer service, Bethune and Brenneman knew that first they had to boost employee morale. Lorenzo’s gutter reputation stemmed from not just what he did but how he did it. He came across as uncaring and aloof even as he implemented changes that upended employees’ lives. Bethune, on the other hand, acted like one of the guys. A blunt-spoken Austin native, he liked to fly in the cockpit’s jump seat and chat up the pilots. Brenneman may have looked like a nerdy numbers guy, but workers quickly came to trust him. “They made the employees very much a part of making Continental a better airline,” says Bill Swelbar, the executive vice president of InterVistas Consulting, a firm that specializes in transportation. “Bethune had a personality that was larger than life, and people just gravitated to the guy.”

The company introduced a new exterior color scheme—the white fuselage with a blue tail and the globe logo that United still uses—and updated the patchwork interiors. Brenneman also eliminated Bakes’s fuel-saving plan. Though the program had decreased fuel costs, it undermined customer service. Pilots would turn off the air-conditioning when the plane was on the ground and fly more slowly. They used less fuel, but passengers arrived sweaty, late, and miserable, and ground personnel had to work overtime to accommodate missed connections.

Bethune and Brenneman combined the feel-good aspects of their turnaround with careful scrutiny of costs and created incentives that, this time, aligned employees’ interests with those of passengers. Instead of offering a bonus for fuel savings, they rewarded every employee with a $65 check every month that the carrier finished in the top five airlines for on-time performance. They implemented a profit-sharing plan for employees and actually made a profit: $556 million in 1996. The stock price rose from $3.25 to $50 a share. And those DOT benchmarks? Continental was now third or fourth in every category. The turnaround was so impressive that ailing companies such as US Airways and even Burger King and Quiznos started poaching Continental’s management talent.

Larry Kellner, a soft-spoken former banker, took over after Bethune retired, in 2004, and he maintained Continental’s focus on customer service. For the most part, employees liked working at Continental and passengers liked flying the airline. But after the financial crisis in 2008 and the merger of Delta and Northwest, which made for a daunting competitor, Wall Street wanted more mergers, arguing that there were still too many empty seats on too many planes. Investors and even some board members wanted Continental to merge with United, but Kellner resisted, fearing that United’s long history of labor strife would overwhelm any growth prospects.

Kellner departed in late 2009 and was succeeded by Smisek, who had joined Continental in 1995 as general counsel from the Houston law firm Vinson & Elkins and had been an important part of the turnaround team. Smisek took a more analytical view of the merger. He saw Continental losing market share on key routes if something wasn’t done. “We’re very comfortable that this improves our competitive position,” he told me at the time. Delta was by then the biggest airline in terms of revenue, United was holding on to second place, and US Airways was sniffing out a merger with number three, American. Smisek feared Continental would be left a distant fourth.

And so, in 2010, Smisek struck a deal. Though he called it a merger, he basically sold Continental to United; the name “Continental” disappeared and the Houston headquarters was essentially vacated. Continental’s management team was supposed to be in charge, but it never took root in the cold climes of Chicago. “The Continental culture was a terrible thing to risk,” Bakes says. “United’s history is one of bureaucracy and arrogance, and it ended up culturally being more dominant.”

The airline became the biggest in the country—and then slipped to second when American and US Airways merged in 2013—but it bears little resemblance to the company that Bethune and Brenneman built. Since the merger, United has struggled with flight delays and languishing labor agreements, and it sits in the basement of the DOT rankings. (In late September, Smisek’s replacement, Oscar Munoz, began making unusually candid public comments about the airline’s shortcomings.) Not all of those problems can be laid at United’s doorstep. Smisek lacked both Kellner’s affable nature and Bethune’s charisma. Heiland, the United frequent flier, recalls years ago seeing Southwest’s legendary co-founder, Herb Kelleher, in the terminal at Dallas’s Love Field. He worked the room, chatting up passengers before boarding. Recently, Heiland saw Smisek and a friend waiting for a flight in Chicago. “They stood there for probably twenty minutes, talking to each other,” Heiland says. “He never greeted or acknowledged a customer.”

It’s easy, and misleading, to romanticize Continental’s glory days. Even during the height of Bethune’s tenure, it was outgunned in most major markets by larger airlines, and during the Kellner era it lost money more often than not. It was an airline, after all. But it also had a history of trying to change what we hate about airlines. Smisek’s ouster brings that era to a close, but for many Houstonians, it was already over. It ended the day Continental left town.