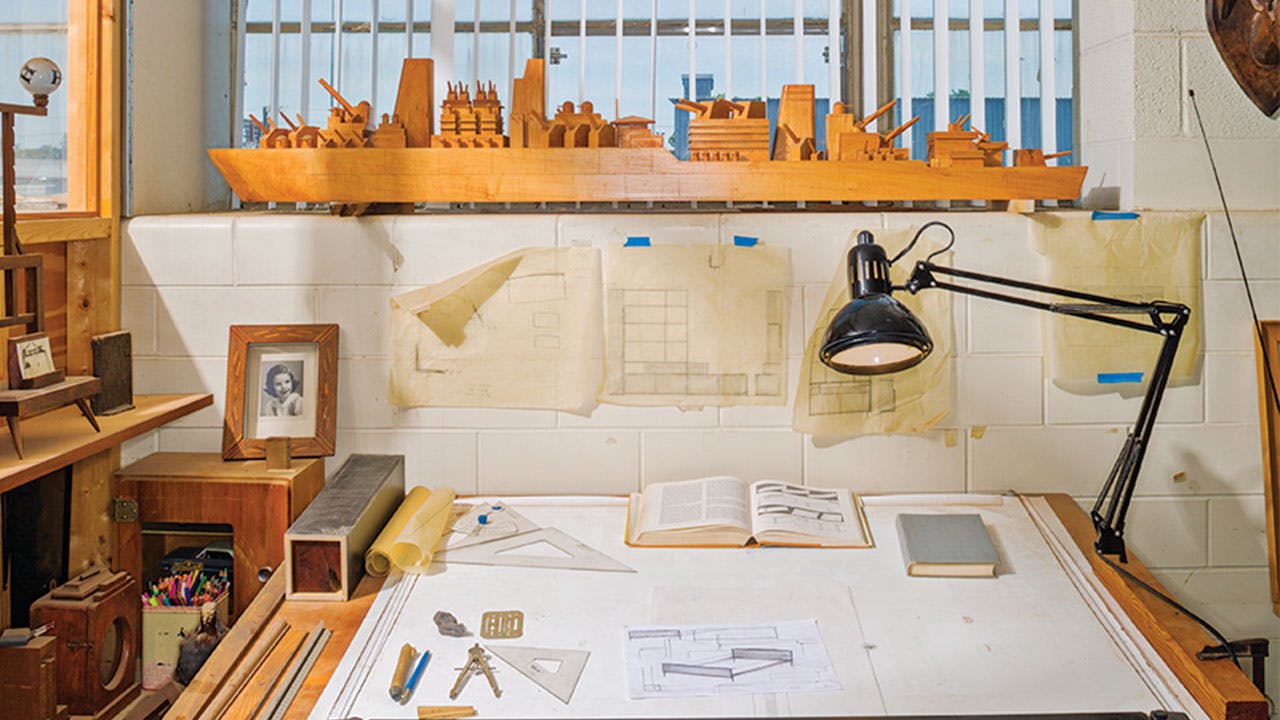

Dan Phillips hunches over a worn-in drafting table in the middle of his East Dallas studio, which occupies the second floor of the twenties-era warehouse that was once the Ford Motor Company assembly plant. Model T’s used to come off the line here (each of which went out the door with a “Built in Texas by Texans” decal on its back window), and the industrial space seems well suited to Phillips, who is in many ways a throwback to an earlier time. The son of an architect and an artist, Phillips grew up in Dallas, and in 2005, when he was 28, he enrolled in the cabinet- and furniture-making program at Boston’s North Bennet Street School, a renowned craft and trade school. Making furniture has been his full-time job ever since he graduated and returned home, though the 39-year-old father of two also paints (he shows at the Webb Gallery, in Waxahachie) and sings and plays guitar for the Dallas band True Widow. He always sketches with a pencil and a straight edge, likes to walk to work, and considers a computer to be a “necessary evil.” As he draws a chair for his bespoke furniture line, D. H. Phillips, one of the colorful tattoos that cover most of his body peeks out from his plaid work shirt.

Phillips’s handmade pieces—everything from mahogany bar stools to walnut chairs with channeled leather—are sleek and have the clean lines of mid-century design, but his work is rooted in traditional furniture-making techniques. He favors classical proportions and eighteenth-century details like inlays, beading, and molding, and his desks, pencil-post beds, and jewelry boxes are influenced by motifs ranging from the crude to the sophisticated. “I love a naive six-board chest as much as I love a Federal period secretary,” Phillips says. He often makes his commissioned pieces using hundred-year-old tools, and his workbench is lined with dovetail saws, chisels, hand planes, and other old-school implements. “I like making my pieces with the old stuff that guys before me used,” he says. “I hope someone will take all my tools and use them when I am gone to keep making stuff.”

Q&A With Dan Phillips

You have a fascination with the old, but your work feels modern. How do you achieve that balance?

I use the same finishes that are on most antiques, like shellac and waxes. I aim for my work to be timeless and to not follow any trends, although my pieces may have been trendy back in 1785.

Do you name each piece of furniture that you design?

Some people name furniture after the first client who ordered it. The last name of the first person who ordered a chair from me was Gross, which didn’t work as the name of a chair for obvious reasons, so I just call it the Lounge Chair. I never officially name pieces, and I try not to make the same thing twice.

If you could collaborate with any maker, living or dead, who would it be and why?

Oh, man, too many: Edward Barnsley, because he was so tasteful in his use of classical details and his work was a perfect blend of period and modern design; John and Thomas Seymour, because they were the masters of their time; Wharton Esherick, because every piece of his is like a sculpture; and Duncan Phyfe, who made lots of beautiful things. My favorite pieces of his have lots of moving parts and secret drawers and tricky business.

What is your process like when someone commissions you to make a piece?

Generally I’ll go out to the site where the furniture will live and talk with the folks about what they want. Then I’ll do some drawings and invite the client over to the shop to look at the designs and see the shop and get a feel for my process. Once the design is settled on, I will do the real drafting to figure out all the difficult things. Then I’ll get the wood, break it down into parts, put those all together, and finally get the finish on. I always snap some bad pictures on my phone before I deliver the piece.

How do you price your pieces?

Chairs range from $2,500 to $3,000 and tables between $3,000 and $4,000. It depends on what it is. I figure out how much time it will take to make a piece, then I calculate my day rate plus materials. I try to have the least amount of money go through my hands. I place no esoteric value on anything. Materials cost what they cost. I don’t inflate anywhere.

You and Dallas tattoo artist Jackie Dunn Smith make quite the creative couple. Are any of your tattoos an ode to your work as a furniture maker?

I have one on my abdomen that’s a skull on top of three books. On the book bindings are the last names of three major eighteenth-century furniture designers: Thomas Chippendale, George Hepplewhite, and Thomas Sheraton.

How do people usually hear about your work?

I have no idea how people find me, and I am always surprised when they do. Usually I make something for someone and his or her friends see it and call me. I like it that way. Things always pop up.

Well, you were featured on the viral Instagram account Porn for Women, which shows men in real-life domestic scenarios that are SFW. Did that drum up some new business?

It was a picture of me sitting at my workbench looking at a notebook. The name of the site is misleading. Telling my mother about it was a little awkward.

What has been the most complicated piece you have ever made?

Nothing is truly simple. All of the pieces are complex in their own way. Chairs can be particularly complicated. I made a credenza once that had secret locks on the drawers. That was tricky.

For more information, go to dhphillips.com.