In one photo, Smith is in a tuxedo next to the former First Lady Nancy Reagan at a John Wayne Cancer Institute event in 2006. Documentary footage shows a much younger Smith teaching the late George Plimpton how to ride a horse in preparation for an appearance in the 1970 film Rio Lobo. In another photo, Smith poses in drag next to Maureen O’Hara on the set of the 1963 Western McLintock! (“He doesn’t make a very pretty woman,” his wife, Debby, affectionately observed.)

A blown-up image shows the photo finish of the 100-meter dash at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, where Smith finished fourth in what is regarded as one of the closest races in Olympic history. (He went on to win a gold medal that year in the 400-meter relay.)

Yet if Smith’s name remains little known, that is probably because he spent most of his life serving as a stunt double for actors (and occasionally actresses) who preferred to maintain the illusion that they were the ones falling from horses and leaping off buildings.

“You’re soon forgotten,” Smith said from the easy chair in his living room on a ranch that’s also populated by dogs, geese, chickens, horses, and fifty head of Longhorn cattle. “Time has a way of forgetting you.”

At 81, Smith may finally be getting his turn as the star attraction. In April, Texas Tech University Press will publish his memoir, Cowboy Stuntman: From Olympic Gold to the Silver Screen, co-written with Mike Cox of Austin. The book arrives as film scholars and directors are pushing for greater recognition of stunt performers.

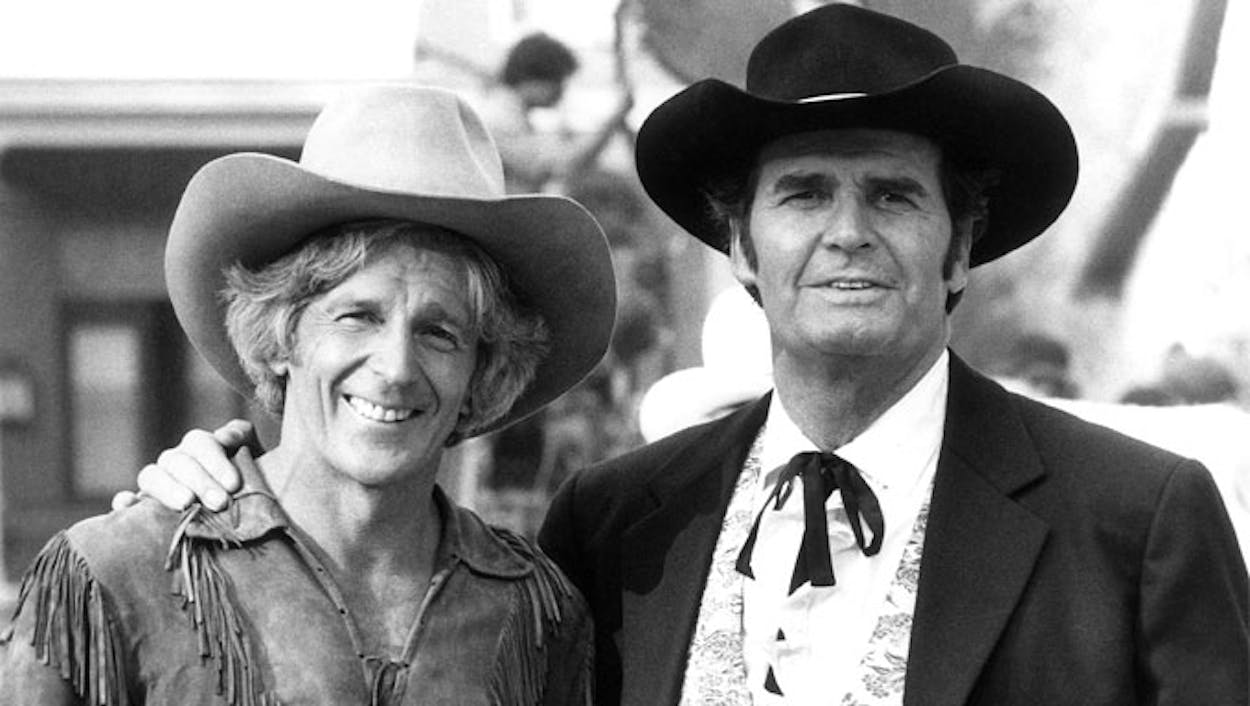

Born in Breckenridge, Smith was a star athlete at the University of Texas, where he ran track and played football. After the Helsinki Olympics, he served in the Army and spent a few months playing for the Los Angeles Rams before deciding to make a go at the movie business. A mutual friend introduced him to the actor James Garner, who helped him land his first stunt job on the television series Cheyenne. Having grown up on a ranch and competed in rodeos as a teenager, Smith was a natural for stunt work on westerns.

“I could ride, run and jump,” he said. “That was my life.”

What emerges from Cowboy Stuntman is an evocative portrait of the end of a Hollywood era, when the Western genre was quietly fading into the sunset. There’s an especially bittersweet passage when Smith attends a fiftieth anniversary screening of the 1960 version of The Alamo in San Antonio, and realizes that he is one of only five cast members still alive.

Smith continued working in Hollywood through the seventies and early eighties, and even landed a few small speaking parts. But eventually he realized that he was never going to make it as an actor, and in 1992, he returned to Texas. He lives now on the same ranch where he grew up, with Debby, his fourth wife, and their fourteen-year-old son, Finis.

“I’m not into any of that quitting stuff,” he says of his reluctant decision to leave Hollywood. “You still want to do something.”

He added, “If this book gets some fire going on it, I wouldn’t mind trying to get a meeting with Steven,” he says, referring to Steven Spielberg, with whom he worked on The Sugarland Express. (His wife said that she would like to see Matthew McConaughey play Smith.)

Will stunt men ever earn the credit they deserve? As recently as 2011, the Academy’s Board of Governors voted down a proposal to institute an award for stunt work. On the other hand, the casting of stunt performer Zoe Bell in Quentin Tarantino’s 2007 film “Death Proof” and the awarding last December of an honorary Oscar to stuntman and director Hal Needham would seem to hint at a shift.

“People might be getting kind of nostalgic about stuntmen these days, since CGI and ‘digital doubles’ are increasingly being used instead of stunt performers,” noted Northwestern University professor Jacob Smith (no relation to Dean), author of the 2012 book The Thrill Makers: Celebrity, Masculinity, and Stunt Performance.

And even if he was never as famous as the men he doubled for, Smith is not without his fans. On a recent Saturday, he visited the Old Post Office Museum and Art Center, in Graham, to preview a memorabilia exhibit mounted for a book signing event on April 17. A small coterie of local residents were there to greet him, including Marlene Edwards, the museum director, who remembered meeting Smith when she was in high school and he returned home for a visit, accompanied by his friend, the television star Dale Robertson.

“We were all excited by everything he did, and he would always come back to share it with everybody here,” she recalled. “He’s always been just Dean to us.”