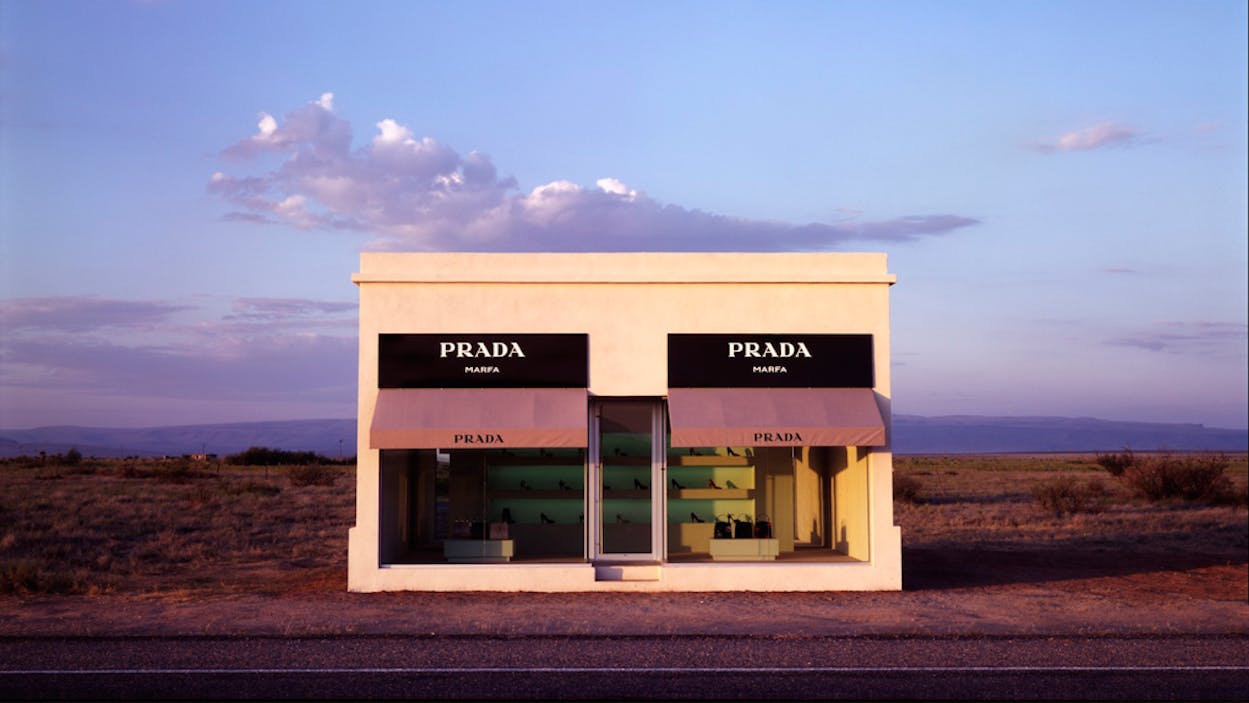

Prada, the Italian luxury-goods house, has plenty of impressive stores—in Milan, Paris, around the world. But its most exclusive is a 15-foot-by-25-foot adobe building in the Chihuahuan desert, 35 miles northwest of Marfa. It contains six bags (without bottoms, to discourage theft), twenty shoes (the rights only, for the same reason), and hundreds of dead flies (thieves, help yourselves). Since opening in 2005, it has also drawn thousands of tourists, including, last summer, Beyoncé. She was not allowed entrance. This store is so exclusive that its door is always locked.

That’s because Prada Marfa is not a retail store but a permanent installation by Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, Scandinavian artists based in Berlin. It is also, at the moment, the center of a controversy.

Nearly eight years after opening, Prada Marfa has been classified by the Texas Department of Transportation as an “illegal outdoor advertising sign” because it displays the Prada logo on land where that is prohibited. This could lead to forced removal of the installation, although the department has not yet decided what action it will take.

For the artists, the logo is essential to the meaning of the work. “It was meant as a critique of the luxury goods industry, to put a shop in the middle of the desert,” Elmgreen said.

From the state’s perspective, the logo is defined by state and federal law as a sign. And because the “sign” sits on unlicensed land bordering federal highway U.S. 90 and lacks a permit, it violates the 1965 Highway Beautification Act signed by president Lyndon B. Johnson, and championed by his wife, Lady Bird.

Prada Marfa’s artists have never considered obtaining a permit because they reject the idea that their piece is an advertisement. Miuccia Prada, Prada’s chairman, permitted the artists to use her brand’s logo. She also picked and provided the shoes. But there is, Elmgreen noted, “no commercial relationship.” The $80,000 project was paid for by the New York nonprofit Art Production Fund in collaboration with Ballroom Marfa, a local contemporary art gallery.

The Prada Marfa dispute joins the recent art-versus-advertising debate that has been agitating the 1,900-person town of Marfa since June, when Playboy Enterprises planted its own installation on the same highway, just a mile northwest of town. The controversial piece—a 1972 Dodge Charger on top of a box in front of a forty-foot neon Playboy bunny sign—was designed by the artist Richard Phillips for Playboy, which paid for the installation. The name, Playboy Marfa, parallels Prada Marfa, a move, it would seem, meant to attract the magnitude of attention enjoyed by the earlier installation.

It succeeded. But Playboy could be Prada’s undoing. The intense interest in Playboy Marfa, which the transportation department deemed in July an illegal outdoor advertisement because of its use of the trademarked Playboy bunny logo without a permit, now has some people, including the department, wondering whether the same logic could be extended to the Prada work.

State officials have been scratching their heads about this for weeks. Assistant Attorney General Oren Connaway, who was involved in discussions about Playboy Marfa’s legality, questioned Prada Marfa’s status on July 9, writing in an email, “Aren’t the fake PRADA MARFA store signs on US90 in Valentine illegal ads, too?” Wendy Knox, the transportation department’s supervisor of the Outdoor Advertising Regulatory Program, replied to him that the Federal Highway Administration had confirmed it was illegal—meaning the piece was determined illegal by both state and federal definitions of “sign.” “And we will take action on it,” Knox wrote.

What that means remains to be seen. The department will only note that “we are still working on this issue.”

Prada Marfa’s defenders, however, were happy to weigh in. “I would have thought the statute of limitations had expired,” said Boyd Elder, a local artist and the site representative for Prada Marfa. “It’s not an advertisement; it’s an art statement. And it’s on private property.”

That is true of the building, which sits on property owned by Carmen Hall. The awning, though, stretches over the right of way, an encroachment the department flagged as a second violation.

Prada Marfa’s creators say the piece had nothing to do with marketing. “There’s a difference between being commissioned by a company to do something for them and using their logo, and using their logo on your own,” Elmgreen said. Artists, from Andy Warhol to Ai Weiwei, he pointed out, have produced works that feature logos.

“If they want to remove it because of bureaucracy, we tear it down,” he said. “And then we can say that one of the quite well-known permanent artworks—that hasn’t cost taxpayers anything and that has been elected one of the most-worth-seeing roadside attractions in the States—is no longer.”

The news of the violation took Elmgreen by surprise. “If it really is against the regulations, they should have found out in 2005 when it was erected,” he said. “If I were head of the office there, I would fire the person who came up with this. This is a waste of taxpayer money.”

That reasoning may resonate in Texas, where many—regardless of how they feel about art—take a skeptical view of bureaucrats.

“Controversy is just more fuel for the fire,” Elder said. “Let it rip.”

Or in other words, come and take it.