The opening moments of the documentary Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four show the destruction of an American family. It’s July 12, 2000, and Anna Vasquez and Cassandra Rivera, a gay couple who had been quietly raising Cassie’s two children, slowly walk up a sidewalk in downtown San Antonio, then head into the Bexar County Courthouse, where sheriff’s deputies handcuff them. News cameras capture the women’s final moments of freedom, their families crying and saying goodbye before Anna and Cassie are led away to serve a fifteen-year prison sentence for aggravated sexual assault and indecency with a child.

What isn’t shown in the opening scene is that a third woman, Kristie Mayhugh, also reported to the authorities that day. A fourth, Elizabeth Ramirez, had been sent to prison a year before to serve a 37-and-a-half-year sentence. They were all convicted of the same crime: the 1994 gang rape of Liz’s two nieces, aged seven and nine. The children had claimed that the four women held them down in an apartment and sexually abused them using a tampon coated with gel and white powder, while pointing a gun or knife at their heads. The salacious accusations—four gay women assaulting two little girls—and a report by a pediatrician who examined the girls and found evidence of penetration rippled through the city of San Antonio.

Ever since their arrests in 1994, Liz, Cassie, Anna, and Kristie proclaimed their innocence, slowly picking up allies, especially after one of the girls recanted her testimony in 2012 and the pediatrician admitted that her trial testimony had been fundamentally inaccurate. Now the four women—who were all released on bail or bond over the past three and a half years—are fighting to be exonerated, and they have picked up maybe their most important advocate yet, Deborah Esquenazi, the director of Southwest of Salem. Her film premiered April 15 at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, and it is a remarkable achievement, a powerful narrative about crime and punishment seen through a lens of love, identity, and fear.

What makes Southwest of Salem even more extraordinary is that it is Esquenazi’s first feature film. The Austin resident uses a sure hand to guide the viewer through a complicated narrative, laying out the facts while still deftly conveying the intense emotion behind a story in which many lives were damaged. It’s a tale that at times feels all too familiar to people who follow the twists of the Texas justice system—just how easily a case can spiral out of control when people get crazy ideas in their heads and the law plays along.

The saga of the San Antonio Four began in 1994. Cassie and Anna were living together, raising two children from Cassie’s recently ended marriage. They spent a lot of time at the west side apartment of their friends Kristie and Liz, who were also gay. In fact, Liz had been emancipated from her mother’s home when she was fifteen, in large part because she was attracted to girls. But Liz was also attracted to boys, and now she was pregnant by a man she was dating. She was young, only 20, and so were the others: Anna 19, Cassie 20, and Kristie 21. They all had jobs and plans to go to college. None had a criminal record.

In September 1994, the women received calls from a detective with the San Antonio police department: Liz’s nieces alleged that the four had sexually assaulted them two months before at her apartment, where the kids were spending some time that summer. All four women insisted they were innocent. “You believe as you’re growing up that if you tell the truth everything’s going to be fine,” Anna says early in the film. “A couple of people told me, ‘You need an attorney.’ Why would I need an attorney? I’m innocent—there’s nothing that ever happened.”

The stories told by the little girls changed wildly from their initial statements to police to the trial testimony, with details shifting about everything from when the assaults happened (night, then morning, then in the afternoon), to where they happened (the living room, the bedroom), to who held a gun (Liz, Liz and Anna, just Anna), to who drove them home (their father, Kristie and Liz, all four women). Their stories involved pot and tequila. The children said at least two of the women had been topless. It sounded like a twisted orgy of brutality.

According to Liz, the whole drama could be blamed on the father of the girls, who, she said, had been making passes at her since she was fifteen, including sending love letters and proposing marriage. When she turned him down, Liz claimed, he fought back by coaching his daughters. (The man denied it then—and denies it today.)

But authorities chose to believe the girls and prosecute after they were analyzed by pediatrician Nancy Kellogg, director of Child Safe, a San Antonio child-advocacy institution, who said that a two-to-three millimeter white “scar” (about the width of a quarter) on the hymen of the nine-year-old could have been evidence of penetration. In her notes, Kellogg also wrote “this could be Satanic-related.”

At the time, the U.S. was still reeling from a wave of prosecutions during the eighties and early nineties of so-called Satanic ritual abuse. There had been numerous cases of children accusing adults of rape and torture at day care-centers or schools, acts fueled by worship of the dark lord himself. (One particularly infamous case took place just outside of Austin, a story covered extensively by Texas Monthly, both during the original trial and conviction, and the subsequent release of the accused, Fran and Dan Keller, whose convictions were later overturned, though they have not been declared innocent.) In these types of cases, there was rarely any physical evidence, just the stories told by children. The result was a slew of modern day witch-hunts that sent many innocent people to prison. In one of the creepiest parts of Southwest of Salem, Esquenazi evokes the fears behind witches and witch-hunts with clips from the 1922 Danish-Swedish silent film classic, Haxan, a macabre fictionalized documentary of witches under the influence of Satan, dreamlike images of an innocent naked woman sleepwalking through a landscape of demons and weird human-sized animals, drawn to do the devil’s will.

Liz was found guilty and given 37 and a half years. In February 1998 the other three were tried together. At this trial, jurors heard that the two girls had also previously made accusations that a 10-year-old boy had sexually assaulted them, but this didn’t affect the children’s credibility. Kristie, Anna, and Cassie were also found guilty and given 15 years.

It took a Canadian living 3,700 miles away to get the case some attention in Texas. In 2006, Darrell Otto, a research scientist and professor who lives in the Yukon Territory, was doing research on female sex offenders when he came upon an article about the San Antonio case. Otto had learned from his research that females rarely engage in sex abuse—and when they do, they always act alone. “This case,” he says onscreen, “you’ve got four women offending against two children. It just didn’t make sense.”

He began writing Liz, and it didn’t take long to become convinced she and her friends were innocent. He put up a website, Four Lives Lost, and eventually began making yearly pilgrimages to the central Texas prisons where they were living. He wrote a short piece for Texas Monthly in 2009 and also contacted the National Center for Reason and Justice, a group that investigates false allegations of child abuse. The NCRJ’s Debbie Nathan, author of a 1995 book called Satan’s Silence: Ritual Abuse and the Making of a Modern American Witch Hunt, took a close interest in the case, and the NCRJ began working with the women.

In 2010 Nathan contacted the Innocence Project of Texas; soon after, attorney Mike Ware interviewed the women on four separate trips to four different prisons. He was stunned by what—and who—he found. “It seemed impossible that any of these individuals would have been involved in a crime like this, much less teamed up to commit it together. The accusations were so inherently preposterous that had the women been Junior League ladies instead of openly gay, I think that law enforcement and the district attorney’s office would have been completely embarrassed to pursue the charges in any manner.” He wanted to be sure, so he got a second opinion. “I arranged for one of the most professionally respected polygraphers in the state, really the nation, to polygraph each one. His conclusion: all four were clearly telling the truth about their innocence.”

Meanwhile the Houston-born Esquenazi, who had studied English at the University of Texas at Austin before moving to New York in 2004 with the goal of being an investigative filmmaker, met Nathan, who became something of a mentor. Nathan told her about the San Antonio case and urged her to look into it. Esquenazi, who is gay, had been struggling with coming out. She was intrigued by the story but also by how the women’s sexuality had been portrayed. Esquenazi was familiar with the fears she says many gay people feel, that sociey will cast them as child molesters. “I wish I could convey the profoundly deep-seated fear that exists in many gay people that everyone else thinks we are predators,” she says, “especially when we’re around children.”

As Esquenazi read the trial transcripts, she became convinced that, more than anything, the case was about homophobia, four women being prosecuted for being lesbians, as if they were members of a dangerous cult that forced innocent girls to do their will. When Liz went on trial first, in 1997, the prosecutor said how “the evidence is going to show that young woman over there held a nine-year-old girl up as a sacrificial lamb to her friends. … We’re going to ask you to believe a nine-year-old little girl who was sacrificed on the altar of lust.” He questioned Liz about her sexuality—wasn’t she dating the other three women? No, answered Liz, “they’re all gay and we’re friends, but that doesn’t mean it’s a gay relationship. We’re all friends. It doesn’t mean we’re all intimate together, had any kind of sexual togetherness.” The prosecutor overtly asked the jury to not convict Liz because of her sexuality, though he added, “It’s only important in the sense that that activity is generally consistent with the activity alleged in the indictment.”

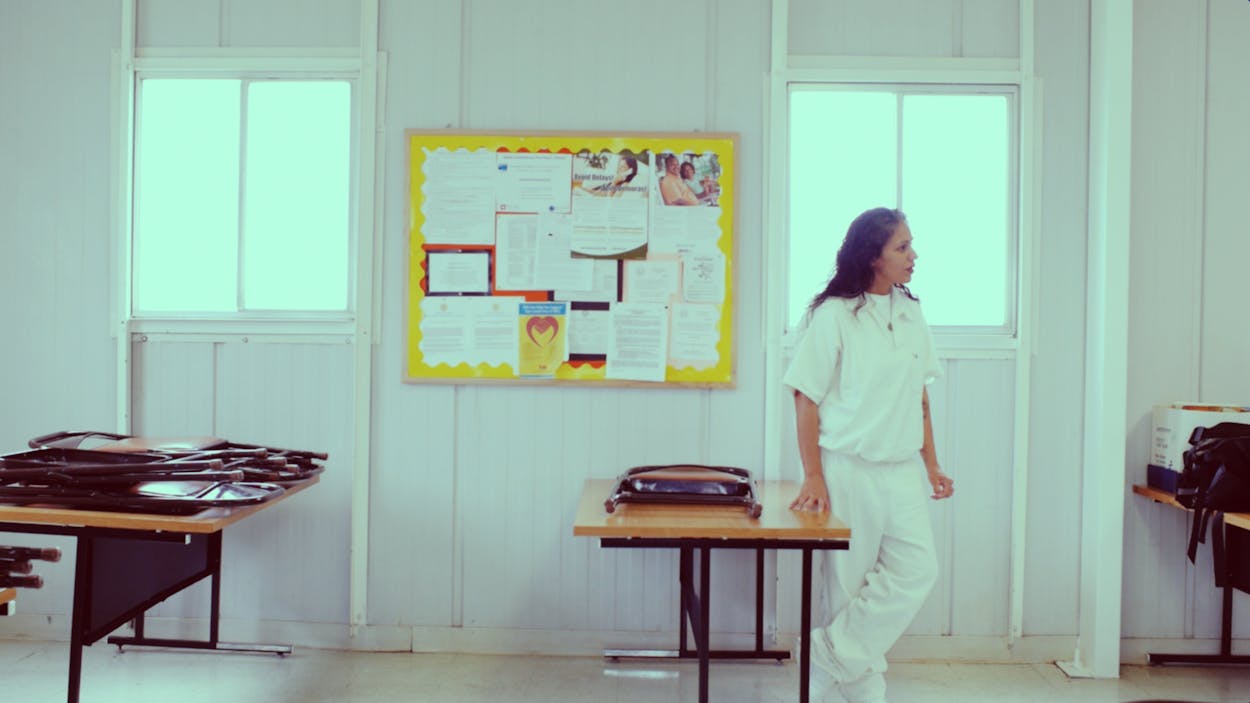

Esquenazi started filming in 2011, going to each prison, and getting long interviews with all four women. Her first was with Anna. “My name is Anna Vasquez,” she says, looking just past the camera, “I’m 37 years old, and I was born and raised in San Antonio, Texas.” Esquenazi’s debt to The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris’s classic documentary about an innocent man on Texas’s death row, is apparent in everything from her use of minimalist piano music to the look and feel of her interviews, how she lets the women, in prison whites, tell their stories. As they did, Esquenazi felt more and more felt comfortable with the ladies, to the point that she came out to each one individually before she did to her own family.

,And then Esquenazi got the kind of break investigative filmmakers dream of—the kind Morris got in The Thin Blue Line when the actual killer revealed himself on camera. Ware called her on August 4, 2012: Get to Houston, he said, Stephanie, the younger of the girls, wants to recant. Esquenazi took her camera to Houston and filmed Stephanie, at that point 25 years old and a mother herself, read into the camera a letter she had written her to her aunt Liz. Her father and grandmother had coached her, she said. It was all lies. “I’m sorry it has taken this long for me to know what truly happened. You must understand I was threatened and I was told that if I did tell the truth that I would end up in prison, taken away, and even getting my ass beat. I will make things right, and I’m sorry for everything I put you through. I was only seven and I was scared.”

Esquenazi knew that she was part of the story now, not just its documentarian. She alerted Michelle Mondo, a reporter for the San Antonio Express News who had written a long, detailed, and skeptical article about the case, in 2010. After Mondo wrote about the recantation, local news stations began doing segments on the case as well. The San Antonio Four were finally getting some sustained media attention.

They got more good news in November 2012 when Anna was released early on parole. Esquenazi was there for the tearful reunion with her mother. “A week out here in the world is like a year in prison,” Anna says as she starts navigating the world again, learning about cell phones and modern cable TV. She helps family members hold fundraisers for the remaining three, including a car wash and barbecue on the west side of town.

Meanwhile Ware, aided by defense attorney Keith Hampton, was working on writs of habeas corpus for all four. In October 2013 the attorneys filed the writs in San Antonio based on Stephanie’s recantation as well as a new state law that allowed inmates to contest convictions that were based on outdated forensic science. The science of hymens, for example, had changed considerably since 1997. A 2007 study by the American Academy of Pediatrics said that “torn or injured hymens do not leave scars as a matter of fact.” Kellogg gave an affidavit; she had reviewed the evidence in light of current understandings of the science, and wrote, “I cannot determine with reasonable medical certainty whether [the older girl’s] hymen had ever been injured at the time of the 1994 examination.” Today, she said, she wouldn’t have testified the girl had been abused. The Bexar County DA agreed to vacate the sentences and released the remaining three in November 2013.

On November 18, a huge crowd gathered outside the county jail. Esquenazi was there with her camera, and she recorded one of the most powerful slices of real-life criminal-justice drama you will ever see on film. First the four, led by Ware, emerge to cheers from families and friends, Cassie followed by Liz, Anna, and Kristie, all holding hands, all raised high. Then the four fall into the arms of their parents and children. Cassie holds her grown weeping son, whose face is buried in her arms. Liz’s mother, who had spurned her so many years before, desperately grips her daughter’s head and peers into her face, her own eyes wet, cooing “Ay, mija” and hugging her as if she thought she’d lose her again. Cassie touches her granddaughter for the very first time. “Oh, my god,” she says, crying. “I’m your grandma, baby” and kisses her forehead. By the time the four get into a car and drive away, they’re smiling, even laughing. They’re finally free.

The story of the San Antonio Four is dramatic enough on its own; much of the power of Southwest of Salem comes from the person behind the camera. As the women are literally coming out of prison, Esquenazi was going through her own coming out, determined to make a movie that didn’t skirt sexuality but embraced it. The film takes great care to show the women living their lives, the ordinary moments in which they do what everybody else does—go to church, shoot pool, kiss on the beach. At one point toward the end of the film, Liz and Kristie acknowledge that they are dating, and the camera catches them having a mild disagreement about it, the kind that all couples have. “It was kind of weird at first, right?” asks Liz. “We fought it, right?” Kristie laughs vigorously but awkwardly, offering, “I don’t think it was weird.” After a few moments, she compromises. “It caught us both by surprise.” Liz agrees, “Okay, that’s good.”

Southwest of Salem also gives a palpable sense of the women’s personalities—the religious Liz, the emotional Cassie, the quiet Kristie, the stoic Anna. The four have stayed close since the release—“We all come as one package,” Liz says, “from the beginning, and we’re gonna stay that way”—getting together socially and for their cause at panels and community gatherings. Before each one, the four bow their heads and Liz leads a little prayer, asking God for protection and guidance.

Liz’s reconciliation with Stephanie is probably the most heartrending scene in the film. Liz, who hasn’t seen her niece since the trial, tells Stephanie, “I just want you to know I’m not mad,” before starting to cry. “I’m glad you came forward.” Stephanie begins to cry too, and Liz scoots over on the couch they’re sitting on and wraps her arms around the woman who, years before, helped send her to prison. “I’m so sorry,” the younger woman says, shuddering with tears, her head hidden on her aunt’s shoulder. Liz pats her on the back. “That’s okay.”

The final segment of the film lays out the rocky legal road the four still have to walk. Esquenazi filmed a 2015 hearing regarding the writs of habeas corpus at which Judge Pat Priest—who had overseen the case against the three back in 1998–hears recommendations on whether to recommend to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals that the four should be given new trials or be found actually innocent. In February 2016 he gave his ruling: Yes, the four deserved new trials. However, the judge wrote, even though Stephanie had recanted, even though the girls’s father had been found to have made false allegations that not one but two others had sexually assaulted his kids, even though there was no hard scientific evidence pointing to the four women, “the evidence does not unquestionably establish innocence.”

All four were deeply disappointed—they were still, in the eyes of the law, convicted rapists. Ware, an optimist by trade, urges them to be hopeful. “We’ll continue arguing this case at the Court of Criminal Appeals,” he says offscreen, to the stately rhythm of a doleful string quartet. “I think we’ve got a shot.”

The film ends there, but their story does not. The four women were invited by Esquenazi to attend the premiere tonight in New York, but they have to get permission to travel beyond 75 miles of San Antonio. Ware got the okay, and they flew to New York, the first time any of them have been there (on Wednesday they visited the Statue of Liberty and 9-11 monument). But when the film is screened again at Toronto’s prestigious Hot Docs conference on May 4, Esquenazi and Ware will be in attendance; the four women won’t be. “They received their passports and a court order permitting travel to Toronto,” says Ware, “but because of the sex offender convictions still on their records, Canadian customs would stop them at the border deny admission and send them home.” So they’re staying in San Antonio, where they will participate in a panel discussion, co-hosted by San Antonio’s Cinefestival, to be held at the same time as the film showing.

Tonight in New York, before the film is shown, once again Liz, Cassie, Kristie, and Anna will bow their heads and Liz will lead a prayer. Ultimately she and her friends hope and pray that the film, which Esquenazi thinks will have wide release in six months, will do what the justice system hasn’t done yet. “I’m hoping when everyone sees it,” says Liz, “they’ll see the truth, and that the CCA will act on it. The truth is that this was a crime that never happened. All we want now is to be exonerated, to clear our names.”

- More About:

- Film & TV