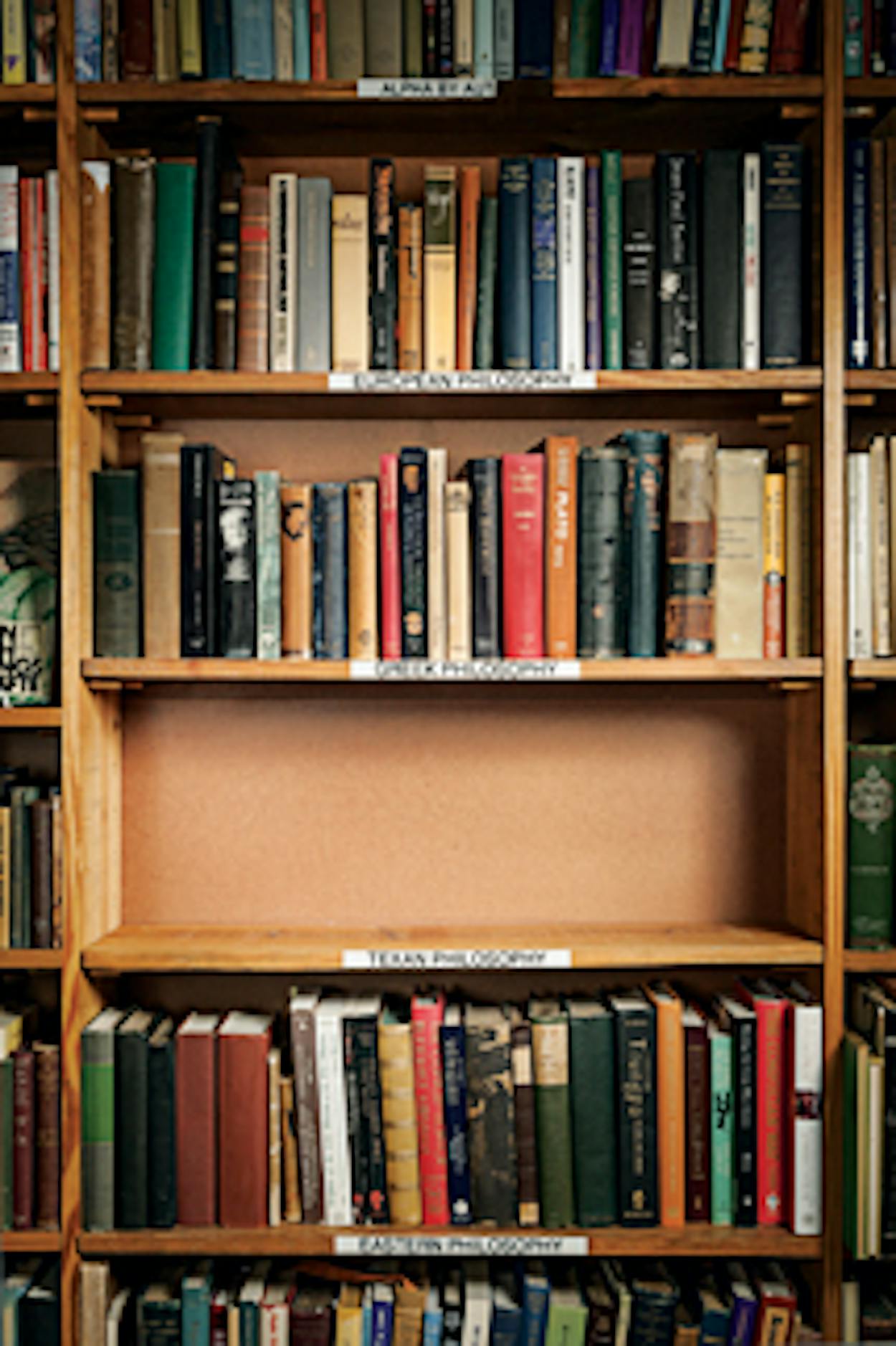

There is an old adage, which may go back to antiquity, that at the dinner table the upper classes debate ideas, the middle classes discuss things, and the people talk about people. In Texas, though, ideas have never dominated society at any level. Being Texan may be a state of mind, like being French or Russian, but the people who settled Texas were primarily people of action. They did things, sometimes great things, but they rarely contemplated their meaning. As for basic beliefs, they brought those with them over the Rio Grande or the Sabine. If a historian looks back, he finds entrepreneurs, soldiers, and canny politicians, from Sam Houston to LBJ, but few things intellectual that germinated in our soil. Texas is now rich and powerful, but we still talk up other men’s ideas.

My ancestors came here mainly to get land. This was not unique to Texas. Nearly every European crown or government staked its claim on parts of America. But every government of Texas, from colonial times to statehood, gave away its public lands. Geography compelled this: Texas is huge, and for a long time, people were more valuable than land.

Nineteenth-century North American and European immigrants wrote more about “land” than “opportunity” or “freedom” as their reason for coming to Texas. The “Texas Dream” thus had a scent of empire-building—a family upon its own soil—that has always contrasted with the American dream of a job, a home, and a car. Some of that still applies: West Texas ranchers speak of their property as their “country.” Land was wealth, wealth was land in early Texas. Owning land was the road to personal and financial independence, a desire that is still embedded in the Texan soul. (Since government, harsh or helping, always interferes with independence, there is distaste or even fear of Washington in Austin, and of Austin beyond the Pecos.) Many Texans, however they make their money, still like to have a “ranch.”

My grandfather Charles Columbus Wentz was well educated, but I believe his greatest love was his property, which he visited almost every day. My great-grandfather Major Milton Reed did the same by horseback, or so my mother said. In any event, conversation when people met concerned weather, crops, and prices—practical things. People battling frontier conditions, which lasted well into the twentieth century, have neither the time nor inclination to discuss philosophy or the brotherhood of man. (Grandfather may have been able to recite Cicero verbatim, but in the nineteenth century being able to quote Latin or Greek often substituted for thinking.)

The family my father married into had acquired land, enough to live on from the rent. As a boy I could hunt and fish on the home property and, under then–Texas law, impound stray horses that had been let loose on it. I was taught to respect others’ property; fence lines were sacred. I do not write this to be personal but to explain why my viewpoint will always be different from, say, Mitt Romney’s or President Obama’s. A little Latin and less Greek and a smattering of Ivy League conventional wisdom do not easily erase tribal instincts.

Most Americans pay too little attention to geography and history, which profoundly shaped Texas values. These favored pragmatism and courage. When Europeans arrived, Texas was a vast territory populated only by tens of thousands of aborigines. The dominant culture was based upon bison hunting and endemic warfare. This, and the huge spaces of western Texas, made it hard to conquer, but the Plains Indians’ dependency on the buffalo proved fatal when the buffalo were slaughtered. To destroy the basis of an economy, whether slavery or buffalo, was to destroy that economy. Our ancestors did not “win” the West by accident or inattention; from the outset, future Texans went westward to conquer the wilderness and any other obstacles that impeded them. The rightness of this was questioned, but never on the frontier. As always, when two rights came into conflict, a contest at arms, not a public debate, decided the issue.

The Indian wars in Texas were among the bloodiest of the continent’s struggles between the newcomers and the native population, and they created a violent frontier that lasted more than a generation. The historian Walter Prescott Webb saw Texans fighting a three-cornered war in the nineteenth century: Mexicans, Yankees, and Indians. But Texans also had to battle climate, weather, the Industrial Revolution, modernity, and the land itself. Frontier conditions, and the wearing of weapons, lasted well into the twentieth century. For that matter, weather, climate, bugs, and bad water remain problems, and many of us still go armed.

This created certain attitudes (“We fought for this land, we took it, we mean to hold it”) that may account for the noticeable belligerency displayed by Texans in twentieth-century wars. Proportional to population, more Texans were killed during the past century than men from any other state. Before Pearl Harbor, Texas was the state most ready to go to war against the Axis. And I remember, as a boy, being advised that it was better to take a whupping than to back down.

Leaving aside all the violence, color, and romance of the Heroic Age (the Alamo and all that, the Indian wars), the threads of Texas history are like spaghetti trails. They lead somewhere, but we’re not sure where. Our nineteenth-century past, despite constant academic squealing, has become a canon, but nobody agrees on exactly what happened afterward and why, and Texans are often not much interested in what those outside our borders—or the dissenters within them—have to say about it.

We found out that we are mineral rich in ways our ancestors couldn’t have dreamed, and holding on to a piece of Texas may make you rich in the fullness of time (think of the Eagle Ford Shale, once brush country), but from cotton to calves to gas, Texas remains something of a colonial economy: we still export huge quantities of raw materials. Agrarian and mining complexes are normally politically conservative, and their owners define our state’s culture more than do managerial types. Some Texans still think of professionals as hired hands.

A cultural bias against the corporate way of life can be found even among Texans who run large corporations. However simplistic, there is something neat and clean about the concept of owner, foreman, tenant, and ranch hand. To a Texan, there is something messy about CEO, board member, supervisor, manager, salesman, laborer, and stockholder of the nanosecond, even though “progress” and necessity created all of these. This is why the western, our greatest genre of literature, will somehow stay alive.

No, Texas was not built on ideas. But it is no longer anything resembling cowboy country, and it’s time for us to stop thinking about the things I’ve written above and to look for meaning. Is there meaning to Texas’s history and culture? Or is it all chaos tinged with evil?

Our ancestors made us rich enough to stop talking about prices, crops, politics, or oil and to start debating concepts and meaning. This, after all, is what great and mature societies do.