At the time of her death, at the age of 23, Selena Quintanilla Perez was many things to many people: cultural icon, role model, sex symbol. Above all, she was a study in contradictions. The Queen of Tejano Music was a third-generation Texan who initially struggled to speak Spanish, even as her Spanish-language songs, which she had learned to sing phonetically, climbed the charts. She was the third-highest-earning Latino performer in the U.S. but remained a down-home girl even after winning a Grammy. (Her one concession to stardom, a red Porsche, was often parked just beyond the chain-link fence outside her unassuming Corpus Christi home.) Her final concert at the Astrodome broke all previous attendance records, and yet to many Anglos, she was a complete unknown.

That changed on the morning of March 31, 1995, when Selena was murdered at a Corpus Christi motel, shot once in the back by Yolanda Saldivar, the president of her fan club. News of her death was greeted with the sort of widespread mourning usually reserved for a political assassination. For Selena’s fans, writes ethnomusicologist Manuel Peña, “it was as if their collective aspirations, embodied in this sultry, yet down-to-earth, barrio-bred hermana (sister), had been punctured just as surely as the bullet-shattered artery that killed the young diva.” When her first English-language album, Dreaming of You, was released posthumously that summer, it sold 175,000 copies in a single day. Selena became a crossover star only in death.

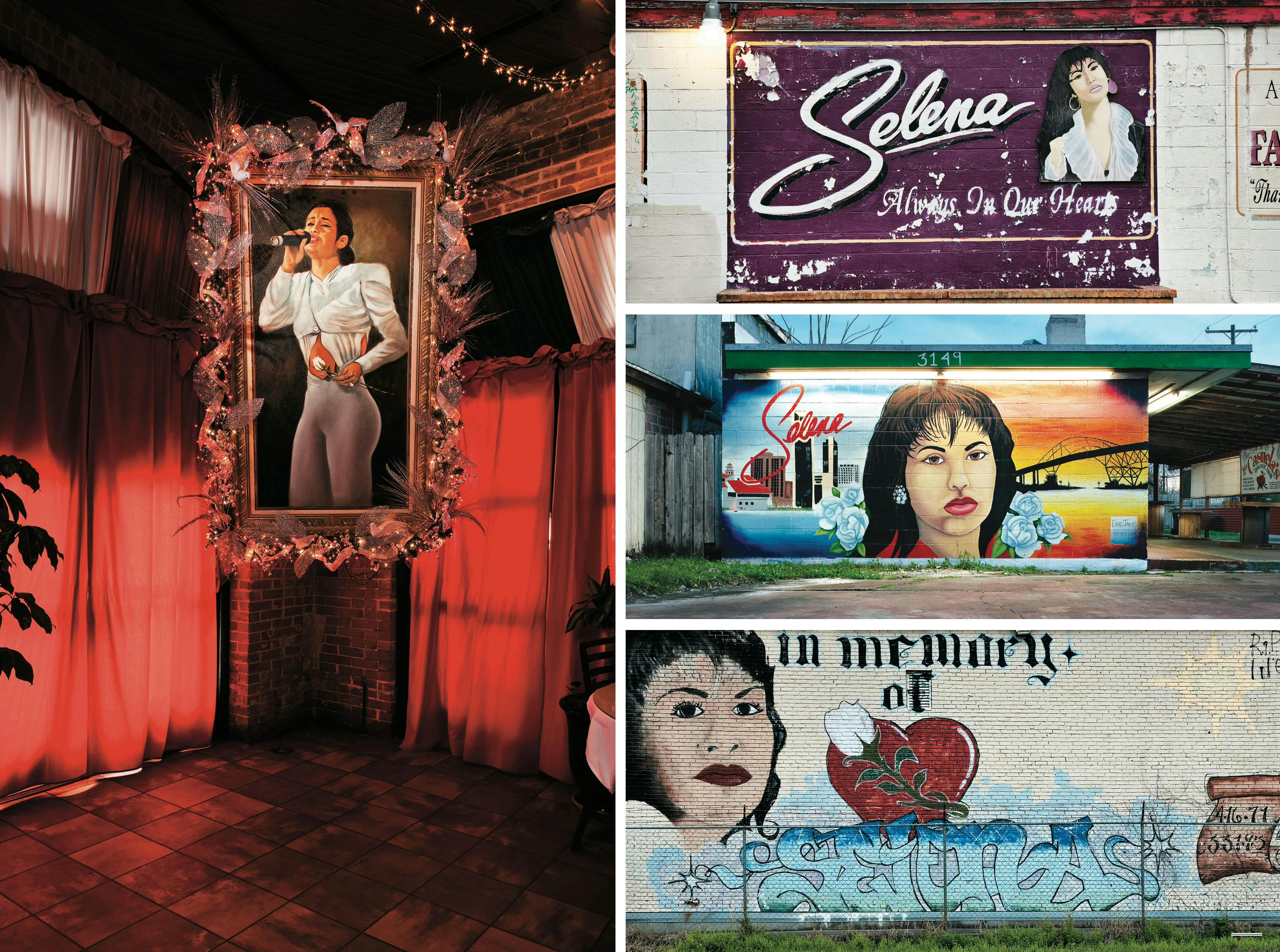

Since then, Selena has been canonized, sanctified, and resurrected. There has been a glossy Hollywood biopic, a touring musical, and talk of featuring her on a postage stamp. In South Texas and beyond, she has been elevated from popular singer to something more ethereal: cult hero, martyr, patron saint. Thousands of her fans still travel each year to Corpus Christi, where her family’s recording studio—as well as her home, former boutique, grave, and memorial—has become Texas’s own Graceland.

Fifteen years after her death, Texas Monthly asked those who knew Selena best to look back and reflect on her life, her music, and her legacy. Here, for the first time, all the prominent players in her journey from obscurity to fame—her family, her husband, her bandmates, her childhood friends, the fashion designer with whom she collaborated, and the record executives who recognized her talent early on—tell her story in their own words, and consider what might have been.

“Selena Quintanilla Perez . . . is presumed dead.”

As reports of Selena’s death broke on the afternoon of Friday, March 31, 1995, South Texas was consumed by grief. Anguished fans gathered at the Days Inn where she had been shot; at her clothing boutiques in Corpus Christi and San Antonio, which were hastily transformed into shrines; and at impromptu vigils around the country. Outside Selena’s home, mourners paid tribute with flowers and photographs; the line of waiting cars measured five blocks long. Around-the-clock news coverage on Spanish-language television and radio stations was followed by front-page stories in the New York Times and other major newspapers, which compared her killing to the shooting of John Lennon.

LUIS “BIRD” RODRIGUEZ, whose voice-over begins Selena’s hit “La Carcacha,” is a deejay at Z-93 in Laredo. I was on the air when a deputy sheriff friend of mine called to tell me the news. I was in a state of shock. I kept thinking, “This can’t be happening. Please, God, this can’t be happening.” I stopped the song I was playing and said, “Selena Quintanilla Perez was shot in Corpus Christi this morning and is presumed dead.” The phones lit up; no one could believe what I was saying. The mood was very somber. I played Selena all afternoon, nothing but Selena.

DANNY NOYOLA was the principal of West Oso High School, in the Corpus Christi neighborhood of Molina, where Selena lived. He is now the assistant principal at Foy H. Moody High School. I went on the school’s PA system and announced that our great Selena Quintanilla Perez had died. I said that we had lost one of the greats and that we would never, ever forget her. I managed to keep my composure, but as soon as I was done, I went into my office, closed the door, and cried.

RAMIRO BURR was a San Antonio Express-News music writer for fifteen years. He is the author of The Billboard Guide to Tejano and Regional Mexican Music and lives in San Antonio. I was driving down to Corpus the day after she was killed when I noticed that a lot of cars on the highway had their headlights on. I remember thinking, “That’s weird. Is it a holiday?” And then it slowly dawned on me: This is for Selena.

CARLOS VALDEZ has been the district attorney of Nueces County for seventeen years. In late 1995 he prosecuted Yolanda Saldivar for Selena’s murder. He lives in Corpus Christi. No one could believe how many mourners showed up to Selena’s public viewing at the convention center on Sunday. The police estimated that over 50,000 people came to pay their respects, but I believe it was closer to 100,000. The line went on forever—I have never seen anything like it. Reporters were calling my office from all over the world—Europe, South America, Australia, Japan.

RUBEN CUBILLOS was an associate creative director at Sosa, Bromley, Aguilar & Associates, where he worked on Selena’s Coca-Cola advertisements. He is now the president and executive creative director of A Big Chihuahua, a San Antonio advertising agency. The line was already four blocks long by the time I got there. The whole scene was in the realm of the surreal, like Elvis had just died. People had written messages on their car windows in white shoe polish: “We love you, Selena!” “We’ll never forget you!” Seeing her was mesmerizing. She was surrounded by roses, thousands of white roses.

YVONNE “BONNIE” GARCÍA is the former director of Hispanic marketing for Coca-Cola North America and signed Selena to her first contract to be a Coke spokesperson. She is the founder of Marketvision, a multicultural marketing agency in San Antonio. It was like losing someone in your own family. For millions of people, her death was felt that deeply; it was that personal of a loss. Selena hit a chord with all age groups—from my little nieces, who could barely talk but could sing “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” in its entirety, to my mother, who was in her sixties and liked to sing along with them.

JOE NICK PATOSKI was a Texas Monthly staff writer for eighteen years. He is the author of Selena: Como La Flor and Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. He lives in Wimberley. When Selena was killed, most Anglos didn’t understand what all the fuss was about. They hadn’t heard her music, and they didn’t know who she was. So there was a huge divide between the way Anglos and Mexican Americans reacted to the news of her death. For many Mexican Americans, it was like the day that Kennedy was assassinated.

CAMERON RANDLE was the vice president and general manager of Arista/Texas and its Latin music subsidiary, Arista/Latin. He is now a priest and the associate rector at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Hollywood. Selena’s story was incomplete when she was killed. Her career had been an exhilarating ride upward, and then all of a sudden it came to a very unexpected and tragic end. No one will ever know whether she would have been successful as a crossover artist had it not been for her death.

DANIEL GLASS is the former president and CEO of EMI Records. He is now the CEO of Glassnote Entertainment Group, in New York City. Oh, she would have been—undoubtedly—one of the biggest stars in the world. Selena was going to be huge not only in Latin music but in the mainstream market. She would have been up there with Mariah Carey, with Madonna, with the great ones.

“Oh, my gosh, that girl could sing!”

The youngest of three children, Selena Quintanilla was born in Freeport on April 16, 1971. Her musical talent was cultivated by her father, Abraham, a singer who had crooned doo-wop in the late fifties with his own band, the Dinos. Selena’s eventual mass acclaim would come as a stark contrast to Abraham’s experience a generation earlier, when the Dinos, despite having a hit on Corpus Christi’s pop radio station, were unable to break into the Top 40. The band ultimately found modest success by turning to Tejano, a Texas-born genre influenced by both American and Latin music that mixes elements of pop, jazz, and country. They played Spanish-language hits in dance halls around the country until Abraham settled down and took a job with Dow Chemical in Lake Jackson, in 1968, so he could spend more time with his wife, Marcella, and their growing family.

BECKY COOPER lived around the corner from the Quintanillas and attended elementary school with Selena. She is now a biology teacher and softball coach at Brazoswood High School, in Clute. Selena was a stringy little kid, and God love her, she had the worst hair in the world. Don’t let anybody lie to you. This was the seventies and the early eighties, so everyone wanted that long, bone-straight hair. And her hair was a mass of curls, with one curl going left and one going right and one sticking straight up. She and my cousin and I were all tomboys, so we spent most of our time playing outside. Selena was goofy and sweet and she had a good heart. And when I say goofy, I mean goofy. She would make us laugh until we snorted.

ANNIE PEREZ was Selena’s third-grade teacher at O. M. Roberts Elementary School. She is retired and lives in Lake Jackson. Most of the kids at O. M. Roberts were from a nice, middle-class addition in Lake Jackson. I was the only Hispanic teacher at that time, and Selena was the only Hispanic kid in my class. She was a very outgoing, friendly little girl.

A. B. QUINTANILLA is Selena’s brother. A producer, songwriter, and bassist, he founded the chart-topping Kumbia Kings and Kumbia All Starz. He lives in Miami. There were no Mexicans where we grew up. We didn’t speak Spanish, and we weren’t raised on Spanish music. We grew up with no influences whatsoever from our culture.

BECKY COOPER: It was a starter neighborhood for Dow families, so Selena’s dad, my dad, and most of the dads in our neighborhood worked at Dow. It was a pretty idyllic place to grow up, with lots of moms who stayed home and baked cookies.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA is Selena’s father. He is the CEO and president of Q Productions, a music production company in Corpus Christi. I had gone from living the nightlife to living in a town where everybody was in bed by nine o’clock. I felt like a caged lion. All I wanted was to get back into music, but I had a family to support. It was a very stressful time in my life. I went to my job every day, and I was there physically, but my mind was not there. Even though the dream I’d had of making it had ended, it never left me. I tried to settle into life in Lake Jackson, but I thought about music all day long.

BECKY COOPER: Selena’s father was very strict and kept her close to home. We never saw her past the time that kids were allowed to run around the neighborhood and play. They were Jehovah’s Witnesses, so they didn’t celebrate her birthday and stuff like that. She wasn’t allowed to sleep over or spend a whole lot of time in other people’s homes.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: Every day when I came home from work, I would get out the guitar and start messing with it. Selena would come sit next to me and listen. One day when she was about six years old, she started singing along with me.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA is Selena’s sister and was the drummer in Selena’s band. She is the vice president of operations at Q Productions and lives in Corpus Christi. Dad was taken aback by how good her voice was. He was already teaching A.B. how to play the bass, so I got drafted to be the drummer, which was a constant fight with me, because I couldn’t stand it. Girl drummers were not exactly cool back then. Dad converted the garage into a soundproof space, and we rehearsed there every day for thirty minutes.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: Dad was a musician, so he wanted people to jam with. We were the nominated people. We just kind of went along with it.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: One day a friend of mine at Dow said, “You know what Lake Jackson needs? A good Mexican restaurant.” The next thing I knew, we had leased a space and hired some ladies from Mexico to cook, and we were in the restaurant business. I built a small stage and a dance floor in the middle with tables around it. I would get up there and play with my kids, and people would come eat dinner and dance.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: The selection of music that Dad picked wasn’t exactly exciting, so we weren’t very happy about that. It was back-to-back slow songs: “Feelings,” “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights.”

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: We didn’t enjoy performing at first. I remember A.B. would get really embarrassed because he was in high school and the popular kids would be there eating with their families. I was in middle school, and I didn’t want to be looked at. I just felt really self-conscious. Selena didn’t seem to mind it, though.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I taught my kids to persevere. Back when I was with the Dinos, we ran into a lot of rejection because we were Mexican. We got invited to play a rodeo in Madisonville with some big-name artists in the mainstream market: Johnny Tillotson, Ray Stevens, Ray Peterson, the Five Americans. On our way to the show, we were asked to sit at the back of the bus. And when we got to Madisonville, we were told there weren’t any rooms available for us. It was a different time, you know? When we were growing up, our teachers spanked us if we spoke Spanish in school. By the time Selena came around, things had changed.

RENA DEARMAN played keyboards and sang backup vocals with the Quintanillas from 1981 to 1983. She is now a legal secretary in Houston. Selena didn’t have any moves yet—she was only nine years old. She would sing with one arm at her side, holding the mike in front of her, swaying back and forth. But oh, my gosh, that girl could sing! I used to listen to her and wonder, “Okay, where is that coming from?” Of course, she worked on her technique over the years, but she had “it” from the start. She was a complete natural.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Sometimes Selena would fall asleep behind the speakers between sets. She was still a little kid, so performing really wore her out. It was impossible to wake her up, and afterward she was grouchy and did not want to sing.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: Business was great at the restaurant; we had lines out the door. Things were going so well that I left my job at Dow. Then the recession hit, and people stopped eating out. We didn’t have the capital to ride it out, and we lost the restaurant. We lost the house. We lost everything.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Dad would only take us to the grocery store really, really late at night so no one could see that we were on food stamps. Things got bad enough that we had to move into my uncle Eddie’s trailer, in El Campo.

BECKY COOPER: When Selena moved away, it came as a complete surprise. It was one of those things where one day her family was there and the next day they were gone. She either had a tremendous amount of respect for not talking outside the family or she didn’t know they were leaving. Because she didn’t tell anyone; she just disappeared.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I drove a dump truck in El Campo, and then I moved us to Corpus Christi to find better work. My brother Hector gave us a room with one bed.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: There were thirteen people living in that house, and one bathroom, so you can only imagine. It was rough. I slept on the floor for about a year.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I went to all the chemical plants in Corpus Christi, thinking my experience at Dow would open some doors, but they all turned me away. They told me I was overqualified, which was a nice way of saying that I was too old.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: One time Dad took us to a garage that belonged to my uncle Isaac. It was in a really bad part of town—there were a lot of street people walking around—and the place was filthy. The floor was covered in oil stains. Dad said, “Look, we can fix this up and we can live here.” Honestly, I couldn’t see a dog living there. We all started to cry, and then Dad started to cry. He had this expression on his face that was indescribable. You know the pride that a man takes in providing for his family? His pride was gone. He looked defeated. That’s when it hit home how bad things were.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I couldn’t get a job anywhere, so I told Marcella that I was going back into the music business. Music was the only thing I knew how to do. The band was the best thing we had going for us. We all agreed to try and make a go of it.

“We actually started to dig the idea of being rock stars.”

Hoping to trade on the success of his old band, Abraham named the family act Selena y Los Dinos, and on weekends, they played any gigs he could book. When Selena was in junior high, Abraham took her out of school and enrolled her in correspondence courses so the band could stay on the road year-round. Soon they were crisscrossing the country, playing the Dinos’ old stomping grounds, from California to Florida. By the mid-eighties they had a string of regional hits: the pop confection “Oh Mamá,” the sentimental ranchera “Dame Un Beso,” and a salsa-style version of “La Bamba.”

A. B. QUINTANILLA: We played VFW halls, American Legion halls, ballrooms, skating rinks that doubled as dance halls. We played quinceañeras, weddings, anniversaries—you name it, we played it. If somebody wanted us to play and they had the money, we went.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Dad made our stage lights out of empty peach cans. He hung the cans on a pole, put colored gels inside them, and rigged the whole thing up to a bunch of light switches. Mom would sit there and run the lights.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I started calling all the promoters I knew from my time on the road. One guy told me, “Look, Abraham, they’re kids. Who’s going to pay to come see a bunch of little kids?” The only way they would agree to hire the band was if they could pay them practically nothing.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: Dad made sure that anyone who played with us always got paid. The family got paid in Whataburgers.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: In the beginning, there were a lot of nights when the kids played to an empty house, and they would get discouraged. I told them, “Play your hearts out and win over the people who are here, and the next time we come through, they’ll remember you and they’ll bring their friends.”

RENA DEARMAN: Selena was so young. I think it was hard for people to let loose and get down and dance—or get swept up in a love song—when there was a little girl up there singing.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: We made the decision to concentrate on the Tejano market. It was a regional market, and it was a market I knew. I understood Tex-Mex culture, and I knew which songs—the crying-in-your-beer songs—would hit people in the heart. I told Selena, “If you hit them in the heart, you’ve got them in the pocket.”

A. B. QUINTANILLA: We didn’t like Tejano music; we just didn’t get it. We didn’t speak Spanish and we weren’t raised on Spanish music, so it was kind of foreign to us. We preferred playing what we heard on the radio. Rehearsals were dreaded; nobody likes trying to perfect something, let alone in a language you don’t understand.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: Selena learned to sing Spanish phonetically. She had a lot of problems with pronunciation, so I would sit down with her and go over and over and over the words of each song until she finally pronounced them right. Then I would tell her what each sentence meant so she could put the right feeling into the song.

BRIAN “RED” MOORE was a recording engineer at Manny Guerra’s Amen Studios, in San Antonio, where Selena y Los Dinos recorded five albums for their first label, GP. In all, he worked on more than ten Selena albums. He is now a recording engineer at Q Productions. Those early days in the studio were hard on her. Abraham and Manny would both be in there, correcting her pronunciation until she sang it right. That would be hard on any twelve-year-old girl, to have two guys in there correcting and correcting and correcting.

LITTLE JOE HERNANDEZ, a pioneer of Tejano music, has been called the King of the Brown Sound. He fronts the band Little Joe y La Familia and lives in Temple. I grew up in Texas at the same time as Abraham. Like him, in school I was made to feel ashamed about my language, my food, my culture. I was made to feel ashamed about the color of my skin and the size of my family. So that was a twist, all those years later, when Selena had to learn Spanish to achieve her stardom.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: People expect you to have your own bus if you are a successful band. So I bought a bus. It was a ’64 Eagle that we called Big Bertha. It had no power steering, no heating, no air-conditioning. Half the time I was under the bus working on it. Wherever we had a gig, we would park the bus outside so people would say, “Wow, this band must be making it!” They had no idea it was a piece of junk.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: It had no running water, no electricity, and no restroom. During the winter, we slept near the motor, because it was hot back there. During the summer, it was horrible because you couldn’t pop the windows open to get a good gust of air.

LUIS “BIRD” RODRIGUEZ: I went on the road with them a few times, and I remember everybody falling asleep on the bus after gigs, except for Abraham. He would stay up all night and drive to the next gig. Abraham was forever driving.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Life on the road was fun, but we missed out on a lot. If we went to a school dance, it was because we were the entertainment. Me and Selena would talk about guys between sets, like, “Did you see that guy in the front? Wearing the blue shirt? He was cute!” After the performance was over, when guys would come up and ask for autographs, Dad would tell us, “Straight to the bus!”

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I kept them on a short leash. Fans would come up to me in every town we played and say, “Hey, after the dance, can the band come over to my house?” But no, there was none of that. I made sure the kids were always with us.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Most people think our rise to stardom was quick, but it wasn’t. We had been performing for six years at outdoor festivals and local clubs and little bitty dance halls before we started hearing our music on the radio.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: The first song I wrote for Selena was called “Dame Un Beso,” and it was a huge hit in ’86. It got played a lot on the Tejano radio stations.

RAMIRO BURR: That year, Selena won female vocalist of the year at the Tejano Music Awards, in San Antonio. Now, that was a shock, because she had come out of nowhere. She was only a teenager. But she was connecting with her fans, and that’s what it’s all about. She was young and hip, and she wasn’t playing your mom’s Tejano music.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: We actually started to dig the idea of being rock stars.

RAMÓN HERNÁNDEZ was the band’s first publicist. He is the founder and curator of the Hispanic Entertainment Archives, in San Antonio. The band had a hunger to succeed, and their songs were pretty creative. I remember when they came out with “La Bamba,” which Ritchie Valens had recorded in ’58, and they did it salsa-style. The first week it was released, it immediately came in at number sixteen as a Power Pick on Billboard’s Hot Latin 50. That was the band’s first hit on the national charts.

“It was, like, Selenamania.”

When she was seventeen, Selena signed a one-year contract with Coca-Cola for $75,000 and was featured in English- and Spanish-language ad campaigns in Hispanic media markets across the country. Thanks to the growing popularity of the band and other Tejano acts, like La Mafia, Mazz, and Emilio, major record labels like EMI and Arista came to Texas to get in on the action, co-opting a once obscure regional genre. In 1988 backup singer Pete Astudillo joined Selena y Los Dinos and began collaborating with A.B. on a more danceable, cumbia-inspired sound that drew on elements of funk and hip-hop. The following year, a guitarist from San Antonio named Chris Perez joined the group as well, and soon band members were speculating about a romance between him and Selena.

YVONNE “BONNIE” GARCÍA: I first saw Selena perform at the Tejano Music Awards in 1987, and she was a showstopper. She had the entire audience on its feet. She took command of that stage like she had been there forever, working it from one side to the other with those signature moves. Her whole persona—her smile, her energy, her charisma—was so appealing. I was sitting there thinking, “Okay, I’m in charge of Hispanic marketing for Coca-Cola, and this is a phenomenal talent. I’ve got to talk to this girl.”

PETE ASTUDILLO co-wrote some of the band’s biggest hits, including “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and “Amor Prohibido.” He is the lead singer of the rock en español band Ruido Añejo and lives in Laredo. There was never a dull moment when she jumped onstage. Her dancing ability was incredible, and she could really sing. She sang with a lot of emotion, which really moved people. After a concert, she would stay for hours, signing autographs and visiting with her fans.

MANUEL PEÑA, an ethnomusicologist, is the author of Música Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation. He lives in Fresno, California. Selena, I think, represented the collective aspirations of many Mexican Americans. She came from the barrio, and so people identified with her, especially women. She symbolized what was possible, but she was down-to-earth. The one time I met her backstage, there was no artifice there at all. She was just a very likable person—approachable and genuine and unassuming. As a deejay once said about her, “She still ate tortillas and frijoles.”

JOSÉ BEHAR was the president and CEO of EMI Latin. He is now the CEO of Diara LLC, a holding company that owns interests in emerging music and fashion ventures. He lives in Los Angeles. I signed Selena y Los Dinos on the basis of one performance. A colleague and I saw her at the 1989 Tejano Music Awards, and I immediately knew there was something magical about her. She was seventeen, and she already knew how to captivate a crowd.

CAMILLE ROJAS was a deejay at KRIO in San Antonio. She is now a massage therapist in Katy. People thought she had a beautiful figure. Everybody would say, “¡Qué cuerpazo!” which means, “What a body!” But Selena was just a normal girl with the same apprehensions we all have. She used to laugh about having a big rear end.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: This was the age of Madonna, Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul. Bustiers with black leggings, a big belt, and boots—that was the look. Selena would start off a show wearing a bustier with a denim jacket over it, and gradually she would lose the jacket. But she always kept it tasteful. She was never descarada, cheap-looking.

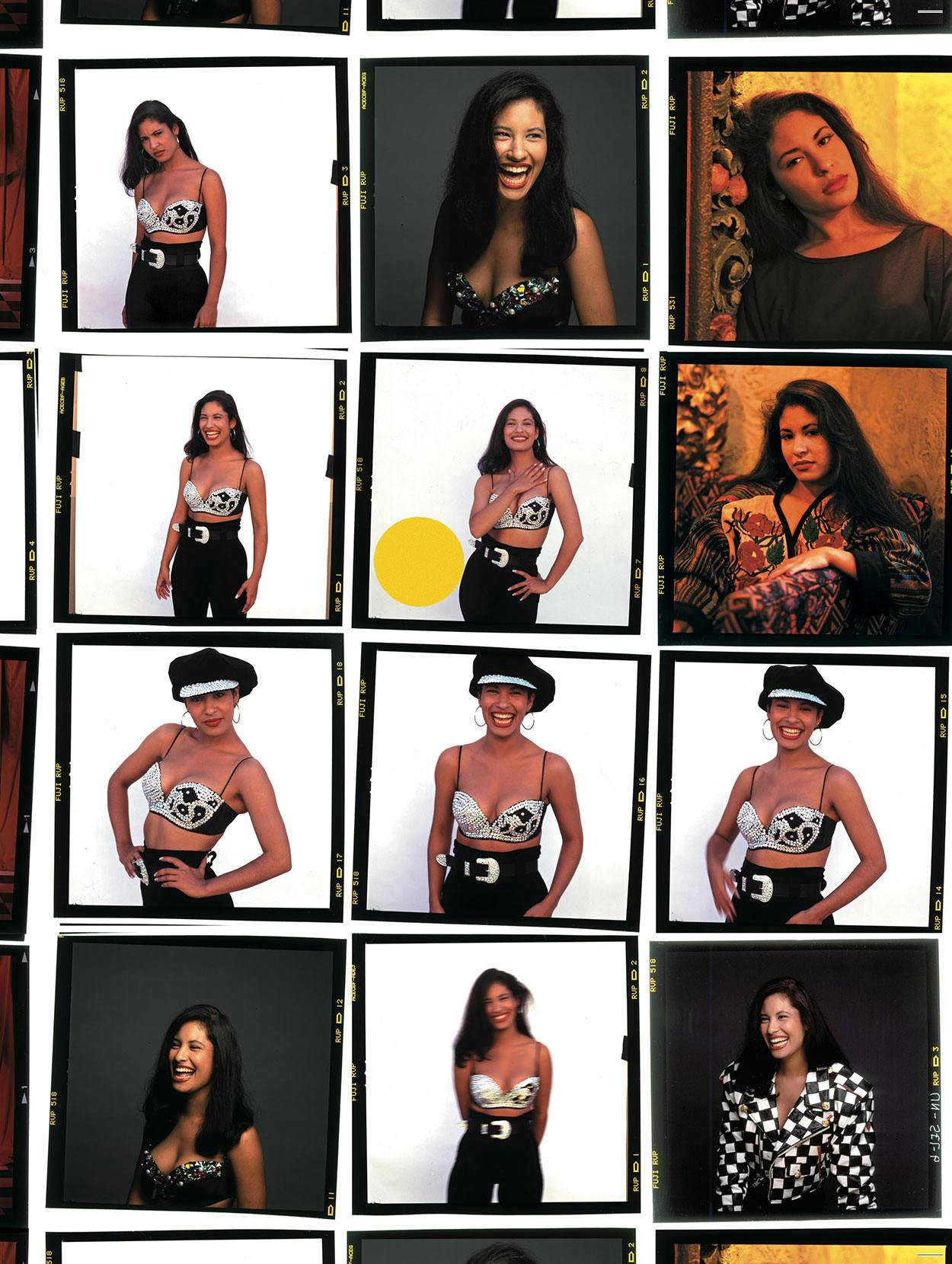

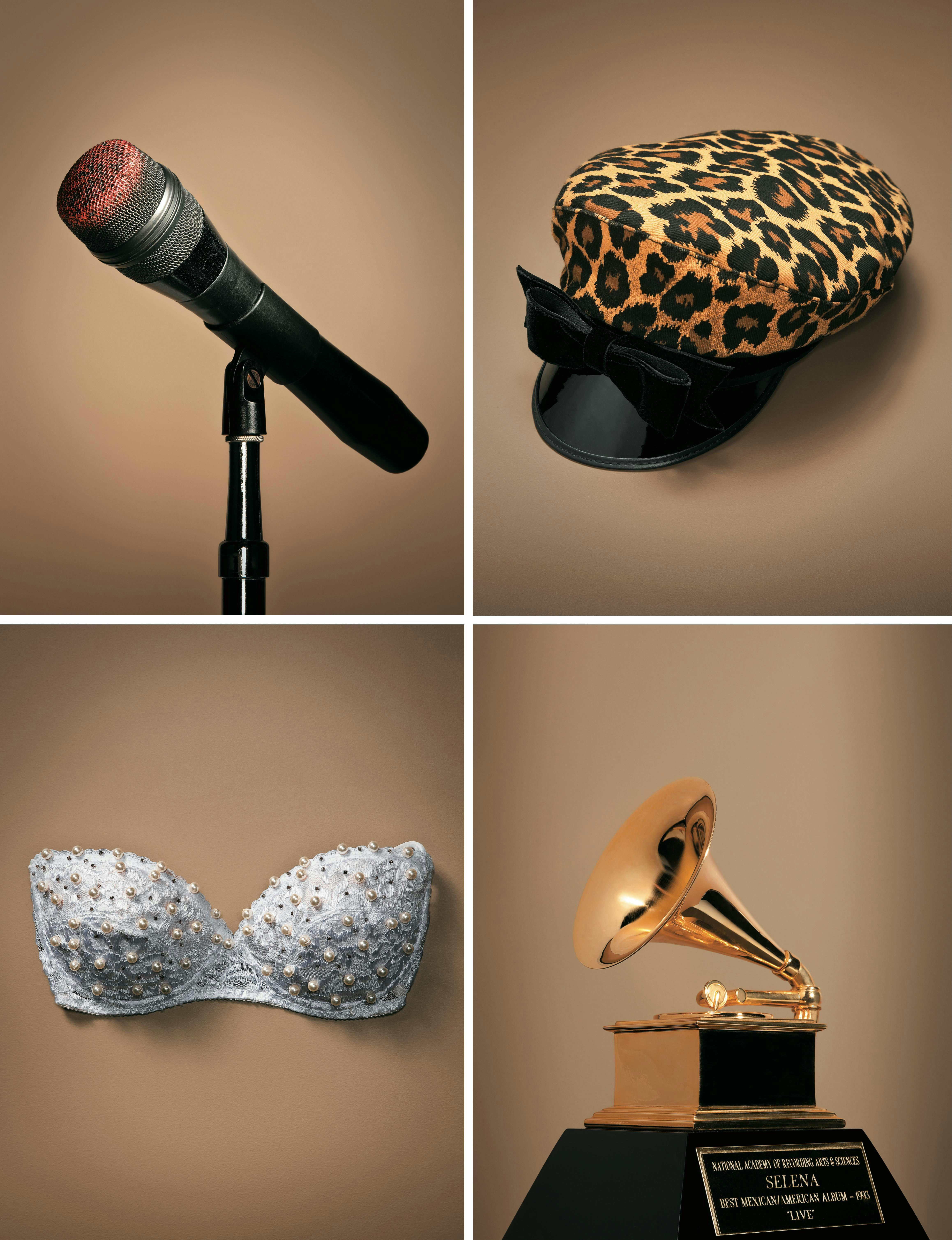

MARTIN GOMEZ was the fashion designer for Selena’s clothing line. He is now the divisional vice president of product development for Coldwater Creek, in Sandpoint, Idaho. Before we met, she used to make her own bustiers for her stage show. She would buy bras at Victoria’s Secret and glue-gun Swarovski crystals onto them.

CAMERON RANDLE: She was sexy, but she knew exactly how far to go. I think that was because you saw a combination of a young woman coming into her own, yet doing so publicly with her father in the room at all times. She had one eye focused on the audience and one eye focused on him.

JOSÉ BEHAR: I came to an important realization that didn’t go over well with Abraham. I woke up one morning and I said, “The world wants Selena; they don’t want Selena y Los Dinos.” I talked to Selena, and she got it. She knew that she had to evolve. Well, when she spoke to her dad, he went nuts. He called me and started yelling, “What, are you trying to break up the family?” I said, “No, Abraham. The band can still record with her and go on tour with her. But we need to feature Selena on the album covers and in the videos.” Abraham and I were not always on speaking terms because of disagreements like this, but once we started making Selena the focus, things really took off.

PETE ASTUDILLO: Our first hit in Mexico was “Baila Esta Cumbia,” which came out in 1990. It took a little while to catch on, but it started getting a lot of airplay in ’91, and it became a huge hit. That success in Mexico ricocheted back to the United States, and after that, our success here was tenfold. It was, like, Selenamania.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: They played an all-night concert in Monterrey with 96,000 people. Can you imagine? Before that, the biggest shows they had played were outdoor festivals with 5,000 people. There were four other artists, but the crowd wanted to see Selena. Another band would be playing, and they’d be shouting, “¡Selena! ¡Selena!”

JOSÉ BEHAR: Her Spanish was not the greatest. A reporter asked her, “¿Cómo te sientes cuando te echan piropos?” which means, “How do you feel when they throw piropos at you?” A piropo is a flirtatious compliment, like, “Hey, babe, you’re beautiful,” but she misunderstood. She thought she was being asked how she felt when fans threw bottles and cans onstage, which is customary to do when you like an artist in Mexico. So she said, “Yeah, they throw piropos and cans and flowers…” And the place just fell apart. Somebody else would have been crucified, but it was the start of a national love affair.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: In my opinion, Mexicanos have always looked down on us because we’re Tex-Mex, not Mexican. So I was amazed when they accepted her as one of their own. One Monterrey paper called her “una artista del pueblo,” an artist of the people. It even commented on the color of her skin and how it represented the masses of Mexico.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: Things were going great. And then, out of the blue, Selena told me that she liked Chris. She wanted me to talk to him, but I didn’t want to have any part in it. I knew Dad would not like it. I told her, “You’re going to get this poor guy killed!”

PETE ASTUDILLO: It’s hard to keep a secret from the rest of your band when you’re out on the road together. We weren’t 100 percent sure, but we had a feeling that something was going on between Selena and Chris. I think it was our keyboard player who told him, “I don’t know what you’re doing, dude. Abraham is not going to like this.”

CHRIS PEREZ is a guitarist in the Grammy Award–winning Chris Perez Band. He lives in San Antonio. I want to say that we were in Laredo when we had our conversation about how we both felt the same way about each other. Selena had the biggest smile on her face when we were walking back to the bus afterward. I’m smiling right now just thinking about it. I wanted to tell her, “Hey, quit smiling! You’re going to give it away.”

RUBEN CUBILLOS: Few people actually knew they were in a relationship. Chris was a cool guy; he had the long hair and played guitar, but he didn’t call a lot of attention to himself. He was reserved, not overbearing or jealous or macho the way some guys might have been. He sat back and let Selena do her thing.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: They kept things quiet for a long time. When I started having my suspicions, I told them, “I’m not involved, and if Dad asks me, I’m going to say I don’t know anything.”

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I didn’t realize what was going on until we were coming home one time from McAllen and I saw them hugging. I stopped the bus in Harlingen at two or three o’clock in the morning and exploded. I fired Chris on the spot. I dropped him off in a Whataburger parking lot and said, “You find your way home.”

PETE ASTUDILLO: I’m not going to lie to you—that was not a fun time. Selena was very angry. But there were contracts to fulfill. The show had to go on.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I saw him as a threat. What if they got married and he pulled her out of the band? All the work we did all those years would go down the tubes.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Chris was out of the band for a while, and Selena was miserable the entire time. The tension was hard on all of us. Dad called me one day when we were back in Corpus and said, “Well, she did it. Your sister ran off and eloped.”

CHRIS PEREZ: I had jeans and a T-shirt on when we went to the courthouse. I don’t remember a lot of details, because I was kind of in shock when all this was happening. I was thinking, “Oh, my God, we’re doing this. Oh, my God, what are we doing? Oh, my God!” The next thing I knew, it was over and we had been pronounced man and wife.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: After that, I accepted him as part of the family. What else could I do? By then, I owned three houses on Bloomington Street. A.B. had the house on the left, Marcella and I lived in the middle house, and I let Selena and Chris live in the house on the right for free. Everybody had their own lives, but we were still a family.

“She had that longing to make it in the English market.”

In 1993 Selena’s Live! won a Grammy for Best Mexican American Album. The following year’s release, Amor Prohibido—which included hits like “No Me Queda Mas,” “Fotos y Recuerdos,” and “Si Una Vez”—shot up the Latin charts. Selena also began recording an English crossover album, launched her own clothing line with fashion designer Martin Gomez, and opened two boutiques. As her schedule became more demanding, she came to rely on Yolanda Saldivar, a San Antonio nurse who had founded her fan club in 1991 and was a devoted follower of the band. Shy, plain-looking, and eleven years Selena’s senior, Saldivar made herself indispensable, taking on the job of managing the boutiques and eventually becoming Selena’s confidante.

MARTIN GOMEZ: I was having lunch at the little coffee shop inside the Woolworth’s in Corpus when this beautiful creature walked in wearing a black catsuit, Chanel belt, and boots. Her hair was pulled back and she was fully made-up. She did not look like anybody I’d ever seen. She was stunning, and she had such an air of confidence and sophistication. I said, “Who is that?” The woman I was with said, “Oh, my God, that’s Selena! She’s really famous.” Well, I didn’t know who she was, but I took a napkin with me—I had never done anything like that before—and asked for her autograph.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: One of Selena’s dreams was to be a fashion designer. She had a sketchbook that she was always sketching in when we were on the road. A lot of the outfits she wore onstage were her own design. Remember the white outfit she wore at the 1994 Astrodome show? She beaded the boots before we got to Houston, but she was still sewing beads onto the bustier backstage right before the show started.

MARTIN GOMEZ: I found her personality so intriguing. She took you in. She made you feel that you were instantly her best friend. I mean, think about it. I left a great job and good money to work with a 21-year-old girl I didn’t know who wanted to create a brand! From Abraham’s perspective, she was a singer and a performer first; designing clothes was her hobby. I don’t know if he realized how invested she truly was in being a designer, but it wasn’t a hobby. Having her own fashion line was her dream.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I was worried that she was trying to do too many things and that she was going to lose her focus. I didn’t want the band to lose momentum.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: My dad kept us working hard, and that was a good thing, because it kept us grounded. He never allowed anything to go to our heads. We’d have a number one hit, and his attitude was “So what?” He’d say, “Any clown can get to number one. The question is, Can you do it again and again and again?” He set the bar high. I thank him for doing that, because we never settled. But once we got to number one, there was a lot of pressure on me as a songwriter to come up with another hit. I’d think, “What trick am I going to pull out of my hat now?” She became huge, so it was a huge responsibility.

MANUEL PEÑA: She slayed—or at least wounded—the dragon of sexism in the sense that she carved out her own path in a very male-dominated market. Female Tejano artists always played second fiddle to the men, but with Selena it was, ‘Hey, here I am, cabrones!”

DEBORAH PAREDEZ is the associate director of the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the Performance of Memory. Unlike most Latina celebrities, she was morena—dark—and she did not conform to Anglo standards of beauty. She had curves, brown skin, and black hair that had not been lightened. She resonated with her fans not only because she shared the same class and regional affiliations as them but because she looked like them too.

NINA DIAZ is the lead singer in the alternative rock band Girl in a Coma, which is releasing a cover of Selena’s “Si Una Vez” this spring. She lives in San Antonio. When I was a little girl and we had sleepovers, we always had Selena contests. We would put on a little bit of makeup and hike our shirts up as much as we could without getting into trouble, and then we would see who could do her moves the best.

NANCY BRENNAN was the vice president of A&R at EMI. She is now a real estate agent in New York City. Selena was a phenomenon, but beyond her audience, she was completely unknown. She and I had dinner one night at a very chichi restaurant in Los Angeles, and no one had any idea who she was. All of a sudden, all the guys came out of the kitchen—the cooks, the busboys, everybody—and crowded around her. They were all holding napkins and asking for her autograph.

ERNEST GARZA worked security at many of Selena’s performances. He is now a hotel security guard in San Antonio. The venues were getting bigger and the crowds were getting bigger, and it was exciting, but it was scary too. Everyone wanted to get near her, to touch her. We had some crazy fans who would grab her clothes and pull her hair.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Selena brought a camera to the Grammys so she could take pictures of the stars. She didn’t understand that she was a star! I’ll never forget those words: “The Grammy goes to . . . Live! Selena!” We were screaming at the top of our lungs. I remember when we left Radio City Music Hall we heard people shouting her name outside. She turned around, in complete shock, and said to me, “They know me?” Then she turned back around and tried to be all cool, waving at them like Miss America. She laughed and whispered to me, “Wouldn’t it be embarrassing if I fell right now?”

CAMILLE ROJAS: You got the sense that she felt really lucky to be where she was and that she didn’t take anything for granted. I remember being with her backstage at a few concerts, and she always peeked out at the crowd before she went on. She’d get giddy when she saw how many people were out there. For her, it was all still a big deal.

JOHNNY CANALES has been called the Dick Clark of border music. He is the host of the long-running TV variety program The Johnny Canales Show and lives in Corpus Christi. The first time Selena performed on my show, when she was thirteen, she whispered to me, “Let’s do the interview in English!” But the last time she came on, in ’94, she spoke 100-percent-perfect Spanish. She had worked hard to really learn the language.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: I never thought I’d see the day when a Selena album would bump a Gloria Estefan album out of the number one position on the Billboard Latin charts, but that’s what happened. Gloria had been in that position forever with Mi Tierra, and then boom! Selena flew into that spot with Amor Prohibido. There were at least seven hits off that album. I knew she was ready to explode out of the Latin market.

JOSÉ BEHAR: Very few Latin artists had ever been offered a major-label crossover deal. It was Julio Iglesias, Gloria Estefan, and Selena—in that order. And with Selena, it was an uphill battle for years. I had colleagues at EMI from Latin America, the U.S., and Spain who told me, “I don’t know what you see in her,” and “She’ll never make it outside Texas.”

NANCY BRENNAN: Selena was just as American as you or me, so she had that longing to make it in the English market. English was her first language! The problem was getting her into the studio. I had never worked with anyone before who literally didn’t have time to make their debut album. How could I tell her, “You can’t play the Astrodome for sixty thousand people because we need to work on your record”?

CELIA MACIAS was Selena’s manicurist and worked in her Corpus Christi boutique, Selena Etc. She is a stylist in Corpus Christi. Selena had so much going on: her crossover album, her concerts, her endorsements, her clothing line, her boutiques. She was blowing up! She was so preoccupied with so many things that she needed somebody to make sure that everything was being run properly. That’s when Yolanda stepped into her life and made it seem like she was taking care of everything.

CHRIS PEREZ: She became a friend of the band, and we let her into our circle.

PETE ASTUDILLO: Yolanda seemed sincere. She was president of the fan club, and we thought she loved Selena and the band. To win Abraham over is a big deal, and she did. She won all of us over. She threw us parties and traveled with us to awards shows. She wasn’t just a kid who wanted to hang out; she was older than us and she was a professional, and she seemed to genuinely want to help Selena in any way that she could.

MARTIN GOMEZ: My first impression of Yolanda was that she was very sweet, like a mother figure. You know the kind of person who is so caring that she’s almost suffocating? She used to mother me and ask, “Do you need anything, m’ijo?”

AL RENDON is a photographer in San Antonio who worked with the band extensively. Yolanda gained a lot of importance in Selena’s life. Whether Selena realized it or not, Yolanda became her filter.

CELIA MACIAS: When I started off at the store, Selena had lots of friends working for her. Once Yolanda came on board, she got rid of Selena’s friends one by one. Anyone who captured Selena’s attention, she eliminated.

MARTIN GOMEZ: Yolanda tried to limit my time with Selena, which was very difficult, because we were creating a brand and we needed to communicate about her vision. She clearly wanted me out of the picture. When we were fitting models for our San Antonio fashion show, weird things started happening. Threads were cut. Hems were pulled out. Buttons fell off a denim outfit that Selena tried on. Selena got very frustrated with me and said, “Martin, what’s going on?”

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: I wasn’t running Selena’s business. I was so busy with the band that I didn’t realize what a problem Yolanda had become until it was too late.

MARTIN GOMEZ: One of my seamstresses told me that she had gone to pick up some zippers at Yolanda’s house and that her house was covered wall-to-wall with Selena photos. I even noticed Yolanda following me home one time. It all got a little spooky.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: My sister was very trusting and naive, really. My brother and I were that way too. My dad was so protective of us growing up—and there is good and bad in that—but the way we were raised, we tended to think everybody had a good heart.

MARTIN GOMEZ: Yolanda and I had a huge falling-out, and I told Selena that I had to leave, even though I still had a few months left on my contract. It was very emotional for both of us, and there were a lot of tears. Selena felt really bad about the situation, and the last time we spoke, she said, “I’m so sorry.” I told her, “You have nothing to be sorry about. Just be very, very careful.” I thought Yolanda was obsessed with her, and I told her that I was really concerned. Selena said, “Oh, Martin, you worry too much.”

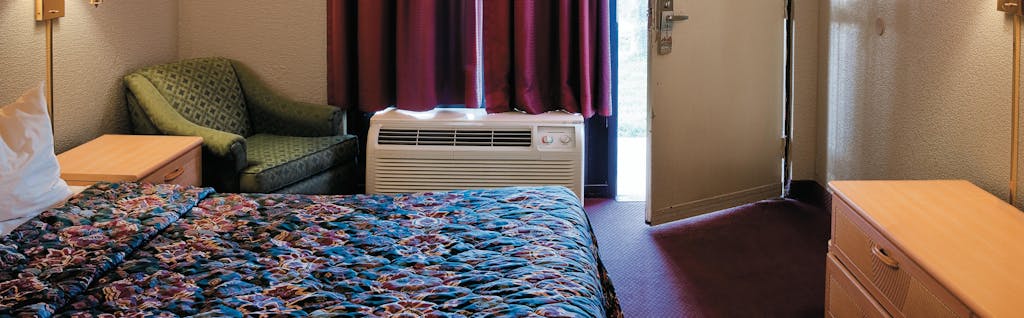

“Her last words on earth were ‘Yolanda Saldivar, in room 158.’ ”

After Gomez’s departure, in early 1995, questions began to arise about Saldivar’s bookkeeping for the fan club and the boutiques. In March, Abraham confronted her about accounting discrepancies he had discovered and warned her that he planned to call the police. Saldivar, in turn, purchased a .38-caliber snub-nosed pistol and pleaded with Selena to meet with her privately at the Days Inn in Corpus Christi, where she was staying. She promised to hand over paperwork that Selena needed to file her upcoming tax returns.

CELIA MACIAS: Selena came into the store to get ready for her anniversary, and I was doing her nails when she started receiving phone calls from Yolanda. Her nails were still wet, so I held her phone up to her ear. Selena was asking Yolanda to explain things: Why hadn’t her fans received things they had been promised? Why was there money that was unaccounted for? That’s when things escalated. Yolanda started freaking out and telling her all these lies, claiming that she had been abducted in Mexico. She was crying really loudly and slurring her words, and she said that she wanted Selena to meet with her.

CARLOS VALDEZ: They agreed to meet at the Days Inn, but Chris came with her, so Yolanda didn’t get a chance to talk to Selena alone. The next morning, Yolanda called her and said, “I didn’t want to tell you this, but I was raped when I was in Mexico, and I need your help.” Selena took her to the hospital, where it was determined that Yolanda hadn’t been raped.

CHRIS PEREZ: I had no idea that she was going to pick up Yolanda and take her to the hospital. She got up before me and didn’t tell me where she was going.

CARLOS VALDEZ: Selena took her back to the hotel, and they had an argument in Yolanda’s room. Selena had her back turned—she was probably turning to leave—when Yolanda raised the gun and shot her in the back. Selena started running, and she ran about 130 yards across the parking lot to the lobby, screaming. Yolanda came out of the room with the gun still in her hand, and several witnesses later testified that she looked like she was going to shoot again. Selena ran into the lobby soaked in blood, and before she passed out, she said, “Lock the door! She will shoot me again!” One of the hotel employees, Ruben DeLeon, kneeled beside her and managed to wake her up. He asked her, “Ma’am, who shot you?” The last words she said—her last words on earth—were “Yolanda Saldivar, in room 158.”

RICHARD FREDRICKSON was a Corpus Christi Fire Department paramedic. He still works at the department as a self-contained-breathing-apparatus technician. We put her in the back of the ambulance and started doing CPR and tried to get an IV started. She was not responsive; she had no pulse. The bullet had hit an artery, and she had lost a lot of blood. While I was trying to find a vein for the IV, her right hand opened and a ring fell out. Apparently she had been clenching the ring in the palm of her hand that whole time.

PHILLIP RANDOLPH was the owner of Phillip Randolph Jewelry, in Corpus Christi. He is now a jewelry designer at Aucoin Hart Jewelers, outside New Orleans. Yolanda had me design a ring for Selena. It was a fourteen-karat gold ring topped with a white-gold egg, encrusted with 52 diamonds. The letter S was incorporated into the band design three times on each side. She paid the balance with Selena’s company card and asked that I not tell Selena how it was paid for.

CARLOS VALDEZ: This was a friendship ring that Selena had been wearing, and Selena took it off during their argument. I think that’s what set Yolanda off. She knew that once Selena walked out of that room her world was over. She would either go back to being a nobody, or she would go to prison for embezzlement. She was furious at Mr. Quintanilla for accusing her of stealing from the business, because that had turned Selena against her, so she did what she knew would hurt him the most.

LOUIS ELKINS was the cardiothoracic surgeon on call that morning at Memorial Medical Center in Corpus Christi. He is now in private practice in Mountain Home, Arkansas. When I arrived in the ER, she had no pulse and no blood pressure and no heartbeat. The subclavian artery had been severed, so she had lost a tremendous amount of blood. We ran the resuscitation as long as we could, but it came to a point where it was futile to keep going. Once I was convinced that we had done everything that could possibly be done, we made the decision to stop all resuscitative efforts. It was 1:05 p.m.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: My brother left the hospital before she was pronounced dead because he said he knew; he felt it, and he had to go. I remember my mother crying and my dad breaking down, and I don’t remember too much after that. Honestly, for the next two years of my life I don’t remember much of anything. I was lost, lost, lost.

CELIA MACIAS: There was a huge crowd outside the hospital, and everyone was crying. The main entrance to the hospital was shut down. It was just crazy, people everywhere.

CAMILLE ROJAS: I had just left the radio station and was driving home after my shift when I heard the news broadcast on the radio. I tried calling Yolanda—at that point, I didn’t know she was involved—and I remember it going straight to voice mail.

MARTIN GOMEZ: I will never forget hearing the announcement on the radio: “This is not an April Fools’ joke. Selena Quintanilla Perez has died.” I lost it. I remember not going to work the next day and getting really drunk. My wife found me on the kitchen floor, sobbing.

JOE NICK PATOSKI: I went to the Days Inn two days after the shooting, and there were a lot of people milling around with dazed expressions on their faces. One guy had hitchhiked from Michigan; he put his thumb out as soon as he had heard the news and arrived at the Days Inn that morning. The doorway to the room where Selena was shot had been turned into a shrine, and people were retracing her steps from the room to the motel office. I remember it was very quiet and nobody was talking. There were people on their hands and knees in the Saint Augustine grass, looking for blood, mementos, anything, trying to make sense of it all.

“We couldn’t believe a brown girl could be so famous.”

After the shooting, Saldivar sat in her pickup outside the Days Inn and held the gun to her head, keeping police at bay for nine and a half hours. Before surrendering, at 9:35 p.m., she blamed her actions on Abraham, telling negotiators, “Her father hates me. Her father is responsible for this.” (Saldivar declined to be interviewed for this story.) Her trial, which was held in Houston that October, ended in a guilty verdict. Saldivar is now serving a life sentence for murder with a deadly weapon at the Mountain View Unit, in Gatesville, where she is kept in protective custody due to the notoriety of her case. By order of the trial judge, the .38 that she used to kill Selena was cut into fifty pieces and scattered across Corpus Christi Bay.

ABRAHAM QUINTANILLA: We had to move after her death. We could hardly leave the house for the first few weeks because of the crowds outside. Months afterward, there were still people standing outside the house, even in the middle of the night. I’m not talking about one or two people. I’m talking about fifteen or twenty, there in the street, all the time, even at three o’clock in the morning.

RAMIRO BURR: It was like a daily series of shocks. I’d been on the beat by that time for almost fifteen years, and yet I underestimated what she meant to people and how fully they felt connected to her. Her albums went platinum after her death, and Dreaming of You came out a few months later and instantly went to number one. And then she stayed in the news continuously because of the investigation and the trial. The fascination with her just did not stop. I remember reading an AP story months after she died about how there was a big spike in the number of baby girls being named Selena.

NANCY BRENNAN: She was the first Latin artist to debut on the Billboard charts at number one. Of course, the buildup—the media attention to this horrible situation—meant that everybody was anticipating this release. There were supposed to be fourteen tracks, but we had only recorded four of them, so we put together a tribute album of new and old songs. Making that album was the most difficult thing I have ever had to do, because we were listening to her voice all day and crying as we were mixing the songs.

SUZETTE QUINTANILLA ARRIAGA: Everybody deals with grief differently. I used to get out all my photos and open up my sister’s traveling makeup case so I could smell her. I took over the boutiques because I knew Selena would have wanted to keep them going, but it was traumatic. All day, every day, people came into the store to tell me how much they loved my sister, and sometimes I had to go into the back and just cry and cry. To this day, my mother doesn’t talk publicly about what happened. Chris kind of shut down. He left everything in the house exactly as it was the day she died. Dad consumed himself with work. My mother told me once, “Your father cries in the shower because he doesn’t want me to know he’s crying. He thinks I can’t hear him, but I can.”

CHRIS PEREZ: My marriage was over, my band was over. We had talked about having kids while we were still young, but that was over. Everything ended, just like that.

A. B. QUINTANILLA: Nothing will ever be the same as sharing the stage with my sister. When we performed in Central America, there were times when the emotion was so overwhelming that I would start to cry. I would turn away from the crowd and act like something was wrong with the amplifier until I gathered myself. You have to understand: She was generating electricity, and I was a part of that conductor. After she passed away, I played my own music at the Astrodome. I played in Estadio Azteca, in Mexico City, for 125,000 people. But I was never able to re-create that high again. No matter how far I’ve gone with my own music, it’s never had the same flavor. It’s like food without salt.

CAMERON RANDLE: Tejano became increasingly directionless after she died. Selena had a great deal to do with driving the market, and once she was gone, there was a lot of confusion and disorientation. There was uncertainty about who would carry the mantle going forward, and Tejano never really recovered.

DEBORAH PAREDEZ: People magazine did a split cover when she died, with Selena on newsstands in the Southwest and the cast of Friends on newsstands in the rest of the country. The Selena issue sold out, as did multiple reprintings of the issue. As a result, People produced a tribute issue. It was only the third time in the magazine’s history that a tribute issue had been produced; previous ones were for Jackie Kennedy Onassis and Audrey Hepburn. The tribute issue and subsequent printings sold out, and that’s how People en Español came about. There was a realization in the publishing industry that there was a whole Latino market out there that mainstream culture had been overlooking.

RENA DEARMAN: Anglo friends of mine would tell me, “I didn’t know anything about Selena until she died, and now I listen to her music and I love it.” They would sing her songs, and they had no idea what they were singing, but they loved her music. I was glad that everyone finally knew what I had known all along, but it was also bittersweet.

DEBORAH PAREDEZ: After her death, I think some Latinos were surprised to discover that she had touched so many lives beyond their community. Part of that may be due to our own internalized racism; we couldn’t believe a brown girl could be so famous. Dark-skinned Latinos are certainly not embraced by popular culture very often. And among Tejanos, we thought of Selena as one of our own. She was just like us; she was our girl. When you’re Tejano, you’re keenly aware of the hierarchy of Latinos, and Tejanos are the least cool in that hierarchy. We’re the blue-collar country bumpkins. So to see her embraced by a range of Latinos was profound.

MARTIN GOMEZ: Selena was the first person who made me proud to be Mexican. Before Selena, I was more embarrassed than proud, to be honest. The sense of pride she had about where she came from was new to me, because I had pretty much grown up in an all-white world. The music and the world that Selena created all made me extremely proud of where I came from, and I started thinking of myself as Mexican American.

KEREN SMITH is Selena’s first cousin and lives in Selena’s old house. Fans drive by on a daily basis. They drive by real slowly, staring. Some do a U-turn at the end of the street and drive past the house several times, and then they stop to take pictures. Many of them have traveled from far away, so they want to get a good look before they leave.

ANTONIO ZAVALETA is a scholar of folk religion. He is a professor of anthropology and the special assistant to the provost at the University of Texas at Brownsville. There is a long tradition in Latino culture of designating folk heroes, like Pancho Villa or El Niño Fidencio, as folk saints, or santos populares. In death, Selena is emerging as one of these revered folk saints. The living and the suffering believe they can ask the spirit of Selena—which is most certainly in heaven, having been martyred—to intercede with the Mother of God on their behalf for the delivery of a miracle, such as bringing a wayward daughter home.

CELIA MACIAS: There isn’t a day that goes by that there aren’t people out there visiting her memorial. I work right around the corner, so sometimes I go and have lunch with her. If I get five minutes alone with her, that’s unusual. Someone will bring flowers or take her picture or pay their respects. Once, I met three teenage girls from the Netherlands there who had spent five years saving up money so they could visit Selena’s hometown. Some days I sit there and think, “Oh, girl, I wish you were here to see all this.”

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Selena

- Corpus Christi