The first film studios arrived in Texas sometime around 1910, when the brother of famous French director Georges Méliès set up the Star Film Ranch, near San Antonio. Sunny weather and wide-open spaces kept filmmakers coming. The movie Wings, which was awarded Best Picture at the first Academy Awards, in 1929, was shot at an airfield a few miles from the Méliès property. Since then, films and television shows—from Giant to Dallas to Slacker—have been some of the most important ways the state tells the story of itself.

Brian Gannon, the director of the Austin Film Commission, likens the Texas film business to ranching and oil, something that’s integral to to the state’s profile on the world stage. “It’s a heritage industry,” he says. Gannon grew up in Ireland, where his parents made sure to watch Dallas every weekend. His office fields calls from Scottish and Japanese tourists wanting to know where the television show Friday Night Lights was filmed.

But the industry isn’t immune to threat, and in the past few years, the most implacable foe of the state’s filmmaking business has been one of its own creation: the Mongolian death worm, a fearsome burrowing monster that lurked in the steppes near Genghis Khan’s tomb until it was unleashed by an ill-advised fracking operation and began wreaking havoc. At least that’s the plot of an obscure 2010 sci-fi B movie, Mongolian Death Worm. Because the film was shot in Dallas and the producers were able to certify that they used a mostly Texan cast and crew, it received a tax rebate of about $47,000 from the Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program.

That’s a small investment compared with the overall size of the program’s fund, but it was enough to give the program’s opponents a potent symbol of what they see as government waste. This year, as the Legislature decided whether the film incentive program should be defunded and shut down, the worm returned, as it has during nearly every discussion about the program since 2015.

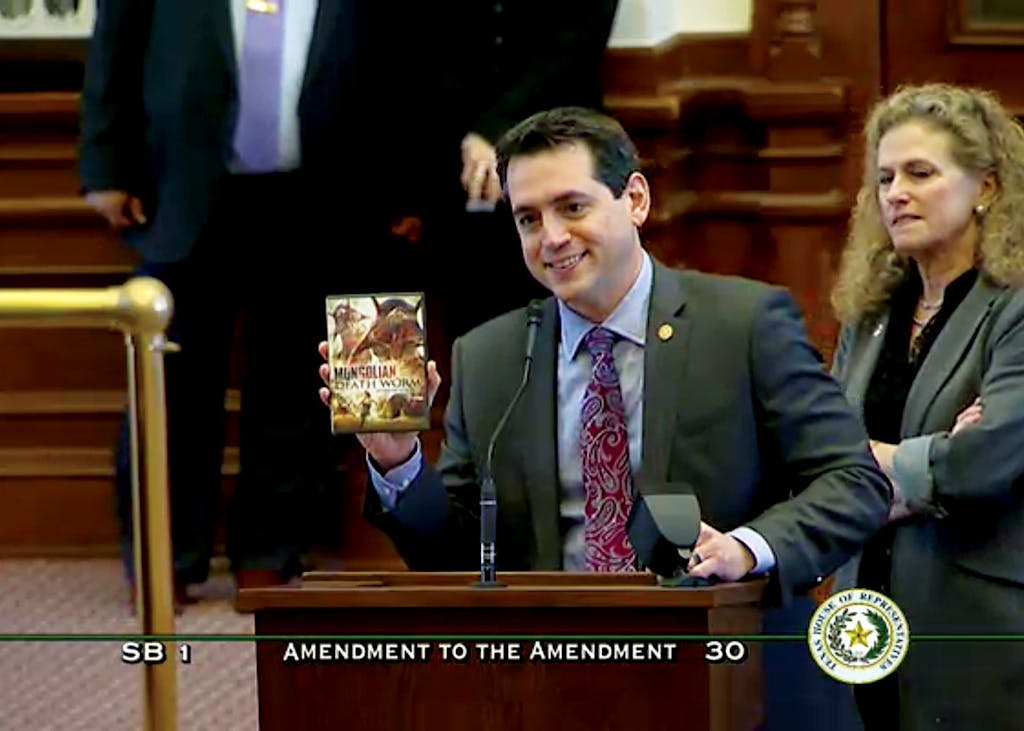

It happened on April 6, during a seventeen-hour debate in the House about the state budget. Representative Matt Shaheen, a Republican from Plano, has slammed assistance for the film industry in the past as a giveaway to “polarizing” figures such as Sean Penn and Matt Damon. After Shaheen introduced his amendment to defund the incentive program, Republican representative Matt Rinaldi, from Irving, rose from his seat and walked to the back mic with a prop in hand. “I’ve gotten from Representative [Dan] Huberty’s office a copy of Mongolian Death Worm,” he said, hoisting a DVD case into the air to provide the audience a view of the worm’s gaping maw. “Don’t you think that fifty thousand dollars would have been better spent elsewhere?”

Shaheen and Rinaldi knew their audience. The amendment sailed through along party lines; not a single Republican lawmaker voted to keep the incentives in place. Since the Senate’s version of the budget had also defunded the program to almost zero, the House vote, in the manner of an end-of-episode cliffhanger, put the state’s creative industries into an immediate panic.

Government incentives are a relatively new way of doing business in the film industry. In the past, producers chose shoot locations for the same practical reasons they always had: the availability of good weather, good crews, and low costs. But just before the turn of the millennium, the look of American film started to change. “Every movie had pine trees in them, because they were filmed in Vancouver,” says Gannon.

American production companies had long headed north largely because of cheaper costs, but it wasn’t until the mid-nineties, when the Canadian government started paying companies to do so, that lawmakers in the United States recognized the potential for a huge economic loss. In 2002 Louisiana became the first state to offer incentives, and it soon became clear that the industry would relocate at startling speed from any place that didn’t. The states that offered the most incentives grew local industries almost overnight, and in the past ten years, a substantial number of TV shows and movies have been filmed or set in Louisiana, New Mexico, and Georgia. Waco, a prestige miniseries about the Branch Davidians, is filming in Santa Fe this year; the first two seasons of the cable series Halt and Catch Fire, which were set in eighties-era Dallas, were made in Atlanta; and Hell or High Water, last year’s Oscar-nominated film about two bank-robbing brothers in Texas, was shot in New Mexico.

“In the early days, like when I was making Dazed and Confused, there weren’t incentives anywhere, and our industry was growing here,” says director Richard Linklater. “Robert [Rodriguez] moved back to Austin and started productions here. Mike Judge moved here. So we were climbing up on our own, doing pretty well. It was an exciting time. But when incentives started appearing in other states, things started dropping steadily. It reached sort of a crisis.”

The answer to that crisis, the Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program, wasn’t controversial at its inception, in 2005. The process is fairly cut and dried. Each session, the Legislature injects money into an account, which is dispersed until it’s empty. If a project meets criteria that have been set by the Texas Film Commission, filmmakers, television producers, and even video game developers can submit receipts for money they’ve spent in Texas and get back a small portion.

The program was funded meaningfully for the first time in 2007, to the tune of $22 million, with support from lawmakers of both parties. The funding nearly tripled in 2009, and reached a peak of $95 million in 2013. A report that examined Austin-area projects, prepared by the Texas Film Commission, suggests a strong correlation between the size of the rebate fund and industry activity. For the 2010–2011 biennium, the commission paid out $23 million in rebates for projects that created $155 million in in-state spending. Those numbers dipped slightly to $19 million in rebates and $121 million in economic activity in 2012–2013 before jumping to $55 million and $284 million in the next biennium.

Advocates for the program, like the Texas Motion Picture Alliance, say that the money it generates goes directly into the pockets of Texans and Texas companies, most of them small businesses, at a ratio of about $5.55 for every $1 spent. These results were real enough for the town of Pittsburg, population of about 4,500, to put together its own incentive program after a single low-budget film shoot—2011’s Humans vs. Zombies—brought money to the town’s businesses. “They come in and eat at our local restaurants, stay at our hotels, buy gas at our gas stations, buy supplies at our local hardware stores,” said Amanda McCellon, who runs the community development program for the Pittsburg Economic Development Corporation. “The money that we gave came back to us two- or threefold.”

Critics, who include most of the Legislature’s more conservative lawmakers, as well as influential groups like the right-leaning Texas Public Policy Foundation, argue that any economic benefit is short-term because film shoots will leave when the project is completed. Worse still, in their eyes, the program is tainted by association with former governor Rick Perry’s flagship corporate incentives programs, which became a symbol of cronyism for conservatives allied with the tea party revolution. And it doesn’t help that incentives are perceived as a giveaway to Hollywood, which is in California, a state Texas Republicans loathe, and film-centric Austin, a city that fares barely better in their estimation.

The Texas program has always been small compared with other states—California spends $330 million a year, and at one point Louisiana spent $250 million—but in 2015, the Legislature cut the money allotted for Texas rebates back to $32 million for the biennium, making the state an even dicier proposition for major investments. Still, filmmakers like Linklater have managed to leverage that state funding when negotiating with financiers who might be leery of shooting in Texas. But these days, Linklater says, even he’s losing that argument. “I’ve been shooting two movies in Pennsylvania recently, the first time I’ve ever left the state [for incentive reasons],” he says. “It’s really sad for me, but that’s just personal. It’s most sad for me to see friends and crew moving to Atlanta.”

Among those thinking about relocating is Phil Schriber, a fifth-generation Texan who runs Film Fleet, a Pflugerville-based transportation and logistics company that owns some 250 trucks, trailers, and mobile generators that are rented to productions all over Texas and as far away as Chicago. “We had a very, very good March,” he says. He’s standing in the parking lot of his depot, which is typically almost empty. Then April came, and Shaheen’s amendment, and everything shut down. Nearly all his trucks returned. “All these shows are wanting to come back to Texas. But the finance people aren’t gonna let them do it unless there’s an incentive here,” he says. If the incentives aren’t revived, he’ll have to permanently move equipment, and potentially his business, out of the state.

When the rebate program began, lawmakers had people like Schriber in mind, says Linklater, who’s been lobbying for it since its inception. “When we were just getting this bill going, you could actually go meet with [Lieutenant Governor David] Dewhurst, Rick Perry, those guys, and they were all about jobs. They loved the program,” he says. Then the program’s Republican backers started to lose their primary races. “On the way out the door, one of our supporters said, ‘Good luck with these new guys. I’m a conservative, but these guys are crazy.’ ”

Earlier this year, the Lege offered to honor Linklater on the floor of the House, which it has done a few times. But this session felt different to him. “I thought, you know what? No, I don’t think I’m gonna do that.”

When lawmakers voted in April to cut funding for the film rebate program, they were performing, as politicians do. Railing against Hollywood pleases the activists who support lawmakers like Rinaldi and Shaheen. Saving taxpayers from the next Mongolian Death Worm is a great thing to put on a mailer. But lawmakers were also free to support defunding the program, in part, because Shaheen’s budget amendment was mostly for show; the ultimate fate of these programs is decided during the final closed-door budget negotiations between the House and Senate, which involve only a few key senators and representatives, so no one has to take an unpopular vote.

And the program actually has high-profile support, from Governor Greg Abbott—who even asked for a funding increase, to $72 million a year—and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. The Texas Film Commission is controlled by the governor, and governors are always loath to give up any influence. And Patrick is a proud entertainer, a TV and radio vet who produced a feature documentary, The Heart of Texas, shot near what was then his senate district.

But the industry can’t make plans based on the predictions of Capitol insiders. The debate every two years about the program’s continued existence incurs its own collateral damage. In states where the incentives are assured, Gannon says, studios build permanent facilities and soundstages. Commitments made in Texas are more short-term. In March, some of Schriber’s trucks were rented by the company producing a pilot for a new Marvel television show, Gifted. It was shot in North Texas—home to both Shaheen and Rinaldi—and the area stood to benefit from Marvel’s healthy budgets if the show was picked up for a full season. But time ran out. On May 24, with the question of the incentive program still unresolved at the Legislature, the Dallas Film Commission announced that the show’s first season would be shooting elsewhere.

A few days later, the budget conferees emerged with the news that the program would be funded after all, albeit at $22 million for the biennium, its lowest level since 2007. “I am certainly grateful the program has funding,” says Gannon. Though he’s disappointed with the cut, he says that film advocates are now focused on the next threat: the prospect of a transgender bathroom bill. The law, to be decided in a special session, would “be very detrimental to the film industry,” he says, and would scare off out-of-state investment. The only thing to do after that, Gannon believes, is to start planning for the next session, in 2019. “To quote Friday Night Lights,” he says, “ ‘Clear eyes, full hearts, can’t lose.’ ”

Though the Mongolian death worm will continue to stalk the Texas film industry, a more fundamental problem is that the cultures of the Legislature and the creative community are radically out of alignment. One early May afternoon, before it was clear if funding would come through, hundreds of citizen lobbyists filled the Capitol to track down lawmakers and pitch their ideas for the film industry. One small group haltingly found its way to the office of Democratic state representative Diego Bernal, of San Antonio, on the uppermost floor of the state Capitol extension, which was teeming with suits and high-dollar lobbyists. “We all work in the Texas film industry,” Chris Telles, a casting agent, said to Bernal’s legislative director. “There’s a thumb drive in this bag that has the song and dance about our whole song and dance.”

By the standards of the Lege, this was an unusual group. Among them was Telles, a charismatic El Pasoan with long hair and black-rimmed glasses, who took the lead; a stage mom with her seven-year-old daughter, hoping for more auditions closer to home; a film critic in a T-shirt and iridescent baseball hat; an actress who related that she’d been in the Screen Actors Guild “since I was young” and who wanted her film-industry son to be able to come home from L.A.; and a gruff crew member in a plaid shirt who said he’d rather retire than move back to Atlanta, where the film business is thriving but conditions for crew members aren’t ideal.

The group moved on to Democratic state representative Victoria Neave. The office was empty, except for a stressed-looking staffer standing against a back corner. Again, Telles talked about the flash drive with “the song and dance.” The staffer stepped away to take a phone call, and the group stood around in silence. Christina Romero, one of the actresses in the group, pointed to a pro-immigrant poster on the wall.

“A lot of the filmmakers coming up at UT are Latinos, and they are getting to tell their stories through film,” she said, getting choked up. “One thing that’s really important to me is that everybody has a voice, and that everybody gets to tell their story. Film is a place where that happens. Film is a place where I got to be liberated.” It’s a place that took her to New York and London and L.A., all the way from Denison. “And I came back here when they started the film incentive program.” She wants that experience for other marginalized young people. After a while, the staffer reentered the room. “Do you have a business card?” she asked.

The last visit of the day was to the office of state representative Lance Gooden, a Republican. The office was cold and mostly empty. A young woman sat quietly in the back, wrapped in a blanket. Another young woman, sitting by the door, fielded the pitch. “I’ll give this to my boss,” she said, emptying the bag of film knickknacks on her desk.

The group gathered one more time in the Capitol hallway. They took a picture together and parted ways. A few floors up and closer to the center of power, a government relations representative from deep-pocketed 20th Century Fox was holding quiet meetings with the governor’s staff and the members of the conference committee. At the Legislature, as on set, the most important decisions were being made offscreen.

Christopher Hooks is an Austin freelance journalist.

- More About:

- Film & TV