Refugio, Texas, 1975. Midnight. I’m babysitting a drilling rig on the Tom O’Connor ranch, trying to find a station, any station, on my ten-inch portable television. I turn the set to the west and bend the rabbit ears in opposite directions. Nothing but snow. I decide to reboot: I kick the crap out of the TV. Eureka!

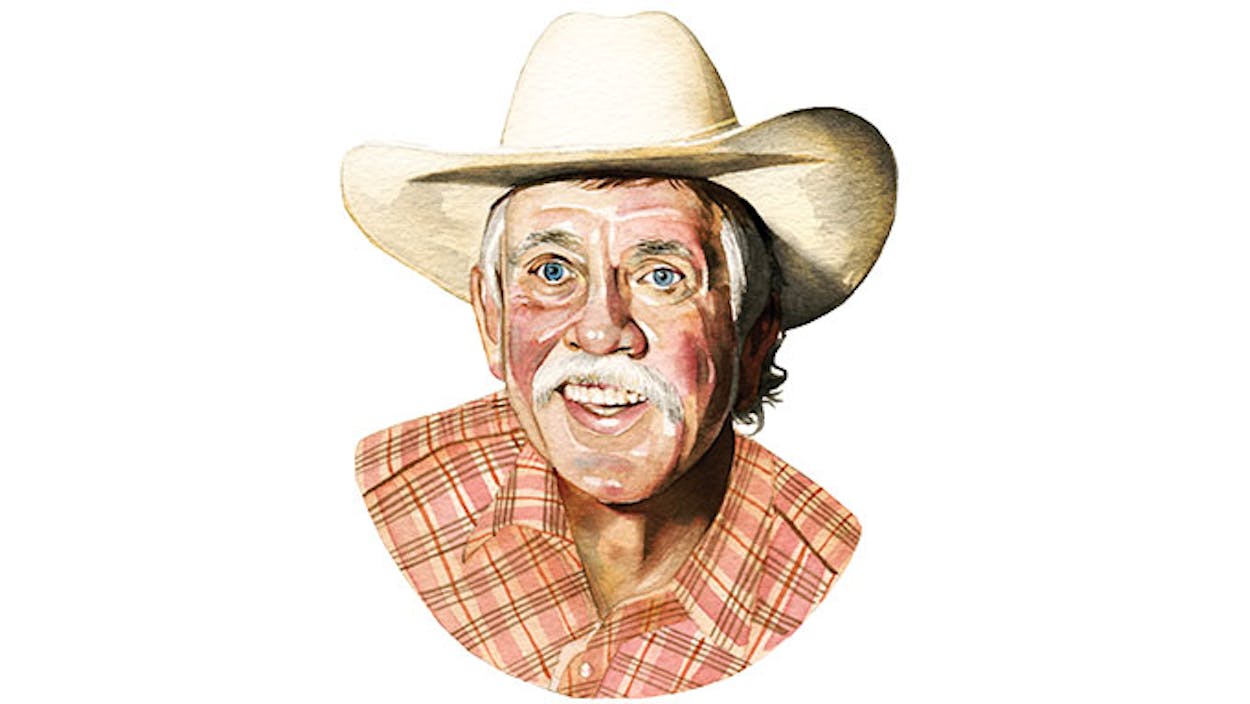

Cool. It’s a guy singing and playing the guitar. No sound? Where is the damn volume on this piece of junk? I watch the guitar slinger in silence. He has longish hair, a swooping mustache, and a white cowboy hat perched back on his head. The good guys in the old cowboy movies wore their hats this way. His big, friendly face is belting out his song as if it were last call at the Southern Baptist Convention. I find the volume knob as he’s introducing his final song. The troubadour in the white hat moves excitedly back and forth across the proscenium. Speaking directly to his audience, he tells them how much he misses his little girl in Alaska. He strums a full-bodied G chord and sings, “Dear Darcie, here’s a letter from a guitar. He told me I should sing his song for you.”

I shoot an angry glance at my own guitar in the corner. What the hell? Are you watching this? The troubadour’s voice booms and shakes the walls of my trailer. He finishes, and the crowd goes ape. Everyone in the theater is on their feet. He takes center stage, holding his hat high, and says, “I’m Steve Fromholz. Thank you and God bless.”

I hadn’t heard that name before, but Fromholz had already been at it for a while. In 1969, as part of the duo Frummox, he put out Here to There, which may just be the first specimen of cosmic-cowboy country music ever; it predated Willie Nelson’s official departure from Nashville by three years. He never achieved the renown of some of his contemporaries, or of some of us who followed his example, but there’s a reason the Legislature named him Texas’s poet laureate in 2007. Over the years, I saw Fromholz play everywhere from mega music festivals to pin-drop-quiet coffeehouses. I loved his joyous, frenetic performing style, but it’s his songs that have always rung my bell. They’re poignant, bucolic, and funny. Never boring.

Here’s what I learned about songwriting from Fromholz:

1. Write what you know—e.g., his classic “Texas Trilogy.”

2. No subject is too strange (“Some folks say that bears go around eating babies raw”).

3. Engage in ruthless self-examination. In his greatest and most famous song, “I’d Have to Be Crazy,” he admitted, “I’ve done weird things,” and came clean about an unexplained hallucination in which he was “following ants as they crawl ’cross the ground,” then reassured us that he was all right, “ ’cause I’d have to be crazy to fall out of love with you.” But the first two lines are the ones I remember best: “I’d have to be crazy to stop all my singing and never play music again. You’d call me a fool if I grabbed up a top hat and ran out to flag down the wind.”

On January 19, 2014, Steve Fromholz put on his top hat and ran out to flag down the wind. The singer left the stage, and the picture on my ten-inch TV turned back to snow. All was quiet. I closed my eyes. “Thank you and God bless,” I whispered.

- More About:

- Music

- Robert Earl Keen