Today is Monday, late afternoon, and I have waved fourteen times so far. I’d say that is an average day of waving in Marfa. On certain holiday occasions—the Marfa Lights Festival, Christmas—there might be considerably more waving due to an influx of folks coming home for family reunions. Certain other days, like Super Bowl Sunday, require almost no waving, since everyone is inside. Most of today’s waves were administered from my truck to people ambling, biking, or skateboarding down the street or those traveling by vehicle in the opposite direction. Two waves were directed at people exiting the post office. Two were aimed at acquaintances a few aisles away in the grocery. One was for a former neighbor watering his zinnias. It should be noted that I received waves in return from everyone except the lone pronghorn buck near my gate to which I waved as I left the driveway. He did not reciprocate the gesture, but he seemed grateful enough for the acknowledgment.

Only recently, while visiting my parents in San Antonio, did I recognize how much we wave at home. In San Antonio, where we lunched with relatives, trolled the outdoors store, and prowled Costco, we hardly waved all day, except as a thank-you to a considerate driver who let us change lanes on I-35. I suppose the lack of big-city wavers is a matter of anonymity, given that most people are unknown to one another.

But in a place as small and isolated as Marfa, waving is important. It’s a way to say “I see you over there.” A wave means “You and I occupy the same space. You are there and I am here and we are in this place together.” A wave is a validation of being alive, an acknowledgment that the other person exists. It requires only an instant of effort, a gossamer contact that floats across the street or aisle, a single motion that can link one acquaintance to another. Waves are equalizers, for you tend to wave at people you don’t like as well as people you adore. There’s a tiny speck of love in a wave. “You, over there! I see you! You matter!” Isn’t that lovely? So much grace and generosity packed into one simple act.

Such gestures are meaningful in Marfa. Now there are tourists and visitors aplenty here, but waving is a habit left over from a not-far-distant time when the only folks around were fellow Marfans. If trouble befalls you and one day your proverbial ox is in the ditch, the people who show up to help are those nearby. You’d best be on good terms with them. Or if not good terms, at least waving terms.

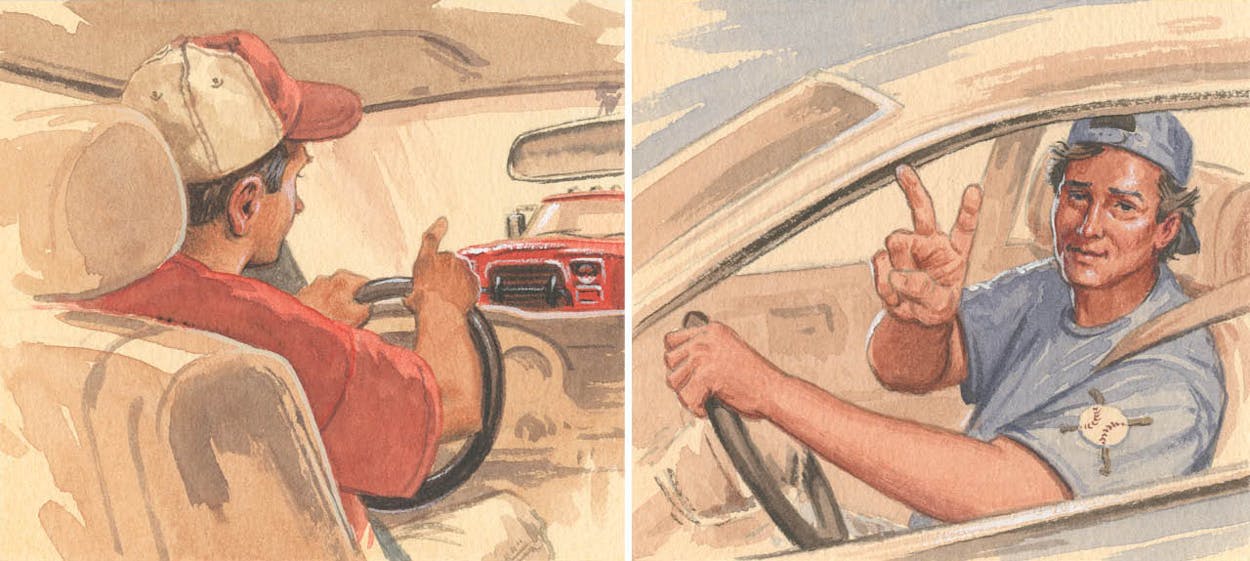

Waves fall into general categories. There is the Hi Sign—a mere lift of one or two fingers off the steering wheel—shared between drivers going in opposite directions. Drivers deploying this wave are not necessarily acquainted with one another. (“Geez Louise,” a New York friend said as I drove from Van Horn to Marfa, Hi-Signing the whole way. “You know all these people?”) There’s the Wassup, a sort of two-fingered stab in the air between guy friends. For casual acquaintances, there’s the modest Hello wave, where the row of fingers bats down two or three times in quick succession. The Howdy has a happy side-to-side action and is reserved for favorite people, like close friends or grandmothers. The Howdy can morph into the Hey Howdy, which involves an arm motion from the elbow up and a loopy grin. This type of wave is so enthusiastic that receiving one is a day-brightener. Someone giving you a Hey Howdy really likes you.

Occasionally there is the Mistake, which is any of the above waves that fizzles when the waver realizes that the person to whom he was waving is not the person he thought he was waving to. There’s the Bye-bye wave from across a crowded party, signaling friends that you’re leaving. There is also the cousin of the wave, the shoulder or elbow touch, usually deployed when the toucher is standing and the recipient of the touch is elderly and seated. If your hands are full, a brief thrust of the chin toward the other person is an acceptable substitution for a wave, but the chin thrust is not as good as a wave. Finally, there exists the Law Enforcement wave. Not everyone does this. Some folks, however, my husband among them, are compelled by forces beyond reason to wave at every sheriff’s deputy or trooper parked in bar ditches across Texas. The deputies and troopers, for the record, do not wave back.

For the rest of the population, there are definite ramifications for not waving. Years ago, a member of my softball team approached me at practice with knitted brows and balled-up hands. She’d driven past while I walked my dog, she said. She’d waved but I had not. Was everything okay? Had she done or said something to upset me? Whoa! Of course we were cool, I replied, I just hadn’t seen her. Balance again restored, we trotted to the outfield.

These stories are not uncommon. When my friend Agustín doesn’t receive a reciprocal wave, he makes an effort to talk to that person the next time he runs into them. If their interaction is normal and chatty, he won’t bring up the missed wave. If the talk is strained, an investigatory conversation is in order.

A well-played wave can mend a rift in a friendship. There used to be a bar here called Lucy’s Tavern, whose owner was taciturn and independent. Lucy wore her salt-and-pepper hair in a mannish pompadour, and she favored neutral-colored polyester pantsuits and sensible shoes. She held exceptionally strong opinions about innumerable topics and would not truck with dissension or alternative points of view. Some folks found this trait surly and off-putting; I thought she was terrific. Signs within the establishment fairly shouted at bar-goers: “No Dogs!” “No Spitting!” “No Cursing!” Although the beer was cold and the place had pool tables, the bar was almost always empty, for its patrons commonly disappointed Lucy and she would permanently eighty-six them for what she regarded as glaring indiscretions.

My friend Teresa was once thrown out for spouting off a wisecrack to something Lucy said. Months passed. There weren’t many places to go in Marfa, and Teresa wanted to earn back her entry. One afternoon she spied Lucy’s car approaching as she walked down the highway. Teresa let fly a great big Hey Howdy, and before she could stop herself, Lucy waved back. Mid-wave, she paused and scowled. It was too late. She’d responded, and thus all must be forgiven. Two days later, Teresa bounced into the bar, full of sunshine and light. Lucy handed her a Lone Star and told her, “You got a smart mouth.” They never spoke of the banishment again.

A road called RM 2810 winds southwest from Marfa to the Rio Grande, where it dead-ends near the river. The first 32 miles of the road are paved. The remaining 20 or so miles are mostly a slow-poke, gravel adventure through Pinto Canyon, a dramatic one-lane plunge that involves steep drop-offs, hairpin curves, and a staggering, wild beauty. Halfway through the canyon there is a spot where three or four cottonwoods stand in a clutch along Alamito Creek. These are strong, old trees that grow close together. Long ago, I was told, a family traveling through Pinto Canyon broke down with no provisions at this place. The father of the family left and hiked out of the canyon to summon help. His wife, Eleanor, remained camped at the creek with their children. Whether they waved as he left, I do not know. According to the story, the father mysteriously did not return, and Eleanor and the children perished. Over time, the cottonwoods grew where they died. It is a beautiful and quiet place. In our household we call that spot the Trees of Eleanor.

My husband, Michael, was bumping along this road on a gray afternoon 21 years ago, driving back to Marfa after helping to bury his friend and former employer Donald Judd at Judd’s ranch near the Rio Grande. Michael was two or three years out of Texas A&M back then. We weren’t yet married. We weren’t yet grown-ups. Judd’s death was the first important personal loss Michael had experienced, and as he drove he sifted through the profundity of the moment. He’d stopped working for Judd before Judd knew he was sick and had never gotten to say goodbye. Now Judd was gone.

A few miles down the road Michael came around a bend and encountered half a dozen men by the side of the road whom he recognized from town. This group of friends worked together as electrical linemen. They were a little older than Michael; they had mortgages and kids and positions in the volunteer fire department. These guys had started their day in Marfa that morning and driven to the river to fish. They were taking all afternoon to get back, driving a little while, then stopping along the road to drink a beer and grill venison on a hibachi they kept stoked. One of the group stepped into the road and hailed Michael to pull over. Michael didn’t want to stop and was in no mood for company, but when the lineman saw his eyes, his wave became more insistent. Michael complied and emerged from the truck, weepy. The men asked what was wrong and shook their heads in condolence at the news of Judd’s death. They gave Michael some venison and handed him a beer. They consoled him, told stories they’d heard about Judd, squeezed his shoulders, and when it was time to pack up and move down the road a piece, Michael drove along with them.

They stopped at the Trees of Eleanor, put more venison on the hibachi, and joshed around. And then something changed. Amid the unbidden kindness and acceptance of these men, none of whom he knew well, Michael’s sadness shifted to sweetness. Grief will do that sometimes, show you a path among the trees. He realized that his place in the world was in Marfa, where I was waiting. Everything that had happened led him to this moment by the creek. Although we’d known each other only a matter of weeks, Michael realized, with suddenness and with clarity, that we’d build a life together. Nothing else mattered. We would go on to marry, buy an old house, rear a child, work hard. We’d make friends and bury friends. It was going to be okay.

Michael climbed into his truck, looked at his friends through the rearview mirror, and raised his hand in a farewell gesture. The men raised their hands in return, and Michael started home. The leaves of Eleanor’s cottonwoods fluttered in the treetops and continued to wave long after he was gone.