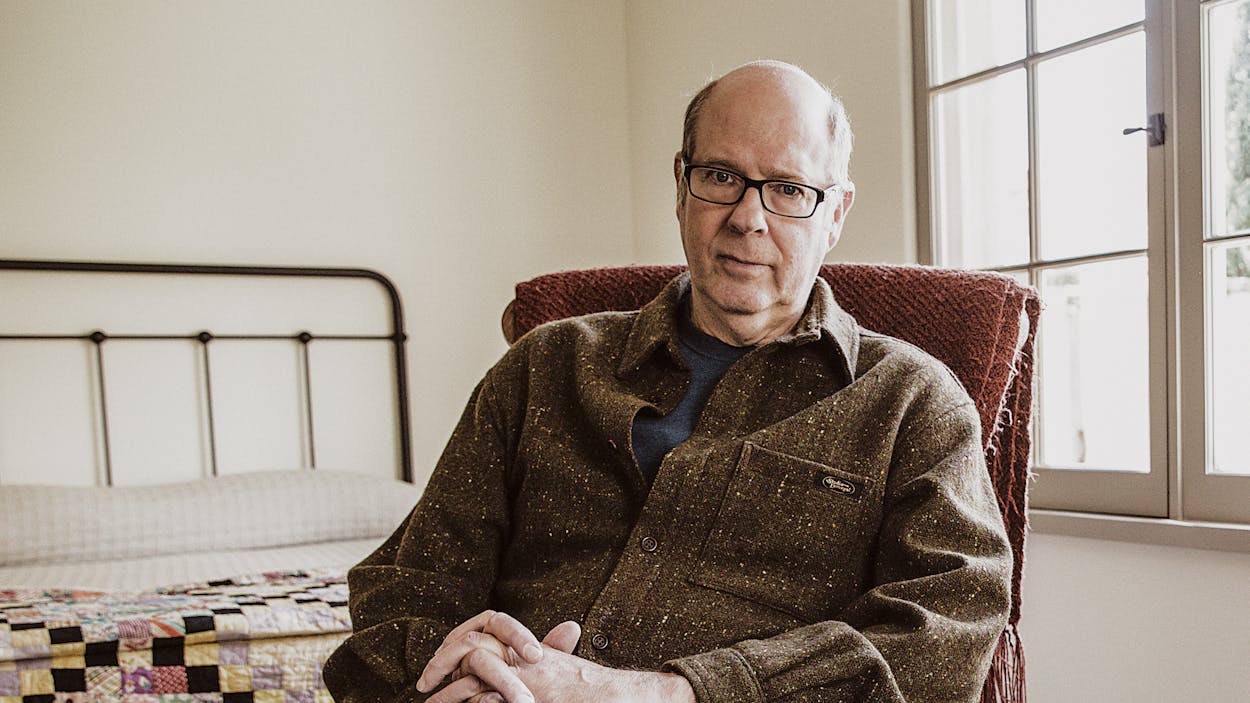

Even if the name Stephen Tobolowsky doesn’t ring a bell, his face probably does. The oft-bespectacled actor has appeared in dozens of television shows and more than two hundred films; he’s perhaps best known for his turn as the insurance salesman Ned Ryerson in the 1993 classic Groundhog Day. But in recent years the 65-year-old thespian has branched out into the world of podcasting (“The Tobolowsky Files”) and publishing; his 2012 book, The Dangerous Animals Club, is a collection of autobiographical essays inspired by his idyllic childhood in Dallas’s Oak Cliff neighborhood. His new book, My Adventures With God, will come out later this month.

Domingo Martinez: How are things?

Stephen Tobolowsky: Things are really—knock on wood—pretty good. Some neighbors found a wild rabbit out by the preschool, and they know that we like rabbits, so they called us down there and [my wife] Ann caught the rabbit and right now it’s running around outside. Yesterday I petted the rabbit for the first time.

DM: Rabbits can be skittish. Be careful.

ST: I’ll take that as a warning. But he seemed to enjoy the petting.

DM: So how did this new book come about?

ST: After The Dangerous Animals Club came out, Simon & Schuster called and said, “Could you write another book?” They had noticed this theme of spirituality in Dangerous Animals, so the specific request was “Could you write a book on faith?” Of course I said yes before I had any idea what I would write. And then after thinking about it, I realized that my life and the life of just about everybody I’ve met follows the template of the Old Testament.

DM: Interesting.

ST: For example, all of us have a Genesis story about where we came from—our families, where we originated. The first questions on a first date over a first glass of chardonnay are usually our Genesis. Who was your first teacher? How did you grow up? Then we all go into slavery, like in Exodus, except instead of building pyramids, we go into slavery with first love and first heartbreaks, with menial jobs that don’t fit our dreams. And then, like in the book of Exodus, we eventually become free, only to find that we’re still wandering in the wilderness. Then we all have this Leviticus moment in the middle of our life where we say, “Wait a minute. This is what I am.” For me, that’s when I met Ann. That’s when I had children. That’s when I said, “This is what my life is going to be.” And that’s when I found my way back to the synagogue. Then, like in the book of Numbers, we’re shaped by mortality. People we love pass away, and the visions of our own mortality begin to shape us. Finally, as in the book of Deuteronomy, we tell our stories like Moses told the children of Israel their stories, because they forgot what they were doing because they were wandering for decades in the wilderness. And we tell our stories to our children to try to make sense of our own journey.

DM: From listening to your podcast, it doesn’t seem like faith was very present early on in your life. What changed?

ST: In the middle of my life, when I came back to the synagogue, I found there was a comfort in the validation of tradition. I had one moment in the synagogue that completely turned me around. When I first started coming back, I went to a service one Saturday morning. I was the only person in the synagogue. No one had shown up but the old rabbi. And the rabbi said, “What, do you think it’s something I said?” And then he said, “Come on, come on up here with me. Are you afraid to pray with an old man?” I said, “Oh, I’m very afraid.” “You should be,” he said. “Listen, we’re going to take this opportunity to feel these prayers, to understand these prayers; the psalms are beautiful, you should understand the beauty of the psalms and enjoy them. Let’s just start this together, you and me.” And that is when I realized that the religious moment is a solitary moment, it’s not a group moment. If you look back through the Bible, every real experience someone has with God, they’re alone. You have Moses and the burning bush, you have Jesus at Gethsemane, you have Abraham looking out at the stars of the sky with “the stranger,” who might be the personage of God. And that’s when I realized, wait a minute, what we’re talking about when we talk about faith is an element of our life that changes through our life, just like my waistline. I found this comfort in tradition, and I felt like I was able to be a student again and study the Torah and the Talmud and the Mishnah.

But then later in my life I started having catastrophes—I broke my neck, I had open-heart surgery. And in those moments my faith became something other than scholastic, and I began to feel the real power of the invisible and of faith, and the possibility of a miracle. A lot of times people like to think of miracles as something akin to a magic trick, but the way I see a miracle is when your mind suddenly changes and you see something that you never saw before.

DM: How did you make the transition from acting to writing? I’ve met a lot of people who were phenomenal storytellers in person, but they couldn’t get that voice that was in their head onto a piece of paper.

ST: I think I always had the ability to write. When I was an undergraduate at SMU, I made money by writing people’s master theses and Ph.D. dissertations. What I would do was, I would ask for a writing sample from them and use my acting instinct to inhabit their writing sample. I would write in their voice so it wouldn’t sound like somebody else wrote their paper. I got used to impersonating different voices, and I guess I was able to impersonate my own voice.

DM: On your podcast you’ve mentioned the high you get after you write something or create something.

ST: There’s really nothing like it. Sometimes, my “writer” is in. I’m there all day in front of the computer and I’m in ecstasy and I’m having so much fun and it’s so divine. And the days when the writer is not in, I realize, “Oh, it’s a day to do something different.” And I’ll go back and reread what I’ve written and try to correct words, try to change words around, try to refine what I’ve written. And if the writer is really not in at all—he’s gone fishing and put up a sign on the door saying, “Don’t even bother knocking”—what I do is, I go fishing too: for inspiration. So those are the days I’ll do research. I’ll read the Talmud. Or I’ll listen to music I’ve never listened to before. Or I’ll take a walk and try to get some input that maybe will stir something up. I put everything in service of the writing monster.

DM: Any other writing tips?

ST: In his books Creating a Role and Building a Character, [Konstantin] Stanislavski says that when you’re working on a part you should do light exercise—nothing heavy, nothing strenuous—because you need to be physically distracted a little bit to force your concentration to move into a more operative place. Maybe it’s the same thing with writing. Do dusting, walk to the park, observe people, clean dishes. That kind of thing. At our house, I think about things in the morning when I shuffle the cat litter.

DM: And it works out.

ST: I had dinner the other night with a friend who has just gotten through pancreatic cancer, and she’s alive and she’s in remission and she’s well. And she told me that she heard me perform “Conference Hour,” the story I wrote about the teacher in college who was trying to destroy me and how I survived that.

DM: That’s a great story.

ST: And she said that she heard me reading that story two weeks before she had to go in for surgery, and it changed her outlook. Now, I’ve heard several people say that they felt that that story was their story. But that story is not their story, you know? That was a story of a kid in school dealing with a brutal teacher. This woman is dealing with pancreatic cancer and possible life and death. But when you tell a true story, whatever that true story is, there’s a chance that someone will see their life in the truth of your story, even though it has nothing to do with their story. If you tell a clever story, maybe people will remember a joke or a line from it, but the odds are they aren’t going to see the truth of their life in it. Which is why I love telling a true story. That’s what I’m into the most, if I can tell it well.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.