This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

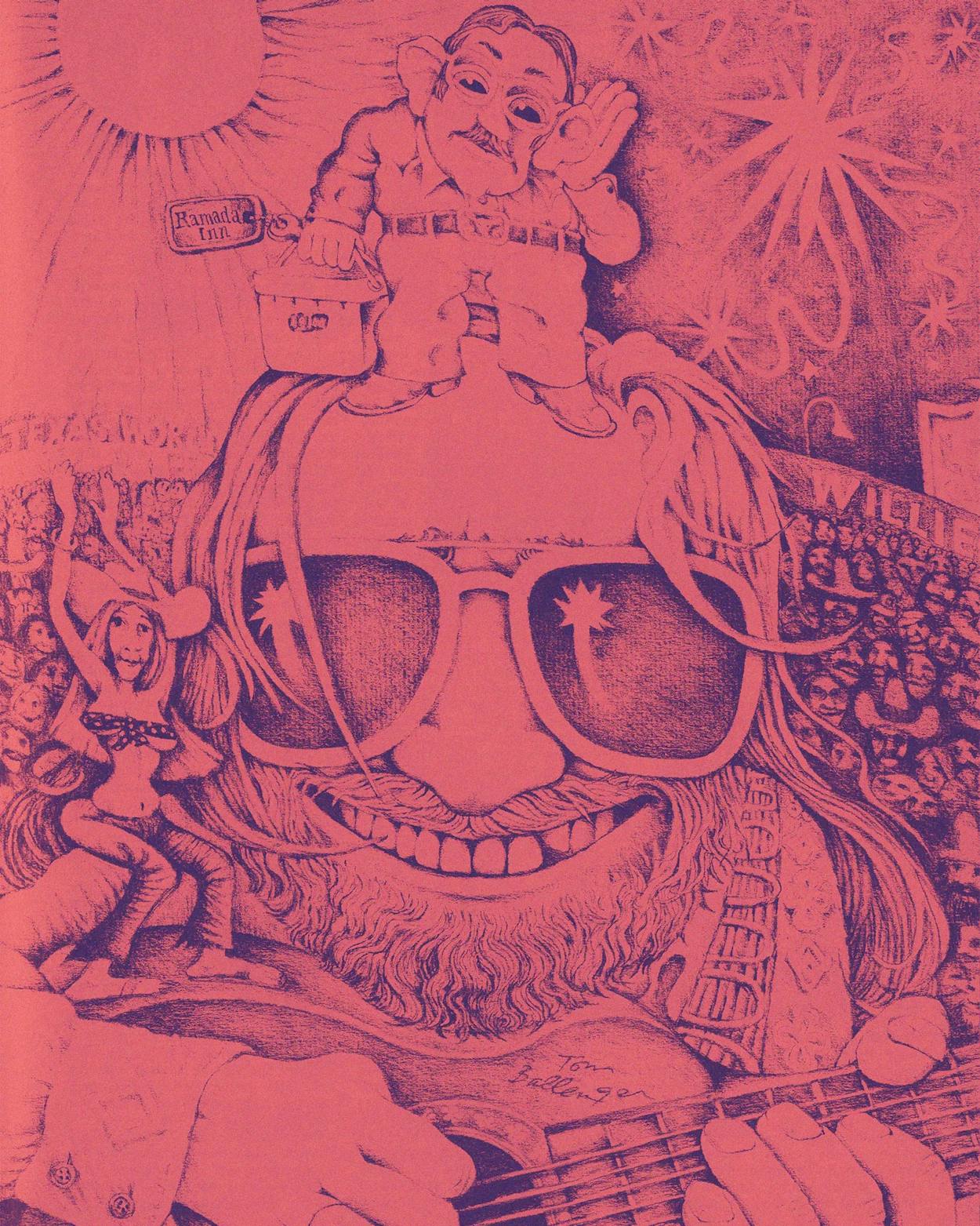

I don’t much like heat or dirt or loud noise or even being outdoors for long stretches at a time, but I do like picnics and special events and crowds and country music and Willie Nelson. So when Willie first announced he was organizing a three-day Fourth of July Picnic featuring 36 hours of traditional and progressive country music, and expected 50,000 people to be there, I made up my mind to go, and I went. I thought you might like to hear about it.

The picnic was held in the 160-acre infield of the Texas World Speedway south of College Station, an inhospitable site attractive to promoters because it is highly resistant to gate-crashers but as barren of trees or other shade as it has been of auto races. Yet as I joined the crowd walking through two long tunnels to the infield, I sensed that we had come because we knew the stark landscape and three days of searing heat would inflict great suffering, and since our lives are so easy and our chances to test ourselves against the elements so few, we grimly determined to pursue a happiness of discomfort on this our nation’s birthday.

At the top of the grade coming out of the tunnels, where we had felt the last coolness of the day, members of the volunteer medical staff handed out free salt tablets with the promise they would help us last two extra hours if we drank a lot of liquids. Most of the people walking in with me looked prepared to heed the advice on liquids, having estimated their needs at approximately one case of beer per person. I was impressed. Even at the American Legion picnics I went to when I was a boy, nobody would come close to drinking that much beer except oilfield workers and Catholics.

The crowd was not quite what I had expected. It was probably no larger than half the hoped-for 50,000, but what surprised me more was its composition. I had expected thousands of cosmic cowboys and assorted freaks, but I had also expected fairly large numbers of authentic rednecks, and I knew if I got uncomfortable with freaks I could go sit with the kickers. I am not trying to pretend I grew up a redneck, because I didn’t. We were town people. My daddy ran the feed store and was president of the school board, my mama was big in the PTA, and I knew when I was five years old that I was going to college. But I also knew a lot of rednecks and, if it came right down to it, I figured I might feel more at home with them than with long-haired hippie weirdos eating toadstools and smoking LSD.

There were some kickers there, all right. About six. The other 25,000 were freaks or freak-ish, all under 25. I began to realize that I stood out, because I was wearing an honest-to-goodness western shirt with pearl grippers and, at age 36, I was a Senior Citizen. Clearly, I was a stranger in a strange land. This was the case: the closest I had ever been to an event like this was watching the first half of the Woodstock movie. I found a spot to set my cooler down and spent most of the Fourth just paying attention.

For those interested in fashion, it can be reported that the Gatsby look has not taken over everywhere. It’s probably just as well, since white is not practical without a certain commitment to cleanliness. Still, observable regularities of dress indicated the young folk had indeed thought about what they were going to wear. The standard uniform for “dudes”—a useful designation for someone no longer a boy but not quite a man—consisted of jeans and sleeveless shirts. With rare exceptions, “chicks” wore shorts and halters. A lot of the dudes walked around with jockey shorts sticking out of the waist of their Levis. I used to have nightmares about showing up in public places in my underwear, but it didn’t seem to bother them. Sometimes they had holes in their pants and you could tell they didn’t even have on any underwear or, if they did, that it was all worn out and torn. What if they were in an accident? The police would take one look at their underwear and send them to the charity hospital.

If there was sameness in Levis and shorts and sleeveless shirts and halters, there was marvelous variety in cap and hat. There were derbies and dapper Panamas, porkpies and pith helmets, hard hats and Hombergs, mountaineer hats and Scottish tams, Budweiser hats and Lone Star visors, golf hats and tennis hats and fishing hats, fatigue caps and baseballs caps and railroad caps, Dodge Truck and Yamaha Motorcycle and New York Air Conditioning caps, International Harvester caps and Caterpillar caps just like the man wore in the cafe in Easy Rider, lumberyard caps and polka-dot paint caps, and caps advertising Lone Star Feed and Fertilizer, Equidyne Horse Pellets, and the Athens Livestock Commission. Those who had neglected to bring hats fashioned substitutes from T-shirts and jockey shorts, or by jamming a six-pack carton on their heads, or by combining a Budvisor with a Holiday Inn towel to create the look of an ersatz A-rab from the burning sands of Cairo, Illinois. Most common, of course, were beat-up western hats, with the brims flattened out or bent down in front to look mean. At kicker dance halls, skilled laborers try to look like ranchhands. Here, unemployed students were trying to look like rustlers. I understand the desire to dress up, but if I were picking a costume, I would choose a black and silver outfit and pretend I was a town tamer. My name would be Johnny Laredo.

After I got my bearings I began to pay closer attention to the music. I had been a bit apprehensive about how I would respond to three days of what has come to be called “progressive country” or, more recently, “redneck rock.” I like country music because the tunes are easy to remember and I can understand the words. I don’t like most rock music because it is too loud and straining for the words seldom proves worth the effort. I just didn’t see how country music was going to gain much from crossbreeding. I do like some rock, of course. I’ve got two Carole King albums and a Neil Diamond tape and I really enjoy the Living Strings version of “Hey Jude” and “Let It Be” on KYND (“All Music, All the Time”). I had liked a good bit of what I had heard of progressive country, especially Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Murphey and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and I had been told I would like Greezy Wheels and Freda and the Firedogs and several others, but I had never gone to hear them in person because they usually appear at places where people stand up and walk around and make a lot of noise. So, really, I was open, and I’m glad I was. I picked up some new enthusiasms.

One of the groups I enjoyed most was Jimmy Buffett and his Coral Reefer Band. Buffett started out with a song about wishing he had “a pencil-thin moustache, a two-toned Ricky Ricardo jacket, and an autographed picture of Andy Devine.” It made me think about the time I got Lash LaRue’s autograph—for all you older people who have wondered whatever happened to Lash, he did a night-club act in Juarez for a while and is now a street preacher in Florida, bullwhipping for the Master. Buffett claimed the fellow who wrote “Pencil-thin Moustache” is named Marvin Gardens; I imagine he lives in a yellow house near the water works and pays $24 rent. When Jimmy rendered a lament for the fact that “They don’t dance like Carmen Miranda anymore,” I was about to decide I could come to like his work. Then he sang a number called “Why Don’t We All Get Drunk and Screw?” which I found not only a sharp break with nostalgic themes, but a rather more direct sentiment than I like in my love songs. I really prefer something a bit more sensitive and delicate, like Snooky Lanson and Dorothy Collins singing “Lavender Blue—Dilly Dilly.”

The sound system was excellent, performers were reasonably good about sticking to half-hour sets, and in the relatively short exchange time between groups we got to hear Kris Kristofferson records, which was fine with me since I think Kristofferson is the greatest living American next to Carl Yastrzemski. At the beginning of an act, or at any point when enthusiasm seemed to be waning, most of the performers could be counted on to say something like “Hot Damn! Aren’t we having a good time at the Willie Nelson Picnic?” or “Who in the entire globe of the planet earth could ever put something on like this but Willie Nelson?” which inevitably drew automatic shouts and applause of the sort right-wing politicians trigger by calls for law and order or tent preachers get when they ask their flocks to say Amen if they love Jesus. Despite these periodic outbursts, however, the crowd paid no more than half-hearted attention during most of the acts. They knew the music was playing and moved their feet or hands or something, but treated it rather as if it were background music, except that it was hard to determine what it was background to. They really did very little except drink and smoke and stare.

There were exceptions, of course. When Augie Meyers and his Western Headband played, a dude with a benign but decidedly crazy look danced around off the beat, blowing a harmonica and kicking dirt on the folk around him. Even though he had lost a lot of his fine motor control and could never have handled the Samba, especially on the trickier steps like the Copa Cabana, he did have spirit, a quality that marked him from his peers. Directly in front of me three of the most taciturn young men I have seen in some time, including one who was a dead ringer for my Cousin Bolo (that ’s not his real name, of course; his real name is Little Walter), sat for ten hours passing beer and dope but no more than 50 words. Once, the one in the middle leaned over and threw up between his feet. A girl stepped over and rubbed his back with his wadded-up shirt and in a few minutes he straightened up and resumed his torporous attitude. As far as I could tell, his friends did not notice. Behind me, four boys about the age of my sons—thirteen and fourteen—managed to sustain a state of unbroken somnambulance by alternating between beer and marijuana. A couple of times, the youngest, who might have been no more than twelve, offered me a joint, for which I thanked him but no-thanked him. I’m pretty sure there is a law against taking dope from a twelve-year-old.

Picking one’s way through a crowd of 25,000 people, sitting or lying next to one another like stricken pilgrims at the Ganges, is a delicate maneuver at best. For those whose sense of height and depth had been altered by marijuana, it became an assignment of mammoth proportion. I watched one boy make three unsuccessful attempts to lift his foot high enough to get over the edge of an army blanket lying flat on the ground. He finally gave up and took another route. But perhaps what was lost in precision of movement was regained in a greater capacity for informal adaptive measures. A chick clad in shorts and two bandanas tied loosely above her breasts, managed the task more effectively by offering people a hit off her Schlitz in return for safe passage. She will be a good wife for some nice young man. She’s frugal, friendly, resourceful, and makes her own clothes.

On another occasion, a dude with a pleasant grassy look stumbled into the neighborhood and announced he felt a certain sexual tension, or words to that effect: “Anybody wants me, come on. I don’t mean to be nasty, but come on. Right here.” In a similar spirit of forthrightness, a wild-looking youth lurched into the vicinity and began to ask loudly, “Would anybody mind if I take a piss right here? Be honest.” I admired his direct approach; I recognize that urination is just another bodily function and nothing to be ashamed of, and because I was a member of a minority group, I was somewhat reluctant to insist that his needs violated my sense of territoriality. Still, I was as relieved as he was not, when my younger neighbors suggested he move on. No more than twenty feet behind us, however, he found an accommodating group willing to step aside for him, and he took his ease for all to see. As a reciprocal gesture—and we know that reciprocity is essential to community—he offered us a good price on that which had so relaxed his inhibitions: “Anybody want any Quāāludes? Anybody want any reds?” His sense of enterprise encouraged me about his generation. As my father used to point out, being able to sell is the best job security a man can have. It’s as good as a teaching certificate for a woman.

By late afternoon, the combination of sun, alcohol, and drugs had taken a terrible toll. The heat, though relieved slightly by a brief shower, was simply awful. I was uncomfortable, but managed to avoid collapse by continual intake of liquid. I don’t know what the record is but I was quite surprised to learn that it is possible to eliminate through the pores of one’s skin the liquid from twelve cans of assorted beverages and a 70-cent sack of ice. No lie. Members of the medical staff circulated through the crowd, pushing salt pills and spraying Solarcaine on the lobstered backs of people who had gone to sleep or passed out. The medical center itself resembled a ward for the insane as kids jammed in for treatment. Many were badly burned and crying, others were upset and uncomfortable from the unhappy effects of mixing Quāāludes or other downers with alcohol, a few who had taken LSD worked with modeling clay and colored pens, and half a dozen kids had to be sent on to the hospital after what a sadist had sold them as THC or given them as salt tablets turned out to be either rat poison or strychnine. A staff member who worked in the medical center all weekend said later, “It was really very sad. So many were having such a horrible time. They’re hot and dirty and really, really sick, and wishing so much they had not come.”

Of those who never made it to the medical center, hundreds slumped around in a red-eyed stupor, as if the life had gone out of them. They may have been watching Fantasia in a theater-of-the-mind that was twenty degrees cooler inside; on the outside they looked hot, tired, and miserable. But they had told their friends they were coming and they would want to tell them they had had a good time, so it was necessary for them it stick it out.

Even after blessed night finally came and the temperature dropped into the bearable range, it was hard to strike and hold a truly festive mood. A little after ten p.m., Jerry Jeff Walker began a highly promising set, but was interrupted repeatedly by unscheduled fireworks and emergency medical announcements. Most of the fireworks were roman candles and cluster rockets, but a few less socially conscious persons threw large firecrackers into clumps of people and one of the rockets zipped into the crowd and burned a spectator rather badly. The management declared there would be no more music until the fireworks stopped and the pyromaniacs eased off momentarily, but when the music started up again, so did the fireworks. Unnerving as they were, they added a nice touch when Jerry Jeff sang “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother.” At precisely the moment that 25,000 people yelled “REDNECK!” the biggest and most spectacular rocket of the night burst into a sparkling cluster high over the stage. It was the sort of thing that happens in movies.

What followed was the sort of thing that happens in bad dreams. The medical staff had gotten a report that a woman somewhere in the crowd was in a coma from insulin shock and needed immediate attention if she were not to die. Trouble was, they didn’t know just exactly where she was, so would we check out the unconscious chicks around us and see if any of them appeared to be in insulin shock and if we found one, would we please yell out while everybody else got quiet? Most of the crowd got quiet but a good many yelled out from different parts of the audience—for a joke, probably, but given the number of unconscious people strewn about, perhaps not—and one guy called out, “Anybody got any downers?” I wondered how many of those who laughed were diabetics, and I wondered at the capacity of my fellows to laugh when one of their number might be dying. But, as someone called out, we had come to hear music, not to look for sick chicks, and after a bit the show resumed. As it turned out, the delay and search had been unnecessary. The diabetic in question was not a girl but a boy named Val, and he had already been treated before the announcement was made, but the irritation of the crowd at having their concert interrupted by what appeared to be a hoax did not augur well for the survival chances of other medical emergencies.

In fact, the medical people did report some difficulty with the crowd, especially on the first two days. Rory Harper, one of the supervisors of the medical staff, said, “Occasionally people even pushed the stretcher crews back and wouldn’t let them through. Or we would be trying to treat someone who had passed out and somebody would yell, ‘Give her a couple of Quāāludes and she’ll be all right.’ They were either stoned or just didn’t give a damn.”

To climax the confusion, operations manager Tim O’Conner took the microphone to announce that a peculiar Texas law governing mass gatherings required that the show end promptly at eleven o’clock. Not only would the last four scheduled acts be canceled, but Jerry Jeff would not be allowed to come back for an encore. As the young folk began yelling about rip-offs and suggesting that the law and its agents occupy themselves in acts of sexual self-gratification, I feared there might be some unpleasantness. But this was not a violent crowd and the height of the objection came when a young man stood on a beer chest and screamed frustratedly at O’Conner: “You’re a fart!” It is possible to be irritated with a person so designated but one does not lynch him. Defeated, perhaps at some level relieved to have the ordeal ended without having to admit they were ready to quit, the crowd filed out peaceably.

It may be that anything worth doing is worth doing to excess, but as I eased my ravaged body into the soft bucket sets of my little red station wagon, I reckoned that the folks who schedule three-hour concerts in air-conditioned auditoriums have a basically sound idea. And as I drove past the tired, dirty kids bedding down in the Willie Nelson Approved Campsites next to the Speedway, I was pleased that because I have this good job teaching school and writing stories, I could afford to stay at the Ramada Inn. I caught the last part of No Time for Sergeants on the motel TV. I could have seen all of China Gate if I had wanted to.

On Friday, July 5th, I awoke at noon and enjoyed a delightful breakfast of pizza and iced tea, which I preferred to the Alice B. Toklas brownies and Kool-Aid I imagined the kids were eating out at the Speedway. I didn’t go back to the picnic until about four o’clock, but that was early enough. I still managed to get in a full day’s entertainment.

Despite what was probably greater heat—reports of 103 may have been exaggerated but indicated what folk thought of the weather—most people seemed to be suffering less than on the Fourth. Hundreds of umbrellas and makeshift sunshelters had been erected, creating the appearance of vacationers who had headed for the beach but missed. Apparently because most people took salt tablets and upped their liquid intake, the medical staff had far fewer cases of heat prostration. But in its place, they treated thousands of cuts that resulted when the threshing action of a grounds-cleaning machine left millions of small chunks and shards of glass lying in wait for romantically bare feet.

I roamed a good bit on the Fifth and found the much smaller crowd friendly and relaxed, even though the young folk kept confirming my sense of strangerhood by asking, “Are you having a good time, Sir?” and “What’s happening, Daddy?” I wanted to point out to them that most of the performers they liked best were a lot closer to my age than theirs, and that having never heard of the Lost Gonzo Band or the Neon Angels did not mean I had ridden into town on a head of cabbage. I wanted to tell them about the time I had breakfast at Cisco’s Bakery in Austin with Willie Nelson and Tom T. Hall and Coach Darrell Royal, or about hearing Bill Monroe when Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs were part of his Blue Grass Boys. I even considered telling them about the time I heard Gene Krupa and Charlie Parker on the same night, but I didn’t want to have to explain who they were. Mostly, I just smiled and said, “Fine.” But when the third person of the day asked me if I was a sheriff, I asked him whatever had made him think I might be. He said, “Well, it’s your shirt.” I asked him what was wrong with my shirt. It’s a good shirt. My wife gave it to me for Christmas. “That’s just it,” he said. “It’s too good. You need an old shirt.” I don’t go along with that. It seems to me that pretending I’m poor isn’t taking poverty seriously. Besides, I don’t have any old shirts. I give them to the Goodwill and take it off my income tax.

While wandering around, I ran into several fine folk of maturity comparable to my own, but none delighted me more than Mr. and Mrs. Weldon Wilson from Wharton. Mr. Wilson, who had on grey trousers and a peach-colored shirt with the short sleeves rolled up a couple of turns and who wears his thin grey hair in a close trim, fixes TVs for Sears over at Bay City. He and Mrs. Wilson, who wore a navy blue shorts outfit with white socks and sneakers and had a chain fastened to her grey half-rim glasses so she wouldn’t have to put them down when she took them off, were enjoying themselves. “The main reason I am here,” he said, “is because I like country music. And I haven’t seen any of the kids that I don’t like. They are going to be running this world in the future and from what I have seen here I think I’ll enjoy living with them. I really do. A little girl asked me a while ago why I was here. I asked her why she asked me that question and she said, ‘Well, usually only kids come to these things. Do you enjoy it?’ I said, ‘Definitely!’ She said, ‘You don’t think we’re wrong?’ I said, ‘Definitely not! When I was your age I did things the older people thought I was wrong in doing.’ And, you know, she just loved my neck. Anyone that would say that all these kids are out here for is to get doped up, there’s something wrong with them. There might be some of it I don’t agree with, but they’ve got their own lives to live and they are going to live them, one way or another. They’ll have to pay for their mistakes, the same as you and I did, but I haven’t seen them doing that much wrong yet.”

Mrs. Wilson said, “Neither one of us has ever smoked marijuana or taken dope and we probably never will, but there is something that is funny to me. Out of all them I know that are smoking it, there is not but one I know that wasn’t a cigarette smoker first. So smoking can lead to marijuana just like marijuana can lead to heroin. And, you know, if this had been the thing to have done when I was this age, I don’t know that I wouldn’t have tried it.” Mr. Wilson wasn’t sure about that. “I’ve got enough adrenalin in my body that I don’t need anything to slow it down or speed it up. Anything they can use their smoking or their dope to do, I can do the same things naturally. Say, would you like a beer? We’ve got Coors.”

Late Friday afternoon, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band galvanized the audience into the form it would hold until well after midnight as hundreds, maybe thousands, of young people wedged themselves into a sweating, writhing, ecstatic mass of back-to-front bodies that stretched outward from the side stage in a 50-yard-wide semicircle. As the Dirt Band raised the speed and volume of its excellent music, the crowd raised the intensity of its response. Five attractive chicks persuaded their dudes to lift them onto their shoulders that they might better see and perchance be seen. I thought about how much it would make my neck hurt to have a girl sit up on my shoulders like that and how I would resent not being able to put my hands in my pockets because I would have to hold her by the thighs to keep her from falling off, but the dudes seemed to bear up under their burdens rather well.

Eventually, inevitably, one of the girls untied her halter and threw it onto the stage. Within seconds, three of the remaining four had done likewise, to the delight of the gathered multitude. As they jiggled and swayed bare-breasted through several long numbers, the plight of the fifth girl became apparent and poignant. Less abundantly blessed than her sisters, she had not foreseen, as I am relatively certain they had, that matters might come to this. As the others grew more wanton by the bar, she tightened her lips and stiffened noticeably. She could not climb down without losing face; she could not disrobe without revealing less than she cared to. I remembered young teenaged boys, friends of mine mostly, who dreaded gym classes because of the showers that followed, and I hoped she would think of a graceful exit. She did not; but as she suffered, others prospered. A striking blonde girl, whom I suspect I would recognize if I were to see her at any point during the next twenty years, slowly but surely stole the show from the others. When Willie Nelson came out to finish up with the Dirt Band, he tossed her a fine straw hat which she set at what had to be the most provocative angle possible—people who wear clothes well have a knack for that sort of thing—then threw back her head, shouted, “I love it!” and went into a magnificent shiver of the sort one seldom experiences alone. Her actions seemed to set up needs in others for similar release of tension. Several girls stripped buck-naked and tried to climb onto the stage. Most were beaten back by heartless security guards but one streaked briefly to the rear of the platform. God knows what happened to her back there with all those musicians.

As I watched this scene which did not remind me much of the dances at the Faculty Club, I thought of a sober colleague who recently confided that his secret fantasy was to be a rock star and to enjoy the adulation of hundreds of nubile young women. I remembered what Mark Twain had said about naked people having little influence in society. And I wondered what the odds were, given the fact that man has been on the earth for thousands, perhaps millions of years, that one would miss the sexual revolution by less than ten. I’m sure Weldon Wilson is right. They’ll have to pay for their mistakes the same as he and I did. But I don’t think he and I were ever offered such an impressive line of credit.

Actually, I face my missing the sexual revolution without much difficulty. I acknowledge there is a certain attractiveness to a firm, smooth, tan, lissome young body with well-fitted parts, but I have come to appreciate, perhaps even prefer, the sensual beauty of women in their mid- to late thirties, women whose eyes and smiles reflect experience not just with sex but with love, and whose softer bosoms and the gentle ring of stretch-marked waists that will not quite be contained inside their swimsuits or jeans give tangible evidence of time shared by man and child. I pondered the casualness of sexual display and of sex itself in this age group and thought that, for all its momentary allure, sex not undergirded by love, sex between people who seek their own pleasure rather than a true experience of mutuality, sex with a person one may hardly know, however attractive that person may be physically, could never be as meaningful and fulfilling as sex with a person to whom one has made a lifetime commitment and with whom one has shared the bad times as well as the good. Probably.

And I thought that if I had a hat like Willie Nelson’s I would have put a tether on it before tossing it out to that blonde girl.

All the naked bodies and reveling and such during the peak of the Nitty Gritty set had led me to believe that we might, following parallels in nature, expect things to tail off for a spell, that folk would find seats and smile about what a nice time they were having, and respond a bit more passively to the efforts of the next group or two. Probably because I failed to take into account that most of them don’t have jobs that demand much physical or mental effort—peeling avocados in health-food restaurants, sitting on the sidewalk selling jewelry, things like that—I had seriously underestimated the amount of reserve energy after two days of grooving in the sun. Here I was, trapped and unable to move, slumping under the years of gravity’s relentless pull, feet aching despite special arch supports and Comfisoles, and realizing that they intended to stay there right up to the end, which obviously was not coming soon. A friendly, smiling dumpy-pretty sort of girl explained it was precisely this kind of experience that had attracted many to the picnic. “It’s a stimulus, just like the dope and the music. It keeps you going. It’s a weird high.”

As I gathered such bits of intelligence, I recorded them for later retrieval by speaking into a small microphone tucked deep within my fist to shut out the noise of the speakers. The microphone was attached by a cord to a superb little tape recorder fastened to my belt and covered with a black leather case. When a gat-toothed young man inquired as to what I was doing when I put my mouth up to my obviously-wired fist, I told him it was electric dope, expecting no more than a smile or agreeable chuckle. Instead, his face exploded in delight and he asked if he could try it. I handed him the microphone, he took a couple of hits, shouted “Far f . . . . . g out!” (an expression more freighted with enthusiasm than substantive content), declared to his friends that it was first-rate stuff, and demanded to know where he could get some for himself.

The Friday evening program was marred somewhat by the fact that it was being filmed by the Midnight Special television show. As members of the film crew walked in and out among performers and as the cameras swept around without concern for the fact that soft human bodies were in the vicinity, one got the impression the crowd was being regarded less as primary consumer than as studio audience. Even more offensive was the presence and behavior of Leon Russell, who would serve as Wolfman Jack’s co-host for the Special when it aired in early August. Russell is a darling of the progressive country set, for reasons I cannot fathom. For three days he wandered around in what appeared to be a chemical daze, his pasty white pot-belly poking through an unbuttoned shirt and his wasted face peering out from under a straw hat perched on top of the grey hair that flowed down the sides of his face for at least two feet. Because he had obviously ordained himself to be the Big Star of the picnic, Leon felt free to walk onstage whenever an act was reaching its peak and share in the applause, just as if he had earned it. On one of his early appearances, he sprinkled beer on the crowd with his fingertips, in the manner of a Great High Priest. On another, when a groupie-aspirant handed him a box of strawberries, he took small bites from each and threw them into the crowd, to be shared in sacramental fashion. Most of the time, though, he just stood and gazed through eyes that betrayed a mind suffering from severe brown-out.

But not even Russell could ruin the evening. The Main Coonass, Doug Kershaw, gave a typically superlative performance. With his rubber face changing in an instant from Bayou Prince to Lunatic Frog, and his body contorting like a package of pipe cleaners on an acid trip, he bounded all over the stage, playing his gaudy fiddle at maniacal speed and working himself, his band, and the audience into a frenzied lather. Michael Murphey, splendid in his white cosmic cowboy suit, did a fine job with some exceptional songs and Waylon Jennings got a good reception with his hard-driving music about men that represent poor marital risks. I think things closed down about one a.m. but I don’t honestly know, because I finished before they did. As I was walking out, I heard Leon Russell take credit for getting the mass-gathering law suspended and then declare that “I never expected the Good Lord to bless me so much by having so many beautiful faces look at me at one time on the Fourth of July.” It was actually the sixth of July, but I doubt Russell knew it. In any case, his pronouncement strained my doctrine of special providence considerably, and I wished I knew where to find the young man who had hollered at Tim O’Conner late the night before. I think he might have had an appropriate word for Leon.

More from a sense of duty than desire, I went back again on Saturday. The main attraction of the afternoon was a middle-aged man who both looked and claimed to be a deputy sheriff but who walked around giving freaks the soul-brother handshake and spending what time he could bridging the generation gap with a topless chick of generous endowment. Among the invited performers, Greezy Wheels, Doug Sahm, Spanky and Our Gang, and some others did a nice job, but Rick Nelson and David Carradine helped convince the faithful it was time to go home.

I suspect most of the people who stayed all three days managed to have a good time and would probably show up if Willie announced a similar event for next week. And I’m glad I went. I enjoyed myself as well as a lot of the people, and I came to like redneck rock better than before. But late Saturday night, as I sat all showered and shampooed in my cool two-story house with the lawn and the shrubs and the bird-feeder and the basketball goal and the hopscotch grid, drinking iced tea and talking to my friends, admiring my teenaged boys and eight-year-old daughter, and thinking about my prize wife whose eyes and smile reflect experience not just with love but with sex, I decided this year’s picnic would probably last me a good while.

William C. Martin is a professor of sociology at Rice University.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Festivals

- Willie Nelson

- College Station