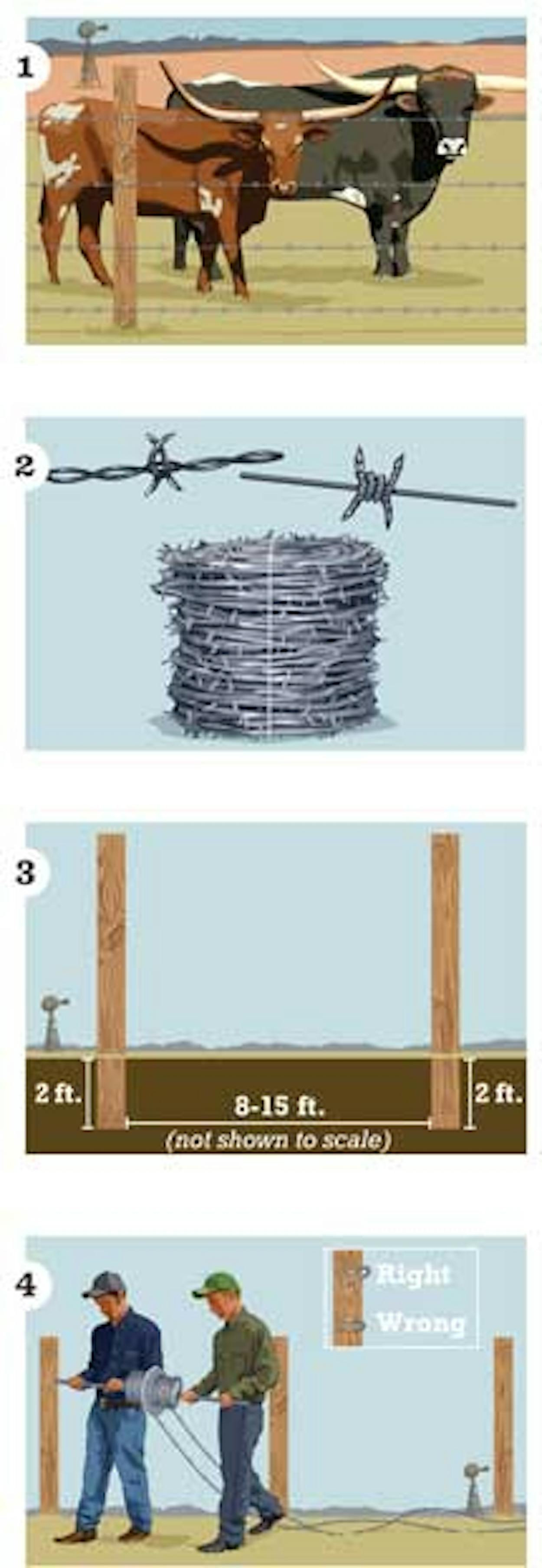

The HISTORY

In 1876 salesman John W. Gates brought barbed wire to Texas when he wagered $1 million that he could build a fence that would capably contain cattle. Some incredulous gambler took the bet. Gates erected a fence in San Antonio’s Military Plaza and shocked a gathered crowd as a herd of enclosed Longhorns backed away from eight thin strands of spiky wire. “That was a turning point,” says Davie Gipson, the curator of the Devil’s Rope Barbed Wire Museum, in McLean. “When barbed wire came along, it stopped open-range traveling the way Indians and cattlemen knew it.” It also caused some thorny relations: While farmers enjoyed better crop protection, ranchers despised the constricted spaces, and soon range wars (and wire-cutter manufacturers) boomed. Today, however, barbed wire remains the simplest and most popular way to mark your rightful territory and manage your mooing moneymakers.

The WIRE

There are more than 570 patented wire styles, many equipped with fancy barbs, but down-to-earth ranchers use the two- or four-point varieties. Because metal weakens when exposed to fertilizers or elements like humidity and sand, manufacturers offer a range of protective coatings; which one you choose will depend on your needs and your wallet. According to Brian Cowdrey, a veteran fenceman who works for the League City–based American Fence and Supply Company, class I galvanization, the least expensive, has the thinnest finish and the shortest life span—usually eight to ten years—while class III has a heavier coating that prevents rust for at least twenty years. A spool generally holds 1,320 feet, and most ranchers opt for twelve-and-a-half-gauge, double-stranded wire.

The POSTS

A fence is only as good as its posts. Invest in metal or a durable, treated wood. Or, for an authentic look, repurpose downed native trees, like cedar. The typical post measures four to eight inches wide and eight feet long. Since lengths of taut barbed wire exert heavy pressure, take care to anchor your posts well: Holes should be dug at least two feet deep (for extra stability, secure them with poured concrete) and placed roughly eight to fifteen feet apart. “The key to any fence is your corner, or end, posts,” Cowdrey says. “You need to brace them so the wire doesn’t pull your fence down.” Brace each end post using a piece of wood nailed horizontally between it and its adjacent posts, then run a length of wire diagonally between the posts to strengthen the corner.

The ASSEMBLY

After reviewing an aerial map of your property and drawing a blueprint of your intended boundaries, install the posts, then lay out the wire along the inside of the perimeter. Fasten your first strand near the top of a corner post. Walk to the next corner and, using a wire stretcher (available at most hardware stores), tighten the line, then staple it to the post there. Next, fasten the wire to each intermediate post. “Don’t drive the staple all the way in,” Cowdrey cautions. “You want room for the wire to expand and contract.” Repeat with each strand, working from top to bottom. “Animals will stick their heads just about anywhere for that next blade of grass,” Cowdrey says, so make sure you add enough strands to stop them (at least eight for goats, at least four for cattle). You know what people say about good fences. Watch the experts teach Andrea Valdez how to build a barbed-wire fence.