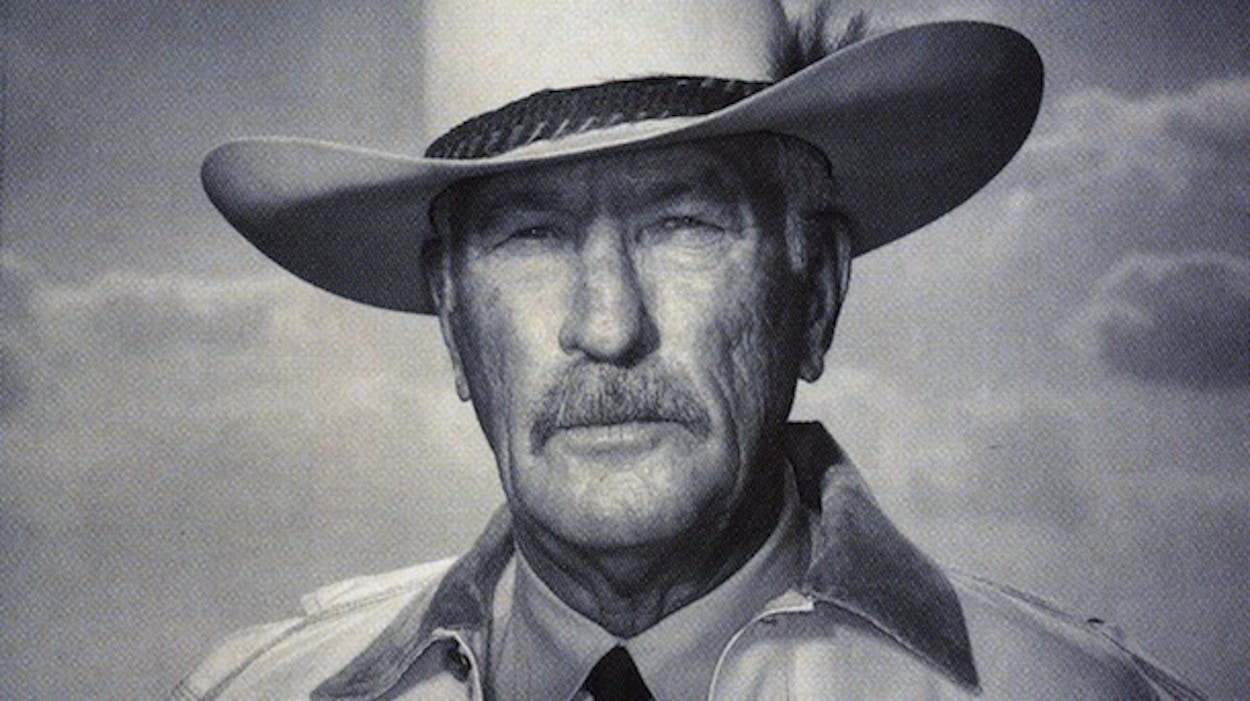

In February 1994 Texas Monthly published an article titled “The Twilight of the Texas Rangers.” It described how the organization’s legendary history and traditions clashed with the changing realities of the modern world, and a black and white photograph of Ranger Joaquin Jackson, taken by Dan Winters, graced the issue’s cover. The image, which evoked a simple place and time, became a poster and, in 1998, the cover of The Pictures of Texas Monthly, a book celebrating the magazine’s first 25 years.

On October 1, 1993, Jackson retired from the Rangers after 27 years of service. He is 66 now and his mustache is peppered with gray, but at six-feet-five he still cuts an imposing figure. These days Jackson is working on his autobiography with author David Marion Wilkinson. With a working title of Only One Ranger, the story will be told in the former lawman’s voice—from the time he was born on his grandfather’s farm in the Panhandle through his Ranger postings in Uvalde and Alpine. Each morning, as he pores over his logs and journals, Jackson relives cases he plans to include in the book—homicides he solved, corrupt elected officials he investigated, even assignments for the CIA.

“The goal of a Ranger is the protection of life and property and the preservation of the peace,” he told me in May as we visited at his ranch-style home in Alpine. “And in doing so, everyone—from the poorest son of a bitch to the richest—must be treated the same.” Jackson said his proudest accomplishment is that he never took a life during his years with the Department of Public Safety. “I feel better about not killing anyone. It’s a better deal.” He is currently serving on the board of directors of the National Rifle Association. “We do not need any more federal firearms laws; we need to enforce the ones on the books,” he said. “My motivation, pure and simple, is the protection of the Second Amendment.”

Jackson now works as a private investigator, and he has also tested the waters of the film industry. His movie credits include Streets of Laredo, Rough Riders, and The Good Old Boys, in which he played a sheriff and worked with Tommy Lee Jones, Sissy Spacek, Sam Shepard, and Frances McDormand. “I told Tommy Lee that I was not an actor, and he said he did not want one—just to be myself,” Jackson said. “He worked with me, and it turned out pretty good.”

Unlike his Ranger days, when he hunted arrowheads to take his mind off things, Jackson now plays golf at least twice a week. He walks to the first tee in a buckskin-colored Resistol complete with horsehair hatband, gripping a Titleist driver in one hand and a cigar in the other.

Jackson and his wife, Shirley, a counselor at Alpine Middle School, will celebrate their fortieth wedding anniversary in October. They have two sons, Don Joaquin and Lance, and two grandsons, Adam and Tyler Joaquin. Lance is a member of the U.S. Border Patrol in Marfa, while his older brother, Don Joaquin, is serving a 48-year sentence in a state prison.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Double homicide—a Marine buddy did the killing. I visit when I can,” Jackson said, his deep voice trailing to a whisper, “but it’s a tragedy in the family.”

As I sat listening to the man in the iconic photograph speak about his life, I was reminded of what those who take pictures for a living say: When an image works well, sometimes you can see beyond the moment. And I realized that the picture of Jackson reflects exactly who he is—a Ranger forever.

- More About:

- Film & TV