The rolling, sparsely populated plains of west Central Texas are not an ideal locale to play a mobile internet game like Pokémon Go. Goldthwaite, wrapped in an early-December mist, offers no cellular data signal whatsoever. Brownwood is spotty. But half an hour north on the road to Abilene, in Cross Plains, population 970, the clouds break and my cell signal returns.

I pull into the gas station next to the Dairy Queen, take out my phone, and fire up the app. To write about John Hanke, the creator of Pokémon Go, I have come to see what his hometown looks like through the window of the game that he designed as a way to get kids off the couch and out of the house.

Hunting Pokémon on foot, I’m the town’s only pedestrian; Main Street otherwise shows no signs of life. Viewed on a smartphone’s screen, however, downtown Cross Plains reveals a fantastic menagerie of creatures from the Pokémon universe. On the sidewalk, I quickly encounter a serpentine Ekans, a mousy Rattata, and an armadillo-esque Sandshrew. A few blocks farther on, at the Cross Plains Area Veterans Memorial, I snare an armored Rhyhorn and a Nidoran—a sharp-eared rabbit with hooves. The memorial itself, with its solemn, chiseled lists of townspeople who served in wartime, doubles in the world of the game as a Pokémon gym, where the creatures I’ve captured in my phone can do battle with digital gladiators left there by other Pokémon Go players. There’s no “winning” Pokémon Go, but gyms like this one are where much of the game’s action occurs. Other, less competitive phases of the game include catching wild Pokémon and nurturing them from unhatched eggs. As a rule it helps for players to get outside and near places where people tend to congregate.

Besides the veteran’s memorial, Cross Plains boasts two other Pokémon gyms, each tied to a site of cultural or historical significance. One is at the First Presbyterian Church, the other at the Robert E. Howard Museum, the early-twentieth-century home of the town’s most renowned son, the pulp writer who created Conan the Barbarian. The game also honors other notable local sites, such as the Higginbotham Brothers department store and a decades-old Dr Pepper mural, with pokéstops, where players can find digital goodies to help them catch, hatch, train, or “evolve” Pokémon.

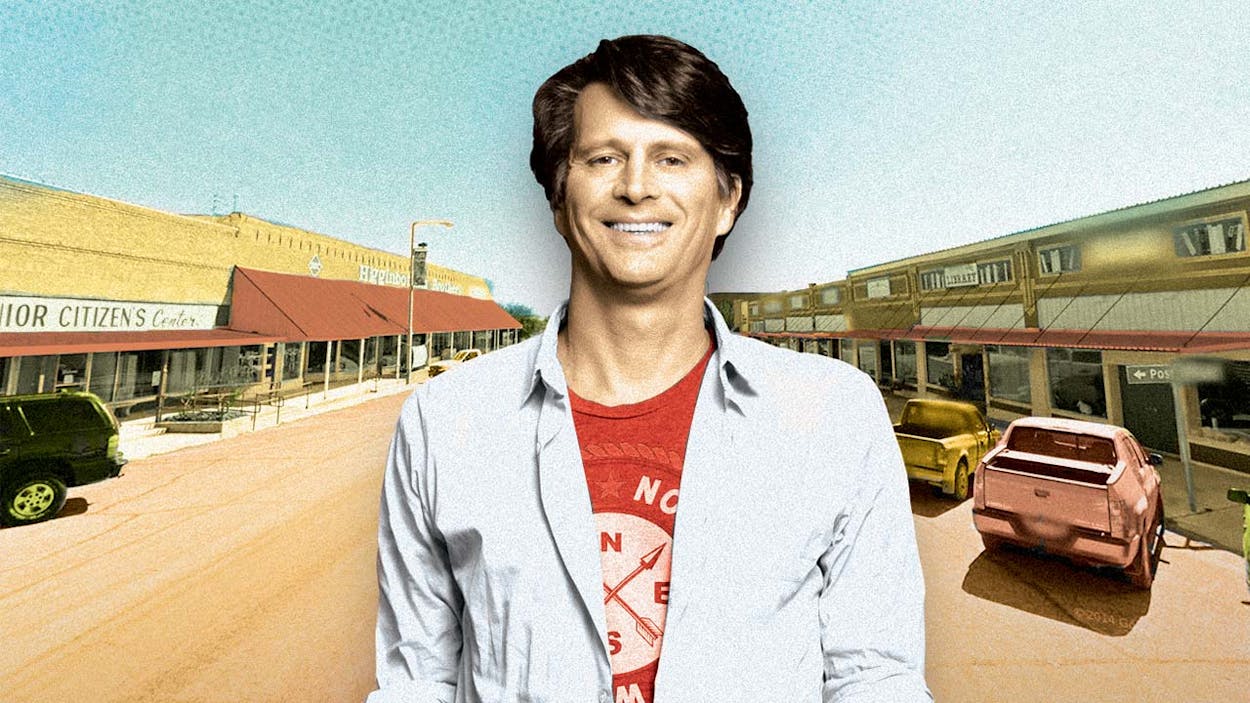

There is, though, one important site in Cross Plains that isn’t marked on the game’s map: Hanke’s childhood home. Last year, Hanke, who is fifty, was hailed by multiple news outlets as a “genius” and “the next Steve Jobs” when Pokémon Go became the most popular mobile game in United States history, exceeding 40 million daily active users within a month of its July launch. More than just a game developer, Hanke is seen as a pioneer of an emerging technology known as augmented reality, or AR, that’s central to the Pokémon Go game-playing experience.

AR relies on technology that Hanke helped create. His 2001 start-up, Keyhole, developed a markup language that enables programmers to write layers of annotation, imagery, or interface over 2-D and 3-D maps. A few years later, as a Google executive, he led the development of Google Maps and Google Earth. If Robert E. Howard put Cross Plains on the map metaphorically, Hanke has done so literally, allowing anyone to view its layout or float down its streets from a computer halfway around the world.

Everyone knows everyone in Cross Plains, and the old-timers I run into during my Pokémon hunt recall Hanke as an intellectual standout from an early age—a “special boy” and an “overachiever.” He was valedictorian of his class of perhaps 21 or 22 students, according to his mother, Era Lee. Says Arlene Stephenson, my tour guide at the Howard Museum, where the walls are covered with Conan iconography, “He left here, and, to me, he just conquered the world.”

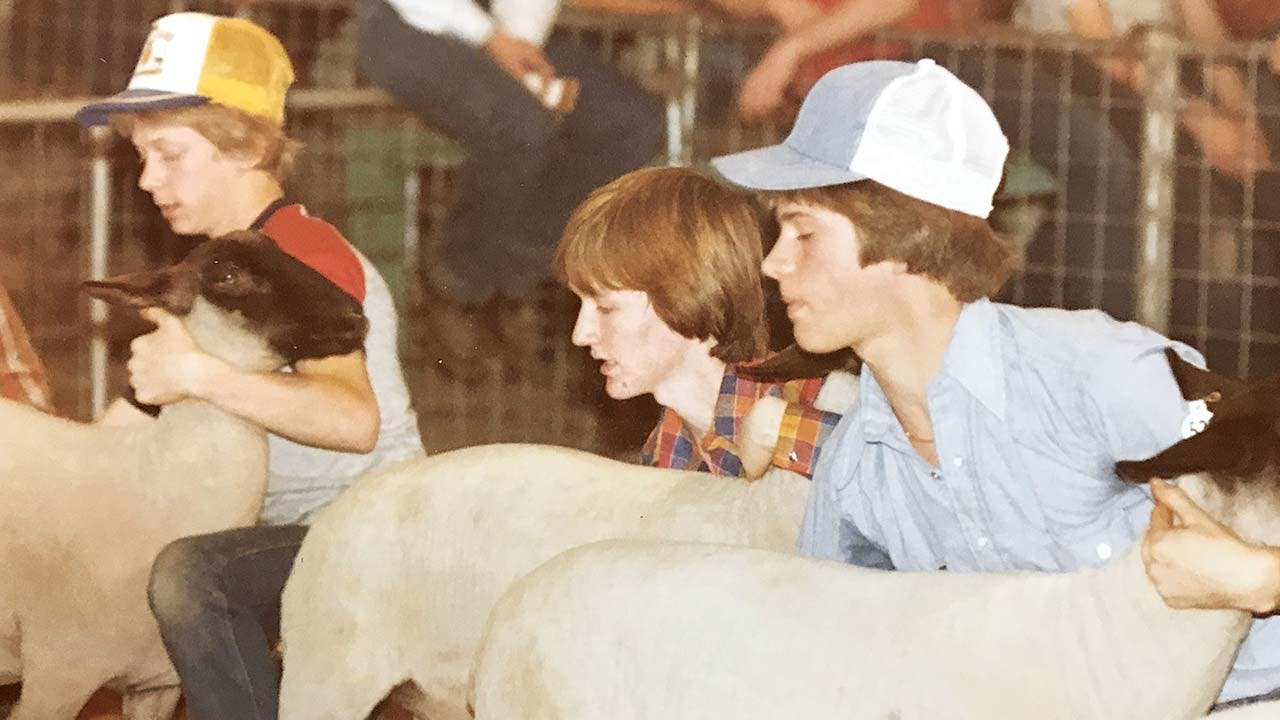

Speaking by phone from his office in San Francisco, where he’s the CEO of Niantic Inc., Hanke says he didn’t completely fit into the small-town world of his upbringing, though on the surface he may have appeared to. “I guess I could say I did the normal things,” he explains. “I played basketball, I was in the band. I was not an outcast hiding in the corner or anything. But I did have this complete other side of my personality. It was kind of pre-internet, so there weren’t too many people to share that with.”

That other side of his personality revolved around computers. Hanke remembers walking past a math classroom in eighth grade and seeing a couple of high school guys playing a game on a TRS-80, one of the first home computers. Hanke wandered in and was quickly hooked. He credits his math teacher Tom Barkley with mentoring him. At one point, Barkley took his students to a computer-programming competition at Baylor University, where they won third in the state. Hanke still has the trophy in his childhood bedroom.

Era Lee has also held on to one of the first computer games Hanke created, a single-screen climber modeled on Donkey Kong that he coded on an Atari computer he’d saved up for by mowing lawns. “That was back in the day when you would send in your code and they would print it in ANALOG Computing magazine and other readers could actually key in your programs,” Hanke explains. “I remember getting a check for two hundred and fifty dollars and being so proud of that accomplishment, going around bragging about it to Mr. Barkley and anyone else who would listen.”

During high school, magazines were Hanke’s only link to a wider community of computer enthusiasts and to news of distant giants like Atari’s Nolan Bushnell and Apple’s Steve Jobs. “This was in an era, I guess not that long ago, when people in [rural Texas] didn’t travel, really,” Hanke says. “I was reading about these things happening in California, which felt like it could have been the moon, this exotic, faraway place I could barely imagine existing, much less think that I’d ever visit. It was the epicenter in my mind—wherever it was, at the edge of the map.”

Upon graduating from high school, Hanke headed to Austin, where he was a Plan II honors student at the University of Texas. He chose to spend his college years immersed in the liberal arts. “The math and the computer stuff was easy for me; it was something I just sort of did on my own,” he says. “It wasn’t something I felt like I really needed to study.”

After college, he signed up for what sounded like the most outlandish opportunity available: a State Department job that posted him to Myanmar, a closed military dictatorship in Southeast Asia. “In my mind, it was like being a crew member of the Starship Enterprise,” he says. “I think if that had existed, that’s something I would have signed up for.”

Around the time of his foreign service, Hanke met and married his wife, Holly, and though she initially joined him in Myanmar, the two eventually decided to build a life and a family together stateside. This led Hanke to business school at the University of California–Berkeley in the mid-nineties, then to a series of gaming and mapping start-ups, culminating in a CEO role at Keyhole, a U.S. intelligence–backed geospatial data-visualization company that was acquired by Google in 2004. Hanke was made vice president of product management for Geo, the department overseeing Google’s Maps and Earth products.

Hanke realized that he’d fully arrived in Silicon Valley in 2006, when an email popped up in his in-box bearing what appeared to be the address of his childhood idol: steve@apple.com. “I remember showing my wife and saying, ‘Somebody’s yanking my chain here,’ ” Hanke recalls. “I said, ‘There’s no way I believe this is the real Steve Jobs, but I’m going to reply and tell him I’m free to talk tomorrow, just to see what happens.’ I did that, and my phone rang the next day, and it was him. He made this very opaque pitch about this device that they were working on and how they really wanted to put Maps on it.” The device in question was the original iPhone. Hanke would help lead the charge to get Google Maps ready for mobile use. (Jobs may have come to feel that Hanke did his job too well, given that Google Maps is widely regarded as superior to Apple Maps.)

Throughout his six-year tenure at Google Geo, Hanke was always thinking about the gaming implications of his technology, and by 2010 he was finally ready to return to game building. He considered launching a start-up, but Google’s top brass agreed to create a start-up-like environment within the company for his new effort, Niantic Labs. In the seven years since, Niantic has gone from an unknown with one relative flop, the Field Trip app, to minor notoriety with the cult-hit mobile game Ingress to, with Pokémon Go, a success so enormous that, to discourage overeager Pokémon hunters from banging down the doors, the company has removed its name from the office building it calls home. In the meantime, Niantic has been spun out of Google, with Nintendo as a major investor. Niantic’s financial information isn’t public, but when Pokémon Go launched last July, Nintendo’s stock valuation surged by about $12 billion.

Hanke has come a long way from Cross Plains, but he hasn’t forgotten where he came from. In fact, he has held on to his family’s small ranch outside of town and frequently visits Era Lee, now 87.

Cross Plains today is still the kind of town where you can walk into the senior center at midday and find the mayor, Bob Kirkham, shooting the breeze with a past mayor, Ray Purvis, over lunch. Like many small towns at this longitude, the demographics skew a bit older than the national average: in Cross Plains, nearly a quarter of the population is older than 65; nationally, it’s more like 15 percent. Most folks seem to have never played Pokémon Go. They’re likely to refer to smartphones and mobile devices as “computers.” One person calls the slashes, braces, and pointy brackets of programming languages “those funny things.”

Hanke did get to see his two worlds come together in 2013, when Niantic hosted a global meet-up of Ingress players in Cross Plains. He timed it to coincide with the town’s annual Robert E. Howard Days weekend, when dozens of Conan fanatics descend on the town. Even so, the Ingress players stood out. “I was riding with the police at night,” Purvis recalls. “People were calling in, wanting to know what was going on. It was crazy! People down in the park at midnight.”

Ingress is similar to Pokémon Go in many respects. It involves a game world layered over the real world, with important locales for game play associated with cultural and historic landmarks. The world of Ingress is a zero-sum battle for supremacy between two teams, the Enlightened and the Resistance, who duke it out for control of turf and resources. Upon downloading the game, users are required to pick a side. The mythology of Ingress hinges on an alien technology that has been loosed upon an unprepared humanity; one side trusts the technology unquestioningly, and the other is fighting for what might be called civilian control over it.

When Hanke plays Ingress, he sides with the Enlightened, or the techno-skeptics. “The Enlightened aren’t necessarily totally anti-technology, but they’re sort of humanists,” explains the former liberal arts major. “Their philosophy is ‘Hey, you’re a human being. You aren’t meant to just exist in some purely digital substrate. You’re meant to be out in the world. Walk around, soak in some sunshine, fully experience being a human being.”

Hanke’s game-world affiliation with the Enlightened reflects values he picked up in Cross Plains as a kid. He happily recalls youthful days spent shelving books and chatting with the town’s longtime librarian, Billie Ruth Loving, who helped foster his interest in books and culture. (Loving is long deceased, but I came across a plaque bearing her name in the new children’s wing of the library while hunting for a pokéstop near a bust of Edgar Allan Poe.) Along similar lines, Hanke’s late father, Joe, served as the town postmaster while also running the family ranch. These days, Hanke is an outspoken advocate of getting outside by any means necessary.

Hanke has tried to encourage passions for culture and the outdoors in his own children, now eighteen, sixteen, and ten. Early on he came to see computers and video games as, at best, an unsteady ally in the struggle to raise active, curious kids. “Steve Jobs and Nolan Bushnell and the other Silicon Valley pioneers did too good a job of building these incredibly rich screen-based experiences,” he says. “It’s like sugary breakfast cereal. You throw that into the mix, and naturally that’s what your kids want all the time.

“I’m not a Luddite,” he adds. “It’s not that I didn’t want screens in my home. There’s so much they can do for us, even for the kids’ development. The thing that had initially drawn me to computers was walking past a classroom and seeing these guys playing the Star Trek game on the TRS-80. Games as an entry point to technology, programming, and all the positive things that come from developing that skill set, I could see. But I was struggling with also wanting to get my kids outside.”

Hanke now describes Field Trip, his first app with Niantic, as coming from “the high school librarian side of me.” The program aspired to comprehensively catalog historical and cultural sites of interest and alert users anytime they drove or walked near one. He developed the idea, he says, on family road trips, when he’d see signs for historical markers whiz past and wonder what he was missing. Field Trip managed to build a deep catalog of sites, but it never caught on with a broad public. “It didn’t have that virality,” Hanke admits. “It wasn’t something my kids were particularly into.”

Ingress aimed to fix that. “The pivot was, how can we create a compelling outdoor experience that has those same sugar-coated-breakfast-cereal addictive qualities but is wrapped in an experience where you’re outside, seeing new places, getting exercise, talking to real people in real life?” Hanke says. “You lure people in under the auspices of this sci-fi game. But you show up with your kids, and, oh, there’s a historical marker there. Oh, this is a stop by Ulysses S. Grant when he traveled through Texas. Or this is a ship buried in downtown San Francisco.” (Niantic takes its name from a nineteenth-century whaling vessel that was eventually consumed by the city as San Francisco infilled its harbor.)

Ingress was a cult phenomenon, but it attracted one important fan: Tsunekazu Ishihara, the head of the Pokémon Company. “Our pitch meeting was just a sort of mutual lovefest,” Hanke says.

As Pokémon Go launched in America, Hanke was on vacation in Japan with his oldest son, who was about to leave home for college. They’d planned the trip together months before the game’s launch date was set, and Hanke decided to go through with it even though he might miss the biggest moment of his professional life.

Hanke describes following the game’s viral explosion from afar as surreal. He recalls walking in a bamboo forest in Kyoto with his son while the gravity of Pokémon Go’s success was just beginning to sink in. “We were walking in this very serene, otherworldly place, and meanwhile I’m getting updates on my phone, Jimmy Fallon’s talking about Pokémon Go, and all of that craziness,” Hanke says. “It was strange for it to happen, but it was even weirder, I think, for me to experience it remotely. It wasn’t yet launched in Japan, so I was hearing about it from the internet and from texts coming in from my wife: ‘You’re not going to believe this. People are all over our downtown playing Pokémon Go.’ ”

With Pokémon Go, Hanke has realized his dream of a viral, addictive game that helps kids get outside and appreciate their physical and cultural surroundings. When he returned home from Japan, Hanke saw the benefits firsthand with his youngest son. “There was a point when he was literally begging my wife or me to take him outside. He wanted to walk five kilometers early one Sunday morning, because he wanted to hatch a Pokémon egg,” Hanke says. “That was a moment when I was just like, ‘Victory!’ ”

What follows a life-altering success? While Hanke is reluctant to get specific about his next projects, he’s excited to talk big-picture. In augmented reality, Hanke sees the potential to create a new user interface for the world. “With AR you can paint the physical world with this interactive, two-way interface that can give you information about the status of every physical thing that you’re passing by or interacting with—and let you book it, schedule it, buy it, or learn about it,” he explains. “That’s the ultimate vision that gets me excited.”

Hanke’s vision is in step with what observers expect to see in the near future from companies like Google, with its nascent AR platform, Tango. “I’m very positive on the future of this marriage of the physical and the virtual,” says Brian Blau, an analyst with Gartner, a leading technology research and advisory firm. “Pokémon Go will be remembered as the game that helped promote the technology.”

Though Hanke identifies as a techno-skeptic, he can sound like a no-holds-barred advocate when discussing AR. He vehemently disagrees with the suggestion that AR only deepens the hold of digital technology on our lives, arguing that it instead encourages us to interact with the world and with other people in real space. He speaks of people who have overcome depression, lost weight, and met new people by playing the games he’s created. “The digital part is the carrot,” he says, “but the real payoff of the game is the physicality of it.”

In all my Pokémon-hunting around Cross Plains, I never saw another person playing the game, though no doubt players have been there. Creatures belonging to users with names like Jazzie6114 and Bucks43 control the local gyms and beat back my attempts to conquer the realm, Conan-style, as a Pokémon outlander. I begin to wonder about these anonymous adversaries, names chiseled in virtual stone. Are they the real object of my search? Is one of them actually John Hanke? Or, more likely, a kid from down the dusty street who might someday grow up to follow in Hanke’s footsteps?

I ask Hanke what he hopes a kid like himself, living today in a dot-on-the-map town like Cross Plains, would discover in a game like Pokémon Go. He’s already told me that Robert E. Howard was an inspiration to him as a young man. I expect him to say something about his game’s offering broader horizons, fantastic vistas that encourage kids to dream. But his answer is almost the opposite.

“I would hope that it would help them appreciate the interesting stuff that is in that town and in the nearby towns that they may view as boring when they’re imagining their future life in Austin or New York or wherever,” he says. “The opportunity of the game is to turn you on to the cool aspects of your community wherever you live and to give you a way to enjoy that. There’s nothing wrong with dreaming of the place you’ll end up. But it’s also great to appreciate where you came from.”

Austin writer Michael Agresta’s work has appeared in Slate and the Wall Street Journal.