In my neighborhood, I’ve always done a lot of walking. I walk in the morning and late at night with my husband—John marked out a mile some years ago and likes to stick to the same route—and often in the afternoon. Our dogs are frequent companions. I would like to tell you that this activity has become my daily meditation, one that has taught me about living in harmony with my surroundings, but anyone who has seen me trying to corral two stubborn and erratic golden retrievers would know that isn’t true.

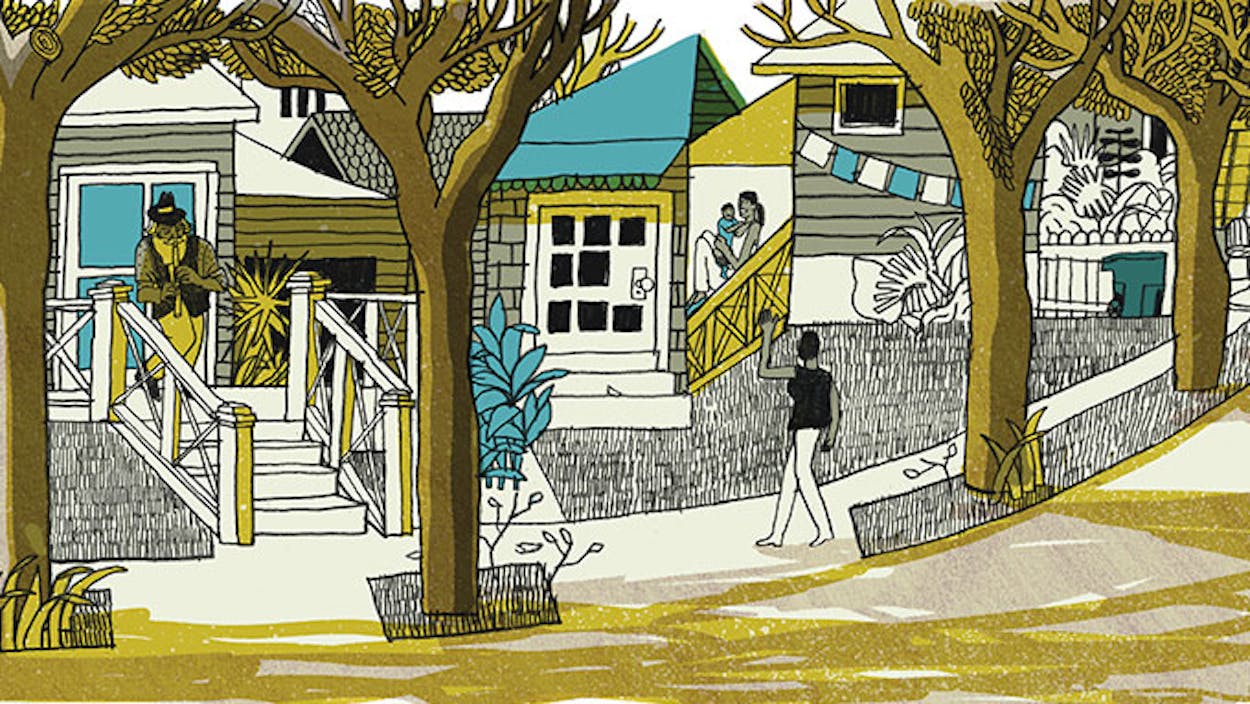

Instead I think of these walks as an opportunity to secure the perimeter of my domestic life. When we first moved to this inner-city Houston neighborhood, Woodland Heights, 25 years ago, I was particularly fond of the elderly women who sat on their porches all day or devoted hours to sweeping the leaves from their curbs. Like them, what I felt was pride of place. It was in those early days that I developed an appreciation for the more creative gardens in the neighborhood, like the collection of cacti that took up an entire lot and the few near-perfect replicas of English cottage gardens fashioned with purple iris, sage, rosemary, and other native Texas plants. These days I check on my friend Marci’s ornamental cabbages and bottle trees and my neighbor Joan’s collection of edible greens, which often make their way into my white bean and sausage soup.

On the surface, there’s a soporific sameness to these walks. Mornings we see families trotting to school and moms racewalking after drop-off. Nights are more sociable, particularly among the childless dog-walkers: we fall into step with the owners of Copper and Bella and Putty and Smokey, slapping at mosquitoes in the thick summer air or stamping our feet on chilly winter nights as we discuss the news on the neighborhood website—sometimes about crime, usually about lost pets—and gossip about bungalow warts, the local moniker for bad remodeling jobs.

In other words, nothing seems to happen. Except that, imperceptibly, our route offers a series of associations that are always fading in and out: I see our grown son, Sam, splashing at age five in Marci’s pool, where she taught him to swim; I wonder how Joan’s cancer treatment is going. Here is one of Sam’s kindergarten classmates back from Spain, more beautiful than ever; there are the night herons, nesting again in the oaks on Bayland Avenue, just as they have every year since we arrived, in 1989.

It’s a little like dreaming, these daily walks. I live and relive, reorder and reset our lives in probably a hundred different ways, until we are back at our front door again. Twenty minutes, three or so times a day—when you have lived in one place as long as we have, there’s a lot to process.

I first discovered Woodland Heights just as I was leaving Houston for a job in Austin in 1984. I had moved to the city straight out of college in 1976 and occupied a succession of semi-seedy apartments in the Museum District, oblivious to the roaches and the misfits because, like everyone else, I was just passing through. Then, before my actual departure, I staged several valedictory tours and happened to follow Montrose Boulevard north as it changed names—from Montrose to Studemont to Studewood—and discovered a postage stamp–size neighborhood just east of the famous Houston Heights, which both Dan Rather and serial killer Dean Corll had called home.

Like its sister neighborhood, Woodland Heights offered a mixture of sixties-era funkiness and East Texas flintiness. The streets were lined with Craftsman bungalows and lacy Victorian cottages, only a few of which had enjoyed a restorer’s touch. In a nod to one of Houston’s far better neighborhoods, live oaks lined the main drag, Bayland Avenue, their branches intertwined overhead like clasped hands. A convenience store—the One Stop or the Stop One, hard to say from the sign—sat smack in the middle of the neighborhood, and the largest house, once the mansion of Woodland Heights’ developer, was then a halfway house for parolees and the mentally ill, a bad combo by just about anyone’s standards. There were a lot of snarling chow dogs living behind cyclone fences, some hand-scrawled No Trespassing signs, and some pretty good Tex-Mex restaurants on nearby North Main. Larry McMurtry’s used bookstore, Booked Up, and a small plant nursery passed for retail, along with some excellent junk stores a bit farther north. “Could any place be more perfect?” I thought. What a shame to find home just as I was leaving it.

Five years later, after marriage and a move to Dallas, my husband was offered work back in Houston. Of course, I knew exactly where I wanted to live. The neighborhood was mostly unchanged; the residents were still a marginally friendly, mildly suspicious mix of white-haired widows and widowers, Hispanic families, and eccentrics—like Richard, who wore his hair in an Elvis pompadour in front and a long braid down the back and, for reasons no one cared to investigate, lived in a shack behind his mother’s bungalow; or the two aged sisters who never seemed to use electric lights; or the guy with a quizzical smile and dyed black hair who pedaled about on a very large tricycle. The paleta men came through every day after school was out, selling cantaloupe and watermelon popsicles to the children of interlopers who’d moved in seeking refuge from the suburbs.

In other words, Woodland Heights was an old, mostly blue-collar neighborhood that was just on the cusp of gentrification. It took me a while to downshift from our life in Dallas; in one of our first weeks in town, we were invited to be part of a dinner party in which each family on our block was to serve a course in their home. I spent as much time on the flower arrangements and napkin-folding as the salad I had been assigned, and I could see from the dubious looks of our new neighbors that maybe I had tried too hard. Within months, though, I had adjusted to the groaning buses on Bayland and the occasional sound of gunshots in the night. One day, as I sat at my desk, I watched a man break into the house across the street and stroll away with my neighbor’s VCR in his arms. I reported the crime and a few months later was afforded my first-ever opportunity to pick someone out of a photo lineup. It was great to be back in Houston.

We have lived in Woodland Heights ever since. When the landlords apologetically raised our rent on their restored Victorian from $900 to $1,200 a month, we bought a two-story, decidedly unrestored frame house two blocks away that was built, according to vague and contradictory city records, in either 1902 or 1912. A few days before we closed, I sat on the front porch swing, my bare feet brushing the floorboards, and knew with a certainty I’ve rarely experienced that I had found my place in the world, even though at $150,000 it came at some cost. We have been here from the time Sam was six months old, and we’ve stayed through his graduation from college, the death of my husband’s parents and my mother, and the loss of one beloved dog, several cranky cats, and two short-lived goldfish named Toby and Lucky, who are buried somewhere in the backyard. From this single base of operations, we have witnessed the Gulf War, NAFTA, and O. J. Simpson’s trial; Bill Clinton’s reelection and the Monica Lewinsky scandal; the planes hitting the Twin Towers; Hurricane Ike; President Obama’s election; and the forever wars in the Middle East. We have been here long enough to have paid off our mortgage, and long enough to begin to worry about how we will pay our property taxes when we retire.

For a quarter century, while the world has spun, I have stayed in one place, and if I have learned anything from that experience, it is that being firmly rooted doesn’t have anything to do with standing still.

The playground at Travis Elementary is ringed by cypress trees that in the spring turn a rich, glorious green, creating shade for the children whose high-pitched voices I hear on the days I work with my windows open. I know the trees well because we helped plant the saplings when Sam was a baby, carting him to the campus in a carrier. I used to know which tree was “our” tree, but now that they all soar fifteen or so feet I’ve lost track, just as I often fail to recognize the kids Sam went to school with when they greet me at Target or Kroger.

“A baby belongs to the world,” my friend and neighbor Karla told me soon after Sam was born, in 1991, a casual remark that would turn out to be indisputable. I liked to rock him on our porch swing, waving silently to passersby who knew the penalty for waking a sleeping child, or wander the streets with him in the stroller, coveting renovations we could not afford and gardens I had no time or gifts to imitate. But it was the school that became the locus of our lives five years in. John and I were both enchanted and enervated by the idea of parenthood: we listened to intelligence about teachers, we bought $25 personalized bricks to pay for renovation projects, and we joined a growing population of mothers and fathers who willingly sweated over the hot dog booth at the fall carnival. Our new narrative no longer involved staying up to drink wine and watch Twin Peaks but instead demanded our presence atsolicitously nondenominational Christmas pageants. Outside of school, we set out luminarias for Lights in the Heights, a small neighborhood fete that included performances on front porches by five-year-old ballerinas, a Swiss bell-ringing society, and, if memory serves, someone who played carols on a glass harp.

Yes, this world was corny, and utterly lacking in opportunities for career or social advancement, and that was why I loved it so. My life took on a form and pattern honed by a particular place, the cycle of school and child-rearing and the natural world around me: the blooming of the azaleas in March, followed by spring break; the end of school, followed by the Hartzells’ Fourth of July party; the appearance of caterpillars who feasted on the leaves of my citrus trees, only to reward me with their astonishing butterfly wings a few weeks later in the same way one kid or another made the passage from training wheels to a bike. A bad day could be cured by turning my car onto Bayland just in time to catch the low sun rays cutting through the oak branches, a Woodland Heights version of stained-glass windows.

I do not know when or how I came to understand the restorative qualities of such things, but I did, so much so that when my husband came home one day with a job offer in Seattle, I was horrified. Looking back, I’m still sort of mystified by my objections—it was Seattle, after all, not Trenton or Detroit, and the job benefits included free health insurance and stock options. Instead of being excited, though, I cried a lot in favorite neighborhood restaurants and worried aloud about moving a child during a formative period. But I knew that my inability to leave really came down to a question of identity: I had tied mine not just to Houston but to a particular part of Houston. I wanted to watch Sam and his friends grow up here, to see how their stories turned out.

When we moved in, just a few houses in our neighborhood could rightfully be described as fancy. Renovations tended to be modest and ongoing, the journey being more important than the destination and all that, a nice way of skirting the issue that no one had much money. But around the time Sam was in high school—the same time a neighbor suggested he didn’t need us to walk him to the bus stop anymore, a fact Sam had been making clear by walking eight feet ahead of us—the McMansions began to appear. They weren’t on the scale of their River Oaks or West University counterparts, and the developers even took a stab at mimicry with Victorian-style turrets or Craftsman-style shingles. Residents didn’t like them, but no one paid them much mind either. The house that did drive people into fits of architectural rage on our neighborhood website was a small brick contemporary; despite Woodland Heights’ reputation for tolerance, ersatz clearly had something on novelty.

But then there seemed to be more and more supersized Craftsman cottages, with price tags that seemed, well, startling. Houston developers were suddenly taking another look at Woodland Heights, which was eight minutes from downtown and, for better or worse, convenient to two major freeways. Those two-bedroom-one-bath bungalows that had once belonged to young families started getting empty-nester makeovers, complete with open floor plans and Jacuzzis. The old halfway house was bought and remodeled by a local realtor and his partner, who restored it within an inch of its life and then invited the neighborhood in to gawk. This we did, and more; on weekends my husband and I would grow red-faced as we ran into other old-timers snooping in closets of homes that had gone from $70,000 to $350,000 to $500,000—a bargain!—in little more than a decade. I was stunned in 2009 when we got our property assessment and our home had doubled in value; I was, after all, still pulling pans off of sagging fiberboard shelves. Envying my rich new neighbors, I developed an irrational desire for a sprinkler system; the day my husband told me that his late father had left him enough for a kitchen renovation was one of the happiest of my life.

The strange confluence of wealthy consumers and relatively cheap commercial real estate also meant that it became possible to buy locally roasted coffee, artisanal cheeses, and locally sourced pecans without leaving Woodland Heights. It was a little embarrassing when Target was allowed to settle nearby, but bitter protests erupted when Walmart followed. “Heights, we love you,” wrote the Houston Press after quoting a resident’s precious remarks about local coffee bars, “but sometimes you need to take it down a notch.”

What had happened, of course, was that the class war had come to our neighborhood, pitting people in the shrinking middle—people like John and me—against those with less and those with, well, more. “If you don’t like it here, go back to West U” became a snide rejoinder to newcomers demanding permits for two-story garages. Lights in the Heights morphed into a marketing campaign for realtors, complete with corporate sponsorships and far too many oldies bands singing “Louie Louie.” The bell ringers, it appeared, had been exiled to the Alps.

Among longtime residents, there was a growing sense of loss. It wasn’t that we were trying to preserve our New York Times–reading, we-always-recycle ways—well, we sort of were. But we were also trying to save something else: the ability of a mix of people to live peaceably in one place, something that had become a rarity not just in Houston but virtually everywhere else.

Oddly, a successful effort to convert Woodland Heights to a historic district a few years ago slowed the move toward civil war. The rules for new construction and old renovation scared away some of the developers, though it also brought out the ire of the old-timers (“You mean I have to get permission from the city to put a damn ceiling fan on my porch?”). Still, you can now look down streets like Bayland and see a consistent row of sweetly restored cottages—even if they have giant additions popping out the back.

Sometime after Sam left for college, four years ago, all the old dogs began to die. The math was predictable: many families, including ours, had bought pets for their five- or six-year-olds around the same time, hoping to teach them something about responsibility. Lucky, two Sams (no relation), and our dog, Chuy, became local celebrities on their walks, at first bounding ahead and then, in later years, struggling on arthritic legs to keep up. When Chuy became too ill for nighttime walks, my husband took up the tin whistle as his partner and, white-haired and white-bearded and wearing a battered cowboy hat, became known to newer residents as the weird old guy who played the flute in the dark.

It occurred to me, sometime in my fifties, that I had once known all the babies, and then all the dogs, and then, well, I had become something of a stranger in my own neighborhood. I can’t say I was sorry to be done with the all-consuming near hysteria of child-rearing, but I was wistful when the kids I had read Charlotte’s Web to at Travis so many Friday afternoons ago started coming home with impressive degrees and admirable careers. Older residents, like Mary Pat, who had been a barmaid at Griff’s Irish bar and had one of my favorite gardens, also began to disappear, as illnesses and general irritability got the better of them. Richard, the man with the Elvis pompadour, sold his mother’s house for what must have been a substantial sum and spent his last days on the property arranging chairs and tables in his driveway, for guests who never came. I thought of the assembly as the Ghost Bar.

But there was always some reason to feel that the neighborhood—the one I knew—would never disappear entirely. A few years ago, new neighbors moved into the house across the street, the one I still describe as Farnam and Melanie’s, even though two other couples have lived there since them. James and Diane have a little girl named Ellie, who quickly overcame her shyness and started dropping in to play with our newly acquired puppies, dismissing her parents until further notice. Ellie has a mop of black curls, an assessing smile, and a belly laugh as contagious as a summer cold. I flinched just a little when Diane suggested that John and I were her “honorary grandparents” but soon accepted the charge, inviting Ellie to artisanal hot dog lunches and reminding her to say thank you.

Now Ellie often comes along on our afternoon walks, and while I struggle with the dogs, she runs off in her intentionally mismatched socks to pick blooming jasmine and the occasional stray bluebonnet. I weave the flowers through her hair before sending her home, just as the light begins to fade.