Few writers are as revered in their homeland as Larry McMurtry is in Texas. The Archer City native wrote some of the state’s most heralded fiction, including The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment, and, most famously, Lonesome Dove.

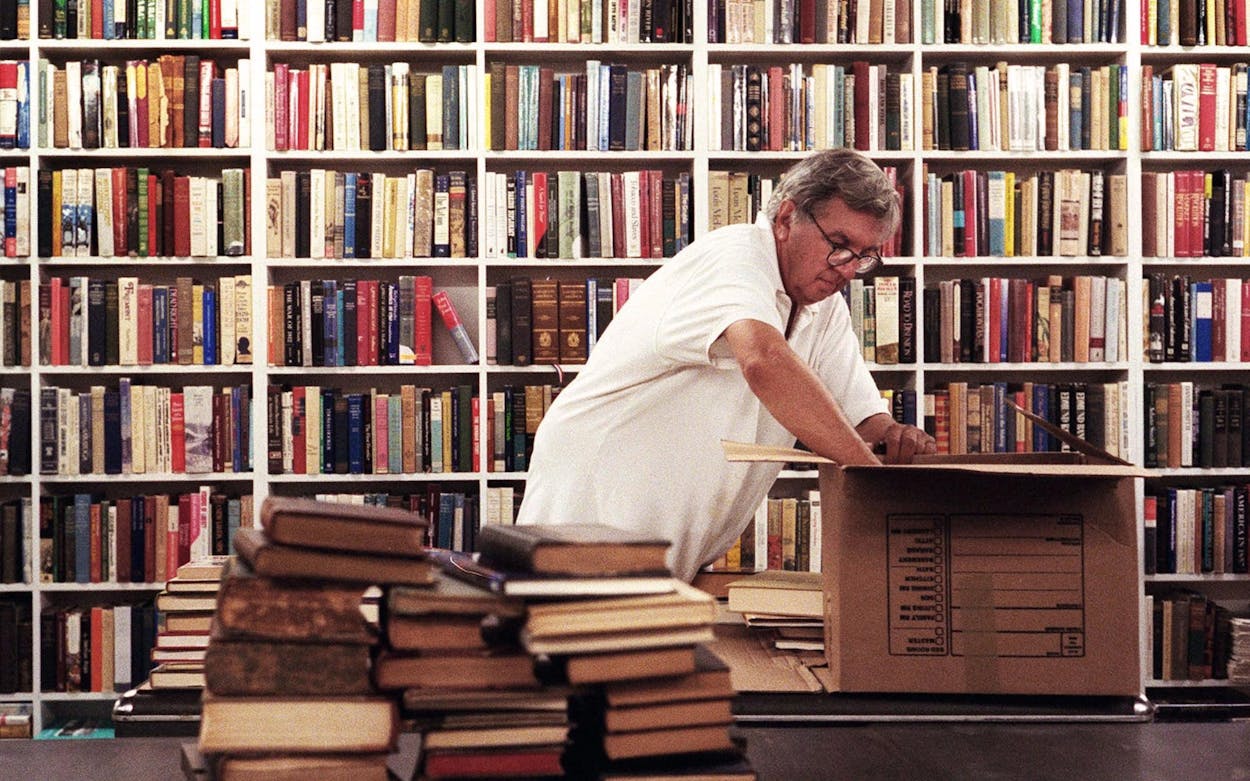

McMurtry is now on the right end of the bell curve of life. Last summer he emptied out three of his four bookstores in his West Texas hometown, a sell-off that signaled to many that he was looking to tie up loose ends. But preserving his legacy has been a decade-long project for George Getschow, the writer-in-residence for the University of North Texas’s Frank W. Mayborn Graduate Institute of Journalism. To that end, Getschow, along with a group of grad students in his Archer City Writers Workshop, recently launched Center and Main, a website dedicated to collecting “Stories from the Heart of McMurtry Country.”

On Friday the site will publish a long interview with McMurtry that Getschow and his grad students conducted earlier this year at McMurtry’s last store, Booked Up No. 1. The conversation touches on the “twilight” of McMurtry’s career, the future of books (particularly Westerns), and the writer’s favorite television shows (which will likely surprise you). A preview is excerpted below, and the entire 5,300-word will be available to read on Center and Main’s site tomorrow:

George Getschow: Why do you call yourself a “minor regional writer”?

Larry McMurtry: Because there might not be anything out there that’s not minor. In fact, sub-minor is what a lot of it would be. Understand that in the silver light of history almost all writers are minor. A generation just passing might produce five writers that are not minor, might not produce but two or three. I think when you boil down the Mailer-Roth-Bellow generation, there’s not much, really, that I wouldn’t call minor. I think Flannery O’Conner has the clearest claim to be more than minor. She was a great writer.

Bill Marvel: What about Cormac McCarthy? You didn’t mention him in the pantheon.

LM: I think that his early books are not very good. His great book, if he has a great book, is Blood Meridian, but I’m not sure it alone lifts him out of the category of being a minor regional writer. I like, for myself, No Country for Old Men better than Blood Meridian. I think Blood Meridian is a little windy. It loses focus sometimes, although I admire it. And the great passages in it are really wonderful.

If I had to point to two books that might lift me out of the minor catalogue it would be Duane’s Depressed and Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen. I think those are both really good, really, really good books. A lot of the rest of them are good, but they’re not earth-shaking. It’s okay to be minor. In fact, if you can be minor you’ve made a considerable achievement, because most people don’t register on the scale of minor or major at all. So I’m not worried about it.

GG: You’re one of the few Texas writers who’s looked at the state unsentimentally.

LM: That is true. I’ve tried as hard as I could to demythologize the West. Can’t do it. It’s impossible. I wrote a book called Lonesome Dove, which I thought was a long critique of western mythology. It is now the chief source of western mythology. I didn’t shake it up at all. I actually think of Lonesome Dove as the Gone With the Wind of the West.

BM: What is the fate of writing about the West and of books? And do you fret about these things that are disappearing?

LM: You bet I do. I fret about these things that are disappearing. I don’t know that the western is. But I’ll tell you what. If anything has destroyed the western genre it’s The Legend of the Lone Ranger, which I wrote the first script for twenty-six years ago. $375 million it lost. Who knows when they’ll make another western. But I don’t think the western as a genre is gone. We are working on a couple. And I’ve written another novel that’s a western and it will be published in the spring. It’s still there.

But the big, big, big changes. I’m having a conflicted tussle with Amazon because what they’ve done to the book business is horrible. It’s just horrible. It’s destroyed conventional publishing. As much as I hate them, they came to me the other day with an offer to make a pilot that Diana Ossana and I wrote five years ago. And it drifted around. It went to HBO, they got it and paid for it and then they put it on the shelf. It went to 20th Century Fox and they put it on the shelf. Amazon wants to do it and they have the moxie to do it. They have so much money it’s incredible, and they can do whatever they want to do. They released fourteen pilots to the mainstream in a week. Nobody else can do that.

What I see is everything has become television. Television is smarter than movies, it’s infinitely cheaper than movies, it’s more flexible than movies. I think of the major stuff that’s come out on movies and television, say, in the last decade. Something like Everybody Loves Raymond and The Sopranos. They’re great series, you know?

GG: I’m intrigued that your last book was a western about Custer, and you said you’re coming out with a book in April that is going to be a western. It sounds as if you believe westerns are going to be around for quite a while.

LM: Oh, I do. I don’t think you can sink the western. Well, Custer is a flash point with me. It wasn’t at all what I intended. I intended to write a companion to my Crazy Horse, a short biography or something like that. I never intended for it to be a coffee table book with hundreds of photographs. There was a change of executive structure at Simon and Schuster. The new person didn’t want it, and so they held it a year and a half, they tarted it up with all those photographs, and I’m very disappointed in it. But that doesn’t mean the end of the western. There will still be westerns.

Amy Burgess: You’re one of the few writers who’ve had equal success in the different genres, with TV and movies and books. Which ones get you the most excited when you have a new project that gets picked up?

LM: They’re so different, it’s very hard to compare them. I’ve written thirty-two novels. I can’t say that I get excited when I start to write a novel. I get to work, but it’s not a daily thrill. And neither is working in movies. Working in movies has become harder and harder and harder. I’ve had three or four very successful movies. Average time on making those movies was ten years. Ten years to make Terms of Endearment, ten years to make Brokeback Mountain. It doesn’t come quick. You have to get the money. and to get the money you have to get the actors that can bring the money. It’s very slow.

We have several projects right now that I don’t understand why nothing is happening. Two years go past, no checks come in the mail. It just sits there. We have a project with Ridley Scott right now that’s set in this part of the country. So, there are stories out there. But it’s really, really hard to make westerns. The thing that’s so hard about it is that they involve animals—cattle, buffalo, horses—and animals are so expensive. The reason it’s more likely to happen on television—the reason Lonesome Dove was on television instead of film—is that it’s so much cheaper. It’s all about money.

AB: Would you ever self-publish?

LM: Yeah, I was just about to self-publish this weird little novel, then somebody bought it, strangely enough. To my intense surprise. Someone bought it and saved me the trouble.

Harry Hallall: Why were you going to self-publish?

LM: My own publisher had been so negative about it that I thought, ‘Maybe they’re right; maybe it is awful.’ Then two years passed, and I got it out and read it, and I rather liked it. I told the agents to say bye-bye to Simon and Schuster and shop it around a little bit. It sold instantly.

It’s an end-of-the-West western. Most of the westerns that you read or have read are end-of-the-West westerns. This one is just a little more clearly an end-of-the-West western. I felt that there were stories and people like Charles Goodnight, people like Wyatt Earp, people like Buffalo Bill, that could use a little coda of some kind, one more pass. So I did it. I think it’s pretty good. I don’t think it’s a world masterpiece, but it might be. You never know for sure.

HH: What authors have you enjoyed reading, or what works have you really enjoyed reading recently?

LM: I’ve reached an age in life when I read very differently. Mostly I’ve read for adventure. Now I read for security. Which means I reread almost entirely. If I get sent a book that I have to decide whether to try to do the script or something like that, I read it. But for myself I read two authors over and over again. Robert B. Parker, the mystery writer from Boston, and an English aesthete named James Lees-Milne. He left a twelve-volume diary that is one of the treasures of twentieth-century English literature.

GG: One of the things that distinguishes you from any other Texas writers is courage. You took on the nostalgic writers like J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb. And even though you respected their work you also found their work far too sentimental for the reality that you saw before you. You were skewered in some circles for doing that, and yet you did it, and I know that, I’m sure there were costs involved.

LM: I think I just am better informed. Look at all these books. I have 28,000 books in my home. Most of which I’ve read or at least considered. That’s what I’ve found lacking in Texas literature, and I said it. They haven’t read enough. They haven’t traveled enough. They haven’t seen enough of the world. Gary Cartwright and Larry King and Ronnie Dugger, and a whole gang of quasi-journalists, quasi-writers around Austin. Bill Brammer occasionally wrote really pretty good stuff, but few of them really sustained it. So I was asked to make that speech at a Fort Worth museum, and it caused a little stir.

I like literary controversy. There’s not enough literary controversy in Texas. Needs to be more.

BM: What would you tell young aspiring writers about reading—the importance of reading, and what to read?

LM: I’d tell them that the most important preparation for writing is reading. Certainly for me and most people I know. Trying to imitate the writers that we love to read. That’s what got us all started.

BM: But you have to read a lot before you find those writers that you want to imitate, I would think.

LM: That’s fine. It doesn’t hurt you to read a lot. In fact, it’s better that you read a lot. You’ll find the right ones.

Matthew Jones: I wondered if you could expand on that a little bit. Earlier you were saying that television writing is booming. I’ve noticed that there are shows like you mentioned, Everybody Loves Raymond, The Sopranos, that are essentially visual novels.

Larry: They’re like the nineteenth-century novels. They satisfy the same appetite for narrative and family life. The backbone of the nineteenth-century realistic novel is the family life. And Tony Soprano is family life in the gangster world. Everybody Loves Raymond is set in the same place, Long Island. Mostly writers don’t write realistic novels about family life anymore.

GG: I find it very interesting that you mentioned that you consider one of your favorite books, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, one of your great books. And Walter Benjamin argued that storytelling was a vanishing practice.

LM: Right. Storytelling in the classic sense is pretty well gone, I think.

GG: It’s fascinating to me that what you consider one of your greatest books was written here at the Dairy Queen.

LM: I argued in the book that Dairy Queens sort of became community centers in these little Texas towns.

You know we’re all crushed here [in Archer City] because we’ve had a social catastrophe. The restaurant right across the street from The Spur hotel closed and we’ve had all sorts of gossip about it. Now that it’s closed people have no place to go for breakfast. The Dairy Queen used to be a good place to go for breakfast, because they opened for the oil field workers at five-thirty in the morning. This little cafe did the same thing. The Dairy Queen now opens at about eleven or so. I think that’s because they can’t get the kids to pass the drug tests.

BM: How much do you worry about the fate of Archer City? Is it going to be a ruin on the prairie in fifty years?

LM: Archer City floats on a sea of oil. It’s been an oil town since 1905 when the first gusher hit. It’s been an oil town all through the thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties, and it has always been a very, very rich land. Eighty-eight million barrels a day comes out of the ground.

The mythology of the cowboy has overshadowed oil because it’s so much more poetic. More poetic to see men on horses galloping around roping cattle or something. People in dozer caps don’t really get much respect, but they’ve been the ones who’ve run the county as long as I’ve been here.

GG: Over the years, I know bookselling, book dealing, the book business has been every bit as important to you as your writing. Do you see your bookstores and the book business, the work you devoted so much of your life and attention to, becoming an important part of your legacy?

Larry: I don’t think it will. My son and his talent, and my grandson and his talent—they’re in music. My grandson is faintly curious about the book—he’s not a book man—and James is even less a book man, although James reads a whole lot more than he wants people to think. He’s a very well-read young man.

The book gene, the rare book gene, the book trade gene is a rare gene. Not many people have it. Not many people have it as intensely as I’ve had it. And I think I’d be crazy to think that somebody’s going to pick it up and do what I’ve done. It’s not going to happen.

OK, folks, I’ve got to go to my next job.