A few months ago, my son, Sam, was home in Houston for a very abbreviated spring break, and we were out having lunch in between his incoming and outgoing text messages. Suddenly he looked at his phone and blanched. Before I had a chance to ask what was wrong, he typed a response, a new message beeped, and he clutched his heart and fell back in his chair with relief. Beaming, he turned his phone toward me. I squinted at a photo of something that looked like a wedding announcement, on cream-colored paper with fancy italics. “I’m done!” Sam prompted when I took too long to understand.

It was the invitation to his college graduation. When one of his roommates had texted to say that three invitations had come to their apartment, Sam, whose college experience has sometimes resembled an HBO end-of-season cliffhanger, had demanded proof that his name was actually on one of them.

And there it was. As I studied the invite, something warm and wet pressed at the back of my eyes, and my throat closed. The mortarboard and the diploma would come soon enough, as we became live figures in one of those Kodak moments that never seem quite real for being so universal. But I knew just then, amid bites of our not-so-fancy La Madeleine salades, that another chapter of our lives had come to an end.

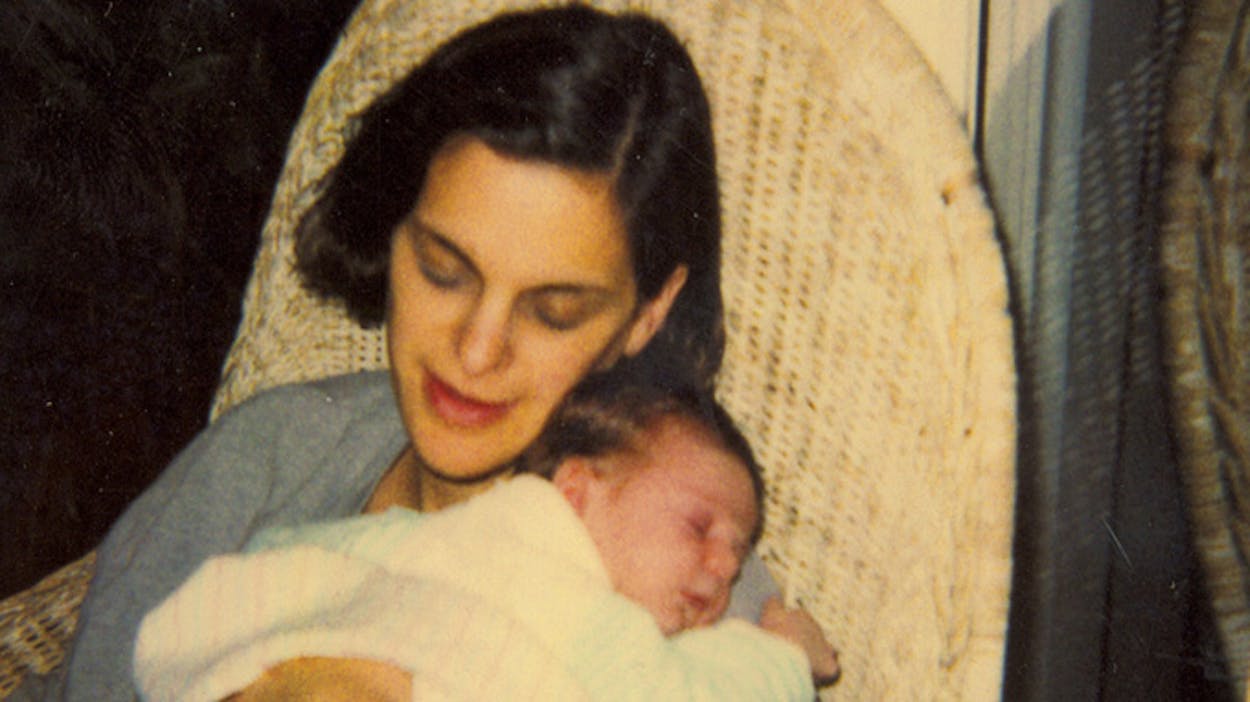

When Sam, who is my only child, went away to college in New York, in 2009, I adapted fairly quickly to the rhythm of his comings and goings: the anticipation of his arrival (Clear the calendar! Stock the fridge!); the heady rush to the airport to pick him up; the luxurious days that stretched ahead of my husband, John, and me once we had our son back again; then slowly, insidiously, the advance mourning that preceded his inevitable departure; and finally the bleak return trip to the airport, followed by the few months’ wait before the cycle started again. Spring break, summer break, Thanksgiving break, Christmas break—in years past, when Sam was still living at home, we’d given in to this enforced downtime with a mixture of angst (“These kids are never in school—how am I supposed to get any work done?”) and gratitude (one of my most treasured photos remains a shot of Sam at fifteen asleep on a train during a family trip to Scotland). But once Sam went away to college, our time together always seemed to have a clock ticking in the background, a reminder of the day when our schedules would no longer mesh so easily, if at all.

By his second year at college, all the back and forth between Houston and New York had begun to remind me of the long-distance love affairs I’d had during school and for years after—his visits had the same roller-coaster feel, the same hits of pure joy and nearly inconsolable sorrow. But in my twenties, I’d had the luxury of creating my own agony, ginning up drama pretty much for the hell of it. The substance of my life was, after all, pretty insubstantial. Now that I’m older, my interest in generating excess anguish has gone the way of cravings for fragile foreign cars and four-inch platforms. Having experienced real pain—the loss of a parent, the serious illnesses of friends, the occasional failures of the body that portend more to come—I’ve learned not to borrow trouble. Still, what I can’t ignore about this stage of my life as a parent is that letting go does not get easier. It gets harder.

Like so much of life, this realization, as clichéd as they come, caught me by surprise. Months before Sam left for college, I read up on empty-nest syndrome in the same way I had studied pregnancy nearly two decades before, with close to the same outcome, which was terror. But this time, instead of receiving warnings about placenta previa and postpartum depression in What to Expect When You’re Expecting, I was cautioned about extreme grief from websites that intoned, “Parents may find themselves spending hours in their children’s rooms instead of engaging in normal, everyday activities…. It may seem that there’s nothing left to do in life and they’ve served their purpose.” What to do? Some sites suggested creating a “letting-go ritual.” A despondent parent might “sail a lantern with a candle in it down a stream,” “plant a tree,” or “bronze something special of your child’s.”

That’s not what I experienced, though—at least initially. For almost twenty years I had been shaving an hour here to gain an hour there to be a room mother or Halloween carnival assistant or homework helper or carpool driver or just to serve a facsimile of dinner before bath and bedtime. I don’t regret a minute of it—all those mundane activities made for a day-to-day closeness that helped Sam and me negotiate the horror of adolescence and the hell that was the college application process. But this also meant that my time was never entirely my own. A few weeks into Sam’s first semester away, I dropped in on a friend in the middle of the afternoon. It was a crystalline day with just a hint of fall in the air; she’d opened all her windows to let in what was probably the first cool breeze of the season. We drank coffee, gossiped, and sprawled on the sofa like teenage girls while the shadows lengthened and the sky yellowed, then faded to a deep, velvety blue. I had no place to be, nothing to do. In the space of that afternoon, I felt something that had been wound very tight give way, and there I was, the person I used to be. “Welcome back,” I thought. “Welcome back.”

Since then, I’ve lived one life when Sam is home and another when he isn’t. When he’s in New York, I probably work too much and exercise with a passion matched only by its futility. Sam is never far from my mind, but the daily (attempted) management of his business isn’t my job anymore. Instead, John and I see a lot of friends, who, like us, no longer have to rush home to liberate the babysitter. We travel. We sleep in. We got two puppies, a common mistake for my age cohort. When I miss Sam, I call him and tell him so, though he probably doesn’t know that because, like everyone else his age, he never listens to voicemail. (“What’s up?” he asks blithely when he calls me back, unconcerned that I’ve already left him a minutes-long rundown.) Somehow, I’ve had it in my mind that our life as a family would always be this way, or that it would go back to being the way it was before Sam’s departure for college. I hadn’t thought about what would come later, after graduation.

Now I think about our more permanent separation whenever, for instance, John and I visit and take Sam and one of his newer love interests to dinner. Staring across the table at a relative stranger on those longish, awkward, excessively polite evenings—So, where are you from? What do your parents do? What’s your major? Oh, social media psychology? How nice!—I can’t avoid looking ahead to when our tiny family becomes a foursome instead of a threesome. Which habits of this newcomer will not wear well? Which beloved holiday will be spent with the in-laws instead of us? What’s the gene pool behind that winning smile, and how’s it going to play out? Somewhere between the appetizers and the cappuccinos, I’ve already made the transition into an alternate mother-in-law universe I may never actually inhabit.

At such times I’m reminded of one of my mother’s less impressive moments, when, two days before my wedding, with my husband-to-be’s entire family already assembled from out of town, she asked if I could go out to dinner with her and my father, “just the three of us.” At the time, her suggestion seemed unforgivably rude. But in retrospect, I understand her impulse. She just wanted one last moment, alone, with her daughter, but by then it was too late. I had far more than one foot out the door.

And Sam does too. “How often did you share your problems with your parents once you were on your own?” a friend asked me on a day I’d felt something wasn’t right in Manhattan but couldn’t extract the truth from two thousand miles away. “Not very often” was the obvious answer and the one I gave, but I’d had a good excuse. My mother was a loving yet anxious woman, and I knew that any sharing of intimacies would be followed with incessant questions about how “it” was going and how I was “feeling,” which, in the complex patois of mothers and daughters, I’d heard as “When are you going to solve that problem so I can stop worrying about it?”

Like every parent, I tried to do better with my own child, sure that my efforts would keep him closer and our relationship smoother. I try not to pry, or at least I preface my prying with the phrase “You don’t have to answer this, but…” I couldn’t snoop even if I wanted to these days, though any parent who has taken the occasional illicit peek at a text string knows that that’s just an invitation for more worry. Making peace with not knowing what my son is up to every minute is a discipline that requires undoing years of vigilance. It would be easier, as my mother knew, to get regular root canals.

Instead I’m coming to terms (again) with the fact that I cannot escape predictable crises of adult life any more than the next person. I’ve now entered that period when I’m rewarded for all my hard work by watching my son move—gracefully, confidently—into his own life, the one he won’t be sharing with us. He’s got good friends in Manhattan who, like him, will be staying in the city after graduation; he’s got his local hangouts; he’s got work waiting for him when he gets his diploma. Without consulting us, Sam has picked a neighborhood to live in, a relatively cheap one that, naturally, isn’t gentrifying fast enough for my taste. All of this means that John and I more or less aced our parenting finals, but it’s news I appreciate more than I enjoy. It’s the difference between taking an exotic, arduous journey and finishing one: now I’m back home with my photos and souvenirs and have to figure out what comes next. Meanwhile, the road still ahead of me isn’t quite as sunny or as long as I used to think it was.

The last time Sam was home, I could see that he was at looser ends than usual. He slept in, lunched late, met old friends at bars after dining with his parents. (I got props but also felt like an enabler when I recommended a hip spot on the Westheimer strip.) He’d roll in around one or two in the morning, then spend a few more hours digesting past seasons of Breaking Bad in the family room. He was happy enough, but he was biding his time, this handsome, deep-voiced son of mine, waiting for the day he’d catch the plane back to his real life.

“How’s my grandson?” my father asks whenever we talk, which is nearly every day now. He’s 85 and frail and lives in San Antonio, in the apartment he shared with my mother until she died, three years ago. It’s easy to tell how much pleasure a phone call or even the shortest visit gives him. I’d say that no one on earth ever sounds quite as happy to hear from me as he does. We don’t talk about much of import—I give him girlfriend advice that he ignores, or suggest that he might cut back on his corgi’s rations, since she’s getting chunky. He ignores that too. When I go for a visit, we read the paper in the morning, idly complaining about various politicians; we dine at noisy restaurants where he pretends to hear what I say. He loves tales about Sam’s adventures in New York, maybe because he was young there once himself. But he especially likes those stories in which I am mildly exasperated about something Sam has done—a free limo ride from a stranger he and three girlfriends accepted in the middle of the night comes to mind. My father listens, and laughs and laughs, always until it hurts.