Before he begins the hours-long process of replacing the blood in a body with embalming fluid, James Bryant takes a moment to speak with the decedent on the table in front of him. If it’s a woman, he tells her how beautiful she is and how proud her family will be when she’s all made up. If the person has arteriosclerosis, making it difficult to get the embalming needle into the carotid, he takes a sterner tone. “If they’re giving me a hard time, I let them know. ‘You might as well cut it out, because you’re not going to win this fight,’ ” he says with a grin.

Three years ago, when Bryant gave a continuing-education seminar to a group of embalmers, he asked if anyone else ever talked to the bodies. He was surprised at the show of hands—relieved, even. “Because that was going to be part of my seminar: ‘Talk to the bodies. Bring the very best out in them.’ ”

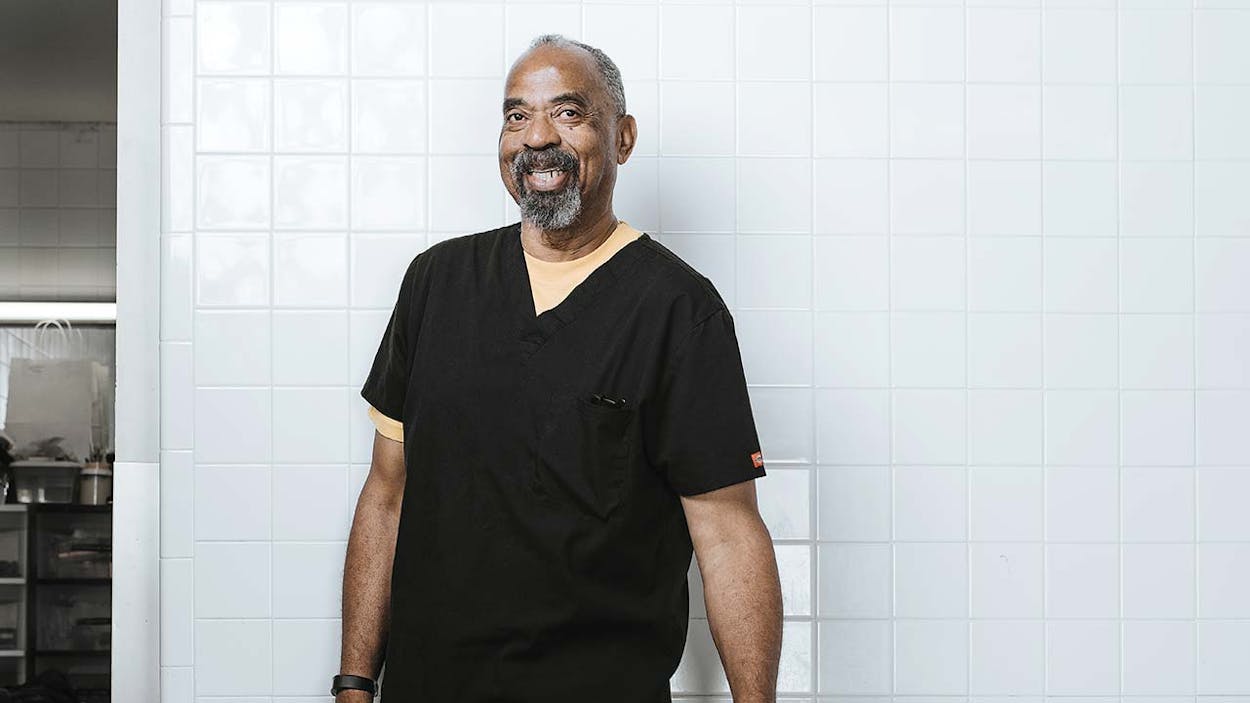

The San Antonio native’s talent for bringing out the best in his decedents, along with his service to the embalming profession, was recognized in March when he was named the National Embalmer of the Year at the Annual Osiris, or convention, of Epsilon Nu Delta, a professional fraternity for embalmers. The organization was founded in 1942 as a predominantly black study group at a Chicago embalming school and today has about six hundred members.

“The greatest thing that has happened to me in the funeral profession is that banquet,” he says. “So many embalmers have given a lot and never received such an award, and it made me feel very special.”

The 66-year-old has been drawn to caring for the dead virtually his whole life. At age 5 he started “playing funeral home,” inspired by a cousin and a fellow churchgoer who were in the funeral business. On Saturdays he would complete his chores, put on his bow tie, and hold funerals for dead birds and butterflies, using his tricycle and attached wagon as a hearse. “When other kids went to the park to play, I had funerals in my backyard,” he remembers. “I was the undertaker, the preacher, the grave digger—everybody.”

He learned how to embalm during his senior year at Phillis Wheatley High School, when a work program gave him the chance to spend most of every school day at a funeral home. After graduation he was drafted and served a year in Vietnam before returning to Texas, earning his mortuary science degree and starting work in 1972 at Lewis Funeral Home, which serves a largely black clientele on San Antonio’s East Side.

In the 44 years he’s worked in the small, white-walled prep room, Bryant has embalmed thousands of bodies. He’s seen those bodies get larger as obesity has become more common in America; his largest decedent weighed 881 pounds, enough to require an oversized casket and necessitate the purchase of a second burial plot. Four-hundred-pound bodies aren’t unusual.

Funeral customs have shifted over time. Until a few decades ago, black funerals were lavish and lengthy affairs, often beginning with a wake at the decedent’s family home and stretching for several days. But the generation arranging funerals today moves at a different pace, Bryant says. “They don’t have time to mourn and grieve and sit around the house with Mom or Daddy or brother or sister in there. They’re a fast-moving generation, and they want to do everything right here and go back home.”

Bryant is licensed as both a funeral director and an embalmer, but he prefers the latter work. Even when he’s finished his embalming for the day, he stays in the prep room, sitting at a small desk a few feet from the tables of sheet-draped bodies. He listens to jazz on satellite radio, studies his Bible, prepares the sermons he occasionally gives as a membership minister at his church. From time to time he gets up to check on his quiet company and touch a hand or two.

Bryant has seen many familiar faces on the embalming table. He embalmed his mother, honoring one of her more difficult requests. “She didn’t want anybody else but me to do it. So my mother can say at least I minded her one time,” he says. He’s embalmed his father, brother, aunts, uncles, nephews, and classmates from grade school. When one heavy-drinking friend turned up at the funeral home, Bryant tsk-tsked at the body. “I told him, ‘Man, I tried to tell you this was going to catch up with you.’ ”

Bryant is a trim man who wears a Fitbit and works out at Life Time Fitness three or four times a week. It’s one way he copes with the challenges of the job: embalming a child, or someone who’s committed suicide. Once, he worked on a man who’d been shot 54 times. “Dealing with death every day is not for everybody,” he says. “It can be overwhelming.” He takes time off to visit Spain or Morocco with a group of funeral directors (his wife of 33 years is not keen on traveling; his four adult children are out of the house), but he always misses his work.

“I was born to be an embalmer,” Bryant says. “I’ve never been afraid of this. I never struggled with it in school. I picked it up”—he snaps his fingers—“like that. I don’t know what it’s like to have a job; I just get up every day and do something I love to do.”