Before he moved back to Texas and raised $5.7 million on Kickstarter, Rob Thomas was a very successful failure. After a brief, acclaimed career as a young-adult author, he discovered he had a gift for writing smart TV shows that were intensely loved by small, commercially insignificant groups of people. The first, a 1998 romantic comedy called Cupid, lasted just fifteen episodes on ABC. Still, Twentieth Century Fox liked it enough to give Thomas, then 33, a four-year production deal worth $8 million. He bought a tricked-out house in the Hollywood Hills with a pool and an outdoor kitchen, and he could afford to fly his friends in the Austin-based Neil Diamond tribute band the Diamond Smugglers out to play his annual Halloween party. Once, the security guards for his next-door neighbor, Britney Spears, popped in for a Shiner Bock. But the Fox deal was a bust: not one of the ten pilots Thomas wrote in those four years got on the air. “It was like writing into a trash basket,” he says.

A free agent in 2003, Thomas dusted off a script based on a proposal for a book he’d never written called “Untitled Teen Detective Project.” Originally conceived with a male protagonist, the idea became the UPN series Veronica Mars, starring Kristen Bell as the teenage daughter of a private eye. High school noir from the same family tree as Nancy Drew, The Outsiders, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the show was set in the fictional, corrupt beach town of Neptune, California. It pitted everyday teen melodrama against the adult menace of violence, greed, and infidelity, as well as race and class divides. Small, cute, blond, and acid-tongued, Veronica dealt with dark, disturbing situations—the first season turns on both the murder of her best friend and the sexual assault of Veronica herself, after being slipped GHB at a party.

The show premiered in September 2004, and a certain segment of TV viewers absolutely loved it. “Best. Show. Ever,” wrote Joss Whedon, the creator of Buffy. “I’ve never gotten more wrapped up in a show I wasn’t making. . . . These guys know what they’re doing on a level that intimidates me. It’s the Harry Potter of shows.” Critics also liked the show. Joy Press, of the Village Voice, called it “a fusion of Chinatown and Heathers,” while blogger Alan Sepinwall eventually named it one of the best dramas of the 2000’s, right up there with The Wire, The Sopranos, and Friday Night Lights.

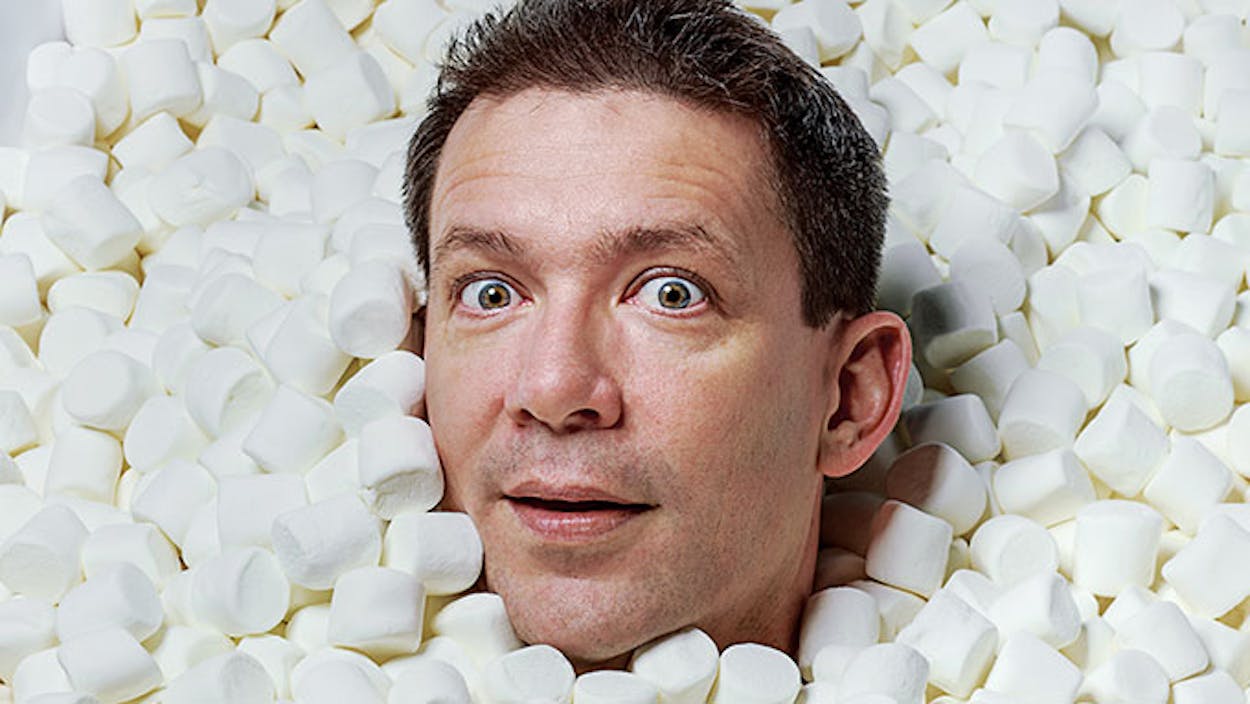

But like Friday Night Lights, as well as Freaks and Geeks and Whedon’s own Firefly, Veronica Mars struggled to capture viewers beyond its obsessive core audience. During the three seasons it aired, the show generally drew between 2.5 and 3 million people. This put it among the ten least-seen prime-time network shows, and before the fourth season, it was canceled, much to the despair of its fans (they’re known as Marshmallows, a pun based on a famous line in the first episode).

Measured against recent cable hits like AMC’s Breaking Bad, which didn’t top 2.5 million viewers until its fourth season, or Mad Men, which drew just 2.7 million for its most recent season finale, Veronica Mars was practically a smash. But the TV business was a different place seven years ago. In the time since, streaming video, DVDs, and downloads (both legal and illegal) have given high-quality cult shows numerous ways to reach a larger audience and encouraged execs to put a greater premium on patience. The resulting boom is often called the “new golden age of television.” Ten million people watched Breaking Bad’s series finale this past fall. The beloved-but-canceled Fox sitcom Arrested Development was eventually brought back by Netflix. AMC’s crime show The Killing has been canceled and then reanimated twice.

Seeing all of this, both the creators and the fans of Veronica Mars held out hope that their show might also make a comeback. Thomas and Bell say that in the years after the show was canceled, the possibility of a Veronica Mars movie came up in every interview they did. But initially, Warner Bros., which owns the show, was not keen on the idea, and Thomas moved on. He co-created Party Down, an oddball sitcom that shared DNA and actors with The Office, Parks and Recreation, and Children’s Hospital. Again, critics and a few diehards loved the show. The American Film Institute named it one of the ten best shows of 2009. It made Entertainment Weekly’s “25 Best Cult Shows of the Past 25 Years.” Details did an oral history of it. But because it aired on the premium movie channel Starz, a sizable audience was extra hard to come by. The show’s season-two finale, in 2010, had—this is not a typo—74,000 viewers.

“My shows tend to be just off-center enough to turn off ‘the masses,’ ” Thomas says. “I can get very depressed about it. Why did Veronica Mars go three years and One Tree Hill and Supernatural go for thirty-nine? I don’t know.”

It is, to some extent, the nature of the TV game. Each season, a typical network might hear five hundred pitches and order seventy pilot scripts. “Of those seventy scripts, they might make twelve or fifteen pilots,” Thomas estimates. “Of those twelve or fifteen pilots, maybe five get on the air, and maybe two of those survive to season two. The good news is, once you get a script ordered, you’re getting paid, and TV writers are paid pretty well. But you’re a long way from getting a show on the air.”

Which is one reason why, in 2009, Thomas and his wife, Katie, moved back to Austin. They didn’t want their kids—Greta, who’s now eight, and Hank, who’s five—to grow up in Los Angeles. Just as important, the lowered cost of living would mean less pressure to take jobs Thomas didn’t want. “Having the ability to pursue passion projects was a big motivator,” he says. But getting those projects off the ground remained as tough as ever. Party Down got canceled, and Starz also bailed on a show Thomas was working on about an indie-rock band, based on his own days in the Austin music scene. Fox had him shoot a pilot about feuding Little League parents but didn’t pick it up.

Veronica Mars stayed on the back burner. Warner Bros. didn’t want to make a movie, but it also wouldn’t allow Thomas to make one independently. It probably didn’t help that Serenity, a $40 million film adaptation of Whedon’s Firefly, lost money at the box office. “My Veronica Mars movie hope-meter had gone on a roller-coaster ride over the years,” says Thomas. “But I was in a pretty deep trough. Kristen always says she knew it would happen some day. I can’t say I felt the same. I never gave up hope, but I came very close to it.”

Thomas has always considered Austin home, ever since his family moved from central Washington to Texas on his tenth birthday. His father, Bob, had a job as vice principal at Westlake High; his mother, Diana, taught in Dripping Springs. They also started a business through Bob’s brother Doug, who did the books for Rooster Andrews Sporting Goods and Schlotzsky’s. They took over the latter company’s San Marcos franchise, eventually owning five locations of the sandwich shop.

Austin was the big city compared with rural Washington, and Thomas had a few awkward junior high moments he still draws on for his work today. “I can remember so clearly doing a square-dance unit in P.E.,” he says, “and a boyfriend and girlfriend squabbling in front of me and the boyfriend saying, ‘Oh, you don’t like it? Well, you can dance with that guy,’ and pointing at me. It was straight out of a John Hughes movie.” But after moving to San Marcos in the seventh grade, he found his footing as a jock, though he also wrote for the school paper.

His first love was basketball; during his senior year Thomas was All–Central Texas on a 33-4 San Marcos High School team that was ranked fourth in the state. But as a six-foot-two low-post player, he was not college hoops material, except at places like Our Lady of the Lake and Texas Lutheran. He almost went to Texas Tech on a partial journalism scholarship but instead opted for football at TCU, walking on for the late Jim Wacker, who’d just left Southwest Texas State, in San Marcos. A second-string tight end and special-teamer, Thomas had his first and only Horned Frogs highlight in a game against Kansas State during his sophomore year. He intercepted a pass off a fake punt, a moment immortalized by Wacker on his television show: “Rob Thomas . . . great interception . . . jumping up and down, acting like a clown!”

Thomas was on scholarship heading into his junior year, but he had already fallen in with the guys who would end up in the Austin bands the Wannabes and the Diamond Smugglers. “I was spending all my free time in Deep Ellum new-wave and punk clubs rather than with my football teammates,” he says. “I was proud that I’d survived football, but I was playing behind another guy with the same amount of eligibility as me, and I knew that he loved it more than I did.” So Thomas quit football, spent one more semester at TCU editing the student magazine, and then transferred to the University of Texas.

He started cutting his hair funny and formed a band, Public Bulletin, with some old friends from San Marcos. It eventually evolved into Hey Zeus, melodic guitar rockers on the fringes of Austin’s “New Sincerity” music scene. They were ambitious, taking out a bank loan to help buy a van and booking East Coast tours. “We actually had too much ambition for the amount of talent we had,” Thomas says. “That has always been my weird talent, having ambition.”

After college, Thomas taught journalism and English at San Antonio’s John Marshall High School and was an adviser for the University of Texas student magazine UTmost. From 1991 to 1993 he was the journalism adviser at Austin’s Reagan High, where his broadcast class was serious enough for his students to win national awards. They were almost surely the only high schoolers to cover the Branch Davidian standoff. “ ‘I’m not telling you to cut school,’ ” one of his former students, Viet Nguyen, remembers Thomas saying before he and some classmates headed up to Waco with press badges, a VHS camera, and a tripod. They talked their way past the sheriffs and ended up borrowing some lights from CNN.

Thomas would later hire Nguyen to work on Veronica Mars. It was payback, in a way, as Nguyen and his classmates had nominated Thomas for teacher of the year in a competition sponsored by the educational broadcasting company Channel One. Thomas didn’t win, but Channel One offered him a job in L.A., which he took, leaving Texas in 1993. It was during his Channel One job that he began writing fiction, and it was there that he got to know the niece of then–CBS president Jeff Sagansky, to whom he eventually sent an advance manuscript of his first book, Rats Saw God. It was such a long shot that when Sagansky called him up to say he loved the book and wanted to see some film or TV scripts, Thomas didn’t even have any.

The final minutes of the Veronica Mars season-one finale is a dream sequence in which Veronica talks to her dead friend, Lilly Kane, while a fragile, psychedelic, Beatles-sounding ballad picks up volume in the background. The song is “Lily Dreams On,” by Cotton Mather, one of many Austin bands to be featured on Veronica Mars. While the character was not named after the song, Cotton Mather would make an even bigger contribution to the show: the band introduced Thomas to Kickstarter. In 2011 front man Robert Harrison used the website, which connects individual donors to a wide variety of projects in search of financial support, to raise more than $17,000 from 301 fans for a deluxe reissue of the group’s 1997 album, Kontiki. Thomas gave $100.

After that, the idea that he could crowd-fund the Veronica movie slowly began to take root in Thomas’s mind. Very slowly. “Once the thought of financing the movie on Kickstarter entered my head,” he says, “I immediately dismissed it as dumb.” Crowd-funding something as large as a feature-film budget was basically unprecedented. Thomas figured he’d need millions, and on Kickstarter there were only a few successful short-film and video projects, all in the $400,000 range. Thomas also figured, correctly, that Warner Bros. would still say no, because for any company in Hollywood, that’s always the easiest answer, especially when the question involves something new and risky.

“I remember him starting to talk about it,” says Dan Etheridge, one of Thomas’s producing partners. “It sounded crazy.” But it also sounded, well, like Thomas, the same guy who came up with the idea to self-finance the Party Down pilot and shoot at his house. DIY is what he’s always known, whether playing rock and roll, encouraging his students to hustle up to Waco, or writing fiction every day at five in the morning before heading off to his day job. Nguyen remembers going with Thomas to see Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi in 1992, before it was released outside Austin, and discussing how Rodriguez made the shoestring film. “ ‘That’s so crazy,’ ” Nguyen recalls telling his former teacher. “ ‘He spent all his money, seven thousand dollars, to make a movie. That’s like selling your car. Would you sell your car to make a movie?’ And Rob’s like, ‘Yeah, I would.’ And I was like, ‘Oh.’ ”

Things began to fall into place when Thomas found an Internet-savvy patron: Thomas Gewecke, who was then the head of Warner Bros. Digital Distribution and is now the parent studio’s chief digital officer and executive vice president of strategy and business development. Gewecke understood instinctively that what Thomas was really pitching was a new kind of viral marketing: It wasn’t just about getting Warner Bros. a free movie. It was about mobilizing a community of fans.

The hands-on involvement of Bell was also crucial. When Thomas pointed out what a big commitment it would be for her and some of the other actors to sign three thousand posters (a prize, along with several other goodies, for backers who contributed $200), Bell said, “We’ll have a party at my house, we’ll get a bunch of beer, and we’ll just sign posters all day. It’ll be great!” Everyone pitched in. Bell’s boyfriend (now husband), the actor Dax Shepard, built a puppet theater for Thomas to use in the fund-raising video, which portrays several members of the Veronica cast hanging out while Thomas entertains them.

The fund-raising goal was a minimum of $2 million in thirty days (if a Kickstarter doesn’t meet its goal, none of the contributors get charged), but Thomas knew he wanted a lot more than that: $5 million was always the real target. The afternoon before the campaign launched, Thomas and Bell tried to tease the news on Twitter but got only five replies (albeit with several hundred favorites and retweets), even though the actress had more than a million followers (Thomas had around five thousand, half of whom, he figures, thought @RobThomas was the guy from the band Matchbox 20).

Suddenly, Thomas says, “there was this little bit of doubt in my mind—‘What if the people who’ve been telling us to make the movie have been, like, the same twenty people?’ ” Until the very second that the Kickstarter went live, he half-expected Warner Bros. to come to its senses and call off the project. “It was like the opposite of an execution,” he recalls. “You’re praying you get to go through with it, that the phone doesn’t ring.”

On the morning of March 13, 2013, Thomas hit the “Launch Project” button on his laptop screen. He’d also installed the Kickstarter app on his iPhone, with the notifications option turned on. For the next several hours, his phone vibrated continuously, never pausing long enough for him to change the settings on the app—a new backer was joining the project literally every second. About an hour in, Thomas realized what was happening. “I finally felt absolutely like we were going to get to make the movie,” he says. “That’s when I got hit by just a tidal wave of endorphins or adrenaline. I felt woozy.”

They raised $1 million in four hours. By the end of the first day, they had $2.5 million and had set several Kickstarter records, becoming the fastest project to reach $1 million and the fastest project to reach $2 million (eleven hours). In the end, they raised $5,702,153, making Veronica Mars the third-largest Kickstarter ever and the highest-funded film or video project (the previous record was $808,341, for a web TV series). With the last-minute addition of a $1 donation category, they also set a new record for the most total backers for any project: 91,585.

A huge momentum-builder—a kickstarter for the Kickstarter, if you will—came in the first hour, when Steven Dengler, the CEO and co-founder of XE.com, a currency conversion site, donated $10,000. In return, he got a small speaking role. The donation made him the project’s single biggest backer, but Dengler isn’t a huge Veronica Mars fan. He’s just a self-described geek who loves crowd-funding and understood that Thomas was doing something big.

“This was the moment Kickstarter crossed over from being kind of obscure and nerdy and something maybe only nerds knew about to something that was more mainstream that everyone knew about,” says Dengler. “This is a social movement, it’s not a technology. It’s a concept, the concept that people don’t need to go to the gatekeepers. You don’t have to rely on studios, you don’t have to rely on people like me, a patron—I mean, if you get one, that’s great, but you don’t need any one person or organization. You can go straight to the fans to get something made. Honestly, I don’t think people will fully appreciate how significant a change this is culturally for a generation.”

“It made me feel like I can really make a difference,” Stacey Aversing, a $50 backer from Louisiana, told me in April, after she’d driven seven hours to Austin’s Dog and Duck Pub to join Thomas and five hundred other Marshmallows in commemorating the last hours of fund-raising. Another person I met that day was Sarah Garvey, a 23-year-old artist who said her own high school experience at Plano West had felt similar to Veronica’s. “I went to a wealthy high school like Veronica, and I showed up in my beater car. It was embarrassing, but you learned to be yourself through that kind of stuff. So it was nice to have a show at the time I was in high school with a character that I felt was more like me.” She gave $150, which earned her a reserved seat at a special fan event during San Diego’s Comic-Con festival, in July.

A Kickstarter is not without expenses. Factoring in the cost of physical goods (T-shirts, stickers, posters), shipping, and event logistics, Thomas estimates that it cost $2 million to raise $5.7 million, but Warner Bros. ended up covering the expenses, which let Thomas spend almost all of that $5.7 million on the film. Still, as he had suspected, the publicity turned out to be even bigger than the funding. “Veronica Mars is in the public consciousness now in a way that it never was when it was on the air,” he says. “You know when you meet people in the airport or whatever and they ask you what you do? It used to be that one in fifty people would know what [Veronica Mars] is, and I feel like now it’s one in three people.” Plus, he’s no longer automatically mistaken for the guy in Matchbox 20. One night during the movie shoot, he went to grab some takeout at an L.A. restaurant. When he gave the counter guy his name, the guy looked up and said, “The singer or the director?” It was the first time that had ever happened.

Thomas finished the Veronica Mars script three days after the Kickstarter ended. On March 14, exactly one year and one day after the crowd-funding campaign began, the movie will hit theaters (the world premiere is at South by Southwest, in Austin, on March 8). More than 60,000 backers who gave $35 or more will receive a digital download within a few days of the movie’s theatrical debut, a promise made when Thomas figured that the film would be released in only a few cities. Instead, it’s opening on 260 screens, small by blockbuster standards but huge for a low-budget film.

And a low-budget film it is. Though the $5.7 million allowed Thomas to do things that he never could have done with $2 million—shoot in L.A., stage a car crash, bring back a higher number of favorite old characters—the movie was still made on a shoestring. Everybody, including Bell and Thomas, worked for scale, making a fraction of their normal rate. Thomas spent most of the production crashing in the guest room of his childhood friend Daron Norris (who plays Neptune public defender Cliff McCormack). And the entire film was shot in 23 days, a breakneck schedule that generally allowed for just a few takes per scene. Luckily, because most of the actors had played their roles before, they didn’t need more than that. (There are also some actors who were never on the show, among them Jerry O’Connell, Jamie Lee Curtis, Gaby Hoffmann, Party Down’s Martin Starr, and James Franco.)

Last June I visited the set to see the first crowd-funded movie close up. In the new story line, Veronica has just become a lawyer in New York when her greatest love and frenemy, troubled rich kid Logan Echolls, is accused of murder, bringing her back to Neptune against all good judgment. The day I arrived they were shooting Neptune High School’s tenth reunion at the Edison, a cavernous steam-punk club in downtown L.A.. The room was dark, extremely hot, and packed with actors, extras, and crew. Thomas, who turned 48 in August, greeted me by apologizing for the fact that he was wearing a V-neck undershirt. “I did come with a shirt on,” he said.

They had two days at the Edison to capture three days’ worth of scenes, but the mood was more buoyant than stressed. The Neptune reunion was also quite literally a Veronica Mars reunion, with many of the actors seeing one another for the first time in years. Several dozen particularly passionate (and well-heeled) Kickstarter backers were there too, some of the fans who had donated between $2,500 and $3,500 for the chance to be an extra in the movie and to have lunch with the cast.

“They were so much fun,” Thomas says. “It was electric. Even when I watch in editing, it’s so funny, because I can pick out our Kickstarter backers. They’re so alive in these scenes, and most of them are overacting, which I find very charming. None of them are spoiling scenes, but they’re always the biggest ones.”

In many ways, the Kickstarter was also part of the creative process. There are scenes in the film that really have no reason to exist except to give a cameo to an old character. Even the reunion’s major set piece, a fight scene, was a costly, time-consuming bit of action that Thomas wasn’t sure he needed. But since he’d talked up the fight scene during the last weeks of the Kickstarter as an example of something they could afford to pull off if they hit $5 million, he felt obligated to include it.

It’s a heady thing, to have such a direct line to the expectations of your fans, but Thomas doesn’t seem to mind. He’s an obsessive fan himself. After he’d proposed to Katie on a cruise ship, in 2004, they’d watched all eighteen episodes of Freaks and Geeks during the remainder of the trip. “I totally geek out about shows,” he says. “I mean, I write [Breaking Bad creator] Vince Gilligan fan mail every year. I do love television so much, when it’s done well.”

Thomas has half-joked that he’d love to see Veronica become a “Bond franchise.” And if the first movie is a success, he certainly won’t have to fight as hard to get another made. “Next time maybe the studio will just give us the money,” he says. Still, a sequel would probably have to begin with another Kickstarter, if only for a token sum, to continue the emotional investment and sense of collaboration. The Marshmallows wouldn’t have it any other way.