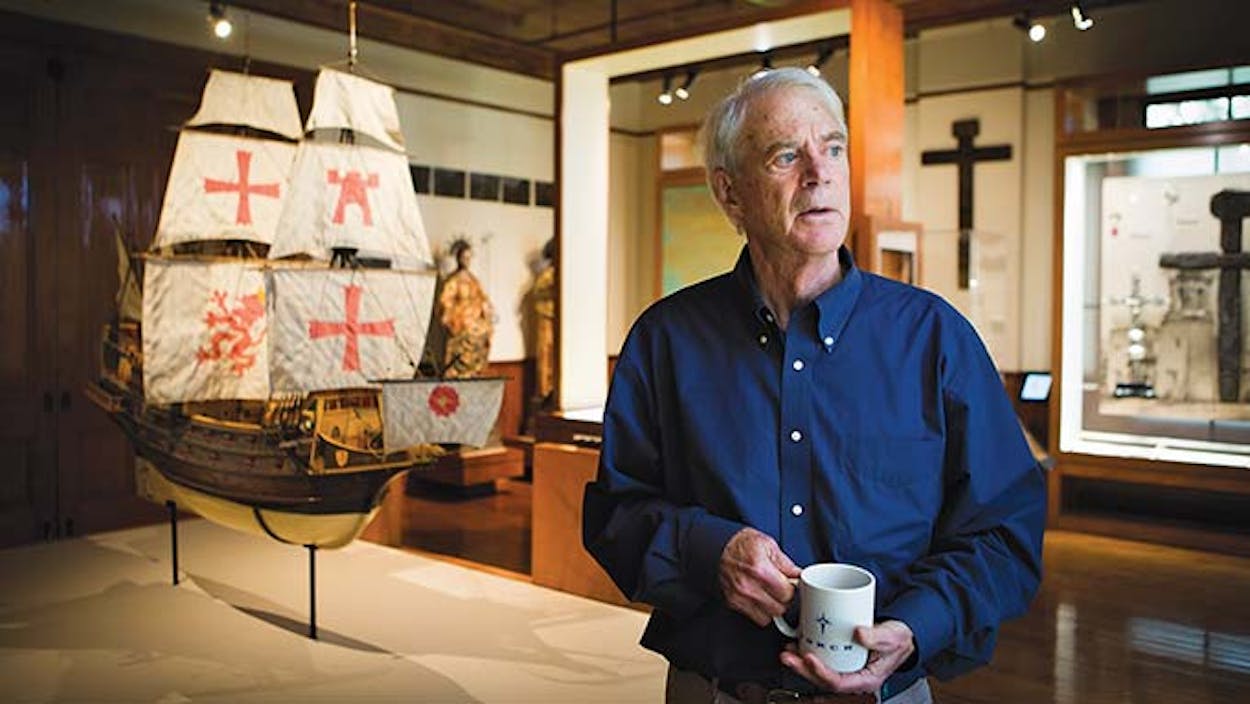

James Perry Bryan Jr., a trim man with neatly parted silver hair and courtly manners, sits at the head of a long mahogany conference table, ignoring the cup of coffee his assistant has brought out to him on a saucer. He wears a dark-blue blazer, creased khakis, and loafers—patrician chic. When he speaks, his voice has a quiet, gravelly authority.

“We have the greatest history of any state in the union—there’s nothing to compare to it,” he states flatly. “That’s not Texas brag. More books have been written about it than any state in the union. In fact, there are more books about Texas than all the rest of the states combined. And it’s not because we have so many history professors in Texas. It’s that we have such a diverse and colorful history.”

It’s a history in which Bryan’s family has played a leading part. His great-great-great-grandfather was James Bryan, the friend, business partner, and brother-in-law of Stephen F. Austin. The city of Bryan is named after his great-great-grandfather, a banker and land developer; his great-great-uncle was the secretary of the Republic of Texas’s legation to the United States. His father, the late James Perry Bryan Sr., a former University of Texas regent and president of the Texas State Historical Association, amassed a distinguished collection of Texana.

Growing up near Freeport in a house stuffed with historical relics, Bryan looked forward to the day he would inherit the family collection. Then disaster struck. After a land development scheme collapsed, James Sr. fell into a period of financial distress and was forced to sell the entire collection to UT. Bryan still remembers the day in 1966 that his father called to break the bad news.

“I was devastated,” he says. “And I realized that if I was going to have a collection, I was going to have to get my own.”

That’s just what Bryan did. While working in New York as a banker, and later in Houston as the founder and CEO of Torch Energy Advisors, he began assembling a collection of rare Texas artifacts that would eventually eclipse his father’s. (He also spent millions of dollars buying and restoring the Gage Hotel, in Marathon, where he and his wife own a 50,000-acre ranch.)

That collection, now comprising over 70,000 items, went on public view in June at the new Bryan Museum, in Galveston, which occupies the former Galveston Orphans’ Home, a grand Renaissance Revival pile on Twenty-first Street and Avenue M. Built in 1895, the building was ravaged by the Great Storm of 1900; to raise money to repair it, philanthropist William Randolph Hearst hosted a three-day charity bazaar at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel that featured a brief speech by Mark Twain.

Bryan bought the building in 2013—no longer an orphanage, it had been in private hands for two decades—and spent the next two years restoring its faded luster. Among the objects now on display inside its ocher-colored brick walls are a 1542 first edition of Cabeza de Vaca’s La Relación; a sword used to capture Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto; and a vast armory of rare pistols, rifles, and bowie knives.

The version of Texas history told by the Bryan Museum is a swashbuckling, unapologetically inspirational tale. Bryan himself has little use for the kind of warts-and-all revisionist history embraced by academics. “If you try to tell history, it’s exciting, it’s high adventure, it’s wonderful,” he says. “We’re not here to talk about what people can’t accomplish; we’re here to talk about the exceptional things that people can do.”

The stories of red-blooded Texans like Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, and Bryan’s ancestor Stephen F. Austin are, he believes, just the sort of thing our beleaguered country needs. “We all know our failings,” says the 75-year-old. “Why not get some inspiration? You’re not going to do that by trying to defame your heroes.”