A jab or pain above my right hipbone meant morning had come for me, no matter that I could see stars in the plum summer sky through the window. I rolled over on my pallet on the floor of the upstairs room, trying to settle into a position for a few more minutes’ sleep. I could hear the electric fan humming on the floor and felt a wash of cool air across my naked body. In hours it would be a typical Texas midsummer afternoon, 1987, my fifteenth Fourth of July Picnic—the sun so hot and the sky so bright that you couldn’t stand to look at them—but for now there was a nice, wet breeze, and I could gaze out the window and bath in starlight, the stuff that makes us all.

The pain hit again. I rolled over onto my knees, straightened up slowly and walked to the window. Abbott, in the middle of Texas, is a smaller town than it was 54 years ago, when I was born a hundred yards from where it was now standing. The sky is still clear in Abbott, the stars look close to the earth, like they did when I was a kid.

I looked at my watch. It was 4 p.m. We had come back from preproduction meetings at the picnic site at Carl’s Corner at about midnight. I must have slept three hours. Not bad. Three of four hours is a good night’s sleep for me. The thought crossed my mind that my wife, Connie, wouldn’t be at the picnic today. In the fifteen years since I had begun these annual concerts, Connie had been at nearly all of them. That first crazy but important picnic in Dripping Springs in 1973, she was eight months pregnant with our youngest daughter, Amy. It made me sad to think of Connie not being around anymore. But we had recently separated again. Apparently, my third marriage was headed toward divorce court, just like my first two.

This time I had stomped out of the house Connie had bought in West Lake Hills on the shore of Lake Austin and said I wasn’t coming back. It was after yet another argument about the same old subjects—I didn’t spend enough time with Connie and our daughter, and I smoked too much weed. For me, the choice came down to staying in the West Lake Hills house with Connie all the time when I came off the road—which meant giving up all my pals who I hung around with on the golf course or in my recording studio—or never going back to the West Lake Hills house again.

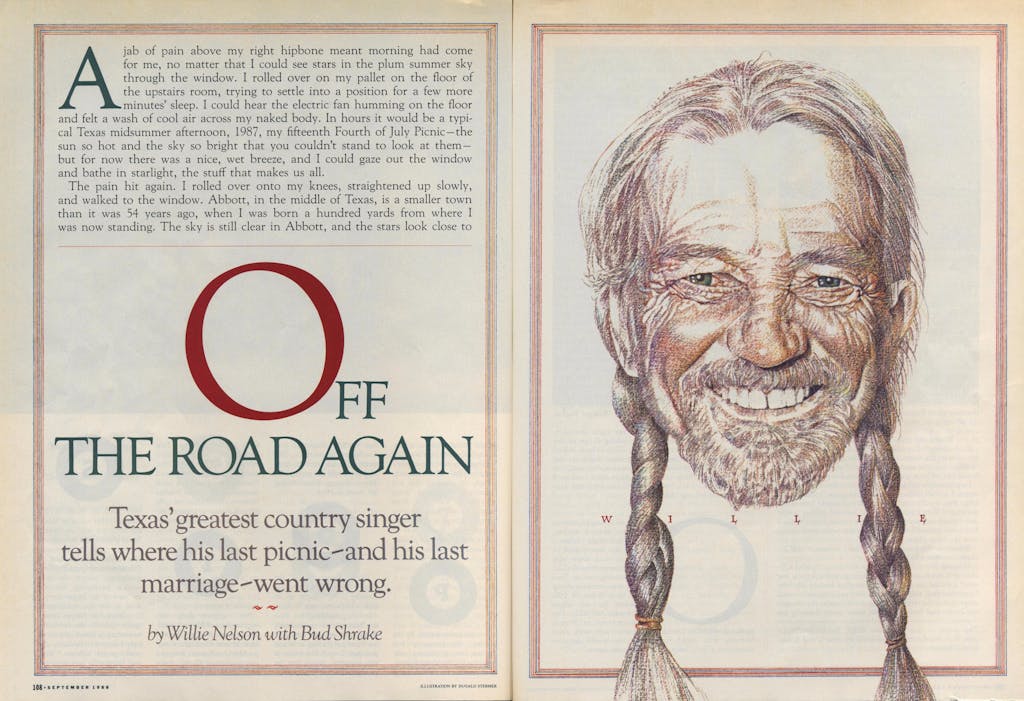

Even though I’ve been married for what seems like my whole life—ten years to Martha, ten years to Shirley, and now eighteen to Connie—I ain’t really cut out to be a good husband and a perfect father.

I am as simple as I look, hard as that may be to understand. I am an itinerant singer and guitar picker. I am what they used to call a troubadour. I would love to be married, I love having a home, but my calling is not compatible with staying put. Sorry to say, I felt the time had come when I had to move on down the road again, into the next phase of my life.

Whatever the next stage is, I don’t believe it will include another wife.

Groping in a pile of clothes on the floor, I found a T-shirt and put it on. It read, “When in doubt, knock ‘em out.” I pulled on a pair of shorts that looked like the Lone Star Flag, stuffed my feet into running shoes, and crept down the stairs, trying not to wake my daughter Lana and her four kids, who were sleeping on their pallets in what will be the living room when we finish restoring the house like it was when Dr. Sims owned it. Dr. Sims and his wife lived in this house in 1933, the night the doc was fetched by my cousin Mildred to tromp across the field to the little frame house where my mother, Myrle, was laboring to present the world with a new old soul—me.

I had bought Dr. Sim’s house earlier in the year for $18,000 and started fixing it up to look pretty as if did in 1933. I would have bought the house I was born in, but it had been torn down. Only our old bedroom was saved, and it had been moved to the other side of the highway and added to the house of a black family.

One of the first things I did after buying Dr. Sim’s house was set about removing the big signboard outside of Abbott that says Home of Willie Nelson. Me and the old buddy Zeke Varnon got drunk and tried to burn down the sign with gasoline fire, but five gallons only singed those old creosote posts and blacked my name so it looked even worse. At least I showed I was serious. I’m trying to get them to change the sign to Home of the Abbott Fighting Panthers, my old high school team.

I let the screen door close quietly and slipped into the warm, purple morning and began to run. I set a slow pace down the road by the house of my old childhood friend Jimmy Bruce, who still lives on the same street and is now the postmaster. I ran past the old tabernacle – the scene, in my youth, of singing and preaching and playing knuckles-down marbles – and on past the Baptist church across the street, where I sang ever Sunday even though I thought I was doomed to hell, and way deep into the fields of Abbott, home of my heart.

I ran toward Willie Nelson Road, a stretch of country road between Abbott and West, the town where I first played in a band when I was about eight or nine years old. It was funny to think about this road being named after me. If they’d named it for me fifty years ago, when I walked down this road to go pick cotton, they might have called it Booger Red Boll-evard. Booger Red is what they called me back then.

The sunrise began to glow on my right shoulder, clods of earth and brown shoots taking shape in the growing light. I felt a real déjà vu. This is how it had looked when I walked these same fields during the Great Depression with my grandmother and my sister, Bobbie, filling our burlap bags with cotton. I turned and ran back toward the house and the sunrise over my left shoulder.

On a soft spring afternoon a few months earlier, the kind of day when I open the moon roof of my car and lower the windows and thank God for putting me in Texas, I was cruising along the back roads of Hill Country in my silver Mercedes 560 SEL – I’ve always loved to drive a good car whether I could afford it or not – with Zeke Varnon, who could have been the world domino champion if he’d been willing to leave home.

Zeke was drinking a beer and scratching the stubble on his chin. We had been up most of the night playing dominoes and passing the tequila bottle back and forth in Zeke’s trailer house in Hillsboro. I’ve been close friends with Zeke since my teens, when we’d decided we were both insane, by the standards of the time. We love being insane. We thought of ourselves as true rebels, living strictly by our own rules. Of course, when we had a sick hangover and a nagging piece of memory about some outrageous act we’d pulled the night before, it helped a little to think of ourselves as rebels instead of just nuts.

“Willie, there’s a guy you ought to meet,” Zeke said after we had been driving a while.

I had been looking out the window at fields where forty years ago I had picked cotton and baled hay. I was remembering when cars first got air conditioners after World War II. I would look up, sweating like a dog in a field, and see cars zooming down the highway in the middle of the summer with their windows shut. That, for me, was what it meant to be rich – to drive down the highway in the middle of the summer with your windows shut.

“Who?” I asked.

Zeke began to tell me about Carl Cornelius. Talk about crazy. Listening to Zeke, I knew Carl Cornelius was some kind of brother. Actually, he was living one of my biggest fantasies: he owned his own town. I’ve always wanted my own town. We’d built me a town in the hills outside Austin – an authentic, one-street Old West town like Texas in the 1880’s – for our movie Red Headed Stranger and for the Pancho and Lefty album video I did with Merle Haggard and Townes Van Zandt. But when the cameras quit turning, the citizens of my town went away, leaving the paint to fade and the brush to blow across the dirt road.

Carl Cornelius, however, owned a real town and his own gang of law officers who dressed like state troopers.

Until eighteen months ago, Carl’s Corner had been just a big truck stop and café. But Carl dreams big. He took the circus-size ten-foot polyurethane musical frogs down from the roof of a fancy Dallas disco and put them on top of his truck stop. He erected a drive-in movie and a sauna and a swimming pool and surrounded them on three sides with a bunch of mobile homes – “changing rooms,” Carl said.

Carl found some backing in Dallas and brought a couple thousand acres of the flat farmland around his truck stop. He made it easy for 180 people to move onto land in mobile homes and stay until they qualified under state law as local voters. At that point, they called an election and voted themselves an official town called Carl’s Corner with Carl as the mayor. Calr owned the liquor-sale permit and the water well and held notes on the land. The only other business in town besides the truck stop was Paula’s Pet Boutique.

Approaching the town of Carl’s Corner in my Mercedes, I saw a thirty-foot advertising billboard rising up from the highway – a huge painted cutout of three figures standing arm in arm and peering out at the landscape. The figures were Carl, Zeke, and me.

“Ah . . . there’s something I ain’t told you yet,” Zeke said.

I parked my Mercedes in the lot crowded with trucks. Zeke led me through the back door. Inside the truck stop I could smell chili, an aroma of comino that watered my sinuses. There in front of a big-projection TV screen, were a dozen truckers eating chicken-friend steaks and cheeseburgers, watching soap operas.

A burly fellow with a big, open country face approached me, his cheeks blooming with whiskey flush, a straw cowboy hat pushed to the back of his head, his belly hanging over his silver belt buckle, crumpled jeans, and ostrich-skin boots. He had a wide, yellow-toothed grin and eyes that looked like they had just been through a sandstorm.

Carl is not bashful. He cut straight to the meat of the matter.

“Hi, Willie,” Carl said. “Let’s have your 1987 picnic right here in my town this Fourth of July. Carl’s Corner is ideal. There is not a single tree to block the view of the stage.

I wasn’t real sure I wanted to have another picnic this year. I say that every year, and I always mean it.

After a bowl of chili and a couple of beers, Carl drove me and Zeke to the picnic site he had picked out – 177 acres of grassland at Interstate 35 and FM 2959, four miles north of Hillsboro. Like Carl had said, there was nothing to block the view – or to block the sun and wind. But the site was within easy driving range of maybe four million people, counting Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, and Austin. We went back to the truck stop and played dominoes in Carl’s office, where he kept glancing at his empire on ten television monitors.

Carl is a good domino player. I am better than good. Zeke is better than me. We all drank from the ample supplies of beer and tequila. At some point during the night Zeke and I were about to win the truck stop and the town of Carl.

I got up to go to the bathroom and took another look around the truck stop. There was lots for sale: sacks of cookies, cans of motor oil, glass unicorns, bronze Western statues, a rackful of books by Louis L’Amour, stacks of trucker logbooks, coffee mugs and T-shirts with Carl’s face on them. There was a jar of peanut butter on every table. Carl had been telling me his plans to open a trucker chapel for prayers and weddings soon, and then a trucker museum and a trucker bank. Your picnic, he’d told me, will put this place on the map.

“Okay,” I said. I admire dreamers, being one myself.

I woke up the next morning on the couch at Zeke’s house. Zeke was standing at the refrigerator, making breakfast, which means, for him, popping the top on a can of beer.

“Do I remember telling Carl he could have the picnic at Carl’s Corner?”

“Yep. She’s all done sealed, partner,” Zeke said. “We’re dedicating it to truckers.”

“We didn’t win the town, did we?”

“Nah, the game sort of fell apart. We’ll pick it up later.”

Carl announced the picnic in newspapers and on TV. Crews shoed up to dig ditches and lay pipe for water. Surveyors were sighting out the parking area. My old Austin Opera House partner, Tim O’Connor, took over as the producer and built a stage, cleared the ground, chose the spots for concession stands and portable toilets. The Hard Rock Café jumped in as official picnic restaurant. Tim started selling tickets. The picnic at Carl’s Corner was rolling with its own momentum.

I climbed on my bus, Honeysuckle Rose, and rode a long way out of town to a series of shows, which I had learned was the best place for me to be while the picnic was being put together. I had, after all, fifteen years of experience with Willie Nelson Fourth of July picnics. They usually ended with me slipping into a plane in the middle of the night and flying off to Hawaii to hide for a week while the damages were assessed. Over the years I had realized it could be an advantage to be unfindable in the weeks before the picnic, as well. The picnic grows beyond control, and I try never to worry about what it out of my control – just to give it my strongest positive thoughts and trust for it to turn out well.

Now I loped back to Dr. Sim’s old house in the early Abbott morning – daydreaming, several voices inside me talking all at once, as they usually do, telling me tales, offering advice; they are my guardian angels mixed in with some malicious spirits. I listen to the voices argue all the time, but my inner mediator makes the decisions unless my ego jumps in front and screws it all up.

Honeysuckle Rose’s generators were humming in the yard as Gator got the bus ready to roll. Gator is a tall, well-built guy with long hair and a beard and unhealthy biceps. He’s a good companion on the road and a conscientious driver who always gets me to the show on time, or the movie set or the recording studio or the motel. I depend on Gator.

I stopped in the kitchen to eat two plums and a bowl of plain yogurt with walnuts and sliced bananas and strawberries on top. I washed down a couple of painkillers with a slug of grapefruit juice, hugged Lana, and talked to my grandkids.

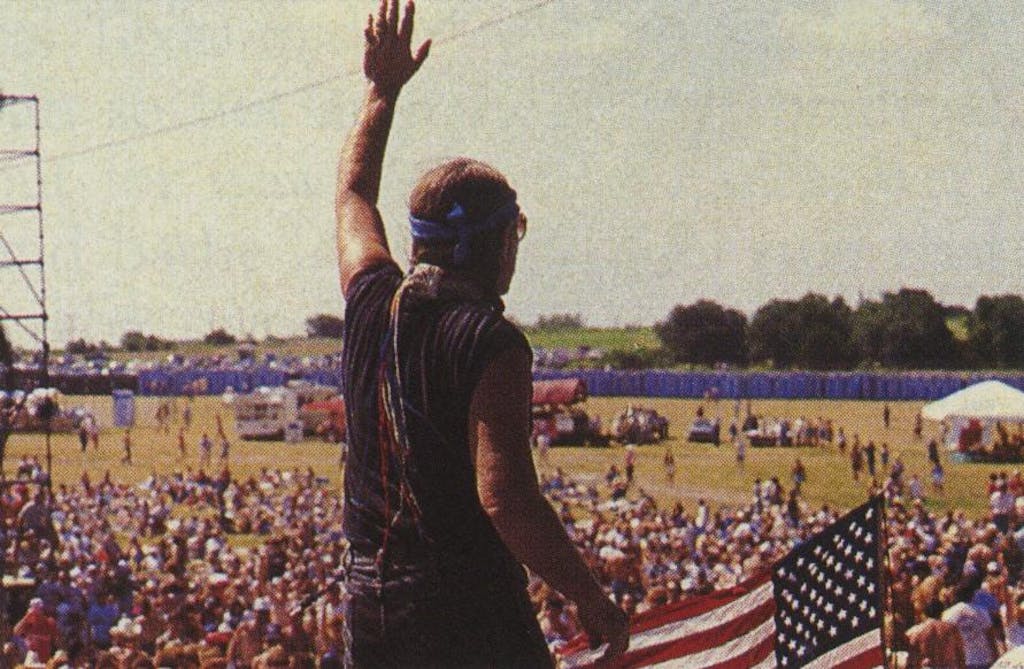

I climbed onto Honeysuckle Rose with a random group of friends. Gator drove us along the streets I ran that morning and headed up the highway until we came upon an enormous Texas flag – I mean it looked like it was ten stories high – and turned down a side road into the backstage area. I climbed out and walked onto the stage to gaze at what he had brought forth.

Beyond the stage the ground fanned out in a field that could hold the 80,000 capacity crowd Carl and Zeke had been predicting in the papers. I was already getting hot. I found myself sweating on stage and not only because of the heat. I had begun to realize that a crowd of 80,000 was a crazy prediction for a blazing 100-plus-degree day out here on this shadeless prairie at Carl’s Corner.

You would have to be a lunatic to fight the traffic of the predicted mob to Carl’s Corner on such a blistering day, no matter that we had loaded the show with Kris Kristofferson, Roger Miller, Ray Benson and Asleep at the Wheel, Billy Joe Shaver, Don Cherry, Stevie Ray Vaughan, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Rattlesnake Annie, Bruce Hornsby, Jackie Kind, Joe Ely, Joe Walsh, Eric Johnson, and had a hell of a show scheduled.

I heard a mellow, husky voice crooning behind me. The voice was singing gibberish – “the old church . . . the bells . . . the yellow house on the corner . . . oh, I am f – ed . . .”

Don Cherry was pacing back and forth at the rear of the stage, rubbing his hands together. Besides being a good, stylish, singer, Don is a scratch golfer who used to play on the pro tour – two qualities that I admire above most others.

“What’s the matter?” I said.

Don stared at me with blue eyes that showed intense concern, like maybe a contact lens had gone crooked.

“Oh shit, Will,” he said.

“What’s wrong?”

“Do you know the lyrics to ‘Green, Green Grass of Home’?”

I thought about it for a moment. I could hear the melody in my head, but the words didn’t come to me.

“No,” I said.

“I’ve been driving up and down the highway for two hours trying to remember that f – ing song. I might have sung it five thousand times in nightclubs. I could walk onstage in Vegas right now, and ‘Green, Green Grass Home’ would burst out of my throat, I couldn’t stop in. But now it’s gone. I can’t remember the f – ing words.”

“Sing something else,” I said.

“Are you crazy? That’s what I open with.”

I left Don huddling onstage with Bee Spears, Mickey Raphael, Grady Martin, and Poodie Locke – stalwarts of my band and crew – all of them singing at the same time, working on the words to “Green, Green Grass Home.”

At 10 a.m. my band and I kicked off the show to a couple hundred folks who camped below the stage with folding chairs, umbrellas, and coolers. I recognized many of them, people I had seen at my outdoor shows in Texas for twenty years, aging hippies like me with earrings and tattoos and women with hair under their armpits. They danced and waved their hands. A big Viking woman in a green undershirt pulled out two breasts the size of volleyballs and bounced them in her palms while her biker old man screamed with toothless joy.

I introduced Don Cherry at 10:30 in the morning. Looking cool, loaded with big-time nightclub aplomb, Don snapped his fingers and swung into “Green, Green Grass of Home.” He sang that song as good as anybody could sing it, like he was headlining the song to a sellout crowd at a star hotel on the Strip in Las Vegas.

The aging hippies listened with a sort of bemused curiosity. When Don gave it his show-biz finish, they sat and looked at him like he was a Hottentot. The crowd – if you could call it that – clapped politely and began to yell, “Let’s boogie!”

Instead, Don sand them a patriotic song about what this country means to him and every true American within hearing. This time the people cheered and whistled when he finished with his arms out-stretched and his head held high. Pro that he is, Don bowed and fled the stage while they were still whistling – we call it getting out of Dodge.

“F – it,” he said as he passed me on the steps. “Which way is the airport?”

By the middle of the afternoon the temperature was 103. The wind had started blowing hard enough to flap the banners on the stage so they sounded like horse-whips cracking – it was some relief from the heat. The crowd had grown to about 4,000. It was clear the prediction of 80,000 had been nuts.

Darkness fell. My old pals Kris Kristofferson and Roger Miller showed up. Kris was, as usual, in an uproar. In the newspaper that morning had been a story that accused Kris of throwing away a plaque some Vietnam vets had given him after he played a benefit for them up East the night before.

“How could they say such shit?” Kris yelled. “In all the confusion backstage, I didn’t know the plaque got left behind. For God’s sake, I’m on these guys’ side, I’m busting ass for these guys. I’m not gonna do anything stupid and humiliating like throw away their plaque!”

Kris is, of course, one of the best songwriters of all time. He shows more soul when he blows his nose than the ordinary person does at his honeymoon dance. But “commercial” is a word Kris refuses to hear. He has written a lot of hits and some standards, but he writes what he wants and sings what he wants – even if the record labels drop him – and for my picnic he was going to do his new song about the Sandinistas in Nicargua and about Jesse Jackson. By then the night wind had dropped the temperature into the 80’s and the crowd had grown to an estimated 8,000.

My manager, lawyer, and accountant arrived, counted the house, looked at the bills, and slunk around with subdued and mournful expressions. The picnic stood to take a $600,000 bath.

Zeke was a partner for profits but not for losses. That was understood from the start. I would never put Zeke in a loser. The money to pay for the losses would have to come from Tim, Carl, and me.

Carl got drunk as soon as he saw the size of the afternoon crowd, had slept it off, and he was back abroad Honeysuckle Rose, telling me with all the certainty a 47-year-old guy born in Kleberg County in South Texas, father of seven children including an infant, could muster that in another hour we’d have a crowd of 50,000. He hit the tequila again.

“Want to play some dominoes?” Carl asked.

“Mix ‘em up,” I said.

Carl stirred the dominoes on the table, and we began drawing hands.

“What’ll we play for?” Carl said.

“Your town.”

“Shit, you own it already. Let’s play for cash,” Carl said.

I went onstage with my band to play the last set at 2 a.m. I couldn’t tell how many people were listening down there in the dark. I knew I was going into the tank financially on this picnic. We had made some major miscalculations, but none of that mattered when we struck up “Whiskey River” to open the final set. That was only money – this was music. The excitement I felt at that moment was too powerful to carry a price tag.

Standing in the spotlights, with the old stars above me in the Abbott sky, I saw the satellite TV truck sending our picture and our music all over the cosmos. And from that stage at Carl’s Corner I could see, too, the dark blanket of the fields where little Booger Red had picked cotton and busted his back bailing hay so many, many years ago.

Regardless what this 1987 picnic may have cost me, in the end we wound up with a good permanent concert site not ten miles from the barbershop where I used to give shoe shine and a song for 50 cents. How’s that for using the creative imagination?

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson

- Kris Kristofferson