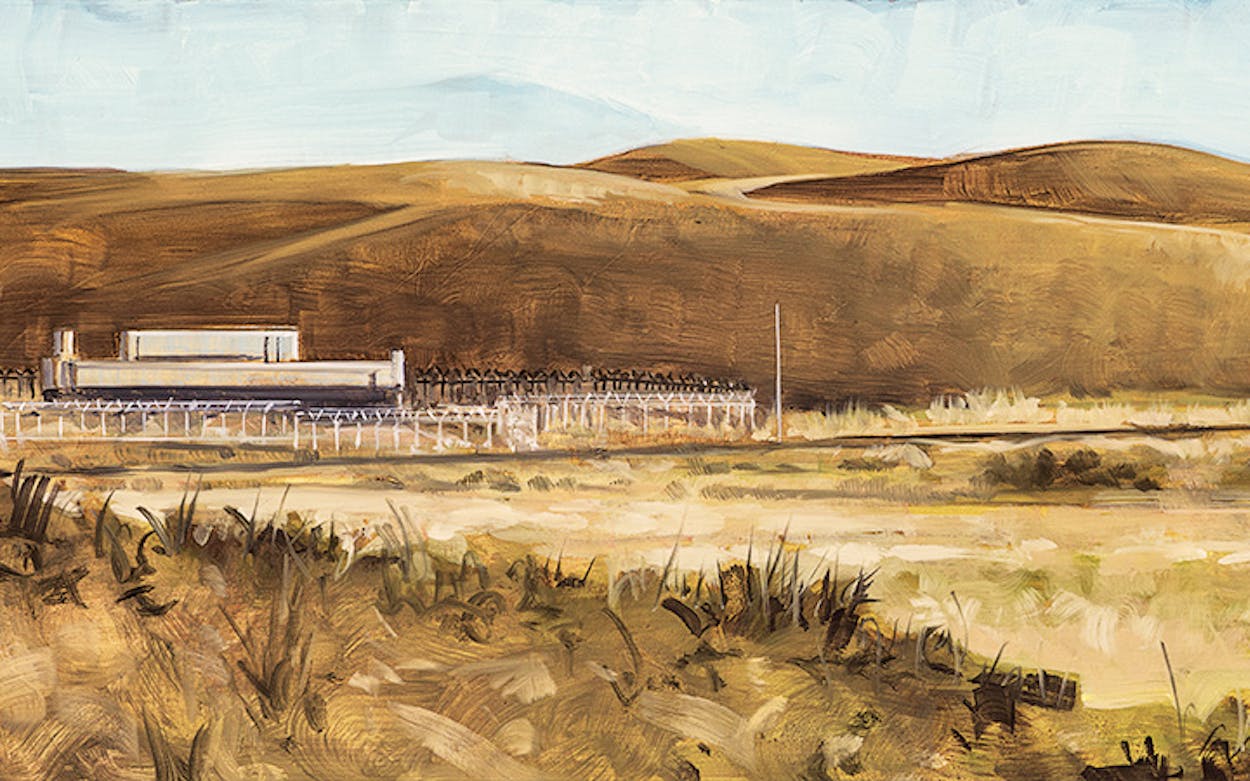

Adam Sternbergh’s third novel, The Blinds (HarperCollins/Ecco, August 1), is something of a mash-up: a revisionist western adorned with futuristic neuroscience and tricked out with some Lost-style puzzles (all of which, rest assured, are solved by the book’s end). Set in an unidentified stretch of West Texas, this gripping thriller follows the goings-on at Caesura, a fenced-off compound that houses a few dozen participants in a federal witness protection program. The twist is that all the residents have had their memories erased, so no one knows which of them were innocent bystanders and which were bloodthirsty perpetrators. And when some of Caesura’s residents start turning up dead, those long-dormant questions take on a fresh urgency.

Sternbergh, who lives in Brooklyn, is a contributing editor to New York magazine.

Texas Monthly: Why did you set this book in Texas?

Adam Sternbergh: To me, Texas is one of the great mythical landscapes of America—as is New York City, where my other books are set. I mean that in the sense that it’s both a real place and a place that looms large in our collective mythology. Once I knew this was going to be a book set in the West, broadly defined, I knew there was no other place to set it than Texas.

TM: Could you be a bit more specific about what role Texas plays in our national mythology?

AS: Sure. I grew up in Canada, but I was born in the U.S., and I was obsessed with American popular culture. There were certain places that always loomed large in popular culture and as a result in my mind. One was New York City, which seemed a little like the Emerald City, from the Wizard of Oz, and one of course was the idea of the frontier, and to me the frontier will always be Texas. I know that the actual Wild West depicted in pop culture encompasses a lot of different places, but to me Texas is the heart of it. And the great Westerns that I loved took place in Texas, or at least claimed to take place in Texas.

TM: What kind of research did you do to try to get the sense of place right?

AS: It’s funny. On the one hand, I feel like I’ve been researching it my whole life, by watching westerns and reading books that gave me a sense of Texas. But there was a point where I thought, “Okay, I need to actually go to West Texas.” I’d been to Austin for a wedding but never anywhere west of there. So I looked on Google Maps, flew down to Dallas, got in a car, and basically drove for three straight days in a loop between there, Abilene, and Amarillo. I went to a town called Matador, and I did a drive up a highway that had a bunch of ghost towns on it. The thing that I couldn’t anticipate, even having planned out the trip ahead of time, was just how far apart everything is. You know, it can take me three hours to drive thirteen miles from the bottom of Manhattan to the top. In West Texas, it can take three hours to get from one town to the next one. That was kind of valuable to me, to get a sense of the landscape. And there was the sense of isolation. When you’re on the highway between Abilene and Amarillo and you’re a hundred miles from the last town and a hundred miles from the next town, you feel very, very alone. That was really useful to me, and something I tried to inject into the book.

TM: The Blinds is a Western of a sort, though I suspect some people will have to squint a bit to see it that way. It sure seems to me that in the last decade or so, the Western has undergone something of a revival. If that’s right, any ideas as to why we’re seeing this renewed interest in the genre?

AS: Oh, I think you’re definitely right. The book was inspired by the classic Western setup, the idea of the town on the far edge of the frontier where people would go and have the opportunity to reinvent themselves, and the town would have to come up with its own laws and its own customs, have the opportunity to start a little mini-civilization from scratch. I feel like at this current moment there’s this interest in the idea of the Western, in the idea of civil society: how do people react when they aren’t held by the usual rules of civilization? When we’re left to our own devices what sort of things start to surface in people? I feel like that has reinvigorated people’s interest in classic Westerns and the whole idea of the frontier as a place where we start from scratch and try to get along with each other.

TM: About halfway through The Blinds, I thought, “This is a book written by someone who was really pissed about the last episode of Lost.” I mean, you’ve got these people trapped in this place, we learn their back stories slowly, there’s a mysterious organization pulling the strings from behind the curtain, but there’s also clearly going to be an explanation at the end of the book that will make sense of everything—which I thought was not the case with Lost, which ended with the writers basically throwing up their hands. Was Lost on your mind when you wrote this?

AS: Its funny, you’re not the first person to make that comparison. But I’ve never seen an episode of Lost. I was one of those people who, by the time the first season had ended and everyone was talking about how great it was, I thought, “I’ve got to check out this show,” and then suddenly people were saying, “Oh, I’m not sure it’s all going to come together.” So then I’d say, “Oh maybe I shouldn’t check into it.” Then they’d say, “Oh, no, wait, it’s fantastic.” I was always one cycle behind and I never got around to watching the show from the beginning.

I am, however, very invested in the idea of narrative closure. I knew that with this book, one way or another, you would have to find out all the answers. I didn’t want to leave people hanging in midair.

Lost is definitely something that’s up my alley. Maybe one day I’ll invest the 220 hours or whatever it would be. But now that I know that a lot of people didn’t really love where the show ended up, it’s really hard to sit down and start with episode one and go all the way through it.

TM: Who’s better—Cormac McCarthy or Larry McMurtry?

AS: Oh that’s a good question. Definitely Cormac McCarthy. I have another confession to make: I have never read Lonesome Dove, even though I have a big fat copy of it on my bookshelf. I have read a great deal of McCarthy—his shadow looms over this book, or maybe his blood spatters are splattered all this book.

TM: Have you read any McMurtry?

AS: I have not. We did a thing at a magazine I worked at once, where we had people recommend their favorite beach read, something they couldn’t put down, and it was striking to me how many people said Lonesome Dove—maybe five out of eighteen people. So I immediately put it on my “to read” list. But I have yet to read it.