Three weeks ago, as the Texanist and I prepared to make one of our occasional long walks to the ramen house—there’s no euphemism there; your fair Prairie Sage is a committed devotee of Asian noodle bowls—he asked if I was Facebook friends with a man named Scott Newton. My ears perked instantly. As the Texanist’s longtime colleague and onetime roommate, I know him to be a man of myriad unsung talents. He mixes a mean, predawn Bloody Mary. He can roller-skate backwards and is a crackerjack wakeboarder. He also happens to possess a keen eye for noteworthy Facebook posts, typically of the ill-advised, overshare variety.

But this recommendation was different. “Scott Newton is the photographer who shoots at all the Austin City Limits tapings,” he said, “and he’s gone crazy posting two or three pictures a day on Facebook. Willie, Waylon, Townes, Jerry Jeff, everybody. He’s creating this online exhibit of Austin music history. It’s amazing. You need to go ‘Like’ Scott Newton Photography and check it out.”

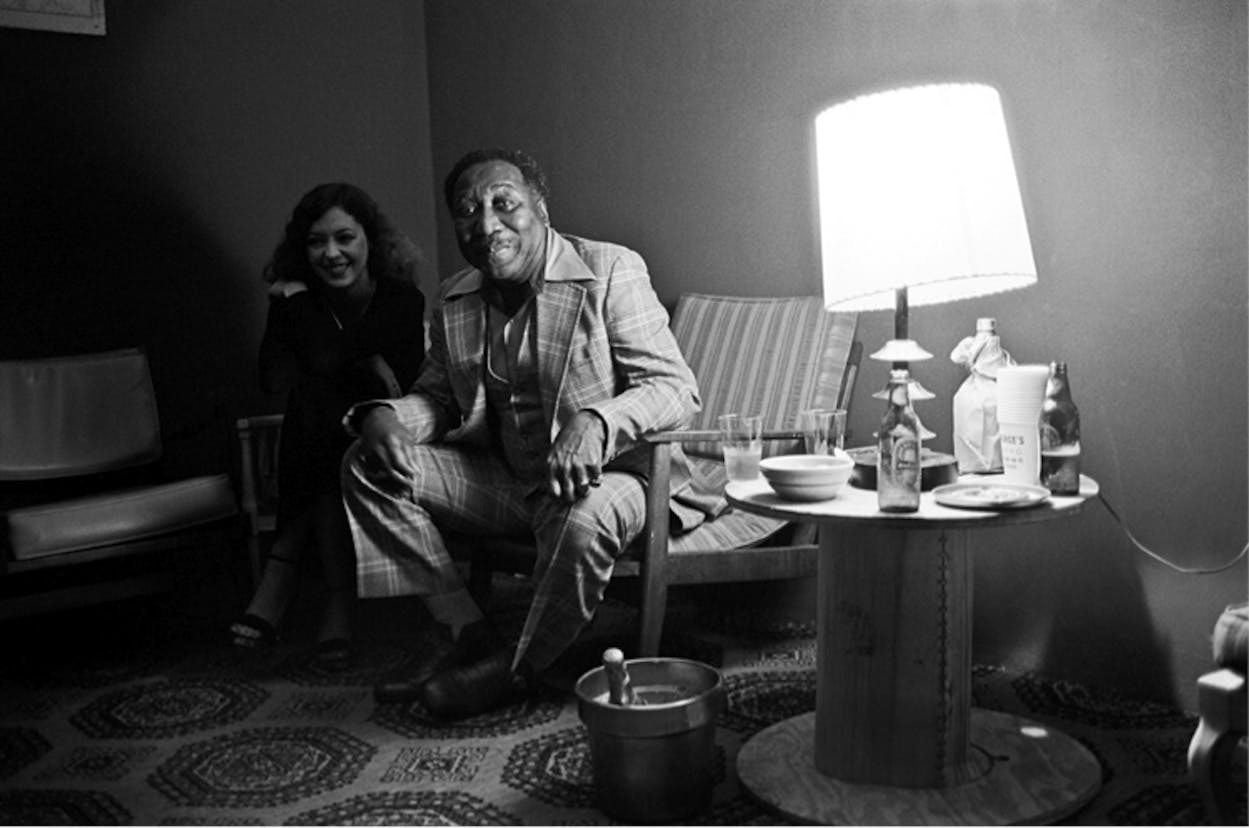

Fine advice, indeed. Though Newton had been posting only a couple of weeks, that afternoon I lost an hour scrolling through dozens of photos. The scope was even bigger than the Texanist had indicated. There were plenty of seventies-era shots of Austin musicians, some celebrated, some overlooked, like Doug Sahm attacking his guitar at the Armadillo and Uncle Walt’s Band harmonizing at Castle Creek. But just as many photos were of touring acts winging through town. There was Fleetwood Mac, falling into a groove at an outdoor show on Lake Austin. And Jimmy Buffett enjoying a beer at a picnic table at Liberty Lunch. And Muddy Waters hamming it up backstage at the Austin Opry House. This wasn’t just the Austin music scene taking shape; this was the outside world first taking note.

Newton’s page quickly became a reliable stop on my periodic procrastination forays. A week later I noticed that the Texanist and I weren’t the only ones catching on—Newton’s number of followers had grown to two thousand. The Selvedge Yard, a well-curated, highly trafficked, photo-driven blog that celebrates stuff dudes like—lots of vintage bikers, sex bombs, and Steve McQueen—ran a collection of Newton’s greatest hits. Curious about the reaction he was getting, I called Newton, who was enjoying the newfound attention. He invited me to his house for a tour of his digital archive.

A chatty guy with a square face and a gray mustache that he’s letting spread into a beard, he’s an iconoclast of the South Austin hippie variety. He likes to talk philosophy and inspiration, and he’s quick to point out that he moved to town the same week in 1970 that the Armadillo World Headquarters opened. Officially he came to study English lit at the University of Texas, and he earned a degree, but he says the more formative university experiences were falling in love with ancient Greek and working in the photojournalism department. He started carrying a camera around. He got good-paying gigs taking pictures of politicians.

But the photos he took for himself were of musicians in a fledgling club scene that was just then building a national reputation. He was a fixture at venues like the Armadillo, Soap Creek Saloon, and the old Saxon Pub. In 1977, when Willie Nelson opened the Austin Opry House with Tim O’Connor, who’d owned Castle Creek, they invited Newton to be house photographer. “Tim called specifically with the idea of creating this warren for artists. The ’Dillo had done that, moved in artists like Michael Priest and Jim Franklin. But I was the only one Tim got to do it. I had a dark room there and complete access to the artists. That first year, Tim booked great, national acts, like Tom Waits, Muddy Waters, Bonnie Raitt. And anytime money got tight he’d book Willie for a week.”

He thought of himself as the phantom of the Opry House, sticking to the shadows backstage and during performances. “I wanted to get that moment when an artist touches the divine. Reading ancient Greek had opened my eyes to the idea of the muses interacting with humans. The current way to say that is to call someone ‘in the flow.’ Like when an athlete is in the zone. It’s that moment of no ego, of merging with the task, when your eyes roll back in your head and you’re completely unaware of what you’re doing. Athletes do it. Musicians do it. That’s what I shoot.”

His time at the Opry House was relatively short. He shut down the darkroom in late 1982, after O’Connor turned the booking over to another company. But by then he’d signed on to shoot for Austin City Limits, the job he still holds, and was firmly established as one of Austin’s top photographers. In the coming years, he’d capture the evolution of ACL from country music showcase to its current status as American television’s most important live-performance program for music of all stripes. He also kept lurking around Austin’s other stages, chronicling Willie’s picnics and the rise of local acts like Stevie Ray Vaughan, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, and the Texas Tornados.

For a long time, his photos were hard to find. They lined the walls of the KLRU studio on UT’s campus where ACL was taped, but those tickets were limited and tough to get. In 2011 his photos reached a bigger audience when they were hung in the new, public venue that’s home to ACL, adjacent to the W Hotel. And the W itself, in a wonderful nod to old Austin, put a Scott Newton print in each of its rooms.

And then he found Facebook. His plan is to keep scanning and posting photos in rough chronological order until he reaches present day. So far he’s up to 1982, just closing out his Opry House tenure. His Facebook strategy is pretty simple. “People have told me I should watermark the photos to protect the images. But I’m not worried about them getting out in the world. What I’m after is an audience, people knowing who I am and what I’ve done.”

Below are some of his photos, accompanied by recollections. If you see something you love, you can go to scottnewtonphoto.com and buy yourself a print. Or just follow the Texanist’s advice: find Scott Newton Photography on Facebook and “Like” it.

I shot Willie that day wearing his Stardust regalia. I don’t know where he was going afterwards but there he was, in his car. So I asked him to stop and said, “Can I take your picture?” He said, “Okay,” and it’s become one of my most famous shots. I didn’t think it was out of the ordinary until the owners of the W were looking for images to put in the hotel. They liked it. Before that this just resided in one of my notebooks.

I shot Willie that day wearing his Stardust regalia. I don’t know where he was going afterwards but there he was, in his car. So I asked him to stop and said, “Can I take your picture?” He said, “Okay,” and it’s become one of my most famous shots. I didn’t think it was out of the ordinary until the owners of the W were looking for images to put in the hotel. They liked it. Before that this just resided in one of my notebooks.

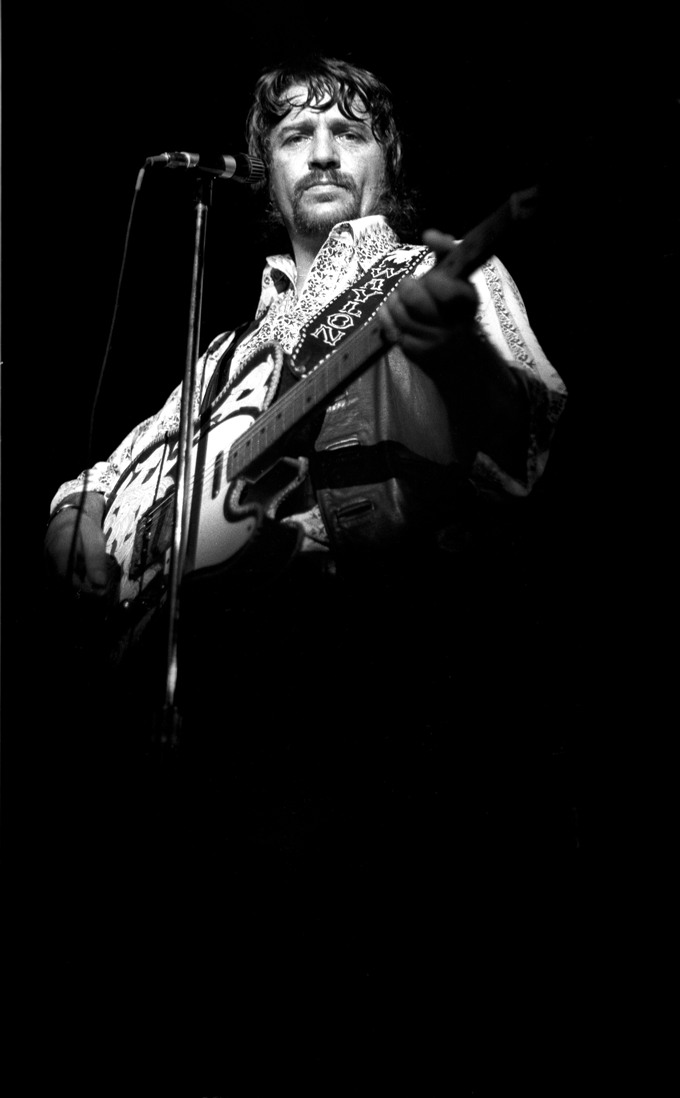

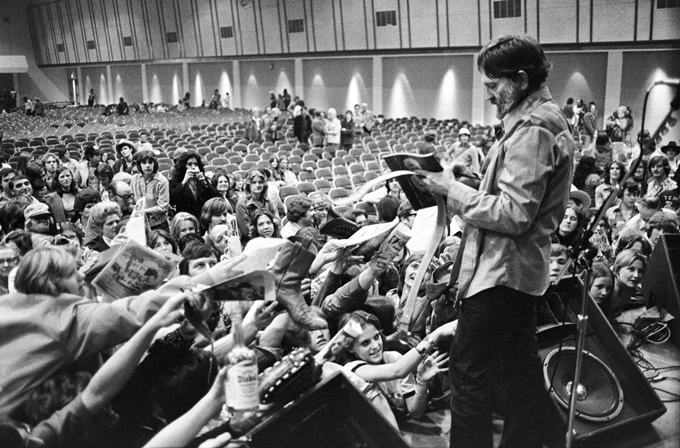

Waylon Jennings, ornery and mean. That’s from the Armadillo. I walked in and all the other photographers were cowering away from the stage, so I went up there and shot some pictures. And he was looking at me like that. Somebody said, “You know, he just kicked [a photographer].” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah, he kicked her camera.” I said, “No shit?” Waylon didn’t like cameras.

There was Jerry Jeff and there was Jackie Jack, and you had to know which one you were talking to. Because one was this charming Scamp Walker character. But the other would fly off the handle, start screaming and yelling and piss in your beer.

Jimmy Buffett used to hang around Austin a lot. This was in 1974, at Liberty Lunch. It had been the old Calcasieu lumberyard and still had lots of their stuff around. This wasn’t the day he wrote “Margaritaville” [which, according to legend, happened one afternoon at an Austin bar], but it was supposedly the same trip. The guy to his left is Roger Bartlett, who Buffett invited to join his band that day. He said, “You can be my first backup guy, my first Coral Reefer.” He’d clearly given this a lot of thought. I sent Buffett a copy of this photo to sign for me, and he wrote, “Hide this photo.” I realized, of course, that now he’s got his own brand of beer.

Jimmy Buffett used to hang around Austin a lot. This was in 1974, at Liberty Lunch. It had been the old Calcasieu lumberyard and still had lots of their stuff around. This wasn’t the day he wrote “Margaritaville” [which, according to legend, happened one afternoon at an Austin bar], but it was supposedly the same trip. The guy to his left is Roger Bartlett, who Buffett invited to join his band that day. He said, “You can be my first backup guy, my first Coral Reefer.” He’d clearly given this a lot of thought. I sent Buffett a copy of this photo to sign for me, and he wrote, “Hide this photo.” I realized, of course, that now he’s got his own brand of beer.

This is one of the Band’s last live performances before The Last Waltz. They played Sunday Break II [an outdoor festival in Austin] in July and had a tour booked for after that. But there was a boating accident while they were down here, and Richard Manuel broke a bone in his neck. So they canceled the rest of the tour.

I love these guys. As soon as they started playing, as soon as the music started, they all began jerking around. Like they were synchronized. I realized, “Oh my god, there’s something else that’s playing them.” It was the first time I ever looked at a band and saw the whole elephant. Since then, because they showed me how it works, I always tried to convey the whole elephant. Not just the pieces. Not just five guys.

There’s Doug Sahm, coming out of black. That’s my style. Sometimes, if you pull an image out of static, you can make it into a statue, make the artist immortal. Doug knew what I was doing. The muse burned bright in him.

You know the Doug stories. He was a child prodigy, played with Hank Williams, did the San Francisco scene, showed up in Austin. And as Jerry Wexler said after he came down to check out the Austin scene for a week, “There’s a lot going on, but the only two worth a shit are Willie and Doug.” That was true.

To this day, Willie’s drummer, Paul English, is the sweetest guy in the world. But he used to love that devil’s cape. And he wasn’t shy about telling stories about the days when he was Willie’s enforcer. It used to be just Willie and Paul, playing the bars and lounges, big and small. And when promoters didn’t want to pay, Paul was the muscle.

Elvis Costello at the Opry House in 1978. His energy onstage was different from anything I’d ever seen. It was like he was at hummingbird speed. He lives at a different frame rate, to put it digitally. And Austin’s response was amazing. After the show he hung around town a while, and the story was that he considered moving here. That would have changed everything.

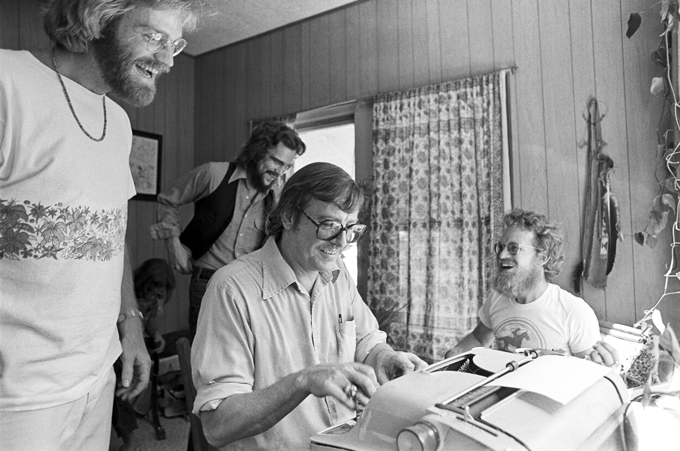

That’s Bud Shrake at the typewriter with the Gonzos: Bob Livingston, John Inmon, and Gary P. Nunn [from left]. Bud wrote songs with them under the pseudonym “M. D. Shafter,” but at that moment he was working on a band bio. He’d just written the sentence “Livingston is the most worldly of the bunch and intends to someday visit Houston.”

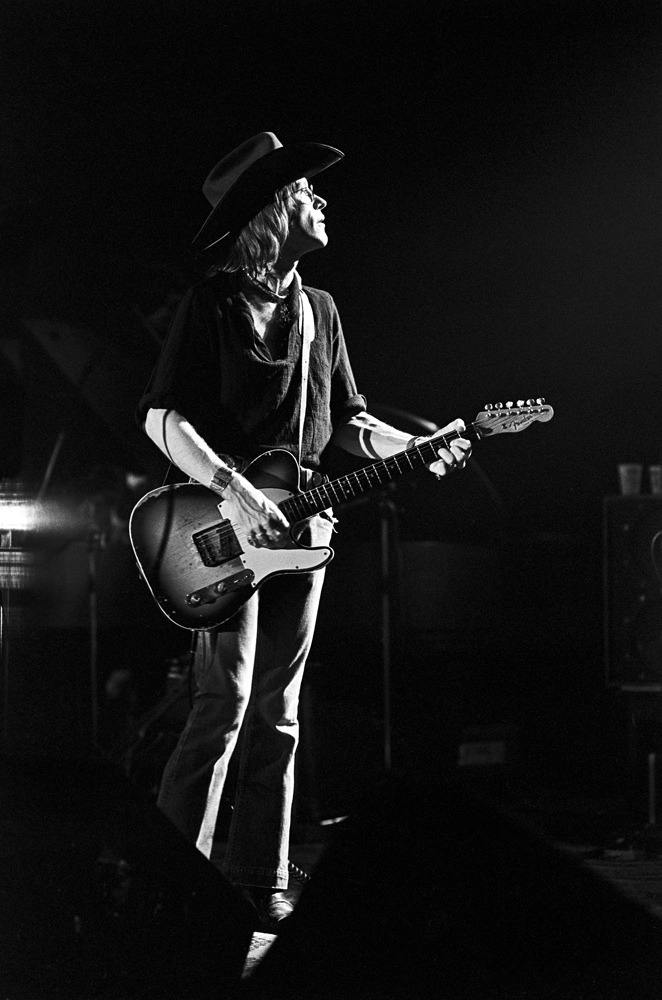

Bonnie Raitt was interesting. When she’s onstage she seems totally sure of herself. She’s an incredible blues slide guitarist, not just the best woman slide guitarist but maybe the best there is. But every time I’ve seen her come offstage, no matter how good the show was, no matter how much the audience loved her, she’s been convinced she’s blown it and started to cry. You can see that when she plays. When the fans are cheering, she really takes off. But there’s always a fragility there.

Bonnie Raitt was interesting. When she’s onstage she seems totally sure of herself. She’s an incredible blues slide guitarist, not just the best woman slide guitarist but maybe the best there is. But every time I’ve seen her come offstage, no matter how good the show was, no matter how much the audience loved her, she’s been convinced she’s blown it and started to cry. You can see that when she plays. When the fans are cheering, she really takes off. But there’s always a fragility there.

The deal with Willie is he’s just as excited about running up and shaking fans’ hands as they are about him. I’ve never seen anybody who gets off on commingling with fans the way he does. He stays and signs everything. This is in Waco, February 2, 1977, and I can remember that because on February 1 my son had been born. So I was eager to get home. Willie had played that night with Dolly Parton, and after the show is over he starts signing shit and shaking hands. It took well over an hour. He never begrudged anybody anything. He smiled for the last person just like he’d smiled for the first.

This is that playful side of Ann Richards that I loved so much. She was in Blanco County, at a Dukakis event in 1988, before she ran for governor. All the good Democrats were there. I saw her get on that Longhorn from a hundred yards away and came running with all my camera gear hanging off me to get this shot. And she yelled, “Scott, don’t you dare take my picture up here, goddammit!” And then she just started laughing. “Goddammit, you got me.”

That’s Tom Waits in the green room preparing to go onstage at the Opry House in 1977. I call this one “Accessing the Muse.” He didn’t really talk much. He was like he was onstage, quirky, but to himself. He didn’t seem to relate to anybody. A little moody. But I didn’t go out of my way to meet him. This was a private, intimate moment.

First time I ever saw Stevie Ray Vaughan was at the Opry House in 1980. He was opening for a Hendrix clone named Randy Hansen. I remember telling somebody, “Hansen does a pretty good Hendrix, but the opening act is amazing.”

This was the procession bringing LBJ’s body down Twenty-ninth Street from the Wilke-Clay funeral home to lie in state at the LBJ Library. I happened to live on Twenty-ninth, and that morning we didn’t know anything about LBJ dying. All we knew was there were soldiers with rifles out on the streets; we thought Nixon had finally gone mad and called in the troops. There were about fifteen minutes there where the hippies were all pouring out of our houses going, “What’s going on?” and the soldiers wouldn’t talk to us. But when we figured out what it was, I ran in the house and put Mississippi Fred McDowell’s “You Gotta Move” on the stereo. We had huge, rock and roll speakers. You could hear it from Lamar to Guadalupe.

I was out at Jerry Jeff’s place and saw that rainbow, and the rest just came to us. When I put this up on Facebook, somebody commented, “Okay, he’s floating on a raft with a drink in one hand, a cigar in the other, and a phone leading to nothing at his ear. Perfect Jerry Jeff.”

All photos copyright Scott Newton.