Let’s get this out of the way at the top: seeking to identify “the very first rock and roll record” is a fool’s errand, one which writer Nick Tosches likened to trying to “discern where blue becomes indigo in the spectrum.” And yet doing so has long been a favorite parlor game of rock scholars. There have been many candidates for this urtext, but if there’s a consensus around any one song, it’s Jackie Brenston’s 1951 single “Rocket 88,” which features a distorted guitar and lyrics about a car: two hallmarks of what was to come. According to Brenston’s bandleader, Ike Turner, “Rocket 88” inspired producer Sam Phillips to seek out white musicians who could sound like black ones, and then one day, wham! Elvis!

A prominent scholarly dissident to this line of thinking was the late blues and rock historian Robert Palmer. In his 1995 book Rock and Roll: An Unruly History, Palmer made the case for another candidate for this pop-culture holy grail: “Rock Awhile,” a 1949 song recorded by an all-but-forgotten teenager from Houston named Goree Carter. Citing its unmistakable resemblance to Chuck Berry’s later work, its lyrical instruction to “rock awhile,” and the way the guitar crackled through an overdriven amp, Palmer argued that Carter’s song was a strong contender for the oldest known specimen of the music that soon after took over the world.

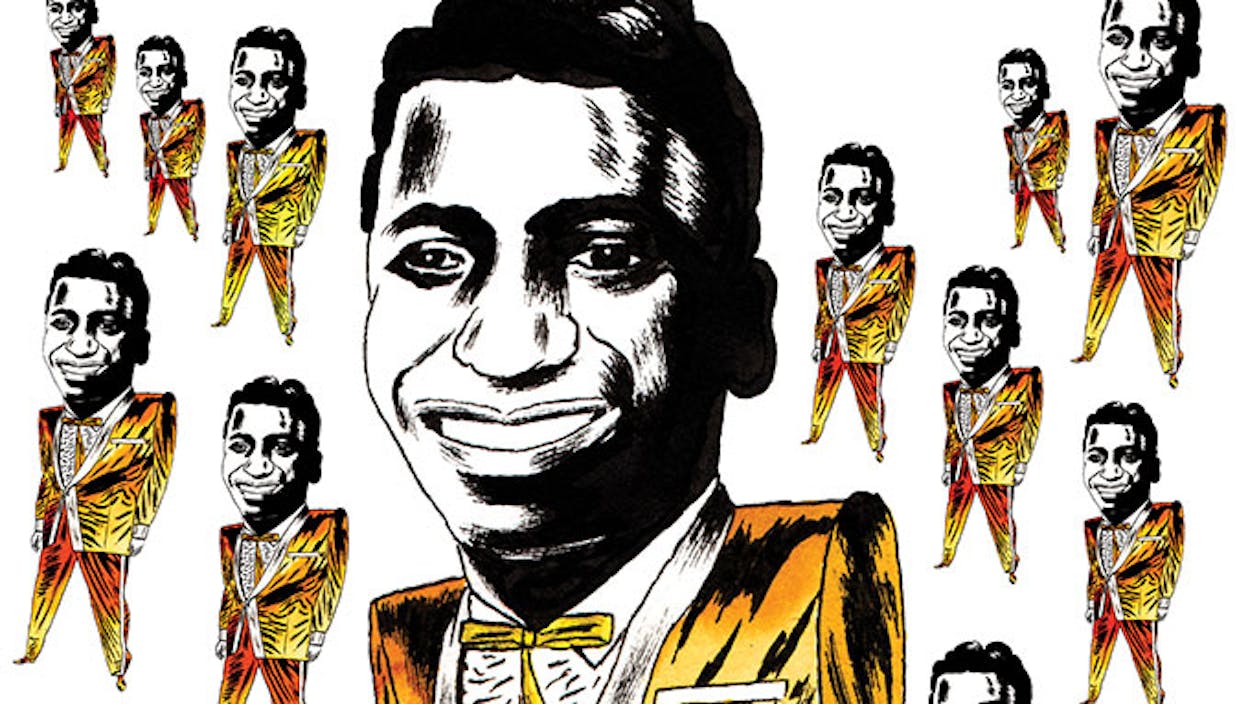

And yet even in Houston, few people remember Carter. There is no historical marker memorializing the house where he lived almost his entire life or the Montrose studio where the song was cut. There is no Goree Carter Day, nor any Goree Carter Avenue. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has not seen fit to honor the man. His name is absent from virtually all standard histories of modern popular music. It’s as if he never lived, never thrilled audiences with his behind-the-back guitar playing, never invented rock and roll.

According to his gravestone, Goree Chester Carter was born on New Year’s Eve in 1931, though most other sources claim he arrived a year earlier. Aside from his brief days as a rising star and a stint as an infantry grunt in the Korean War, he rarely strayed from his native Fifth Ward. His first home, at 1310 Bayou Street, was also his last.

And that home once rollicked. In 1983 Carter told the blues historian Dick Shurman that as a kid he needed to step no farther than his own backyard to hear future jazz and R&B stars like Arnett Cobb, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, and Russell Jacquet. Carter’s older sisters Leverne and Roberta had attended school with the musicians and would invite them over to practice.

His sisters also led him to his muse: T‑Bone Walker, the Linden-born, Dallas-bred pioneer of the electric blues guitar. One sister brought two of Walker’s records home for Carter—“I’m Gonna Find My Baby” and “Bobby Sox Baby”—and he quickly started playing along on the family’s beat-up old guitar. “I listened,” Carter told Shurman. “The next morning, I got up early ’cause it stayed on my mind ’cause I liked the sound, and I got on one string tryin’ to find out how to play like him. . . . Then [I] just moved on along till I could get his chords, and that’s how I picked up his style.” By the time he was a teenager, Carter was fronting bands with a majestic hollow-body Gibson, perhaps purchased with the paycheck he earned hoisting sacks at the Fifth Ward’s Comet Rice Mill.

One night in late 1948 or early 1949, at Houston’s Eldorado Ballroom, Carter came to the attention of Solomon Kahal, a New Yorker and veteran of the Tin Pan Alley scene. At that time, every “race-record man”—as R&B talent scouts were known then—was looking for the next T-Bone Walker. In the Fifth Ward, Don Robey, of Peacock Records, had found his in Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Kahal pegged Carter as his Walker wannabe and signed him to his new label, Freedom Records, which was headquartered on Oxford Street, in the Houston Heights neighborhood.

On an April day in 1949, a band billed as Goree Carter and His Hepcats set up in Bill Holford’s Audiophile Custom Associates Studio at 612 Westheimer to record four tracks. This was Carter’s first recording session for Freedom, and he and Kahal were already butting heads. Kahal wanted Carter, who was only seventeen or eighteen at the time, to hew closely to the T-Bone formula; Carter wanted to take some risks: he wanted to play softer, in the form of jazz and ballads, and harder, as on “Rock Awhile,” which was a departure from Carter’s usual stylings. Where Walker was hyper-suave and elegant, even on his more up-tempo numbers, “Rock Awhile” was uproarious. The song teeters on the brink of chaos without ever quite going over the edge, especially during Carter’s guitar solo and Conrad “Prof” Johnson’s sax solo, which features a madcap snatch of “Jingle Bells.” Pianist Lonnie Lyons holds down the low end with a driving boogie-woogie beat, while drummer Allison Tucker splashes the cymbals with aplomb. And right there at the beginning is the song’s opening riff, which will sound very familiar to anyone who has heard the first few seconds of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” and “Sweet Little Rock ‘N’ Roller,” all of which came out a few years later.

According to Carter, the song that should have made him a legend was dashed off out of necessity. “That was wrote in the studio,” he told Shurman. “I just picked it up because we were short of a record.” Carter said he penned the song in about an hour while the band took a sandwich break. He may have been inspired by earlier songs that had similar beats, some of which mentioned rocking and rolling in the lyrics. But as Palmer pointed out, true rock and roll also needs loud, distorted guitars. “Rock Awhile” was the first song to meet all those criteria.

Sumter Bruton, the lead guitarist of the Fort Worth band the Juke Jumpers and a scholar of Texas R&B, heard “Rock Awhile” about fifteen years after it was released, while he was at Texas Christian University. “I’m a guitar player, a T-Bone Walker–like guitar player,” he says. (He’s also the brother of the beloved late guitarist Stephen Bruton.) “What I liked about Goree was that he played T-Bone-style and took chances and made them work most of the time. Not always—he’d screw up every now and then—but he was a hard-playing motherf—er. He played big, fat chords and he sang well and he had a great band.”

One key member was saxophonist Conrad Johnson, a 33-year-old veteran of Count Basie’s band, who was teaching music at Booker T. Washington High School. Around the time Kahal signed Carter, he also hired Johnson as his in-house bandleader, arranger, and A&R man. Johnson enlisted his more gifted students for studio work, and they’re the ones, in a variety of configurations, playing behind most of Freedom’s R&B acts under a variety of names, including the Hepcats. Well after he backed Carter on “Rock Awhile,” Johnson kept making a joyful noise. By the late sixties, he had moved on to Kashmere High School, a couple of miles north of the Fifth Ward, where he took charge of the stage band, welding fiery funk to the staid big-band sounds that prevailed at the time. Soon enough the Kashmere Stage Band was enjoying repeated victories in national high school band competitions and releasing records; decades later its tracks would be sampled on numerous rap songs. Four years ago the actor Jamie Foxx helped finance Thunder Soul, a critically acclaimed documentary about the KSB and its dapper leader, the man who came to be known simply as “Prof.” Though the KSB’s grooves were very different from what Johnson was up to with Carter, it’s not hard to hear the same precise interplay between horns, keyboards, and strings, the same ability to inject older styles with the newest beats.

Johnson and Carter were part of a thriving R&B scene that put Houston and the surrounding area on the national charts on a regular basis, thanks to figures like Charles Brown, Amos Milburn, Roy Brown, and Arnett Cobb. While neither “Rock Awhile” nor any of Carter’s other singles made the charts, they were successful enough to keep him touring and recording for a while, though he kept working at the rice mill until it closed decades later.

In 1950 Carter went to New York City, where he scouted out sessions, apparently behind Kahal’s back. He told Shurman that he had landed a deal during that trip, though he didn’t reveal with whom. And then he got a draft notice. Carter was shipped out to Korea, where he spent a little over a year as a private first class. If he saw combat there, he doesn’t seem to have talked much about it, though he was in-country when many of that war’s most vicious battles took place.

When he returned to Houston, he couldn’t get the traction he had had before. Kahal had shut down Freedom, and no one else seemed interested in signing Carter. He did occasionally cut sides for a succession of obscure labels under various pseudonyms, but he alienated the one man in Houston who could have made him a star: Peacock Records’ Don Robey. Carter cut a single for Peacock, but it didn’t see release for decades, possibly because, according to Carter, he knocked Robey’s head through a liquor store window in a dispute over a $100 debt.

By 1954 Carter’s recording career was over. “I had a lot [of songs] that I just tore up, and they were good songs,” he told the Dallas-based blues historian Alan Govenar in 1984. “I tore them up because they wouldn’t let me cut them. They said I was ahead of myself. So I destroyed them. If I can’t perform them, then I’ll do like Moses did with the Ten Commandments. Can’t live by it, die by it.”

In 1970 Fifth Ward blues poet Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner told Blues Unlimited magazine that Carter was playing jazz guitar at a spot called Koret’s Smokehouse Lounge. After that, he pretty much vanished. Then, in 1981, Bruton’s Juke Jumpers released a cover of Carter’s “Come On Let’s Boogie” and put word out that they wanted to meet the song’s creator. Among other things, they hoped to bring him the good news that a number of his old recordings, including “Rock Awhile,” were about to be rereleased by a Swedish label and that the label wanted to give him an advance of about $600.

“It was like he had fallen off the face of the earth,” remembers Juke Jumpers guitarist Jim Colegrove. The band got Pete Mayes, a contemporary of Carter’s and a fellow Walker disciple, to ask around about Carter. “And then he comes back and says, ‘Strangely enough, Goree lives with his mama in the house he was born in,’ ” Colegrove recalls.

In July 1982 Colegrove, Bruton, and Juke Jumper sax man Johnny Reno paid Carter a visit at 1310 Bayou. “He was sure surprised to see three white boys on his porch,” Bruton laughs. By that time such visits were shopworn clichés of the blues narrative: legend cuts amazing records; legend sinks into obscurity; white fans track him down decades later and coax him back into the game; legend makes comeback with new generation of fans. So it had been with Son House, Skip James, and Lightnin’ Hopkins in the sixties. So it was not to be with Goree Carter.

Bruton recalls that Carter had no guitar at his house. The living room where they all sat was sweltering, cooled by only a box fan. A black-and-white TV flickered in the background. As the Juke Jumpers and their hero sipped warm beers, Bruton unpacked the same model of hollow-body Gibson that Carter once played and placed it in his hands. “He told me he had arthritis, and you could tell he hadn’t played in a while,” Bruton remembers. “He hit the right notes, but he was real slow, you know?”

Perhaps for that reason, or perhaps because he had simply given up a long, long time ago, the Goree Carter revival never got much further than that. Two years later, Alan Govenar paid his even more depressing visit to 1310 Bayou. “He was withdrawn, not eager to talk, broken down,” he says. “There was a stark loneliness to that room he was living in.” Govenar snapped a bleak photo of Carter in a Red Man gimme cap, tank top, and shorts, his eyes sunken into puffy cheeks, what looks like a child’s cheap acoustic guitar across his lap.

Carter passed away four days shy of his fifty-ninth (or, perhaps, sixtieth) birthday, in 1990. Pete Mayes would later say that Carter was “just tired of living.” Since then, his old home has been torn down. A scraggly cedar and a stand of hackberry trees now preside over the tiny, trash-strewn lot, one of the only empty spaces on a block tightly packed with brightly colored shotgun houses in varying states of disrepair. There’s a constant dull thrum of traffic coming from the Eastex Freeway just a football field or so to the west.

Gone as well is the Audiophile Custom Associates Studio; it’s now a parking lot next to Katz’s Deli. Today, Goree Carter, the man who beat Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and Ike Turner to the feat of inventing rock and roll, is buried in Houston National Cemetery under a slab that lists his name and the dates of his birth and death and his service in Korea. There’s nothing else on the stone, not even a small guitar icon to indicate that Goree Carter had once been a musician.

- More About:

- Music