Like so much else about Leon Bridges, his stage patter is a work in progress. Every few shows he gets up the confidence to say something new to the crowd, to introduce a song with something beyond a simple recitation of its title. At a recent gig at Austin’s South by Southwest music festival, the 25-year-old soul singer from Fort Worth tested out a new introduction to his song “Brown Skin Girl.” “Where are my brown-skin girls?” he asked the audience. A smattering of whoops and hollers bounced back toward the stage.

It might not seem like much, but when he said the line, he loosened his shoulders, leaned back, and flashed a wide grin, as if he’d just impressed himself. Finally, he seemed to be thinking, this rock star thing is starting to click.

Then again, Bridges never got around to introducing his band from the stage. He says he’s afraid that his nerves will override his memory, that he’ll stumble over a bandmate’s name or forget one altogether. “Every show, I’m big-time nervous up there,” he says. “I’ve got so much to learn. It’s all very new.”

The newness of Leon Bridges is at the heart of what you might call his nowness. Going into SXSW, where it’s awfully hard to stand out during an event that boasts more than two thousand artists, Bridges was almost universally picked in press previews as a must-see. His Horatio Alger backstory, which took him from full-time dishwasher to Columbia Records priority, fanned the flames. And after eight SXSW shows, each of which left many disappointed fans turned away at the door, it was clear he could have played twice as many gigs and still not satisfied the curiosity and demand.

If Bridges “won” SXSW, as one Billboard headline put it, that’s partly because fans enjoyed the spectacle of getting to watch a raw talent navigate a steep learning curve. The appeal of the Leon Bridges Story is similar to that of American Idol or The Voice: we root for the most talented but sheepish contestants and cheer as they hone their skills and gain confidence week by week. And make no mistake, Bridges is as sheepish as he is talented. He may get called “the next Sam Cooke” by people who don’t know any better, but he’s modest enough to know better himself.

“Yeah, I can’t be that good,” he says a month or so before the festival, over burgers at Del Frisco’s Grille in Fort Worth, where he had that dish-washing gig a few months earlier. “It’s not possible. I worry I can’t live up to the expectations.”

Of course, this is someone who until very recently had no expectations of signing to a major label or playing to packed houses. Bridges’s introduction to music came when he was a kid hanging out at a Fort Worth community center where his father worked. He watched another student sing R. Kelly’s 1998 hit “When a Woman’s Fed Up” and began listening to modern R&B while his mother was away at work. “She’s a very religious person,” he says. “She didn’t allow me to listen to secular music.” Drawn to the choreography in R&B videos, he started dancing just for fun and, after graduating from high school in 2007, enrolled at Tarrant County College for a couple of dance classes, which gave way to three years’ worth of ballet, modern, and jazz study. He earned money busing tables, and before long he took up the guitar and started writing songs, most of them religious-themed, which he eventually began performing at open-mike nights at Stay Wired, a Fort Worth coffee shop.

“There weren’t many people doing R&B at open mikes,” says Bridges. “Mostly, it was folksy country stuff. And here I was with my iPod, singing over hip-hop instrumentals. I was very different. I think people liked that.”

Those appearances led to gigs at the Magnolia Motor Lounge and Lola’s Saloon and an invitation to record demos for Humble Beast, a Christian hip-hop label. “A producer there asked me, ‘Is Sam Cooke one of your inspirations?’ ” Bridges recalls. “I’d heard ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’ as a kid in Malcolm X but really nothing else. So after he mentioned it, I started digging into Sam Cooke, the Temptations, and older soul songs. And I thought, damn, it would be fun to write this kind of stuff.”

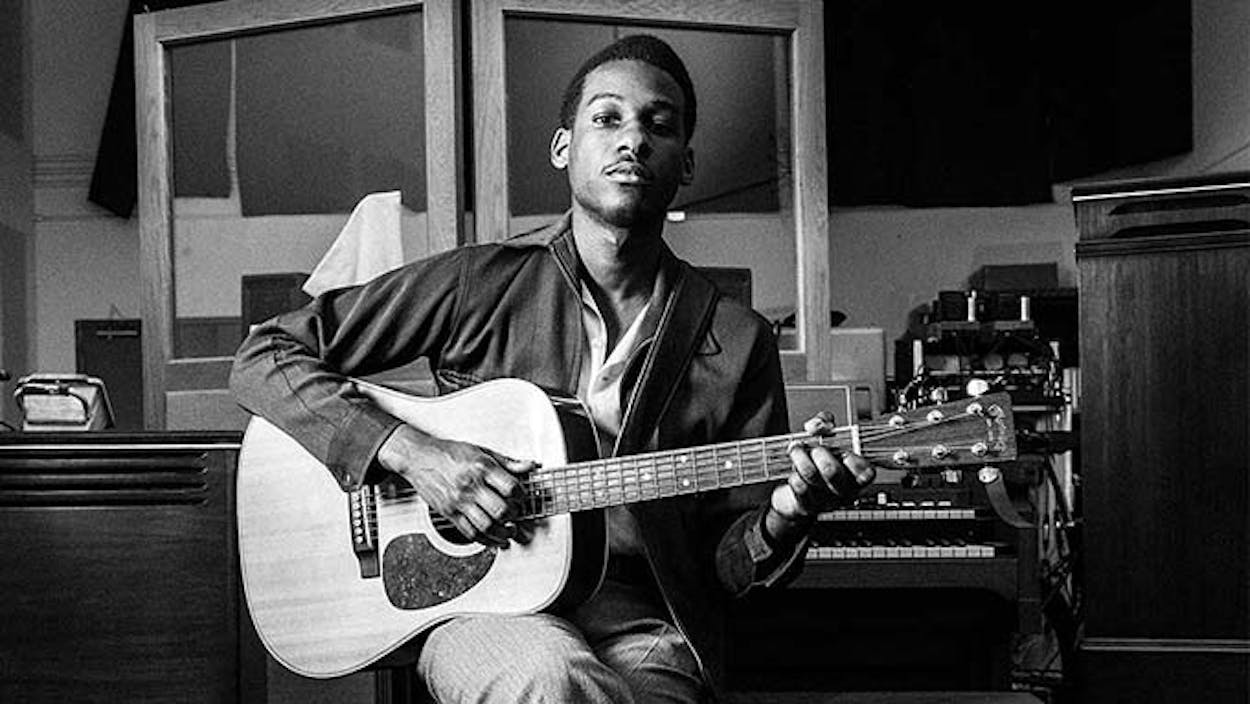

Around the same time, Austin Jenkins and Josh Block, of the Austin indie-rock outfit White Denim, were building an old-school analog recording studio at Shipping & Receiving, a Southside Fort Worth industrial complex that was transitioning into a mixed-use space. One night last August Jenkins’s girlfriend noticed Bridges at a bar, commented that his high-waisted jeans were similar to the kind that her boyfriend fancied, and introduced the two men. A week later, Jenkins caught one of Bridges’s solo performances at Magnolia and immediately offered to record some demos. “His voice blew me away,” Jenkins says. “All I could think was, wow, ribbon mikes are going to sound insane when we put them in front of him.” (Ribbon mikes are those bulky, old-style microphones you used to see on Larry King’s desk, which are prized by producers for their ability to capture details at higher frequencies.)

In October Bridges sent two of the tracks he recorded, “Coming Home” and “Better Man,” to the influential Dallas-based music blog Gorilla vs. Bear. Their success on the website—and on England’s BBC Radio 1—led to an old-fashioned major-label bidding war. It’s not hard to see why: the songs’ warm, Motown-style production and Bridges’s voice—which bounces between smoky and slinky—seem tailor-made for radio playlists that already include Bruno Mars, Sam Smith, and Alabama Shakes. And Bridges’s lyrical minimalism is easy on the ears. On “Coming Home,” he croons, “Baby, baby, baby,” building up to a line you could imagine Sinatra delivering: “The world leaves a bitter taste in my mouth, girl / You’re the only one that I want.”

“The simplicity comes from my innocence to music,” Bridges says. “I don’t know anything about the technical side of recording or songwriting. I’m not an intellectual. I guess my simple thinking translates into straightforward lyrics.”

Already, there’s been some talk that Bridges’s “innocence”—his lack of a deep history with the music he’s playing—undermines his credibility. In February the Dallas Observer ran a piece titled “Let’s Stop Calling Leon Bridges ‘The Truth,’ ” which asserted that Bridges’s appeal was a form of “fetishized nostalgia.” What the piece stopped short of mentioning is the ever-fraught issue of race. With his throwback sound and look, Bridges is the kind of black artist whose existence might reassure white audiences that it’s okay not to like hip-hop, the dominant black music form of the past three decades (even though Bridges himself is a hip-hop fan). And so far his music seems to appeal to mostly white audiences; this summer he’ll open some dates for the indie-folk band Lord Huron.

But it’s also likely that black audiences will eventually recognize his respect for early R&B tradition and show him the sort of love that has buoyed the career of latter-day old-style soul men like Anthony Hamilton and Maxwell. Ultimately, it’s a good guess that the evangelical response Bridges has drawn says less about race than it does about his tenderness and vulnerability, which are palpable in his voice and in his stage presence. And maybe that’s why the backlash stings a little.

“I don’t have thick skin,” Bridges says of the Observer piece. “It cut me up. But I got over it the next day.” Of course, it’s easy to let that sort of thing roll off your back when you’re sitting on top of the world. Bridges’s debut, Coming Home, is due June 23, and soon after we spoke, he was invited to play the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s induction ceremony on April 18 as the night’s only newcomer. (He was asked to perform in honor of the R&B pioneers the “5” Royales, whose music doesn’t sound all that much older than his.)

“It’s so crazy,” he says, breaking eye contact and slumping into his chair, as if he’s a little embarrassed by it all. “So crazy. Everything is moving so fast.”

And then, in a quick pivot, one that suggests he’s not a complete naif, he says his plan is to keep doing exactly what he’s done all along, the very thing that led him out of the kitchen, into the waiting arms of Columbia Records and SXSW, and onto the big stage at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

“I’m going to keep doing me,” says the very likable Leon Bridges. “The rest will fall into place.”