Although Western novels started losing readers in the sixties, don’t blame the waning interest on Texas writers, who have since provided the flagging genre some of its best moments. Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, the 1986 Pulitzer Prize winner, was followed by Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, which won the National Book Award in 1992. Austin author Philipp Meyer’s Pulitzer finalist The Son, published last year, proved that an inventive young writer can still stake his ambitions on the wide-open plains. And this year, three of Texas’s most experienced and respected chroniclers of the Old West have returned to familiar turf: McMurtry himself in The Last Kind Words Saloon (Liveright Publishing), along with Lonesome Dove teleplay writer Bill Wittliff in The Devil’s Backbone (University of Texas Press) and Fort Worth journalist Jeff Guinn in Glorious (Putnam), the latter two titles introducing anticipated series.

It’s hardly surprising that Texas, with a long-established cult of its own frontier past, would remain an incubator of Western fiction. As codified by Texas literary giants like Walter Prescott Webb and T. R. Fehrenbach, our quasi-religious history has often resembled historical fiction—a triumphalist mythology that a generation of “revisionist” (i.e., factual) historians has largely failed to budge from our collective psyche. Instead, ironically, the task of debunking all those popular misconceptions has fallen to contemporary Western novelists. Historical revisionism, it seems, wears better in cowboy boots; over the past three decades, the nihilistic anti-heroism of McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985) has evolved into Meyer’s more complex but no less morally desolate frontier, where everyone is either a victim or a thief. While the new offerings by Wittliff, McMurtry, and Guinn are considerably less apocalyptic in tone than McCarthy’s and Meyer’s books, they similarly challenge old-school readers with timely meditations on racism, sexism, and even economic inequality.

Screenwriter Wittliff’s ear for dialect is integral to The Devil’s Backbone. The novel is a fictive oral history, the phonetically if not grammatically correct recollections of a narrator known only as “Papa,” who as an adult recites a picaresque tale about his childhood in Central Texas in the 1880’s. Like McCarthy, Wittliff eschews quotation marks, which in concert with the second-generation first-person narrative can result in syntax as baffling as “And I come a’running I said, Papa said.” But readers who master the meta-grammar will find themselves entirely transported to a time and place as lyrically surreal as it can be chillingly real. The most terrifying presence is Papa’s papa, Old Karl, a hard-drinking, sadistic German horse trader who cruelly provokes his long-suffering wife to leave him, launching the prepubescent Papa on a book-length journey to find her.

Wittliff, who is also an accomplished photographer, transforms Papa’s semiliterate vocabulary and run-on sentences into strikingly poetic imagery, such as the portentous reappearance of a three-legged coyote Papa has befriended: “I guess the Stars just dropped down out a’the sky and is a’looking for a place to settle in the World but No . . . coming right out a’the Brush with them Lightning Bugs a’sparkling all round his head like a big o’twinkling Hat a’Lights was my o’Friend Mister Pegleg his self.” Papa’s search leads him into an increasingly numinous world, where animals are often wiser and more humane than humans, a blind infant and an old black woman have oracular powers, and ghostly “Shimmery People” visit his dreams, beckoning him to the denouement at a well-known Hill Country landmark, a snaking limestone ridge called the Devil’s Backbone.

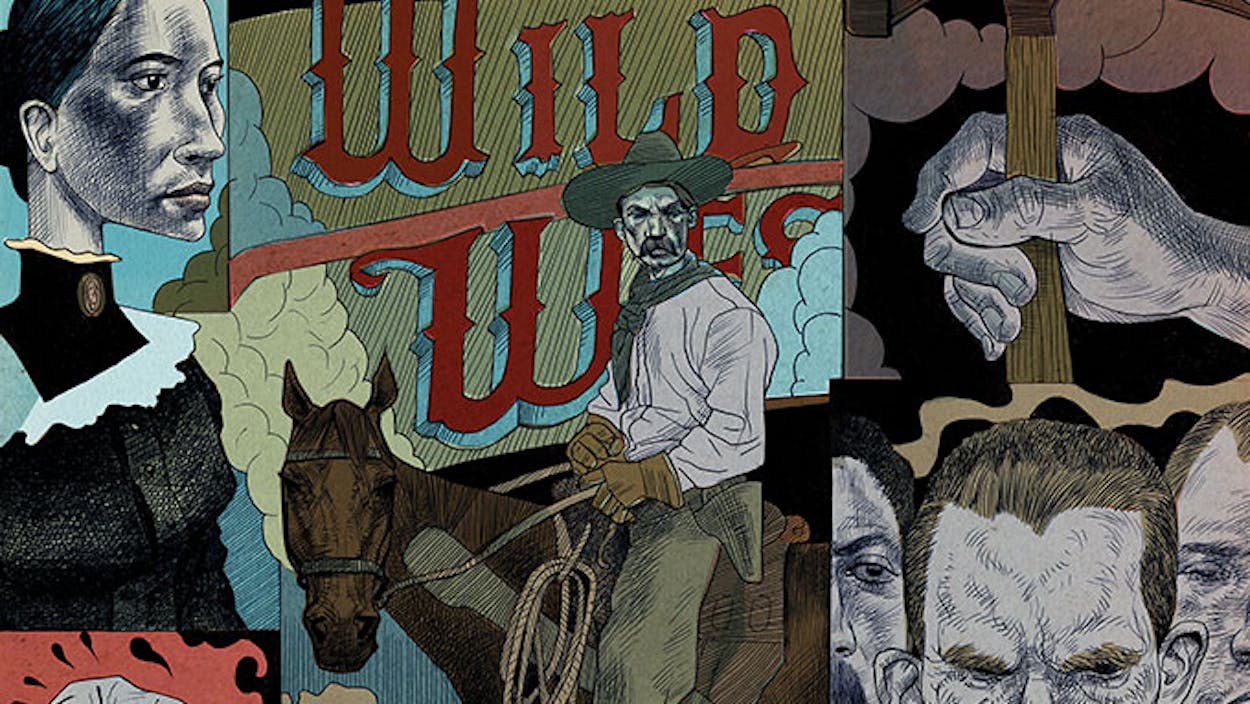

There’s also much of the usual fodder for Western fiction—a misunderstood outlaw, untrustworthy lawmen, horseplay and gunplay—but Papa’s narrative, perfectly complemented by Dallas artist Jack Unruh’s sophisticated yet folkish illustrations, invites us to revisit the Old West with wondering eyes. Equally unexpected is Wittliff’s perspective on the ubiquitous frontier mayhem. Old Karl’s force-of-nature psychopathy is similar to that of such primordial villains as Lonesome Dove’s Blue Duck and Blood Meridian’s monstrous Judge Holden, but with a telling distinction: Old Karl’s violence is almost entirely domestic. With blows and threats, he exacts backbreaking labor from his wife, his sons, and a subsequent concubine, all of whom long to escape but justifiably fear Old Karl’s brutal reprisals. And the real heroes turn out to be a couple of well-drawn women who at great personal risk stand up to the tyrant. Of course, for decades now, spunky, independent spitfires have been a staple of Western fiction, not to mention Western-themed romance novels. But The Devil’s Backbone suggests that we might find a less fanciful and more relevant heroism among the anonymous frontier wives who endured the same discomforts and dangers as their husbands, while also confronting the all-too-deadly perils of spousal abuse.

McMurtry’s reputation as a demythologizer of the Old West precedes him into The Last Kind Words Saloon in much the way that Wyatt Earp’s reputation as a formidable lawman accompanies him into the eponymous bar in fictional Long Grass, Texas, roughly around 1880. More than a dozen Western novels down the road from Lonesome Dove, McMurtry, like Earp, comes across as sharp-eyed, laconic, and pretty well bored with it all. In the preface McMurtry describes this sub-two-hundred-page novella as “a ballad in prose whose characters are afloat in time; their legends and their lives in history rarely match.” And that’s just the historical characters, like the Earp brothers, Doc Holliday, Charles Goodnight, and Buffalo Bill Cody, whose Wild West Show advances the plot by going bust in Denver a quarter century before it did so in fact. Similarly unmoored are fictional characters like peripatetic reporter Nellie Courtwright, who drops in from her starring role in McMurtry’s Telegraph Days, though on this visit she doesn’t witness the climactic shoot-out at the O.K. Corral.

The Last Kind Words Saloon showcases some impressively economical prose: “Caddo Jake snapped awake and looked to the west. ‘Sand,’ he said, and that was all he said.” Unfortunately, McMurtry’s foreboding pith and fungible time line never add up to a galloping plot. The halting, haphazard pace does make a salient point: real history doesn’t unfold in tightly knit chapters leading to an inevitable conclusion. And often the events we now deem historic—like the Earp brothers’ thirty seconds of gunplay in Tombstone—were remembered only because of the random attentions of the media. In McMurtry’s satiric retelling, Earp doesn’t really learn to shoot until Cody casts him as a gunfighter in his Wild West Show; his celebrated cool is often cluelessness, and his survival at the O.K. Corral is as accidental as the gunfight itself.

McMurtry similarly deflates the power struggle that prompted the actual shoot-out, a clash of cultures between cowboys, who were not infrequently outlaws and rustlers, like the Clanton gang, and flawed lawmen, like the Earps, who often were little more than itinerant mercenaries hired by stability-seeking townspeople. As in the real West, the conflict is mooted by big business; Goodnight partners with fictional British investor Lord Ernle (based on Goodnight’s actual Irish financier, stockbroker John George Adair) and plans the sort of mega-ranch that will soon make good bookkeeping and efficient management the most valuable cowboy virtues. But even these prairie moguls come across as less capable than their significant others. Both Goodnight’s wife, Mary, and Ernle’s fictional consort, San Saba (allegedly fathered in a seraglio by the Turkish sultan), shrewdly adapt to events on the ground, while the men in The Last Kind Words Saloon sleepwalk toward their unintended dates with history.

Glorious is the first novel from best-selling nonfiction writer Jeff Guinn, whose previous books include The Last Gunfight: The Real Story of the Shootout at the O.K. Corral—and How It Changed the American West. While Guinn doesn’t display the literary panache of McMurtry or Wittliff, his detailed research and lucid exposition are likely to be more congenial to hard-core Western enthusiasts. But Guinn is no less a revisionist, and his protagonist, Cash McClendon, is no white-hat hero; an orphan who rises from the streets of St. Louis as a union-busting snitch for a thoroughly unprincipled capitalist, Cash has never ridden a horse or shot a gun. After he runs afoul of his employer, he flees to a tiny Arizona boomtown, Glorious, hoping to start anew with an old flame. That frustrated romance is lively but strictly PG, and even when Cash finally succumbs to the flirtations of a whore who doesn’t have a heart of gold, the consummation requires only a single sentence. Instead Guinn’s plot turns quite ably on late-nineteenth-century laissez-faire economics, which provide a pointed contemporary resonance. “Self-interest drives our great land,” Cash is told by his monopolist boss, who won’t hear of reading classes for his workers’ children. “Why would anyone willingly do something for someone else if he himself doesn’t benefit?”

In Arizona, Cash finds it’s much the same; the little people risk everything in hope of a silver strike that will metamorphose their miserable collection of canvas tents and adobe hovels into a real town, while a wealthy rancher, abetted by a corrupt territorial governor, rigs the game to cut them out. “We work hard and we’re honest and still whatever we have can be taken away on a rich man’s whim,” laments Glorious’s struggling sole innkeeper. “I know it happens all the time back east, but it wasn’t supposed to be that way out here.” In Guinn’s tale, the only defense against the predation of the powerful few is the communitarian resolve of the many, a moral lesson that propels the stirring climax—and sends Cash, finally mounted, riding painfully and unsteadily off into the next installment.

Guinn’s story line leads us to the irony at the heart of all three books. The modern West has become the breeding ground of a highly romanticized, lone-gunslinger libertarianism (witness the recent well-armed attempt to make a hero of deadbeat Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, before he was exposed as an unreconstructed bigot). But Western history, and today’s best Western fiction, tells a different story, in which the real heroism is found among the men and women of all races (the three authors take pains to challenge the Old West’s endemic racism) who struggle to build small businesses, stable families, and well-governed communities. When McMurtry’s Charlie Goodnight confesses to his wife that he tracked down and summarily hanged two young horse thieves, Mary angrily insists that he “make this into a proper county, with judges and courts and all that goes with a county. And after the courthouse I want a college, where people can learn their algebra.” (In real life, Charlie did hang those horse thieves, while Mary helped start a Panhandle college.) The gunslingers still enjoy a thriving afterlife in the American imagination, but they passed into history without really hitting much of anything. Instead it was the civilizers like Mary who actually won the West.

- More About:

- Books

- Cowboys

- Larry McMurtry

- Bill Wittliff