The ancient delights of congregating around a crackling fire pit on a chilly night have been enjoyed by humankind for some million or so years. For our Homo erectus ancestors, the flames were a necessity of survival, providing warmth and light and also allowing for the world’s earliest barbecues. Over the millennia, with the advent of roofs and walls and central heat and air and the like, fires have become somewhat less do-or-die for today’s man. In fact, a good fire, once so invaluable, is nowadays mostly taken for granted. But if you’re like me, the primordial pleasure derived from an evening spent with fellow humans gathered around a pit ablaze with glowing embers is something to be prized and appreciated. So let us take a moment to hail the fire pit.

It’s an unproved theory of mine that the flames of fiery fellowship burn brighter in the backyards of Texas than they do in backyards elsewhere, but I’ll admit that this is just a notion borne of the images that come to mind whenever I have the opportunity to stare at a stack of burning logs for a spell. On these occasions, I’ll often find myself momentarily hypnotized by the flickering light. Thoughts of the campfires of early Texans fill my head. Comanche in Palo Duro Canyon, Apache in the Trans-Pecos, Karankawa down on the coast. Spanish conquistadores, Rangers, settlers, and cowboys on unknown plains. The sun has set, and the campfire is lit. Flittering sparks rise in the column of smoke as night falls. Hey, I need another beer.

During the holidays, I found myself in just such a trance. It was at a dinner party at a home in the Tarrytown neighborhood of Central Austin. The hosts had made a fire in one of those small, metal store-bought pits out on the patio, and guests huddled around it as that first real norther blew through. One of the partygoers happened to be a woman I had grown up with, in Temple. As we warmed our innards with wine and our outtards with the fire, she was reminded of a favored high school party spot over on Belton Lake. “The Land,” as it was known, was a piece of lakeside property owned by the family of a schoolmate where a horde of young Wildcats (and even some Belton Tigers) would occasionally gather to revel in our collective youthfulness.

The Land was an excellent proving ground for those first unsupervised fires. And as ZZ Top blared from a pair of six-by-nines wired to reach the rooftop of a friend’s El Camino, we young fools would perform boyish exploits of flame leaping, hot coal juggling, and beer chugging. Amazingly, nobody suffered lasting injury. At least that I can recall. Here’s to the good times!

My pyro history, which is probably not too dissimilar from that of many a Texan, includes other formative blazes. My dad, an attorney by trade, was also a farming and ranching hobbyist and had a small spread outside Temple, in Sparks, that seemed to produce more mesquite than anything else. Mesquite requires lots of clearing, and mesquite clearing requires lots of fire. My dad would douse the enormous heaps of thorny brush with diesel, ignite them, and then leave the raging infernos in the care of my two older brothers and me. These weren’t recreational fires, strictly speaking, but that didn’t stop a young boy from having a good time tending them. Hot and dirty from head to toe, with a shovel in my gloved hands and pride on my face, I would have made a good subject for Norman Rockwell—if Norman Rockwell had ever dared capture such a hellish vignette.

As I remember it, though, the real fireside fun of my youth occurred during annual summertime treks to Padre Island where my dad would host a large bonfire at the same spot on the north end of the seawall every year. These were open-invitation affairs, and all were welcome. He seemed to relish these fires with a particular gusto, and he would advertise them to friends and confused youngsters with promises of roasted hot dogs and marshmallows and the “singing of songs of World War I and II.” We’d spend the day collecting all the burnable driftwood we could find, dig a pit, and then he’d do his thing. I don’t recall any actual war songs being sung, but then I would have been fast asleep by the time enough gin and tonics had been consumed to properly loosen up the vocal cords. Thinking back now, I really have only vague memories of long-lost childhood playmates, sandy wieners, and overdone marshmallows. My clear memories are of my dad’s enthusiasm for gathering friends around a fire. And, like the smell of smoke, they’ve stuck with me.

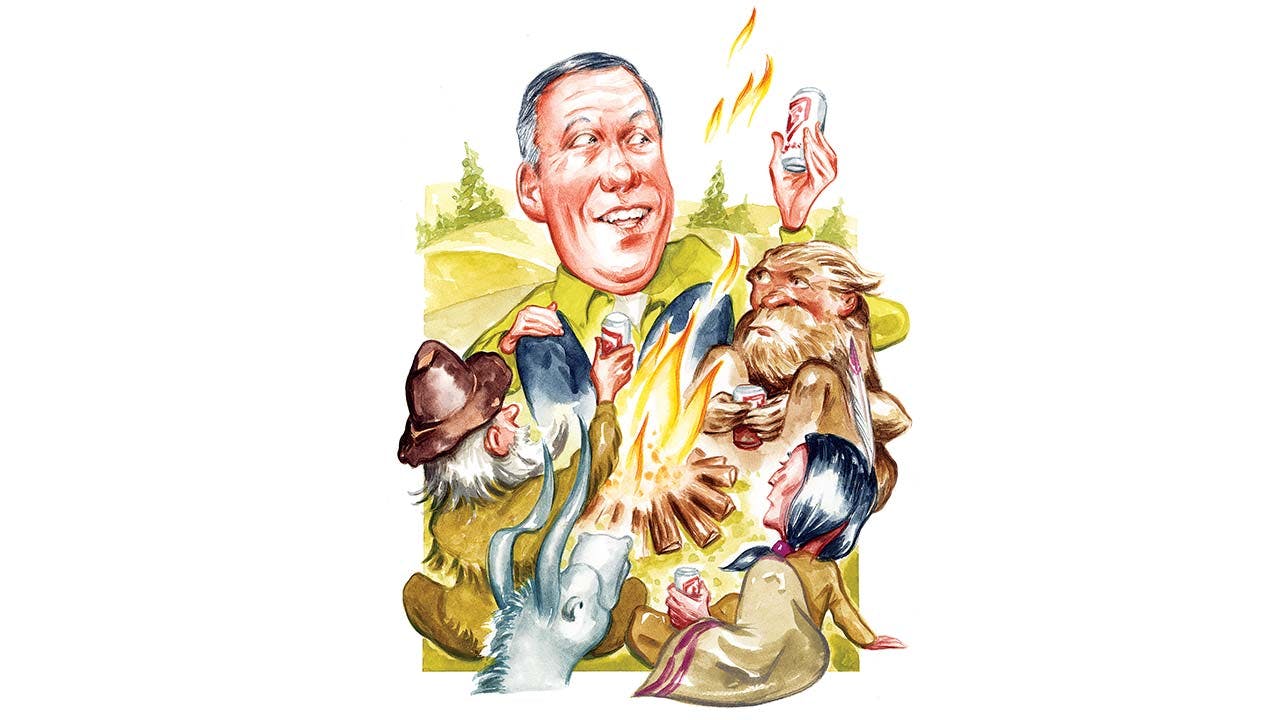

The next time you find yourself in the proximity of a fire pit, whether it’s a citified backyard blaze, a campfire out in the country, or a big beach bonfire, do yourself a favor and take time to appreciate the simple pleasures that such communal fires provide. Tell tall tales, enjoy libations, and forge friendships. And remember to raise a glass (or can or bottle) to the cavemen, to the Native Americans, to the frontiersmen, and to the cowboys for whom similar flames were once so much more fundamental. Think of the fires of your own youth. And think of the high schoolers still out there (a short prayer, if you have it in you, wouldn’t hurt). That’s what I’m going to do. And I’ll raise another one for the memory of my dad, from whom I inherited an enjoyment of life’s humbler gifts. Let’s all hail the fire pit.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: Despite having violated the team curfew while out tying one on the night before 1967’s Super Bowl I, Green Bay Packers wide receiver and Overton native Max McGee, after making an incredible one-handed grab of a Bart Starr pass and taking it all the way for a touchdown, scored the first-ever Super Bowl points. The Packers bested the Kansas City Chiefs 35–10. And Gregarious McGee is remembered for saying “When it’s third-and-ten, you can take the milk drinkers and I’ll take the whiskey drinkers every time.”