In 1946 four brutal crimes occurred in less than three months in Texarkana. Three were violent attacks on young people parked on lovers’ lanes on the Texas side of town; the fourth was the shooting of a middle-aged couple in their rural farmhouse on the Arkansas side. At the end of the spree, three people had been seriously wounded and five had been shot dead. The traumatized survivors gave the police little to go on. Fear paralyzed the town. Women of means packed up their clothes and children and checked into downtown’s Hotel Grim when their husbands were away on business. Others rigged Rube Goldbergesque security systems, attaching pots and pans to wire that was strung around their property. People who had never owned guns slept with loaded pistols on both sides of the bed and made pallets on the floor so their children could sleep beside them. Lawmen from Arkansas and Texas and members of the national press overwhelmed the town in pursuit of the assailant, who was dubbed the Phantom Killer by the Texarkana Gazette.

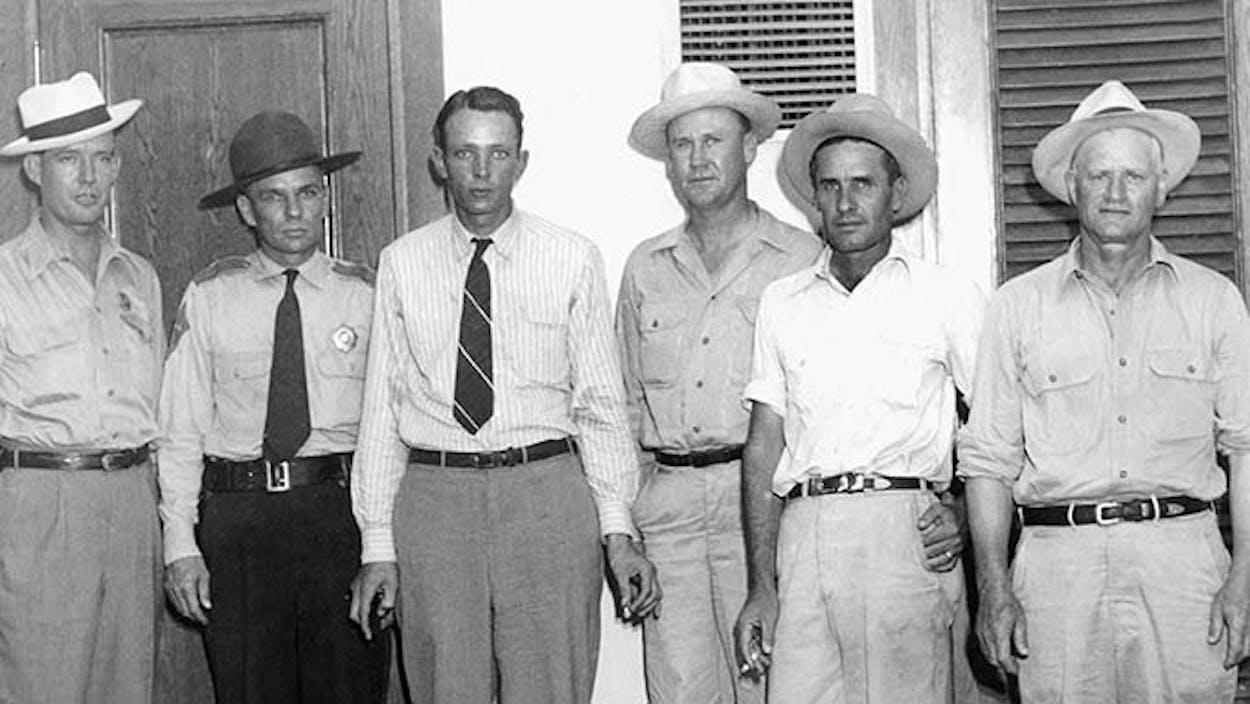

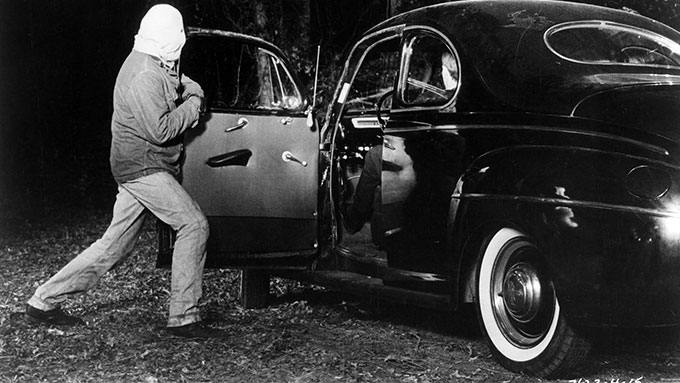

A still from the 1976 film The Town That Dreaded Sundown. (Photograph from American International/Photofest)

A still from the 1976 film The Town That Dreaded Sundown. (Photograph from American International/Photofest)

Decades later, the mayhem has barely lost its hold on the popular imagination, though “imagination” is very much the operative word. A handful of books of wildly varying quality have been written about the case. The Town That Dreaded Sundown, a largely fictionalized movie, was released in 1976. A remake of the same name came out this past October. The famous “Hookman” urban legend—the one that begins with a young couple parked on a lovers’ lane and ends with their discovering a bloody hook on the car’s door handle—is said to have been inspired by the Texarkana murders. (Though there’s no evidence that the Texarkana killer had a hook.) In a state hardly celebrated for its peacefulness, the Texas Department of Public Safety once called the serial killings “the number one unsolved murder case in Texas history.”

Yet for all the attention given to the case, no one was ever convicted of the crimes. “The case cried out for a reliable record to preserve the known facts, dig up new ones, and separate the substantive evidence from the spurious and imaginary,” says James Presley, a Texarkana native whose authoritative examination, The Phantom Killer: Unlocking the Mystery of the Texarkana Serial Murders: A Story of a Town in Terror, was published last month. “Writing this book was like assembling a jigsaw puzzle from scattered small pieces, some of them missing.”

One recent afternoon, I drove around Texarkana with Presley to revisit the four crime scenes. Sixty-eight years ago the sites of the attacks were at the very edges of town. Today, one is in a suburban development, one is a nondescript lot near a handful of commercial buildings, and another is an unremarkable wooded area by a public park. Nothing in any of the Texas locales evokes the horror of a sudden flashlight beam on a pitch-black night and an armed stranger demanding, “Take off your f—ing pants”—the instructions given to Jimmy Hollis, the male victim of the first attack.

Presley seemed less sure of the precise location of the final murder scene, in rural Arkansas. The farmhouse where Virgil Starks was killed and his wife, Katie, was grievously wounded is long gone, but we bumped over the railroad tracks and followed crunchy pea-gravel roads through Arkansas farmland, imagining what it was like for that poor woman to run for help across these dark fields as blood soaked her nightgown. “I’m pretty sure that’s where Max and Charley [Arkansas state troopers Max Tackett and Charley Boyd] spotted that old parked car,” Presley said, pointing toward a clump of woods where an automobile later thought to have been the murderer’s was parked the night of the attack. Had the lawmen not been racing to drop off expense reports at headquarters, they might have checked out the suspicious car, since this stretch of road was a known moonshine drop-off point. “They always regretted not stopping to investigate,” he said.

A year after the shootings, Presley was hired as a seventeen-year-old cub reporter at the Gazette, working with journalists who had covered the killings. But he had an even closer connection to the case: his uncle Bill Presley was the sheriff of Bowie County, where three of the crimes had taken place. “I recall my father saying during that summer of 1946, ‘I saw Bill today, and he said we could relax now. They’ve caught the guy who did it. He’s an ex-convict. But don’t say anything about it to anyone.’ ” The man his uncle was talking about was Youell Swinney, a local criminal who went to prison in 1947 for auto theft and whom many believe was the killer. Even at the age of sixteen, James Presley had a piece of the inside story.

A reprint of the May 4, 1946 Texarkana Gazette. (Photograph from the Tillman Johnson Collection)

“He died before I started writing this book,” Presley says of his uncle. “But I daresay he and every lawman who worked this case never quit mulling the story over and over in hopes of turning up the hard evidence that could have convicted Swinney of the murders.”

In the intervening years, Presley became a freelance writer tackling quieter subjects, but he maintained his fascination with the case. In 1971 he wrote an eight-part story for the Gazette on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the events. But for decades he resisted writing the definitive book on the subject. “Publishers just aren’t interested in crime stories that have no official solution,” he says.

What finally changed his mind was a 2001 visit from a crew filming an episode of the Learning Channel show Mostly True Stories: Urban Legends Revealed. Standing in the mossy Woodlawn Cemetery, where one victim, Betty Jo Booker, is buried, Presley, the episode’s expert talking head, watched as a man who was with Booker the night of her murder was interviewed. But as he headed for his car afterward, he noticed that the cameras continued to roll as the crew interviewed a tall, paunchy bystander who seemed to be a cemetery groundskeeper. Curious, Presley returned to hear what the man had to say. Relishing his moment of fame, the man told a preposterous story of how local law enforcement kept the killer’s identity secret even though he knew for a fact they had fingerprints.

Presley approached the crew after the man returned to his rake and spade. “Everything he told you is completely false,” he said.

“We know,” replied the producer. “That’s why our show is called Mostly True Stories.”

Appalled at the “news” media’s liberties with the facts, Presley set out to write the authoritative work on the subject. A historian by training—he has a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin—Presley is an indefatigable researcher who is undaunted by aging microfilm, fragile cassette tapes, and dusty old courthouse records. “I was lucky,” he says. “Serendipity, and a great research network, paved the way. There were personal interviews with a range of people, from neighborhood witnesses to well-known psychiatric experts, official records others hadn’t consulted, personal archives, and libraries. Thank God for the Internet—and the telephone! I made hundreds of cold calls. I learned more about serial killers—in general and this one in particular—and their psychology than I’d ever dreamed of knowing. It’s fair to say that I—and the reader of the book—now know more about the Phantom murders and the subsequent investigation than any single lawman who worked on the case.” In fact, Presley’s book makes as convincing an argument as anyone is ever likely to make that Swinney was the killer.

Presley at his home office in Texarkana on October 28, 2014. (Photograph by LeAnn Mueller)

As it happens, Presley wasn’t the only person in my car who had a personal connection to the killings. I was born and raised in Texarkana, and my father, J. Q. Mahaffey, was the editor of the Gazette when the murders occurred—and the man, incidentally, who hired Presley in 1947. I was one year old when the killer struck, so I don’t have any memories of the terror that engulfed the town. If the crimes were ever a topic of discussion around my house, it was only my father expressing his frustration with a national press that seemed intent on forever branding his beloved town as a murder capital. “Still alive, J.Q.?” his editor friends in the East would joke when they called him.

I’ve always remembered the Texarkana of the forties and fifties as a Norman Rockwellian place. The pre-World War II suburb where we lived was the clichéd neighborhood of unlocked doors, homemade Halloween treats, vacant-lot baseball, and chinaberry fights.

But as I looked through Presley’s materials, memories of a very different Texarkana rose to the surface. I was reminded of how the drinking-age enforcement on the Arkansas side of town was notoriously lax. A tired carhop at Lacy’s Drive-in who served beer to my teenage brother and his friends brought a beer for me too; I was eleven. I remembered overhearing talk of drunken brawls at Chaylor’s Starlight Club, and we all giggled about who would put “We Give S&H Green Stamps” signs on the three brothels that lined West Fourth Street.

Some people called Texarkana “Little Chicago,” because its location as a railroad hub brought great performers and famous politicians. But the rails also brought drifters and criminally inclined strangers. The state line that famously cuts through the center of the massive United States Post Office and Courthouse also provoked fierce high school football rivalries and created deep divisions that made law enforcement complicated and inefficient.

Perhaps because a strain of darkness has always crisscrossed State Line Avenue, Texarkana hasn’t tried to hide its most notorious episode the way you’d imagine many a chamber of commerce would. Nearly every Halloween, the city shows The Town That Dreaded Sundown at Spring Lake Park, where one of the murders took place. Next month, Northridge Country Club will hold the eleventh annual Phantom Ball, benefiting a local charity.

During my visit to Texarkana to see Presley, I decided to stop by Spring Lake Park, which I remember as a place to feed ducks, attend Bible school picnics, and play miniature golf. It even had a skating rink, where I learned to skate backward with lean, slithery-hipped older guys who sported Brylcreemed ducktails and Elvis sneers. On this September afternoon, I sat on a bench watching little boys in Bible verse T-shirts fishing with their dads, whose own T-shirts signaled their affiliation with the Christian Brotherhood of Outdoorsmen.

Suddenly, I remembered that the scariest episode of my own teenage years had happened only a few feet from where I sat. In the decade after the Phantom murders, my older brother’s generation generally avoided the secluded lovers’ lanes, opting instead for the security of drive-in movies. But by the time my friends and I were driving, Phantom lore had faded a bit and we gravitated back to the park.

One dark and very cold December night, after a passionate evening of hand-holding at the movies, my crush of the week and I cruised slowly through the park and then stopped the car by the lake, though we kept the heater and the radio running. “Parking,” as it was known then, was an opportunity for talking privately, a much desired commodity in a small town where everyone knew your business. One always hoped, though, that the moonlight and the song on the radio (“One in a Million,” by the Platters) might inspire something beyond a discussion of the Cold War. But just as the conversation that night finally gave way to serious kissing, the heater and radio exhausted the battery of my date’s grandmother’s ’56 Buick.

The heat (both kinds) quickly gave way to chilly panic. My date’s home was New Boston, a small town 20 miles away. After some quick conferral, we agreed that he should lock me in the car and hitchhike down Texas Boulevard to his grandmother’s house about three miles away to fetch the truck he’d come to town in.

No sooner had he sprinted away toward the lights of town than I realized the horror of my situation. The half-remembered Phantom stories returned full force. I was alone in a car on a dark night in the park where a pair of teenagers were murdered in 1946 by someone who, as far as anyone knew, might still be at large. I didn’t know what to do. I considered bolting from the car, but I had on high-heeled shoes. There were no good options.

After the longest 45 minutes of my life, headlights appeared. My date had returned, and I, who had scarcely driven a car before that evening, steered his grandmother’s Buick out of the park as he pushed it with his truck all the way to the Rose Oil service station. Then he drove me home.

My parents, exhausted by my brother’s high school escapades, tended toward benign neglect with me. They were asleep when I returned and didn’t ask about my missed curfew when they woke up the next morning. And I certainly didn’t volunteer any information.

Like Presley, I’ve waited until everyone is dead to tell my story. In 1946 it might have had a different ending.