On May 22, thirty pianists from thirteen different countries, ranging in age from nineteen to thirty, will gather at a hotel ballroom in downtown Fort Worth for a drawing of names—an alternately fussy and homespun tradition that will establish the performance schedule for the fourteenth edition of the quadrennial Van Cliburn International Piano Competition.

Two days later, the recitals and concerts will commence at Bass Performance Hall before a thirteen-member jury. The competition, which combines a little bit of American Idol and a whole lot of Liszt and Rachmaninoff, will cycle through three rounds and culminate on June 9 with the awarding of the victory medals.

Yet this year’s Cliburn will be different from the previous editions in one critical aspect: The competition’s namesake, the concert pianist Van Cliburn, passed away in February from advanced stage bone cancer.

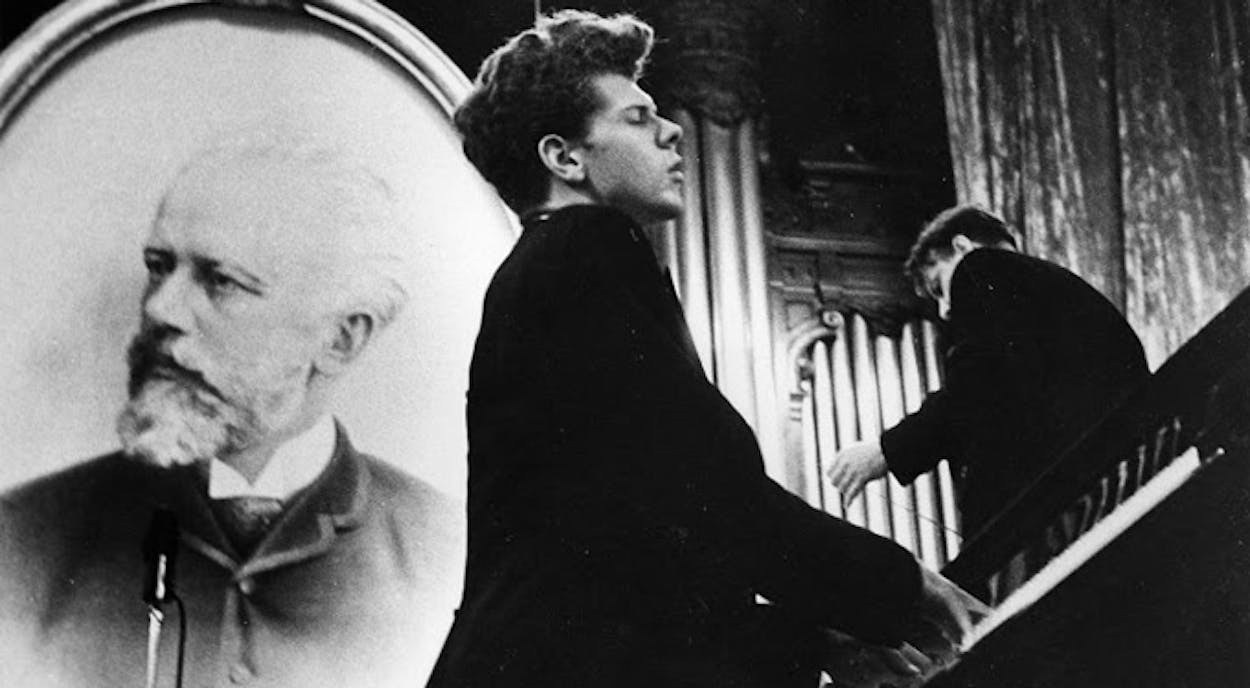

His death came as the Cliburn—which was founded in 1962 to honor Cliburn’s 1958 victory at the Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow—finds itself at a crossroads. In recent years, other piano competitions have eclipsed it, and some suggest that such events in general have outlived their usefulness, especially in an age of reality television competitions, when audiences, rather than elite judges, often decide which performers rise to the top.

The question now is: Can the Cliburn survive without Van Cliburn?

“I think it may have coasted too long on the founder’s name and failed to keep up with global developments,” said Norman Lebrecht, the sharp-penned author of a number of books on classical music. “The piano competition as a spectacle was turned around by the last International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 2011, where every stage was viewable online and Daniil Trifonov emerged as a world star. Nothing at the Cliburn has come close to such excitement in many years.”

The Cliburn has, in fact, began streaming audio of the competition online in 1997, and in 2009 offered extensive online video coverage of performances and rehearsals. The 2011 Tchaikovsky, however, upped the ante, with such innovations as four simultaneous video streams and audience voting.

The famously courtly Cliburn was never involved in the operation or judging of the competition, but he was a regular fixture at performances and could often be spied enveloping contestants in bear hugs after an especially grueling round. His presence lent star power to an event that, in its heyday in the sixties and seventies, was one of the world’s most prestigious piano competitions.

Yet for at least the past decade, criticisms have dogged the Cliburn. One common complaint is that few widely embraced performers have emerged from it.“The only winner of the competition who has become a legendary figure is Radu Lupu,” said Scott Cantrell, the classical music critic for the Dallas Morning News, referring to the Grammy-winning, Romanian-born pianist, who won the competition in 1966. “Whether this kind of gladiatorial situation is an ideal way for identifying significant musicians is a real question.”

Lebrecht has asserted that many piano competitions, including the Cliburn, are too insular and possibly indulge in favoritism. At least two of the judges on this year’s jury have current or former students competing. Cliburn officials counter that if a judge attempted to vote for his or her own student the vote would be automatically nullified.

Lebrecht suggested that one solution might be to allow online audience voting to factor into the judges’ decision. “The days of smoke-filled rooms are over. If the competition is to survive, walls need to be broken down.”

Then there is the series of high-profile turnovers that have beset the Van Cliburn Foundation, the organization that oversees the competition. Following the 2009 edition, longtime president and CEO Richard Rodzinski retired in order to become General Director of the Tchaikovsky, which he is widely credited with revitalizing. Rodzinski’s replacement, David Worters, left in 2011, after just six months on the job. The longtime chair of the foundation’s board, Alann Sampson, then became interim president until she abruptly resigned last fall. Whether these changes are signs of a larger problem remains unknown—no one involved has been willing to discuss the matter on the record.

In a recent interview, Jacques Marquis, who was named president of the foundation in March, steered the conversation away from questions about organizational in-fighting. “Talking about management is not an option,” he said.

Marquis does, though, plan to expand the Cliburn’s online presence to include more profiles of competitors and behind-the-scenes featurettes. And this year, for the first time, audience members at the performances will be encouraged to use their mobile phones and other devices to contribute votes to the webcast tally—which was itself introduced in 2005. (None of this, however, impacts the final jury decision.)

As for the challenge of mounting this year’s Cliburn without its namesake and guiding spirit, Marquis said he is trying to strike a careful balance. A series of tributes to Cliburn will take place during the event, but Marquis doesn’t want the proceedings to turn into an extended memorial service. Or, for that matter, to suggest that the Cliburn competition doesn’t have a long future ahead of it.

“At the awards ceremony we will give the prizes and then we go on. Because carrying Van’s vision forward means moving the vision along.”