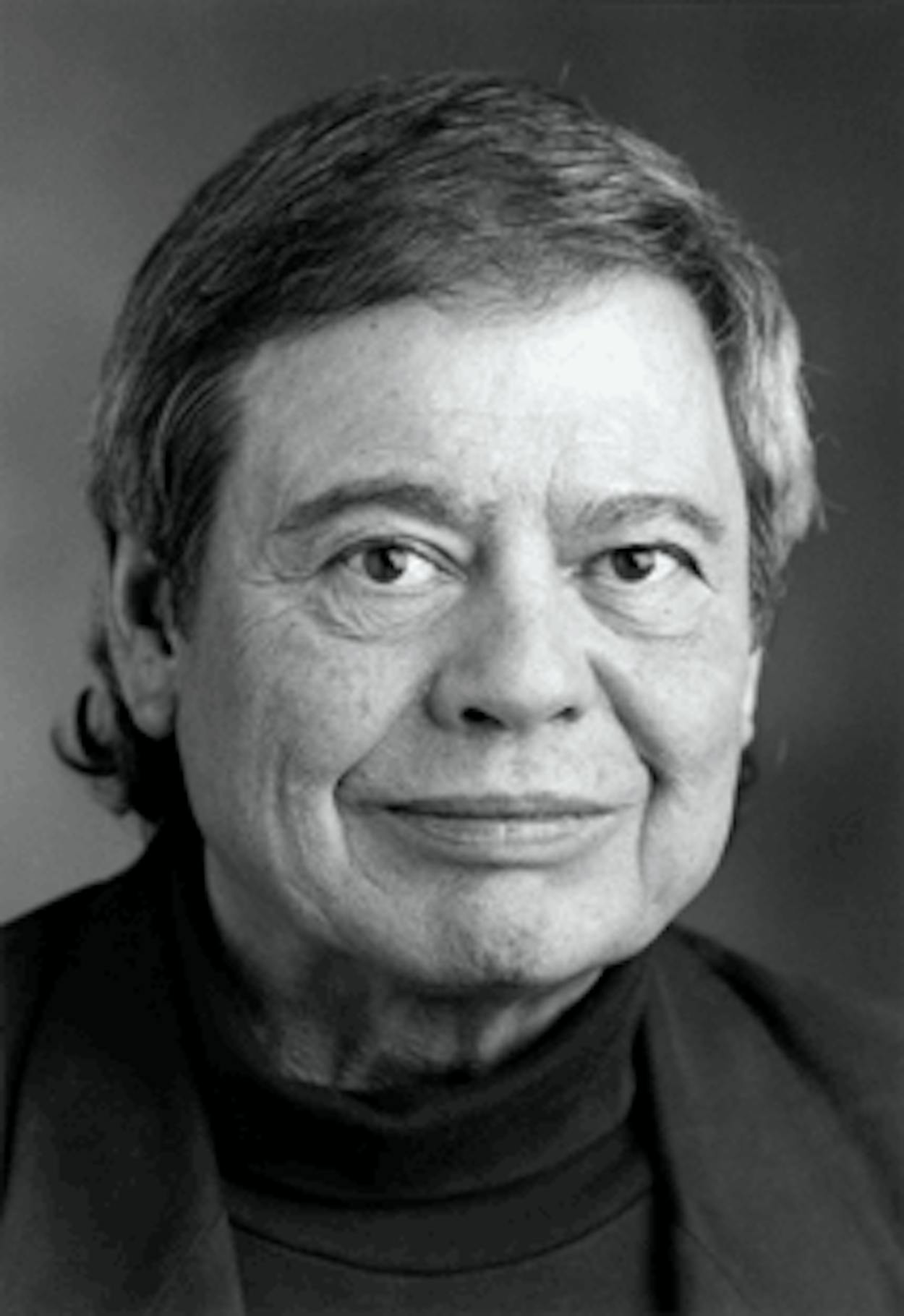

John Graves is not a just a writer—he’s a character—an 89-year-old Emerson-quoting, city-hating kind of man. When senior editor Gary Cartwright recently visited Graves’s ranch, outside Glen Rose, the two talked about the author’s past—chasing bulls in Spain, fighting in the South Pacific, raising cattle and children—and the state he calls home. Through it all, Graves has lived by the honesty of the written word and the land around him. Here’s the story behind the story.

You’ve known John Graves for about thirty years. Did that make it harder or easier to write about him? Why?

Easier, because John is so open, so honest and articulate. I knew going in that I‘d get straight answers and tried to phrase my questions in broad terms so that it would be more like a dialogue than a conventional interview. John is an old hand at talking about himself, of course, and made me comfortable in my job of getting to his core.

Why did you want to write about Graves now?

There were two primary reasons. His great book Goodbye to a River was published fifty years ago, and John is about to celebrate his ninetieth birthday. It seemed like the perfect time to revisit our long friendship.

How did you go about choosing which details to include from his past? And those from his life today?

I concentrated on what was happening now, as opposed to his long and colorful history, which has been written about extensively. Of course, it was necessary to fill in some of his past and to review it again in light of today’s circumstances. I had read a lot of his work—and the work of others who had known him and written about him—so there were areas that I particularly wanted to visit again. Mainly, I wanted to know what he thought about Texas today.

How much time did you spend at Graves’s ranch, Hard Scrabble?

I arrived late one morning, spent the afternoon and evening with John and Jane, slept over in one of their upstairs bedrooms, and talked to him again over breakfast. I was at Hard Scrabble about 24 hours.

There’s a real sense of place in this article—from Graves’s goat pen to the sleepy towns that you pass as you make your journey home. Did you know from the beginning that the story would function in such a way?

Yes, reading John Graves made me aware of how important it is to capture the essence of the place, the small details that make up the whole. In a story like this, I more or less follow my instincts, but I always come prepared for whatever might fall my way.

Do you enjoy writing profiles? How different are they from other kinds of stories you typically write?

It depends a lot on the subject. Profiling John Graves wasn’t that much of a challenge because there was so much background available. I have found that in writing profiles, the more you can learn about a person in advance of the first meeting, the better things turn out. I like to start with a ton of information at my disposal, then look for anything new during the course of talking to the subject.

What was the most difficult thing about interviewing Graves?

John is hard of hearing, so there were times when I had to shout. Also, both of us are old and at times we both lost the train of thought. We laughed about our old age, of course, and it became part of the story, two old farts trying to remember what they had already covered.

Graves is such a larger-than-life character who is passionate about the simple things—land, home, family, and nature. Is he an anomaly?

In an organic way, John is almost abnormally normal. He is both bigger than life and the very essence of life. Which I guess would qualify him as an anomaly.

How do you feel about the Texas we are creating? Do you find it as hard to love as Graves says he does?

Yes, I am often embarrassed to be a Texan. Some of the right-wing lunatics who dominate this state have twisted politics and society into high satire. Like John, I try to keep my sense of humor as a primary defense against going mad.