One afternoon in late May, I entered NorthPark Center, a sprawling, minimalist white-brick shopping mall that sits five miles north of downtown Dallas. I wandered the halls, staring at the shoppers: cosmopolitan habitués whose names populate the society columns in bold print, trendy twentysomething stylistas in stunning high heels, teenage boys in backward baseball caps and shorts that fell below their knees, young suburban moms in yoga pants pushing strollers, and gay men dressed in fashionably shrunken suits. I watched retirees walking at a snail’s pace so as not to spill the coffee that they had just bought at Starbucks, and I watched a tattooed couple holding hands and wearing their pants so low on their hips that I could see their butt cracks.

All in all, it was just another day at what is often called Dallas’s Central Park, where you can find a demographic sampling of every ethnic group and subculture in the city, all of whom come to shop the 193 stores, dine at the 38 restaurants, or watch a movie in one of the 15 theaters.

Then, as I turned into the mall’s “luxury wing”—with its pricey boutiques like Burberry, Tory Burch, Ralph Lauren, Valentino, Bottega Veneta, and Tiffany—I spied the woman I had come to meet. She was wearing Chanel sunglasses, a blue silk blouse, a pair of AG jeans, and strappy black sandals. It was Amy Vanderoef, a forty-year-old former Miss Connecticut who had moved to Dallas in 2004 to host a local television talk show. According to a NorthPark spokesperson, Amy used her NorthPark valet parking card more than one hundred times in 2014, making her one of the mall’s most frequent customers.

“Actually, I think it was more like a hundred and thirty times, considering I come here about three times a week,” said Amy, pulling off her sunglasses with one hand and shaking my hand with the other. We were standing in front of Neiman Marcus—the most profitable Neiman Marcus of their 41 stores around the country. It was bathed in soft recessed lighting. “Boy, do I need to see Jeff,” she said cheerfully, referring to her Neiman’s cosmetics salesman who specializes in Armani products. “That man has saved my face. But I need some coffee.”

She headed down another wing of the mall, cruising by the Gucci boutique (which was displaying a $30,000 crocodile purse just in from its Italian factory), the Versace boutique (featuring a very tiny $7,425 snakeskin dress on one of its mannequins), and the Carolina Herrera boutique (which was selling its alligator handbags for a far more reasonable $7,000). She stepped inside Nespresso, a Switzerland-based company that sells $400 espresso makers, and ordered a straight-up cup of coffee that literally cost $5.50.

“Amy!” exclaimed another perfectly put-together woman sitting at the end of the bar. It was Angela Choquette, who works for a Dallas bank, specializing in philanthropic planning. She comes to NorthPark as often as five times a week, sometimes arriving in the morning with her friends to power walk and take in the “eye candy” in the windows and then coming back in the late afternoon or evening to look at more things to buy. She too was dressed casually, in an Abi Ferrin jersey top, skinny camouflage-print jeans, and caged sandals that matched her not-so-casual Gucci bag. For a couple of minutes, the two women swapped gossip about upcoming Memorial Day sales, including one at Roberto Cavalli, an Italian luxury designer. “It’s going to be very, very busy,” said Angela, downing her espresso.

It could well be said that no city loves to shop more than Dallas. Jack Gosnell, a senior vice president of Dallas-based CBRE/UCR, a well-known specialty retail leasing firm, told me that, according to some statistics, the amount of money spent on consumer goods each year in Dallas breaks down to around $12,837 per resident, which is far higher, per capita, than Los Angeles (a resident there spends $9,705 a year) and New York City ($9,411). “And you don’t have to be a genius in real estate to realize that a lot of that money is spent at NorthPark,” Gosnell added.

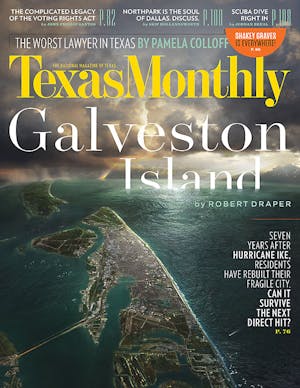

Although every large Texas city has an upscale mall—Austin has the Domain, and Houston has the Galleria—consultants agree that there is no mall like NorthPark, which this month celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. It’s often described as a “shopping museum.” Each year, an estimated 26 million people visit, making it the number one tourist attraction in Dallas. (Please stop for a moment and think about that last sentence. Dallas’s top tourist attraction is a mall.) There are Texans who fly into Dallas’s Love Field and cab over to NorthPark for the day, flying home that night laden with packages. Tourists visiting Dallas from as far away as China have NorthPark scheduled on their itineraries. When my father, a Presbyterian minister who simply hated to shop for anything, spent a few of his retirement years in Dallas, he loved going to NorthPark, “just to see the sights.”

NorthPark doesn’t lure customers with the usual crowd-pleasing (and kid-pacifying) amenities. It has no ice-skating rink, no rubberized play areas for toddlers, and no rock-climbing walls. (Although there is a small turtle-and-duck pond and sloping planters outside Neiman Marcus that little people like to climb up and then slide down.) There are no stores with flashing lights or speakers pumping out high-decibel tunes.

What you will find, surprisingly, is an array of paintings and prints on the walls by such luminaries as Andy Warhol and Frank Stella, and you’ll also be able to walk past fifty or so eye-popping sculptures studding the hallways—among them Jonathan Borofsky’s Five Hammering Men (five 16-foot-tall working-class men hammering away at invisible nails), Mark di Suvero’s Ad Astra (crisscrossing steel beams, two stories high, that are painted bright red), and Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure (a faceless man taking a nap). Scattered around the mall in round planters are as many as 15,000 plants and flowers shipped in from California, Florida, and Germany: orange orchids, yellow Guzmanias, and burgundy Neoregelias. And in the middle of the mall is a peaceful 1.4-acre outdoor garden and lawn, which contains another sculpture, shipped in from Europe, Anish Kapoor’s The World Turned Outside In (a sort of jagged half-moon made of polished stainless steel).

NorthPark is not the most profitable mall in the state: that distinction belongs to Houston’s Galleria, which has 500,000 more square feet in shopping space and does an estimated $1.4 billion in annual sales (compared with NorthPark’s $1.2 billion). But the Galleria isn’t the source of unbridled worship among Houstonians the way NorthPark is among Dallasites. While Houston has Hermann Park and Memorial Park and Austin has Barton Springs, Dallas for many years didn’t have a central outdoor green space. As a result, NorthPark, smack in the heart of Dallas, has become a premier public gathering spot. “When I first moved here,” recalled Amy, “I said to someone, ‘Where do people go when they don’t have anything else to do?’ And she said, ‘Well, they go to NorthPark.’ ”

A single mom, Amy freely admits she is not one of NorthPark’s high spenders. Like thousands of other Dallasites, she often comes just to stroll around and meet friends. And she has a lot of them too. When I asked her to take me on a lap around the first floor, a distance of 2.3 miles, we walked for about thirty seconds before she saw her salesperson at Ted Baker, a London-based clothier. Amy hugged her, promising to return soon to buy a one-piece romper. A minute or two later, she hugged her salesperson at Elie Tahari, a New York-based brand, promising to return soon to look at a dress. We made a right at Nordstrom—“one of my absolute favorite department stores in the world because of their generous return policy,” she said—and headed down another hallway, where she pointed out a fashionable children’s store called Peek (“where I buy all of my son’s clothes”). She showed me La Duni Latin Kitchen and Coffee Studio (“where I usually eat a Trio Salad for lunch”), the Drybar (“where I get my hair blown out every Sunday”), and Spanx (“where, needless to say, I buy Spanx”). Amy did a double take when she saw that Spanx was now selling bathing suits. “Can you believe it?” she said. “There’s always a surprise around every corner.”

NorthPark has all the usual emporiums—Gap, Banana Republic, Urban Outfitters, Macy’s, and Dillard’s—but it’s also loaded with high-end specialty shops. There are at least twenty stores that exclusively sell women’s cosmetics, thirty that sell women’s handbags, and another thirty that sell jewelry, ranging from Hublot, which carries the official watch of the Dallas Cowboys with a price tag of $21,000, to Eiseman Jewels, which displays a pair of blue-diamond earrings that cost a cool $2.75 million.

Tesla Motors has a showroom at NorthPark that features a $70,000 electric car, and Peloton Cycle has a showroom that exhibits $2,000 exercise bikes. The Apple Store is a two-minute walk from the Microsoft Store. And as if that’s not enough, a company called Waterboys, located in the garage next to Nordstrom, will wash and detail your car while you shop, the cost ranging from $25 to $200.

“Do you understand now what I mean when I say this never gets boring?” Amy asked me.

NorthPark is owned by Nancy Nasher, a lawyer, and her husband, David J. Haemisegger, a former banker. If Nasher’s name sounds familiar, it’s because she’s the daughter of Ray and Patsy Nasher, the late real estate developers and famous Dallas art collectors. Ray, the son of a Boston garment manufacturer, graduated from Duke in 1943, where he became a star tennis player. He met a Dallas girl named Patsy Rabinowitz (then a student at Smith College, in Northhampton), and they were married in Dallas, where her parents insisted they live. Ray got into real estate and built a few homes, a few warehouses, and an apartment complex. Then, in the late fifties, when he was in his thirties, he began telling his wife that what he really wanted to do was construct an air-conditioned indoor shopping center on a cotton field in what was then a remote area of North Dallas. Patsy adored the idea. An art lover, she told him that they could also put art in the mall—something no one had ever done before. “Mom and Dad wanted to make NorthPark an aesthetic experience, not just a place to shop,” said Nancy.

It took Ray two years to work out a lease for the land and another two years to get $18 million in loans to build the mall. Before he broke ground, he approached Stanley Marcus, the president and chairman of Neiman Marcus, and asked him to shut down his store in the Preston Center shopping complex a couple of miles away and reopen it in Ray’s soon-to-be-constructed mall. Mr. Stanley said he would do it only if Ray bought out the Preston Center store and helped pay for much of the finish-out of the new store. Ray promptly agreed.

Mr. Stanley was convinced that his elite customers from Dallas’s wealthy Park Cities and Preston Hollow neighborhoods would drive to the new Neiman’s, do their shopping, and then drive straight back to their homes, so he installed only a small entranceway leading out of his store into the rest of the mall. There was no way, he believed, that his clients would deign to darken the doors of the other companies that were signing leases with Ray—such outfits as J. C. Penney, Kinney Shoes, Leeds Ties, Texas State Optical, Olan Mills Portrait Studio, Toy World, Contour Chair Shop, and a women’s pants store called, appropriately enough, Pants Parlour.

It was one of Mr. Stanley’s rare miscalculations. Ray had the mall designed to look like a museum, with clean lines, walls of white brick from East Texas, polished-concrete floors, and plentiful skylights. He told the architects he wanted the complex to look more like “a public square,” because he thought long, straight passages were boring. He wanted the hallways to have benches and sculptures in the middle and to be exactly 38 feet wide, allowing lots of room for customers to walk and mingle. He ordered that the top right corner of every store entrance have a brick with NorthPark’s tree logo. And he declared there would be no NorthPark sign erected next to the adjoining roads. “He hated clutter,” said Nancy. “What he wanted was a big beautiful box where all of the activity took place inside.”

At the opening ceremony, on August 19, 1965, the actor and singer Gordon MacRae, who had starred in several film versions of Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, performed “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning.” The doors swung open, and before the day was over, at least 150,000 people had shown up to see what was inside that big beautiful box. Not only did Neiman Marcus customers pour through the little entranceway to look at the other stores, but customers of Pants Parlour poured into Neiman Marcus to try to understand what all the fuss was about.

It wasn’t long before more-upscale stores were calling, wanting to sign leases. Lord & Taylor eventually arrived. A restaurant called the Magic Pan opened, selling only crepes. “We all raced to NorthPark and said, “Let us eat crepes!’ ” said Jeanne Prejean, a longtime Dallas society writer. “For the first time, we felt so international!” One of the many Dallas teenagers who trooped around the mall on Saturdays was Karen Katz. “It was like walking around a wonderland,” she told me. “I’d go to Neiman Marcus and want to buy everything from a fashion line called Denise Is Here.” After college, Katz entered the executive training program for Foley’s Department Stores, and eventually moved on to Neiman Marcus. Today she is the company’s president and chief executive officer, the first woman to hold the position. Who knows where she’d be if she hadn’t gone to NorthPark?

As the years passed, other developers built their own malls. At one point in the early eighties, there were three within seven miles of NorthPark, all of them filled with fast-food courts and kiosks in the hallways where young salesmen in khaki pants hawked jewel-encrusted purses and toy helicopters that hovered in the air. But Ray and Patsy stuck to their aesthetic vision, adding more sculptures and more high-end stores. “Every Saturday, my father would take the whole family to the center, and we would walk the floors with him while he greeted customers and made sure everything looked just perfect,” said Nancy. “My mom was always stopping to wipe off any dust she saw on the plants.”

Nancy went to Princeton, where she met her future husband, David. When she returned to Dallas after attending Duke law school, she worked for the firm that represented NorthPark, specializing in the leasing agreements, while David went to work for her father, overseeing NorthPark’s financial operations and the NorthPark National Bank (now Comerica Bank), sitting at the northwest corner of the parking lot. In 1995, after Nancy’s mother died of cancer, Ray sold NorthPark to Nancy and David and used some of the proceeds to create the Nasher Sculpture Center, a world-renowned museum of modern art and sculpture in downtown Dallas.

Quiet Nancy, it turned out, was as big a visionary as her parents. Over the next decade, she and David reportedly took out more than $250 million in loans to expand NorthPark, adding a new two-story wing, the outdoor garden, and yes, even a food court—but one designed to look like the restaurant at the Kimbell Art Museum, with custom-designed chairs and banquettes and a glassed-in outdoor area. And she brought in more sculptures—her pride and joy is Ad Astra—and even hired an “art czar” to oversee the collection and add art programming. (Again, please stop for a moment and think about that last sentence. In Dallas there is an art czar for a mall.)

Nancy told me she plans to bring in a hundred new shops over the next three years to take over the leases of stores that have lost their edge. Among those leaving are Foot Locker, Hollister, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Talbots. On their way in are glitzier stores like Longchamp, Canali, John Varvatos, UGG, and Vineyard Vines (which sells things like whimsical ties, not wine).

Obviously, the announcement of new stores has NorthParkaholics in a tizzy. As Amy and I finished our lap around the mall, she saw yet another glamorous blonde—apparently all of Amy’s friends are glamorous—standing by the Neiman Marcus cosmetics counter. It was Alison Wood Solomon, a Dallas native who, as an infant, was pushed around NorthPark in a stroller by her mother and who, years later, pushed her own kids around the mall. “And in a few years, I figure, my daughters will be pushing their children around,” Alison said. “I have no doubt my grandchildren, when they are teenagers, will have the phone number to Neiman Marcus memorized just like I did. I mean, it’s tradition.”

Amy and Alison chatted about clothes, cosmetics, salespeople, and other important issues. Then they hugged and headed off to prowl the hallways. “But what about Jeff, your cosmetics salesman?” I asked Amy. “Didn’t you say you needed something from him?”

She paused.“Oh, I’m okay for now,” she finally said. “Besides, there’s always tomorrow.”