I am in Rudy’s old room in the back, reading, when my mother interrupts me so I can help her move my father from his wheelchair to the bed. Rudy, my older brother, usually comes by every day at 6 a.m. and again on his way home from teaching high school to move him. But I am home from New York for the week, in Ysleta, the neighborhood of my childhood, so the duty has fallen to me.

My mother warns me about my father’s badly healed shoulder. We are to lift him off the wheelchair, then she will pull the wheelchair out from under my father and I’m supposed to get underneath him and lift his deadweight onto the bed. I tighten my grip, and my father yelps, then roars in agony. My mother immediately puts the chair back under him. “Don’t lift by grabbing his waist from behind!”

“Not around the waist! My spine!”

I clearly don’t know what I’m doing. I’m not gentle enough. I may have degrees from fancy schools in the Northeast, but my father doesn’t trust me. He trusts Rudy. I am the son who left at eighteen: ambitious, clueless about life beyond El Paso, ready for an adventure without knowing how it would forever take me away from home.

We try again, and this time I grab his sweatpants. I notice he is wearing plastic underwear. I wonder if I will be able to lift him high enough, if I will drop him as my own back gives way. I don’t want to hurt my father. I hoist him by the pants, my mother lifting and pushing with her shaky hands, and we manage to get him into bed. My mother phones Rudy and informs him that I have helped her move our father. She sounds more hopeful than convinced. I imagine she’ll have to pull and prod my father to the middle of the bed after I leave the room.

My father’s legs are spindly, and his arms are bone-thin. He can sit up in a wheelchair, but he has little strength in his arms and none in his legs. My parents are the same age, 79, but my father’s diabetes has wrecked his body. Here is a man who learned to be a draftsman as he also struggled with English, who built our family’s adobe home—the very house we’re standing in—with my mother, who used his sons as cheap labor to renovate old apartment buildings on the weekends. A proud and tough mexicano. Tonight I stare at my father in the shadows, and he reminds me of a giant fetus in sweatpants. His eyes are closed. Only my mother says thank you as I return to Rudy’s room.

Late that night I am watching the History Channel’s Pawn Stars, when I hear faintly, then loudly, “Bertha! Bertha!” I turn off the TV and walk down the hallway in the darkness. At the door’s threshold, I am greeted by the constant smell of urine from my father’s room, what used to be my parents’ bedroom. My mother sleeps in the next room now. “Bertha! Bertha!” I think of my mother’s recent accident: she fainted in her car at a stop sign on Alameda Avenue, her foot on the brake. Firemen arrived, blocked the car with their fire truck, and readied to break the car’s window. My mother woke up amid the commotion, startled and embarrassed. The fainting spell was probably the result of an irregular heartbeat, coupled with high blood pressure and perennial exhaustion. Since then she’s stopped driving. Now Oscar, my younger brother, takes her to Walmart on the weekends, and Rudy takes her to church.

“Bertha! Bertha!”

I walk into my father’s room, my iPhone’s light on, and ask if I can help.

“I’m stuck. My blankets.”

He looks tiny, shriveled, helplessly tangled up in the blankets. I start pulling them out from under him. I wonder how my mother does this every night, how she ever rests.

“No, this way. To the left!” my father says, half-angrily. As a child, I used to tremble at this tone in his voice. I yank the blankets and free his legs.

“I still can’t turn. I want to turn on my side, toward the edge of the bed.”

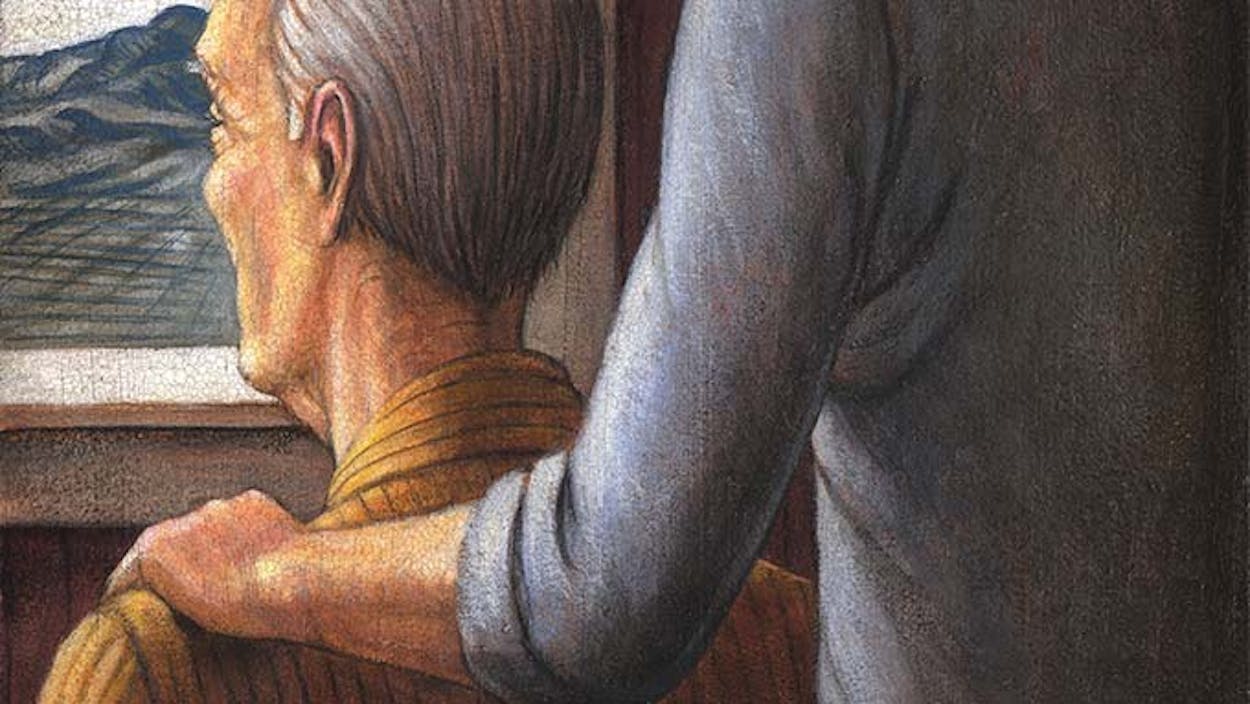

I climb on the bed and start carefully rolling my father onto his right side, pushing his waist from behind and turning his shoulders. I keep slowly rolling him until his fingers grip the gray bar at the edge of the bed. He sighs deeply, finally.

“That’s good. I’m there.”

I cover his thin arms and legs with a light blanket. He is quiet. For once my mother’s sleep is uninterrupted.

On Sunday at six in the morning, I wake up, slip on shorts and running shoes, and drive my mother to church. The sky is gray, and Our Lady of Mount Carmel is about half a mile away, next to the old Ysleta Mission, the heart of this neighborhood before the United States was the United States. It’s the first time this visit that I’ve seen my mother happy. She is dressed in her nicest blouse, emerald green, and black slacks. She has combed her hair stylishly and wears her glasses, which make her look like a friendly librarian. She looks ten years younger than she did yesterday. I pull into the parking lot and say I will pick her up after mass. She asks me to buy $10 worth of menudo from Hamburger Hut on Alameda.

I watch her cross the gravel parking lot. In the breaking dawn, she almost bounces as she walks. She is buoyant, my mother, the most serious of Catholics. The doors to the church are open, and a glow of light spills out from the cinder-block building. Dark layers of clouds gather above, portending a desert thunderstorm. I see my mother dip her hand in the basin of holy water at the entrance, cross her forehead with her fingertips, and enter the foyer, disappearing into the crowd.

The next day, one of the last days before I return to New York, I bring home three chile relleno burritos from La Tapatia. My mother sets my father’s burrito in front of him, wrapped in foil. He slowly, achingly slowly, unwraps it. My mother starts eating hers, and I take huge bites out of mine. My father is still unwrapping, at a slower-than-slow-motion pace, his thick neck and big head hunched forward. My mother doesn’t do things for my father if he can do them himself. He is content at his own speed.

My father holds his mouth open, for seconds, but it seems like minutes. The burrito makes its way upward, gripped by his trembling hands. He is not looking at it. The burrito is half into his mouth, and my father holds it there another second or two before he clamps down with his big jaws.

It is early evening, and the desert breeze skips across the cotton fields and irrigation canals. For years my parents would retire to the front porch in the evenings with a radio and cups of coffee and revel in what they called la hora social, the social hour. They would listen to Mexican crooners like Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante and talk and reminisce about Juárez in the fifties. For hours. I hated it when I was younger, more restless, but my wife, from Boston, always loved it; she said it was like going back in time.

This evening my mother asks if I will help my father into bed again before I drive her to Walmart for groceries, into the busy normalcy beyond their quiet house. I wheel him into his room while my mother makes up the bed with clean sheets, a plastic sheet underneath.

This time I know what to do. I lift him from the front, not the back. I grip his sweatpants and pull him up at an angle that won’t collapse my own back. In one strong move, I hoist him onto the edge of the bed while my mother pulls the wheelchair out. Once he is on the bed, I lift him a few more inches toward the center. My father lies down. I walk around, climb on the bed, grab his waist from underneath, count one-two-three, and my mother pushes, and I pull, and we move him over another two or three inches. Again, one-two-three, until he is where he should be.

I ask my mother if that’s okay.

“Perfect.”

I ask my father if he needs anything, and he asks for his cellphone. I put it under his pillow, as he wants. I turn on the fan above him, open the window as my mother suggests.

As I get ready to leave the room, I hear my father’s clear voice. “Gracias.”

Sergio Troncoso is the author of the novel The Nature of Truth and a resident faculty member of the Yale Writers’ Conference.